A Plea and a Letter: An Update From Coffee County

Two new developments in the Coffee County saga.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The day after a Georgia grand jury indicted then-President Donald Trump and 18 others on racketeering and other charges, I wrote an exhaustive account of one aspect of the alleged conspiracy to overturn the results of the 2020 election: the unauthorized copying of voting equipment in Coffee County, Georgia.

That account told the story of how a group of election officials and Republican Party operatives in a rural county won the ears of Trump’s top lawyers and allies as they sought to discredit the results of the 2020 election. It recounted how those efforts culminated in the events of Jan. 7, 2021: As the nation reeled from the aftermath of an attempted insurrection in Washington, D.C., a local GOP chairperson named Cathy Latham and a bail bondsman named Scott Hall accompanied a computer forensics team into the elections office in Douglas, Georgia.

Inside, they were joined by two local elections officials, Misty Hampton and Eric Chaney, and a former member of the elections board, Ed Voyles. According to court documents, the forensics team—a group of employees with an Atlanta-based forensic data firm called SullivanStrickler LLC—had been hired by Sidney Powell, a lawyer working with Trump’s legal team. Over the course of several hours, the SullivanStrickler employees handled, scanned, and copied the state’s most sensitive voting software and equipment.

All of this apparently took place without authorization from any court of law or government body.

Since Lawfare published that story on Aug. 15, two new developments have arisen that warrant an update. The first is a factual development that serves as an epilogue of sorts for one individual involved in the voting system breach. The second development explains what had previously been a gap in the record of the Coffee County saga.

A Plea Deal

Last Friday, bail bondsman Scott Hall became the first of Trump’s co-defendants in Georgia to reach a plea agreement with Fulton County prosecutors.

As plea deals go, Hall’s is a generous one. When a grand jury returned the sweeping indictment against Trump and 18 others in Fulton County on Aug. 14, Hall was initially charged with violating Georgia’s racketeering statute, as well as six felony counts related to the Coffee County breach, including conspiracy to commit election fraud, conspiracy to commit computer theft, conspiracy to commit computer trespass, conspiracy to commit invasion of privacy, and conspiracy to defraud the state.

As a part of his negotiated plea, Hall’s charges were instead reduced to five misdemeanor counts of conspiracy to commit intentional interference with the performance of election duties.

During a surprise plea hearing before Judge Scott McAfee last week, Hall pleaded guilty to each of those misdemeanor counts. He was sentenced to five years of probation and must also pay a $5,000 fine.

Additionally, Hall agreed to abide by a litany of conditions. Among other conditions, he must refrain from poll watching activities, write an apology letter to the state of Georgia, and complete 200 hours of community service.

The most consequential of the agreed-upon conditions require Hall to cooperate with the district attorney’s office for the duration of the case. He must testify truthfully at any future proceedings, including at trial. And he is required to provide “information and documents” as requested by Fulton County prosecutors.

Notably, another condition requires Hall to “provide access to any investigator used, including Preston Halliburton.” The precise meaning of this condition is unclear; its purpose may be to effectuate a waiver of privilege for any investigator Hall used in preparing his defense.

But the specific reference to Haliburton is interesting. Haliburton, a Georgia attorney, has not been accused of wrongdoing and does not appear to fit the description of any of the 30 “unindicted co-conspirators” listed in the indictment.

Still, Haliburton may have personal knowledge of the events leading up to the voting system breach. According to the testimony of Bernard Kerik before the House select committee on Jan. 6, it was Haliburton who arranged for a “whistleblower” from Georgia to meet with Rudy Giuliani in Washington, D.C., sometime around December 2020. Later, Haliburton represented both Giuliani and Cathy Latham—the former Coffee County GOP official accused of coordinating the breach—at a Dec. 30, 2020, state legislative hearing, where Latham claimed “whistleblower” status. The next day, Haliburton’s email address shows up in a text exchange between Eric Chaney and Misty Hampton, two Coffee County officials who were present during the copying that occurred on Jan. 7, 2021. And Haliburton appears to be referenced in a Jan. 1, 2021, message sent by Trump attorney Katherine Freiss to a SullivanStrickler employee, in which she writes that her team has been “granted access” to Coffee County systems and that she is “putting details details together now with Phil, Preston, Jovan etc.” “Preston” is an apparent reference to Haliburton.

