The 2020 Presidential Candidates Stay (Mostly) Quiet on Law Enforcement Independence

Democratic candidates for president have spent relatively little time discussing Justice Department independence on the campaign trail—in contrast to the first post-Watergate presidential election, when Jimmy Carter made rule-of-law reforms a major campaign issue.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

These are hard times for the Justice Department. On Feb. 11, all four Justice Department attorneys prosecuting Trump associate Roger Stone withdrew from the case—and one resigned outright—after the department indicated that it would, following pressure from the president, reduce its recommendation for the length of Stone’s prison sentence. In the following days, reporting indicated that Attorney General William Barr had intervened directly in both the Stone case and in the case of another of the president’s associates sentenced during the course of the Mueller investigation, former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn—not to mention other investigations that directly touch on the president’s interests. Meanwhile, the president tweeted outrage at the department’s decision not to prosecute former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe.

Donald Trump’s abuses over the past week are just the latest manifestation of his long-running campaign against the independence of the Justice Department—a foundational component of the rule of law and the health of American democracy. And yet the Democratic presidential candidates running to challenge Trump in 2020 have largely stayed silent.

There is some debate about the outer limits of the president’s power to control law enforcement as a matter of constitutional law. But for many decades at least—if not much longer—there has been a broad consensus that it is deeply dangerous and therefore wildly inappropriate as a matter of responsible government and political ethics for a president to intervene directly in law enforcement matters in order to protect favored people or punish those who are disfavored. Trump’s alternative vision of direct presidential involvement in Justice Department affairs is to some extent new, but it’s also a throwback to the abuses of Richard Nixon, which contributed to the solidification of this consensus against political interference.

The question of how to curb presidential abuses of power was a focus of the 1976 presidential election, the first following Nixon’s resignation and the revelations of pervasive White House involvement in the Watergate scandal: Throughout his victorious campaign, Democratic candidate Jimmy Carter emphasized themes of ethics and law enforcement independence. In comparison, the Democratic hopefuls seeking the party’s 2020 nomination have been relatively muted on the matter of post-Trump reforms to the Justice Department and the White House’s relationship with it. Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders recently signed a letter calling for Barr’s resignation, but the candidates have overall given Trump’s recent attacks on the Justice Department relatively little airtime.

And this is of a piece with their overall approach to the campaign so far. To get a sense of what the 2020 presidential candidates are advocating in terms of reforms, we reviewed speeches, interviews, policy proposals and responses to questions in primary debates. Some candidates, like Warren and former Vice President Joe Biden, incorporate reform proposals into their platforms; others, like Sanders, rarely if ever address the issue. Yet even those candidates who have placed the greatest weight on rule-of-law issues discuss these reforms and Justice Department independence less than Carter did.

Protecting the independence of the Justice Department is no less important now than it was after Watergate. But unlike in 1976, the 2020 candidates aren’t making the case.

Reforms of the Late 1960s and Early 1970s

The process of reforming the executive branch began well before Watergate. As revelations about executive branch abuses and lawbreaking leaked out during the late 1960s and 1970s—about illegal wiretapping of domestic political opponents, CIA assassination plots, lies to Congress and the public about the war in Indochina, former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s blackmail files, Army surveillance of domestic anti-war protestors, the Watergate burglary and White House “plumbers,” political campaign-related crimes committed by two of President Nixon’s attorneys general, corruption of the Internal Revenue Service and Department of Justice for partisan ends, and many more—various actors in and out of government debated how to better ensure that the executive would follow the law and act in the public interest. Freeing federal law enforcement from politicization and misuse was a key priority.

