On NSA's Subversion of NIST's Algorithm

Of all the revelations from the Snowden leaks, I find the NSA's subversion of the National Institute of Standards's (NIST) random number generator to be particularly disturbing. Our security is only as good as the tools we use to protect it, and compromising a widely used cryptography algorithm makes many Internet communications insecure.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Of all the revelations from the Snowden leaks, I find the NSA's subversion of the National Institute of Standards's (NIST) random number generator to be particularly disturbing. Our security is only as good as the tools we use to protect it, and compromising a widely used cryptography algorithm makes many Internet communications insecure.

Last fall the Snowden leaks revealed the NSA had influenced cryptography specifications as an "exercise in finesse." It wasn't hard to figure out which algorithm had been tampered with. Questions had been raised earlier about Dual EC-DRBG, a "pseudo random bit generator." (A pseudo random bit generator means the algorithm provides a longer string whose properties mathematically approximate those of a shorter random string; uses of the longer string include providing a key for encrypting communications.) There were two problems here. The removal of the compromised algorithm was handled quickly. The more subtle issue was the impact of NSA's compromise. This has undermined NIST's role in developing security and cryptography standards and is likely to have serious long-term effects on global cybersecurity.

This might sound surprising, since NIST's Computer Security Division (CSD) is solely responsible for developing security and cryptographic standards for "non-national security"--- civilian---agencies of the US government. But CSD's success at promulgating strong cryptography through an open consultative process has given rise to standards widely adopted by industry, both domestically and internationally. Now that success is at risk. To understand the current situation, we need to go back several decades.

Who controls cryptography design has been a source of conflict for quite some time. In 1965 Congress put the National Bureau of Standards, now the National Institute of Standards and Technology, in charge of establishing "Federal automatic data processing standards." This law was uncontroversial. Then in 1987 Congress debated whether NIST or NSA would provide security guidance, including cryptographic standards for non-national security agencies. The administration and NSA wanted NSA in charge, but NSA systems, which are designed for national security requirements, do not necessarily fit the needs of the broader public. Industry and the public objected---and won. The Computer Security Act made NIST responsible for developing cryptographic standards for federal civilian agencies. But there was a catch.

NIST was to consult with NSA on the development of cryptographic standards. From the Congressional committee report it is clear Congress intended NIST be in charge. However, in the "consultation" between the agencies, NSA exercised control. NIST's technical reliance on NSA had costs. In the 1990s, NIST adopted a digital signature standard that was NSA's choice, not industry's. Several years later, NIST approval of the Clipper key escrow standard contributed to delay in developing and deploying strong cryptography for the private sector.

This dynamic began to shift in the late 1990s, when NSA started supporting increased security in the public sector. In seeking a replacement for the Data Encryption Standard, NIST ran an open international competition for a new symmetric-key cryptography algorithm. The choice, the Belgian-designed Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), was extensively praised, and much more importantly, has been broadly used. Other successes followed. Because NIST exhibited great care in its technical processes and provided a fair, unbiased process despite strong industry pressures, there was great trust in NIST standards. The benefit was that NIST standards were adopted worldwide. This increased cybersecurity and benefited US industry.

However, as we now know---but apparently even NIST had not---NSA was playing a complex game behind the scenes. While NSA was supporting the AES effort, the agency was also pushing the compromised Dual EC-DRBG. NSA proposed Dual EC-DRBG as a pseudo random bit generator to a private standards body (the American Standards Institute accredited committee for financial tools, subcommittee X9F), where it was approved in 2003. NSA claimed it needed the algorithm, and "encouraged" companies to adopt the standard. In some cases, NSA providing financial incentives for adoption. In December 2013, Reuters reported that NSA had paid RSA Security $10 million to adopt Dual EC-DRBG for its default random bit generator in the widely used BSAFE cryptographic toolkit. With industry and other standards bodies adopting Dual EC-DRBG, in 2006 NIST did so as well. The agency did not deprecate the algorithm even after Microsoft researchers raised concerns in 2007.

(For the mathematically inclined, the problem had two parts. The Dual EC-DRBG algorithm had two unexplained parameters---always troubling for a cryptosystem---while also producing more bits than appeared safe. The Microsoft researchers showed that under certain circumstances, if an attacker knew a mathematical relationship between the parameters, the extra bits being outputted enabled predicting future bits. This was a strong indicator that the algorithm had a trapdoor that would enable anyone who knew the relationship between the parameters to predict Dual EC-DRBG output, thus breaking any system dependent on it. See Matt Green's blog for a fuller explanation.)

