Russian and Ukrainian Peace Plans Remain a World Apart

A side by side comparison of the two competing visions for the war’s end

After months of diplomatic games between Washington, Moscow, and Kyiv, in which Donald Trump positioned himself as the only leader capable of delivering a swift end to Russia’s war, the American president now seems disillusioned with the Kremlin. Trump couldn’t force Russia even into a short-term ceasefire, much less a lasting peace.

“We get a lot of bullshit thrown at us by Putin,” Trump said during a Cabinet meeting on July 8, a sharper tone than his usual embrace of the Russian dictator. Trump also said he will send more weapons to Ukraine, reversing the policy of Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, who, reportedly unilaterally, halted critical aid deliveries to the country the week prior. Congress, for its part, is close to passing a new Russia sanctions bill, which would punish buyers of Russian energy exports.

To see how little Trump’s appeasement of Moscow has achieved toward ending the war, it’s useful to consider just how far apart the most recent Russian and Ukrainian peace plans are. The Russian peace “memorandum,” presented during the latest round of the U.S.-brokered peace talks in Istanbul, is the first formal, written account of Russia’s terms for peace since 2022, and it is a world apart from its Ukrainian counterpart. The memo reiterates most of the Kremlin’s previously voiced maximalist demands and is widely seen in Ukraine as effectively seeking its capitulation.

The Kremlin “will not respond to pleading or weakness,” said Daniel Fried, former U.S. ambassador to Poland and now a scholar at the Atlantic Council. “The Russians do know how to do diplomacy. They know how to fall off their maximalist positions. But there is no reason for them to do so at the moment, because the West has not put sufficient pressure on the Russians,” Fried added.

What follows is an examination of how the Russian memorandum compares to the Ukrainian peace framework, which Ukraine laid out recently in connection to the negotiations. Examining the two documents, side by side, offers a vivid illustration of why President Trump’s notion that some deal was there for the reaching seems so fanciful.

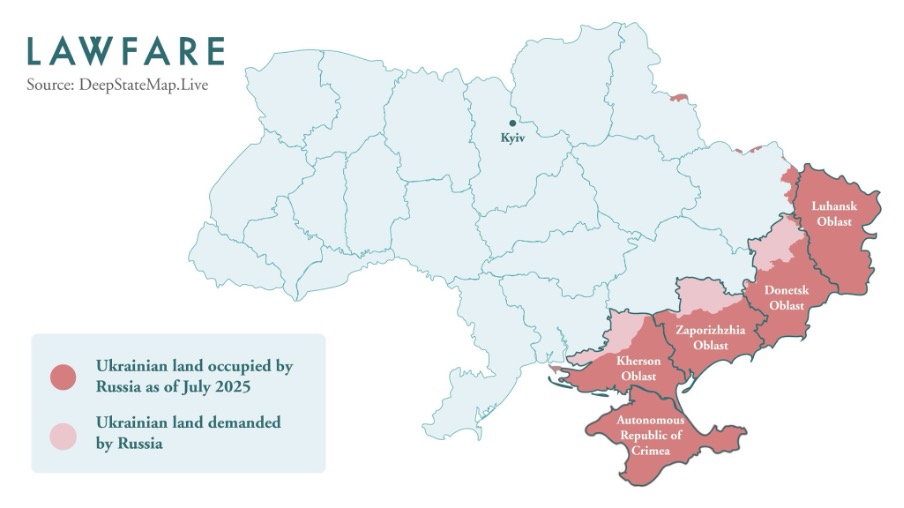

Territory

At the moment, Russia occupies around 20 percent of Ukrainian territory, which is to say about 44,000 square miles. This includes the Crimean peninsula and parts of Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts, which Russia occupied in 2014. The number also includes the territory that Russia occupied since 2022—chunks of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts in the south, as well as more of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in the east. (An oblast is an administrative district.)

The Kremlin has amended its constitution and declared sovereign control over Crimea, as well the entirety of Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, and Luhansk oblasts, even though it never had full control of these territories. To this day, only around 75 percent of those four oblasts are under Russian occupation. In other words, Russia has annexed considerably more territory than it actually controls.

Moscow’s memorandum now demands that Ukrainian forces withdraw from those four regions, voluntarily giving up a chunk of land roughly equal to the size of Taiwan. The Kremlin also demands full international recognition of Russian control of all of that territory, the so-called five regions on which, according to Trump’s special envoy Steve Witkoff, rests the fate of negotiations with Russia.

The Ukrainian government, and even the Trump administration, reject the idea of Ukraine voluntarily giving more land to Russia. “Russia can’t expect to be given territory that they haven’t even conquered yet,” Vice President Vance said in an interview with Fox News, conceding that the Kremlin is asking for “too much.”