Congress initially took the lead with reform, because until August 1974 the executive branch was headed by a lawbreaker-in-chief. In 1968, Congress strictly regulated wiretapping in criminal cases. After the Watergate scandal had captured congressional and public attention, Congress in 1973 began to debate far-reaching structural reforms. That spring Congress had learned that Acting FBI Director L. Patrick Gray, whom Nixon had nominated for the permanent job, had provided sensitive information about the FBI’s Watergate investigation to the White House and had destroyed key documents. As one of us (Kent) has discussed previously, this led to a flurry of proposed legislation in the Senate. Democratic Majority Whip Robert Byrd and prominent Democratic Sen. Henry Jackson both introduced bills specifying that the FBI director could be fired by the president only for good cause. Later that year, Sen. Sam Ervin, who headed the Senate’s Watergate committee, introduced a bill to denominate the Justice Department an “independent” department and institute a good cause requirement for presidential firings of the attorney general, deputy attorney general and solicitor general. In early 1974, Sen. Alan Cranston introduced a bill to create an independent special prosecutor office to investigate executive branch lawbreaking. And Sen. Lloyd Bentsen introduced a bill to bar persons who worked recently on presidential campaigns or national political parties from holding the position of attorney general.

None of these far-reaching reforms was adopted at the time. But Congress held extensive hearings on maintaining the independence of law enforcement and adopted important reforms in other areas, including stricter regulations of money in federal election campaigns, regulation of covert actions, a broadened Freedom of Information Act and the Privacy Act of 1974. In addition to Ervin and Cranston, influential Democratic senators such as Birch Bayh, Hubert Humphrey, Edward Kennedy, Edmund Muskie and Abraham Ribicoff were active in these reform efforts.

As the 1976 presidential campaign season arrived, Democrats in Congress advanced other significant pieces of legislation. Access to individual tax returns was strictly limited, to prevent abusive fishing expeditions for tax crimes of political enemies—one of the acts of wrongdoing named in the articles of impeachment drafted against Nixon. Kennedy, Bayh and Byrd introduced a bill to regulate electronic surveillance for foreign intelligence purposes. The Senate passed an extensive Watergate Reorganization and Reform bill—pushed by Ribicoff, Jackson, Muskie and others—which would have created a permanent office of an independent prosecutor for high executive branch crimes and imposed financial disclosure requirements of government officials. Those proposals, with modifications, eventually became law in the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA) and the Ethics in Government Act of 1978.

By the time of the 1976 presidential election cycle, Gerald Ford had held the presidency for only a brief period following Nixon’s resignation. Ford intended to run to hold onto his office, but thanks to his perceived weaknesses as a candidate—caused by his lack of an electoral mandate, the lingering stain of Nixon’s misdeeds, Ford’s own unpopular pardon of Nixon, economic pain deriving from recession and the OPEC oil embargo, and other factors—a large field entered the race for the 1976 Democratic nomination for president. Bayh, Jackson, Bentsen and Byrd announced presidential bids, as did Sen. Frank Church, who led the committee investigating intelligence community abuses; the segregationist governor of Alabama, George Wallace; Gov. Jerry Brown of California; the little-known Gov. Jimmy Carter of Georgia, who would eventually go on to win the nomination and the presidency; and a few other men.

