75 Years After a Historic Meeting on the USS Quincy, U.S.-Saudi Relations Are in Need of a True Re-think

The crown prince is toxic. It's time for fundamental changes.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on Order from Chaos.

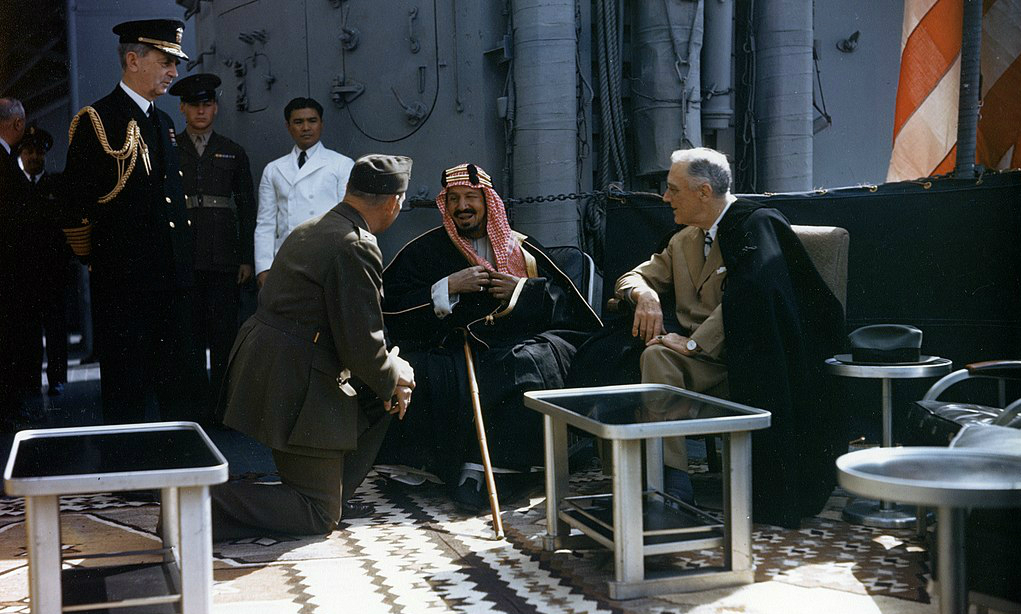

On Valentine’s Day 1945, President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with Saudi King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud on an American cruiser, the USS Quincy, in the Suez Canal. It was the dawn of what is now the longest U.S. relationship with an Arab state. Today the relationship is in decline, perhaps terminally, and needs recasting.

FDR and Ibn Saud, as they were known popularly, could not have been more different. FDR was in his fourth term as the elected president of the most powerful country in the world, and on the eve of winning World War II. He had traveled the world and was returning from the Yalta summit with Winston Churchill and Josef Stalin. He was gravely ill and had only weeks to live. His blood pressure was 260 over 150. But he was convinced that Saudi Arabia would be crucial to America in the post-war world, thanks to its oil.

Ibn Saud had never been to sea before, or outside the Arabian Peninsula except for a brief trip to Basra, Iraq. He was a warrior who had created the modern Saudi kingdom through endless battles. He had little experience in international diplomacy. He was an absolute monarch backed by the fanatical Wahhabi clergy. But he had sent two of his sons, Faisal and Khaled, to America in 1943 to meet Roosevelt, tour across the country, and report home that America was the strongest and most advanced country in the world.

The substance of this meeting on the Quincy was dominated by a disagreement over the future of Palestine: FDR argued for a Jewish state, and Ibn Saud protested that the Jews should get their state in Bavaria. But the substance was secondary to the good atmosphere of the session. The president abjured his usual cigarette and cocktail to honor the king’s Islamic sentiments. They exchanged gifts and left very impressed with each other.

And they forged the basis of a long relationship: America’s security guarantees for the kingdom in return for access to affordable energy supplies. The relationship has had ups and downs but every American president has courted the Saudis. None has been as accommodating—even sycophantic—than Donald Trump. He has praised the Saudis for buying American weapons that they have not actually purchased. He has continued support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen, which has created the worst humanitarian catastrophe in the world and which costs the kingdom a fortune it doesn’t have, given low oil prices.

Worst, the administration has ignored the brutal murder of Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist, in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey. The execution was the work of the Saudi state, according to the United Nations investigation, and the mastermind was the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The president has absolved his favorite.

But it won’t work. The crown prince is toxic, his reputation permanently stained. And the bargain struck on the Quincy is out of date. The United States doesn’t need Saudi oil anymore, it is almost energy independent. The White House has sent American combat troops back to Saudi Arabia (they left in 2003), but they did not deter the Iranians from striking the kingdom’s most critical oil facilities last September. The Saudis were literally shaken out of their complacency, and their acute vulnerability was exposed to all.

The next president should bring American troops home immediately from the kingdom and cut off all military support to the Saudis, at least until there is a permanent political settlement in Yemen. Saudi diplomatic facilities in the United States should be shut or stripped down because they are used to spy on dissidents like Khashoggi. Saudi soldiers in the U.S. for training or other tasks should be sent home. The Saudis should understand that anyone implicated in the Khashoggi murder will not be welcome in the U.S. The attorney general should review what judicial process may apply to the case.

All of this should be part of a larger review of policy toward the region to reduce our military footprint and use more diplomacy. Iran should be engaged, and the Iran nuclear deal should be revived and strengthened. A serious political process between Israel and the Palestinians should be initiated, not the sham deal announced by this administration. It will certainly be challenging, but it is time for fundamental changes.