The Ukrainian framework acknowledges the fact of Russian control over its territory as a de facto matter.

Although Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said Ukraine will never legally recognize Russian control over any Ukrainian land, he has implicitly conceded that Ukraine can’t return all of its territory militarily. “Perhaps, Ukraine will have to outlive someone in Moscow to achieve all its goals,” Zelenskyy told the Ukrainian Parliament in the fall of 2024.

The Ukrainian framework acknowledges Russian control over its territory as a de facto matter, and, indeed, Ukraine looks increasingly ready to accept temporary Russian control over already-occupied territories. This is a significant concession from Kyiv, considering that for several years the publicly articulated aim of the Ukrainian war effort was liberating all of its territory and returning to the country’s 1991 borders.

But the Ukrainian position insists that Russian territorial gains after its first invasion in 2014 cannot be recognized by the international community. It also says that issues of territory can be discussed only after a ceasefire, at the level of leaders, with the front line being the starting point of negotiations.

In other words, the territorial dispute between the parties boils down to, on the one hand, Ukraine’s demand that a ceasefire comes before territory negotiations and, on the other hand, Russia’s demand for additional territory and international recognition of its gains before a ceasefire can even happen.

To understand how far Russia’s demands are from Ukrainian public opinion, keep in mind that nearly 80 percent of Ukrainians categorically oppose giving up additional Ukrainian territory, according to polling done by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in June 2025.

Security

Moscow’s memorandum demands that Ukraine becomes a neutral state, which, in the Kremlin’s interpretation, means that Ukraine wouldn’t be able to join any military alliances or coalitions or host foreign military infrastructure on its territory. Russia also wants confirmation of Ukraine’s non-nuclear status and a specific ban on the presence of nuclear weapons on Ukrainian territory. Furthermore, Moscow asks for a cap on Ukraine’s military capabilities and capacity, and for a dissolution of “Ukrainian nationalist formations” within the military.

The Russian memo doesn’t explicitly object to Ukraine’s membership in the European Union and to Ukraine having NATO-like bilateral security guarantees from other states.

“You can’t have no external security guarantees and no army,” says Eric Ciaramella, a senior fellow in the Russia and Eurasia program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “If Ukraine isn’t going to get an external security guarantee,” like NATO’s collective defense clause, or a bilateral treaty, “then the security guarantee is the armed forces.”

Ukraine’s document proposes the country retains its ability to pursue membership in the European Union and in NATO, but concedes that membership in the latter will depend on consensus within the alliance. Ukraine also rejects all restrictions on the Armed Forces of Ukraine’s capabilities and on the deployment of foreign troops in Ukraine.

Importantly, Ukraine’s path toward NATO and the EU is enshrined in the country’s constitution. To accept neutrality, the parliament would need to either violate or amend its governing document, which requires a supermajority and would be nearly impossible to achieve in the current political climate.

Sanctions and Reparations

The Kremlin’s memo waives all mutual claims to war-related damages and demands a cancellation of all Ukrainian sanctions against Russia. It also demands the restoration of diplomatic and economic relations between Ukraine and Russia, including gas transit, transportation, and other communications between Russia and the rest of the world that runs through Ukraine.

Ukraine, by contrast, concedes that some sanctions on Russia may be lifted gradually following a ceasefire, but it requests a “snapback” mechanism for their immediate resumption if necessary. Ukraine also demands that Russian sovereign assets, almost $300 billion of which are frozen in European banks, pay for reconstruction or remain frozen until Moscow pays reparations.

Europe froze Russian sovereign assets, which are mainly the foreign currency reserves of Russia’s Central Bank, immediately after Russia’s full-scale invasion. Most of these assets are held by Euroclear, a Belgian central securities depository in Brussels. Ukraine and its allies have called on the European Union to seize those assets and use them to pay for Ukraine’s reconstruction and compensate war victims, but Belgium refused, arguing that Russia will see it as an “act of war.”

Culture

Russia demands that Ukraine make Russian a second state language and ensures “full rights, freedoms, and interests” of the Russian and Russian-speaking population in Ukraine. Russia also demands a ban on the “heroization and propaganda of nazism” and the dissolution of nationalistic parties and groups.

This issue may seem obscure to many Westerners, but it is important to the Kremlin because the supposed protection of Russian-speaking Ukrainians was effectively Russia’s excuse for the war in the first place. The Russians treat the supposed protection of Russian language and culture as a justification for continued interference in and domination of Ukrainian society.

The Ukrainian proposal doesn’t mention linguistic and cultural issues because the Ukrainian government regards the topic as largely a Russian propaganda ploy, which the Kremlin uses to attack Ukrainian identity.