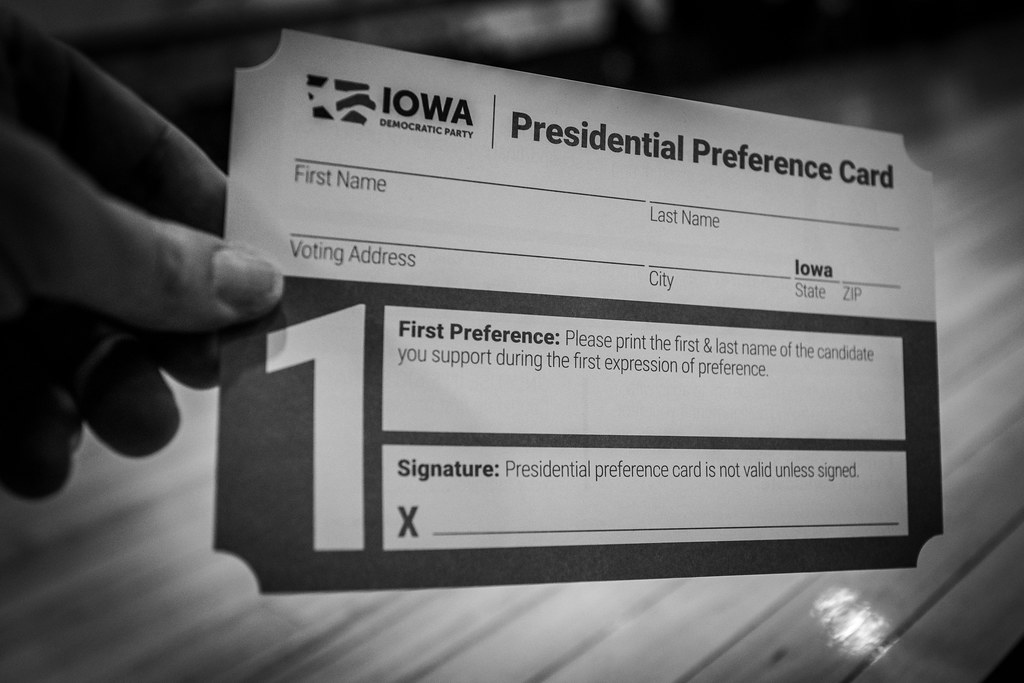

From the beginning of his campaign, Carter built a political message that prominently featured clean government, transparency, ethics, and independence of the Department of Justice from politics. During the campaign in Iowa in January 1976, the Washington Post reported the following:

Former Gov. Jimmy Carter of Georgia today proposed removing the office of Attorney General from the Cabinet and making it an independent office with a term of five to seven years as a means of protecting it from undue political influence. ... Carter made the proposal on a special edition of the television show “Meet the Press” .... Carter proposed the move as a way of shielding the FBI, which is under the Attorney General’s control, in the Justice Department, from political pressure and influence. Carter proposed that the Attorney General be appointed by the President for a term not to coincide with his own and that he could be removed only for malfeasance in office. Removal, he said, would have to be approved by the President and leaders of Congress. Carter said he considered the need to appoint a special prosecutor in the Watergate investigation “an insult” to the Attorney General’s office in that it indicated a lack of faith. He said that under his plan, the Attorney General would function in the independent way of the Watergate special prosecutor.

A major Carter position paper, dubbed by the campaign “Jimmy Carter’s Code of Ethics,” announced that “[t]he Attorney General and all of his or her assistants should be barred from any political activity. He or she should be given the full prerogatives and authority and independence that were recently given to the special prosecutor. The Attorney General should be appointed by the President, with the confirmation of the Senate, and should not be removed except for malfeasance.”

Carter often returned to the theme of the need for a law-abiding Department of Justice independent of politics. He frequently mentioned in speeches the criminal convictions of two Nixon attorneys general (John Mitchell and Richard Kleindienst) and what he called the “prostitution” of the department for political purposes by Nixon. A major campaign profile by the New York Times quoted Carter saying that he aimed “to protect the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the rest of the Justice Department—but particularly the F.B.I.—from the weight of politics.” The 1976 Democratic party platform stated that: "The Attorney General in the next Democratic administration will be an independent, non-political official of the highest integrity. If lawlessness is found at any level, in any branch, immediate and decisive action will be taken to root it out. To that end, we will establish the machinery for appointing an independent Special Prosecutor whenever needed."

While there were surely many other reasons that Carter won besides the attention to Justice Department independence and ethics, Carter and his campaign team clearly believed that these were significant issues with political benefits for him.

None of Carter’s major rivals for the Democratic nomination was as vocal about law enforcement independence from political control. The one who came closest was probably Church, whose presidential campaign arose from his prominent role chairing the Senate committee investigating intelligence agency abuses. In that role and on the campaign trail, Church emphasized the need for the FBI, CIA and other agencies to abide by the law and to refuse to be deployed for partisan ends.

After his election, Carter appointed Griffin Bell as his attorney general. Bell and Carter had long known each other from Georgia, but Bell had never worked for Carter, either in government or on the campaign. As Bell has recounted, “[A]fter taking office [President Carter] kept asking me when we were going to fulfill that promise” to have an independent attorney general with a term “noncoterminous” with that of the president. “Unfortunately, the Office of Legal Counsel [OLC] had, at my request, looked into the proposal ... and reported back that it would be unconstitutional.” Based on conventional legal understandings then and now, OLC was most likely correct.

