What The Court Didn't Say in <em>Riley</em> May be the Most Important Thing of All

The Supreme Court's unanimous decision in Riley v. California that searching a cell phone requires a warrant is groundbreaking---and is, as everyone says, a great step forward for privacy. The decision is notable for what it does say, including:

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The Supreme Court's unanimous decision in Riley v. California that searching a cell phone requires a warrant is groundbreaking---and is, as everyone says, a great step forward for privacy. The decision is notable for what it does say, including:

The United States asserts that a search of all data stored on a cell phone is "materially indistinguishable" from searches of these sorts of physical items. That is like saying a ride on horseback is materially indistinguishable from a flight to the moon. Both are ways of getting from point A to point B, but little else justifies lumping them together ... Modern cell phones are not just another technological convenience. With all they contain and all they may reveal, they hold for many Americans "the privacies of life."The court's answer to police seeking to search a cell phone? "Get a warrant." This blunt response is a great decision for privacy. To me the decision is even more notable for what it doesn't say. Riley has no discussion regarding expectation of privacy, the two-part test based on whether an individual has sought to keep certain information private and whether society views the individual's expectation of privacy as reasonable. Expectation of privacy underlies decisions in such cases as United States v. Miller and Smith v. Maryland. In Riley, much of the information on the cell phone might have been held by third parties in the "cloud," but the justices did not focus on that issue. In the 2012 Jones GPS decision, five justices (Scalia, Roberts, Kennedy, Thomas, and Sotomayor) ruled that the physical intrusion resulting from placing a GPS tracking device on a car constituted a search; a warrant was generally needed. In a concurrence, Sotomayor presciently observed that, "People disclose the phone numbers that they dial or text to their cellular providers; the URLs that they visit and the e-mail addresses with which they correspond to their Internet service providers; and the books, groceries, and medications they purchase to online retailers. " The concurrence by Alito, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Kagan relied on "expectation of privacy" for the warrant requirement. That concerns me. Phone numbers and urls are not the only digital markers that people disclose. In our increasingly networked world, we leave digital trails everywhere: in E-ZPass data, in Fitbit monitoring information, in the times our homes are heated or cooled. Some is on our phone, and some is in the cloud, where traditionally we've had fewer legal protections. As we trade privacy of intimate information for greater convenience, our society is slowly but surely losing some expectation of privacy. That makes judicial decisions dependent on the second clause of the expectation-of-privacy test, "whether the expectation is reasonable," so fraught. When might the justices decide that, based on societal behavior, we don't have an expectation of privacy in information about what we're reading, for example, simply because Amazon knows what page you're on---and how long you've been there? That would be a dangerous precedent indeed. That is why what the Riley decision didn't say is as important as what it did. In Riley, the court avoided relying on a social construct, expectation of privacy, that may be changing in ways that deeply disrupt society's basic fabric. The justices' reliance on search in deciding a warrant was needed provides important insight to their thinking. For privacy's sake, one hopes this decision is a marker for future ones.

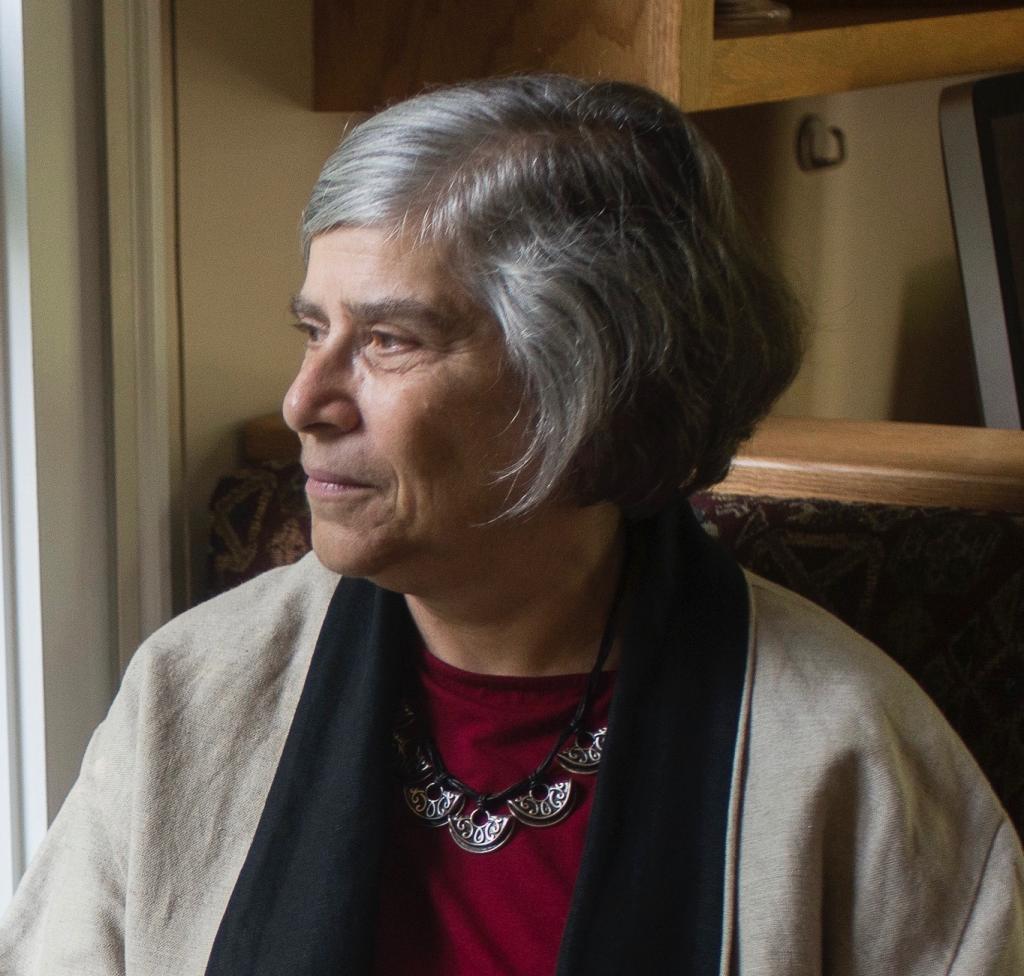

Susan Landau is a Professor of Cybersecurity Policy at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Previously she was a Senior Staff Privacy Analyst at Google and a Distinguished Engineer at Sun Microsystems, and has taught at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and at Wesleyan University. She is the author of Surveillance or Security? The Risks Posed by New Wiretapping Technologies (MIT Press, 2011) and co-author, with Whitfield Diffie, of Privacy on the Line: The Politics of Wiretapping and Encryption (MIT Press, rev. ed. 2007).

.jpg?sfvrsn=d5e57b75_7)