According to the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, a small minority of Ukrainians still speak exclusively Russian at home, and the vast majority of Ukrainians oppose giving Russian any official status. A 2023 poll showed that nearly 85 percent of Ukrainians believed Russian speakers are not oppressed and that their rights are not violated. The number was consistently high across all regions of Ukraine, including the east and the south, where most Russian speakers live. A 2024 poll showed that 66 percent of Ukrainians think the Russian language should be removed from all official communications. Only 3 percent of Ukrainians supported making Russian a second state language, as Moscow demands. Large numbers of native Russian speakers in Ukraine have stopped speaking Russian following the full-scale invasion.

The notion that Ukraine would let Russia define its linguistic or cultural policies is a nonstarter on the Ukrainian side. Ukraine accepting these Russian terms would be “absurd,” and would mean “self-inflicted capitulation,” says Olesia Ostrovska-Liuta, the director general of the National Art and Culture Museum Complex “Mystetskyi Arsenal” and Ukraine’s former deputy minister of culture.

When the Russian Empire, and later the Soviet Union, controlled Ukrainian territory, Moscow went to great lengths to assimilate the native Ukrainian population. Russian authorities heavily censored or outright banned Ukrainian language and culture, while generations of intelligentsia were killed or sent to the Gulag. Today, Moscow insists that Ukraine isn’t a real nation, but an inherent part of Russia.

“The existence of Ukraine as a country that has a completely different historical path, a different language and culture undermines Russia’s neo-imperial project,” Ostrovska-Liuta said.

For the same reason, letting Russia define unacceptable “nationalist” groups that Moscow wants disbanded would open up the floodgates to banning anything even remotely pro-Ukrainian. In the eyes of the Kremlin, “it could be any organization that, for example, uses Ukrainian in its operations,” Ostrovska-Liuta said.

Children and Prisoners

The Kremlin memo makes only one vague reference to humanitarian issues: seeking to “address a range of issues related to the reunification of families and displaced persons.”

In contrast, the issue of missing children features prominently in the Ukrainian document, which calls on Russia to unconditionally return all illegally displaced Ukrainian children, prisoners of war, and civilian hostages as part of “confidence-building measures.”

Ukraine has identified more than 19,500 Ukrainian children that have been abducted by Russian forces and deported into Russia proper during the full-scale war. Russian authorities have illegally taken those children to Russia, Belarus, or occupied Ukrainian territories under the guise of evacuations, and placed them in Russian families or re-education camps where children undergo intense propaganda and even military training. In 2023, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants against Russian President Vladimir Putin and his commissioner for children’s rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, for allegedly illegally deporting Ukrainian children to Russia.

In May, Ukrainian authorities said that at least 8,000 Ukrainian prisoners of war and 2,000 civilian hostages were being held by Russia, though real numbers are likely much higher. More than 60,000 Ukrainians are considered missing, and it’s possible that some of them are in Russian jails.

Interestingly, humanitarian prisoner exchanges have been one of the few areas where the current talks have yielded some fruit. Since the first round of direct talks in Istanbul on May 16, Ukraine and Russia held eight prisoner exchanges, including a major three-day swap dubbed “1000-for-1000,” all of which were the direct result of negotiations. Russia also returned to Ukraine 6,000 bodies of fallen soldiers, though some of them turned out to be Russian combatants.

Ceasefire

Back in March, after a difficult period in U.S.-Ukraine relations that included the Oval Office disaster and Washington halting all military aid and intelligence sharing with Ukraine, Kyiv finally agreed to an immediate, unconditional ceasefire. Yet Russia has effectively rejected it, demanding significant preemptive concessions from Ukraine to make it happen.

In its peace memo, Moscow says it will agree to temporarily stop the fighting in either of two scenarios: if Ukraine fully withdraws from Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, and Luhansk oblasts; or, as a second pathway, if Ukraine stops all movement of its troops, halts its mobilization efforts, begins demobilizing its soldiers, and guarantees that it won’t carry out sabotage activities inside Russia—all while the West stops all military aid and intelligence sharing with Ukraine.

The Russians “feel like there is no pressure to back down,” said Ciaramella from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He thinks the Kremlin is probably betting that it will be harder to restart the war once there is a ceasefire, because there will be some momentum against the fighting.

“Russia knows that it has the most leverage when it’s putting military pressure on

Ukraine,” Ciaramella said. “They feel that the battlefield is going in their direction, time is on their side, so why compromise on anything?”

And that is the key point, when you read the documents side by side: Russia’s demands are meant to be unacceptable to a broad range of Ukrainian society.

President Zelenskyy, in an interview with Newsmax, put it pithily: “Russia wrote a so-called proposal, and they clearly understand: everything written there contradicts the Constitution of Ukraine, the law, international law, and the will of the Ukrainian people.”

He added, “They didn’t write it for us to accept it.”

.jpg?sfvrsn=97d38316_5)