Although Carter’s most ambitious structural reform for a formally independent attorney general was not pursued further, his administration did make significant progress in protecting the neutrality and independence of law enforcement. Carter and Bell experimented with using a blue-ribbon panel in 1977 to identify candidates for FBI director, though they ultimately looked elsewhere for their nominee. About his experience in the administration, Bell remembers, “I never had any trouble with President Carter about anything. He was very supportive of the Justice Department. He wanted to have it as a neutral department. He had a high respect for the law.” However, Bell recounts that he had “problems ... with his [Carter’s] staff, who thought constantly about politics and about the next election.” To counteract this and related problems, Bell in 1978 announced a policy to strictly limit contacts between the White House and the Department of Justice, and to keep logs of the contacts that did occur pursuant to the policy. Bell also continued important guidelines issued by Ford’s attorney general, Edward Levi, which required factual predicates before any FBI inquiries could be opened—a policy designed to ensure that only legitimate suspicion of criminal conduct or national security threats could call the FBI into action, rather than improper purposes like domestic political intervention, as had happened under Director Hoover.

Carter in 1978 also signed significant “good government” legislation, such as the Inspector General Act, FISA and the Civil Service Reform Act. That same year, he signed the Ethics in Government Act, which created the independent counsel mechanism, as well as mandating other reforms, such as financial transparency for government officials. (The independent counsel provision of the act was allowed to lapse by Congress in 1999 after Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr’s investigation of President Bill Clinton.)

Some of the reforms implemented by Carter are ones Trump is chafing against now. For instance, inspectors general today exist in many executive agencies and departments, including ones that did not exist when Carter signed the law, like the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Trump reportedly wants to fire this inspector general because he forwarded to Congress the whistleblower complaint about the president’s attempted extortion of Ukraine. But many of Trump’s abuses are violations of norms, not of binding statutory or constitutional law. Though Carter’s most ambitious proposal for Justice Department independence was not implemented, his emphasis on the issue during the campaign and while president surely helped reestablish the norm of independence post-Nixon.

The 2020 Candidates

It should be said at the outset that the best thing that could happen for the integrity, professionalism and independence of federal law enforcement would be for Trump to lose the election. As with Nixon, Trump’s presence in office is fundamentally inconsistent with the rule of law and long-standing norms about law enforcement. By the very fact of their running for president in the first place, all of the 2020 candidates except Trump are actively working to protect law enforcement from misuse and abuse.

But a presidential campaign is a critical opportunity to do more. Promises and proposals made now will hopefully bind the conscience of the winning candidate. Widely watched and covered events like televised debates, major policy proposals, and nominating convention speeches can help educate the public about current problems and recover positive norms. Different proposals can be vetted and debated by the candidates, press, experts and voters. Electoral mandates can be sought now for reforms that will need a statutory basis.

So far, the 2020 candidates have tended to focus their attention on matters like voting rights, election security, campaign finance reform, criminal justice reform, and kitchen-table issues like health care and economic policy. To some extent this is a result of the candidates’ own choice of what to focus on, but it’s also a reflection of how the media ecosystem shapes the race. During the primary debates that have taken place so far, issues of Justice Department independence have taken a back seat: With the exception of a handful of questions concerning impeachment, debate moderators have largely kept away from the matter. In its lengthy on-the-record interviews with the candidates, the New York Times editorial board asked only one question very tangentially related to these issues (whether, in reference to Hunter Biden’s service on the board of the Ukrainian gas company Burisma, the candidates would support a law banning the children of presidents and vice presidents from serving on boards of foreign companies), and raised it with just two of the 15 presidential contenders.

As opposed to, say, health care policy—the nitty-gritty of which the candidates have discussed at length both on the campaign trail and during debates—Democratic hopefuls haven’t trumpeted their proposals for rule-of-law reforms in stump speeches, but they have discussed them in the greatest level of detail on their campaign websites and in response to a survey on executive power conducted by New York Times reporter Charlie Savage. We reviewed a wide range of materials from the campaigns of Joe Biden, Michael Bloomberg, Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. (Cory Booker and Kamala Harris had already dropped out of the race by the time we began research.) Overall, we found that Biden, Klobuchar and Warren have placed the greatest weight on the question of Justice Department independence and related issues, though they give this issue less airtime than did Carter. Buttigieg and Sanders spend even less time on these matters. And Michael Bloomberg, as far as we can tell, has not engaged on these issues at all: His website contains no mentions of them, and he has not participated in any debates so far.