All told, Hall’s cooperation signals an early victory for the prosecution as it prepares to try two of Hall’s co-defendants, Sidney Powell and Kenneth Chesebro, at the end of this month. The full scope of Hall’s potential testimony at that trial remains unclear, but his cooperation is likely to be particularly useful with respect to the state’s case against Powell, who is not only charged with racketeering but is also charged with a number of felony counts related to the Coffee County breach.

According to the indictment, Powell allegedly entered into a written engagement agreement with SullivanStrickler in Fulton County, Georgia, to conduct an analysis of Dominion Voting Systems equipment in Michigan and elsewhere. Prosecutors allege that the “unlawful breach of election equipment in Coffee County, Georgia, was subsequently performed under this agreement.” As Lawfare recounted in “What the Heck Happened in Coffee County, Georgia?,” court documents show that on Jan. 7, 2021, Hall flew to Douglas, Georgia, where he spent several hours inside the elections office as SullivanStrickler employees made forensic copies of the county’s voting equipment. The indictment also alleges that on the day before the breach, Hall spoke on the phone with another alleged co-conspirator, Latham, about gaining access to the elections board office.

Powell’s attorney has claimed in court filings that she had nothing to do with the voting system breach and that she only learned about it after the fact. Hall, to that end, may be able to provide key documents or testimony linking Powell to the voting system breach ahead of Jan. 7, 2021.

But it is a mistake to think that Hall’s utility as cooperator is isolated to the Coffee County prong of the alleged conspiracy to overturn the election. To the contrary, the indictment indicates that Hall’s connections to his co-defendants extends well beyond those who were involved in the Coffee County saga. The indictment alleges that David Shafer, the former Georgia GOP chair who was also charged in Fulton County, described Hall in a Nov. 20, 2020, email as someone who “has been looking into the election on behalf of the President at the request of David Bossie.” (Bossie is a conservative political activist. Hall is reportedly the stepbrother of Bossie’s wife.)

Elsewhere in the indictment, prosecutors allege that Hall was in contact with another co-defendant who was a top ally of then-President Trump in the wake of the 2020 election: former Justice Department official Jeffrey Clark. Clark’s criminal charges stem largely from his (ultimately unsuccessful) efforts to persuade Justice Department officials to send a letter to Georgia state officials. According to prosecutors, the letter falsely asserted that the department had “identified significant concerns that may have impacted the outcome of the election.” The indictment alleges that around the time that Clark was pressuring Justice Department officials to send that letter, he had a 63-minute phone call with Hall to discuss the 2020 election in Georgia.

Beyond Hall’s call with Clark, the indictment also references a number of calls placed between Hall and Robert Cheeley, as well as a call between Hall, Cheeley, and Trevian Kutti. Cheeley is alleged to have made false claims about the vote count in Georgia to members of the Georgia state senate and to have conspired to put forth fake electors; Kutti, meanwhile, is charged in relation to the alleged intimidation and harassment campaign against Georgia election worker Ruby Freeman. While the indictment does not detail the substance of these calls, it alleges that they constitute “overt acts” in furtherance of the conspiracy.

All of which is to say that Hall’s cooperation could be valuable for the prosecution across multiple prongs of the alleged racketeering conspiracy, and in proving up the discrete charges against multiple defendants.

To be sure, Hall is unlikely to be the last of the remaining 18 defendants to strike a deal.

The “Letter of Invitation”

When Lawfare published the first installment of the Coffee County caper, a central mystery in the saga remained unresolved: Did a Trump campaign attorney receive a “written invitation” to access and copy voting systems in the rural county? If so, who wrote the letter? And what did it say?

Text messages and documents filed in civil litigation hinted at the existence of such a letter. Days before the breach, Katherine Freiss—a Trump attorney who worked closely with Giuliani—messaged an employee of the Atlanta-based forensics firm SullivanStrickler: “Hi! Just handed [sic] back in DC with the Mayor,” she said. “Huge things starting to come together! Most immediately, we were granted access—by written invitation!—to the Coffee County Systens [sic]. Yay! Putting details together now with Phil, Preston, Jovan etc. Want to give you a heads up for your team. Will be either Sat or Sun this weekend. More soon :)).”

The same day, according to a privilege log produced in a defamation case brought against Giuliani, Friess sent a “Letter of invite from Coffee County GA” to several Trump associates working on 2020 election issues, including former New York Police Commissioner Kerik.