When the Snowden leaks indicated a compromised cryptographic specification, it was clear where to look. NIST responded in several ways. The agency promptly removed Dual EC-DRBG from its approved list, and conducted an internal review. NIST also sponsored an external Committee of Visitors (COV) review. The study was a seven-week effort compressed into two teleconferences and a single, day-long meeting. I had hoped to see a long-term, more in depth review of NIST cryptographic efforts, but NIST Director Patrick Gallagher sought a rather quick external review. The charges to the Committee of Visitors were:

Here's what was good about NIST's response:1. Review NIST's current cryptographic standards and guidelines development process and provide feedback on the principles that should drive these efforts, the processes for effectively engaging the cryptographic community and communicating with stakeholders, and NIST ability to fulfill its commitment to technical excellence.

2. Assess NIST cryptographic materials, noting when they adhere to or diverge from those principles and processes.

- The immediate deprecation of Dual EC-DRBG;

- The COV report made numerous useful recommendations, including that standards be developed through open, transparent competitions, that NIST act independently of NSA in evaluating cryptographic standards, and that there be increased NIST expertise in cryptography.

- NIST's internal review noted that:

NIST works closely with the NSA in the development of cryptographic standards. This is done because of the NSA's vast expertise in cryptography and because NIST, under the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 [the follow-on to the 1987 Computer Security Act], is statutorily required to consult with the NSA on standards.

But there was little clarity on what "consult" means. Does consult extend to NSA providing an algorithm for a particular effort, as it did for the Digital Signature Algorithm? Would consult mean that NSA would vet algorithmic security (the role the agency played in the AES competition)? Might consult extend to NIST promoting algorithms supplied by NSA, which was the situation for Dual EC-DRBG?

- Similarly, there has been no government statement about NSA's future role in cryptographic standards setting. A recent National Science Foundation (NSF) committee report in which I participated suggested that "[a] public commitment by the White House — or NSA — that there will be no subversion of NIST standards and process" would help. No such statement has been issued yet, though I understand that one may come soon. Depending on what guarantees such a statement carries, that could be quite useful in restoring trust in the NIST cryptographic standardization and guidelines process.

- Finally there is the issue of funding NIST's Computer Security Division (CSD). While NIST's Committee of Visitors recommended increasing NIST's cryptographic expertise, and Professor Ed Felten recommended increasing CSD's budget, specifics were lacking.

In limiting the scope of the external review, NIST Director Gallagher lost the opportunity to put the cryptographic standards issue in context---and that context is important. For the fundamental problem is that the Computer Security Division lacks the resources to fully fulfill its role. The Computer Security Division is badly underfunded and thus understaffed---and always has been.

While NIST was tasked with developing security and cryptographic standards, it never had a budget commensurate with the task. This was true in 1987, when the Computer Security Act passed. At that time NSA's unclassified computer security program had 300 employees and a budget of $40 million; NIST's computer security operation consisted of sixteen employees with a $1.1 million budget. It was true in the 1990s when, through its technical consulting with NIST, the NSA applied pressure against the deployment of strong cryptography. It remained true after the early 2000s, when industry and other groups lobbied for an increase in funding for NIST's Computer Security Division and Congress increased the division's budget from $10 million to $20 million. Compare that number with NSA's unclassified computer security budget in 1987, worth $63 million in 2002 dollars.

Now NIST's Computer Security Division (CSD) will never be the same size and strength as the cryptographic capabilities at NSA. Nor should it be. But in light of current needs, it is critical that CSD have resources appropriate to its task. The NSF Cybersecurity Ideas Lab report recommended doubling the number of cryptographers at NIST to fifteen. That is a conservative estimate; perhaps the number should be twice that (cybersecurity needs are not going away).

Even with increased staffing in CSD, NIST will never have full expertise to evaluate all potential cryptography standards. In examining the security of proposed cryptographic standards, NIST must leverage outside expertise. Currently it does so through the voluntary participation of academics and industry researchers. Professor Bart Preneel of the Committee of Experts recommended that in instances where the Computer Security Division lacks in-house expertise, NIST should hire consultants. Having additional proficiency will help ensure that slips like Dual EC-DRBG don't recur.