Biden has largely built his campaign around the promise of a return to normalcy after what he presents as the deviation of Trumpism. For this reason, it makes sense that his campaign has, relative to the other candidates, played up the importance of reform efforts: As he put it to the New York Times, “One of the most important jobs of the next President will be to restore basic decency to the office, including honor, integrity, and a respect for the rule of law.” Biden’s campaign website includes a section on “Government Reform,” where he proposes to, among other things, issue an executive order “directing that no White House staff or any member of [Biden’s] administration may initiate, encourage, obstruct, or otherwise improperly influence specific Justice Department investigations or prosecutions for any reason”; expand the jurisdiction of the Justice Department inspector general; strengthen whistleblower protections; and mandate reporting to Congress on the reasoning behind “any change in position on a significant legal issue.” In response to a New York Times survey on the candidates’ views of executive power, Biden endorsed a “comprehensive review” of OLC opinions barring indictment of a sitting president.

Biden’s fellow moderate Amy Klobuchar often plays on similar themes of restoring values lost under Trump’s administration, pointing to the need to “bring integrity back in the White House.” Her website promises that she will “instruct the Justice Department to withdraw the Office of Legal Counsel’s opinions prohibiting the indictment of a sitting president”—not just instruct the department to review the opinions, as Biden does. She has stated that she would issue guidance directing the Justice Department not to “intervene in the transmission of a whistleblower complaint to Congress under the Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act”—presumably responding to reports that the department blocked the whistleblower complaint regarding Ukraine, which eventually precipitated the president’s impeachment, from reaching the House Intelligence Committee. Her responses to the New York Times survey mention a commitment to “providing additional protections for special counsels,” as well. (Booker twice co-sponsored a bill to do this, but neither Klobuchar nor any other current candidate who sits in Congress joined it.)

Buttigieg, like Biden and Klobuchar, plays on the idea of restoring “unity” after Trump. But his website does not provide anything about what this might mean for the Justice Department and rule-of-law reforms, and he tends not to discuss it on the campaign trail, either. This is interesting in part because his responses to the New York Times survey in September 2019 were among the most detailed and reformist of all the candidates: He proposed, among other things, “explor[ing] re-authorizing independent counsels or strengthening special counsels”; requiring Justice Department review and congressional oversight of the pardon power and ratifying a new constitutional amendment to prevent presidential self-pardons; and a review by OLC of the memos prohibiting indictment of a sitting president. More recently, in a December town hall in Iowa, Buttigieg answered a question about Trump’s criminal liability by stating, “A Department of Justice that is empowered to act independently will sort these things out without any involvement from the political side.”

Of the more left-leaning candidates, Warren is far more focused on these issues than Sanders—though, notably, both recently signed on to a Senate letter demanding Attorney General Barr’s resignation. Sanders spends little time on Trump in his speeches, debate performances and website, apart from declaring Trump to be “the most corrupt president ever.” His answers to the New York Times survey are not particularly detailed and contain no concrete recommendations, though he indicates that he would be “open to proposals to increase presidential accountability.”

Like Sanders, Warren tends to frame rule-of-law reforms in the language of countering corruption, which fits with her left-leaning focus on income inequality and regulating Wall Street: “When we’re talking corruption,” she said on the stump, “we need to call it out in the Oval Office.” But unlike Sanders, who prefers to talk about income inequality and health care, she has placed rule-of-law issues at the center of her campaign. Following the release of the Mueller report, she was one of the early Democrats and the first presidential candidate to call for Trump’s impeachment and incorporated that into her campaign rhetoric. She has issued two “plans” digging into post-Trump reforms, one focused on ensuring that “no president is above the law” and the second focused on “making the executive branch free from corruption,” among other things. But these plans spend little time on rule-of-law or law enforcement independence as such, centering instead on more traditional Warren concerns like curbing the influence of lobbyists and corporations and seeking diversity among presidential appointees. Warren has also committed to withdrawing the OLC memos on presidential indictability and backed legislation to clarify Congress’s intent that the president is indictable and may be charged with obstruction of justice. Recently, in advocating for congressional oversight of the executive branch following Trump’s acquittal, she emphasized her proposal to institute an independent “Justice Department Task Force” to “investigate corruption during the Trump administration and to hold government officials accountable for illegal activity.”