But the letter was never produced in the Curling v. Raffensperger case—which sought to compel state officials to switch from electronic machine voting to ballots bubbled in by hand—or other litigation, and open records requests for such a letter produced no responsive documents.

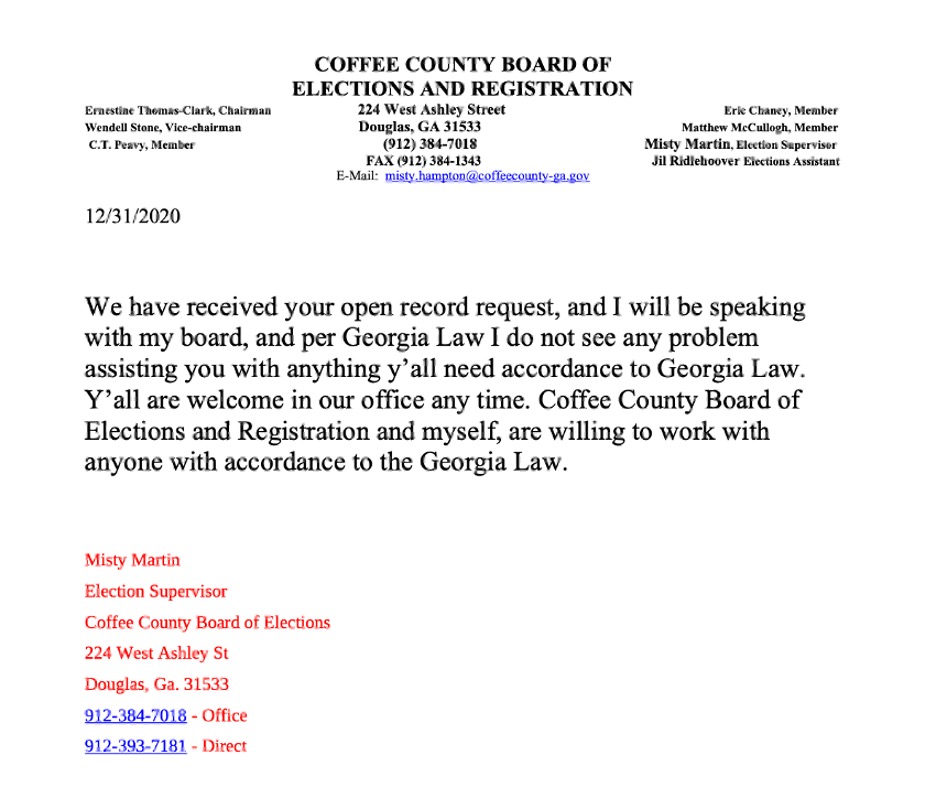

Last week, the purported invitation ultimately surfaced in a motion filed by Sidney Powell’s attorney, Brian Rafferty. The letter was authored by Misty Martin, AKA Misty Hampton, one of Powell’s co-defendants who at that time served as the county’s elections supervisor. According to Powell’s counsel, the letter proves that “Coffee County officials invited and approved the forensic collection” that occurred in January 2021. It reads as follows:

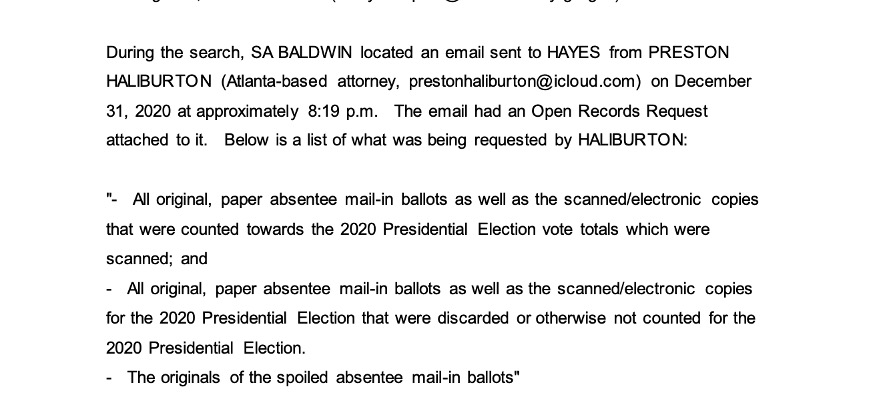

The letter purports to be a response to an open records request. That open records request was apparently sent by Preston Haliburton, the above-mentioned attorney who represented Giuliani and Latham at the Dec. 30, 2020, state legislative hearing. According to a Georgia Bureau of Investigation report filed as an exhibit in one of Powell’s briefs, the request reads as follows:

The content of these letters, as well as statements from local and state officials, cast serious doubt on the assertion that the letter “authorized” the copying carried out in January 2021.