There is a crucial action to take to restore trust in NIST's capabilities: increase CSD's budget. This is an easy step for Congress and the administration to make. Most efforts in cybersecurity face equities on either side: increased information sharing may help in handling current and preventing future attacks, but it puts businesses at risk; regulation of security may improve security but carries threats to innovation. Improving the security of cryptographic standards is an issue where the equities overwhelmingly lie on one side of the equation. By increasing the funding for---and thus capabilities in---NIST's Computer Security Division, Congress can help restore confidence in NIST's cryptographic standards efforts. This is a win for all.

The amount of money is small: tens of millions of dollars annually. The potential gains are huge. Allocating increased funds for CSD will provide the agency with the needed civilian expertise in cryptography. This is a case in which tens of millions of dollars will make a significant difference in cybersecurity; no other investment would have the same bang for the buck. Now that the Committee of Visitors has issued its report, Congress should act. Substantively increase NIST's Computer Security Division's budget. Do so immediately.

***

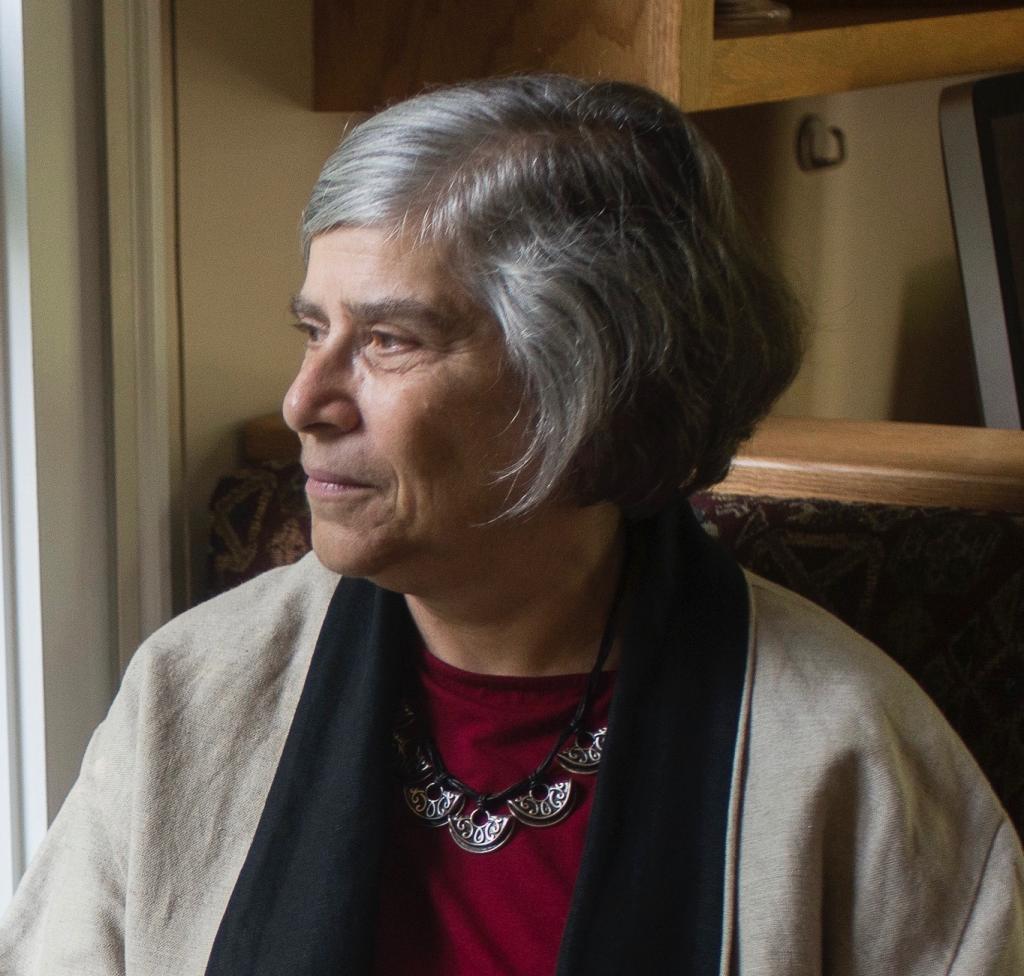

Susan Landau is a Professor of Cybersecurity Policy at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Previously she was a Senior Staff Privacy Analyst at Google and a Distinguished Engineer at Sun Microsystems, and has taught at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and at Wesleyan University. She is the author of Surveillance or Security? The Risks Posed by New Wiretapping Technologies (MIT Press, 2011) and co-author, with Whitfield Diffie, of Privacy on the Line: The Politics of Wiretapping and Encryption (MIT Press, rev. ed. 2007).

.jpg?sfvrsn=8253205e_5)