It’s worth noting that—ironically, for a package of proposals aimed at restoring Justice Department integrity—Warren is promising as president to direct prosecutors to look for crimes committed by specific individuals. This appears to us only somewhat less problematic than former candidate Kamala Harris’s suggestion while campaigning that, during a Harris administration, Trump would be prosecuted for obstruction of justice. Both proposals are a long way from Trump-led chants of “Lock her up” and Trump’s public demands that the Justice Department investigate and prosecute his political enemies. But they still cross into the murky territory of political involvement in prosecutorial decision-making. For that matter, Warren’s and Klobuchar’s promises to instruct OLC to withdraw its memos on presidential indictability risk furthering the perception—magnified by the aggressive and often questionable positions the office has taken under the Trump administration—that OLC does not provide good-faith legal advice on issues of high priority but is rather a mere arm of presidential power.

* * *

Our goal here is not to endorse any particular reform to help protect the independence and integrity of federal law enforcement and, hence, the rule of law in this country. That said, we find several ideas proposed by the candidates attractive, such as Biden’s proposed executive order and expansion of the remit of the Justice Department inspector general, Warren’s call to clarify that the president is subject to obstruction of justice statutes, and Klobuchar’s promise to look at improving the special counsel provisions. (Some thoughtful proposals have been made by outside groups and experts also.)

So why aren’t the candidates addressing this issue more? Perhaps they simply don’t feel the subject matter will win them votes. During the 2018 midterm election, the Democratic Party focused its messaging on Trump’s efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act and the effects of the Trump tax cut on middle-class taxpayers, believing this would more viscerally appeal to voters than would discussion of Trump’s abuses of power. Likewise, the New York Times reported recently that Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi plans for the party’s 2020 message to be, “Health care, health care, health care.” The presidential candidates may be making a similar calculation.

The candidates may also worry that a significant tension exists between good answers and popular answers to questions about federal law enforcement. Among Democrats and anti-Trump independents and Republicans, there is justifiable anger about the president’s many abuses and transgressions. In part because potential criminal liability for Trump is still on the table—not to mention liability for some of his associates—any effort to discuss Justice Department independence gets tangled up in difficult questions of how involved a president should be in reaching decisions about whether or whom to prosecute in politically sensitive cases. Asked their view on accountability for Trump, for example, candidates either end up saying something clear and decisive but, from a rule-of-law perspective, wrongheaded—like Harris’s promise to prosecute Trump or Warren’s call for a task force—or sounding wishy-washy by emphasizing that these decisions are up to the Justice Department. Carter was spared from this bind in 1976: Ford’s pardon of Nixon removed any question of criminal prosecution of the former president, and the criminal cases against others directly implicated in Watergate had already been resolved.

Of course, the historical record on Carter’s platform includes his promises from both the primary and the general campaign. Perhaps Justice Department independence and reforms will become a bigger 2020 issue after the primary, when the Democratic nominee will have to spend more time contrasting him- or herself to Donald Trump. At the same time, if, say, Sanders wins the party’s nomination, it seems just as likely that he will continue to build his campaign around a message focused on health care and income inequality.

Even though the issue of law enforcement independence and impartiality is not a top-tier concern for voters—and can be tricky to explain to lay audiences—we hope the candidates vying to take on President Trump give more attention to this issue. Law enforcement deployed to serve personal or political agendas is a favorite and crucially important tool of every modern tyranny. A decent, liberal-democratic society must find a way to have politically accountable leaders set broad law enforcement priorities while leaving almost all decisions about specific cases to independent and impartial actors. Striking the right balance is hard. But failing to propose countermeasures to Trump’s abuses should, for serious candidates for the presidency in 2020, be unthinkable.

Thanks to Hadley Baker, Hannah Kris and Elliot Setzer for their assistance in researching this piece.