First, consider the content of the letter. Most obviously, it says nothing whatsoever about copying voting equipment or software. The open records request that apparently prompted the letter is limited to scanning “absentee mail-in ballots” from the 2020 election. Yet on Jan. 7, 2021, SullivanStrickler employees created forensic copies of virtually every piece of Coffee County’s elections equipment, including the Election Management System (EMS) server, the poll pads, the ballot marking devices, and the ballot scanner, according to court documents. “Y’all are welcome in our office any time” can hardly be construed as an invitation for a third party to access and copy virtually everything in the county elections office.

Even if it could be construed as such, nothing in the letter indicates that the board of elections approved any access to county elections equipment. Instead, Hampton says, “I will be speaking with my board.”

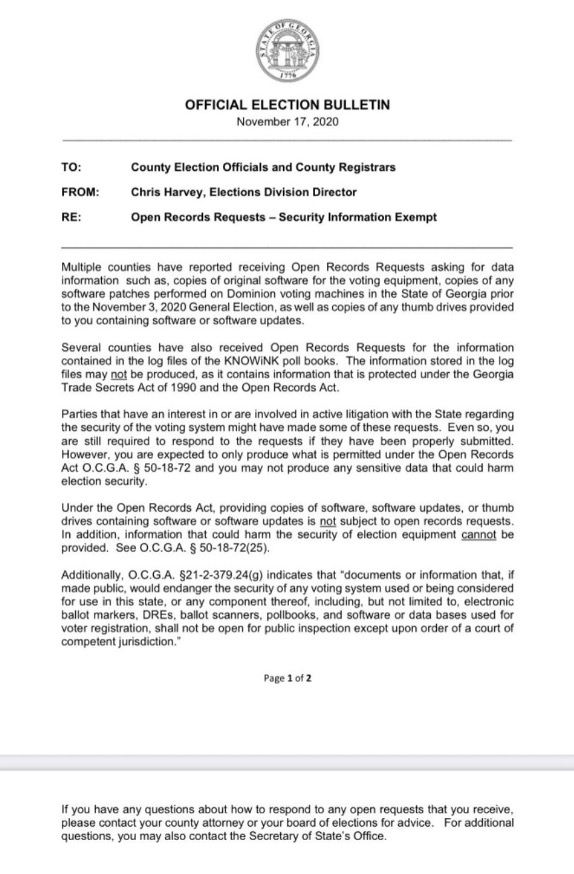

Further, at least some of the voting data copied on Jan. 7, 2021, would not be producible under Georgia’s Open Records Act. Indeed, a Nov. 17, 2020, bulletin sent to county election officials throughout the state of Georgia specified that “information that could harm the security of election equipment cannot be provided.”

Additionally, state and local officials have repeatedly stated that the work was not “authorized.” The secretary of state’s office has publicly referred to the incident as “unauthorized access to the equipment that former Coffee County election officials allowed in violation of state law.” A representative for the Coffee County Board of Elections has testified that the board as an institution neither knew about nor authorized the entry and copying. Fulton County prosecutors recently subpoenaed that individual, Wendell Stone, to testify in Powell’s upcoming trial, according to documents obtained by Lawfare through open records requests.

There are questions about the letter that remain unanswered. It’s unknown, for example, who else besides Hampton might have been involved in drafting it. In deposition testimony, Hampton claimed that Chaney, a member of the board, had directed her to allow the copying of the election systems. (Chaney would not have had lawful authority to unilaterally direct Hampton to do so, as decisions of the board require a quorum, according to Stone’s deposition testimony in the Curling litigation.)

But for now, the production of the letter answers several questions at the heart of the Coffee County saga and the criminal case it spurred. Yes, the letter Freiss referred to in her message to SullivanStrickler exists. Yes, Misty Hampton is the apparent author. No, it does not “authorize” the copying of election equipment that occurred on Jan. 7, 2021.

.jpg?sfvrsn=676ddf0d_7)