About That Pelosi Video: What to Do About ‘Cheapfakes’ in 2020

In the summer of 2016, a meme began to circulate on the fringes of the right-wing internet: the notion that presidential candidate Hillary Clinton was seriously ill. Clinton suffered from Parkinson’s disease, a brain tumor and seizures, among other things, argued Infowars contributor Paul Joseph Watson in a YouTube video. The meme (and allegations) were entirely unfounded.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

In the summer of 2016, a meme began to circulate on the fringes of the right-wing internet: the notion that presidential candidate Hillary Clinton was seriously ill. Clinton suffered from Parkinson’s disease, a brain tumor and seizures, among other things, argued Infowars contributor Paul Joseph Watson in a YouTube video. The meme (and allegations) were entirely unfounded. As reporter Ben Collins describes, however, Watson’s baseless accusation nonetheless spread through the right-wing mediasphere and then reached mainstream audiences through Fox News. “Go online and put down ‘Hillary Clinton illness,’ take a look at the videos for yourself,” Donald Trump’s advisor Rudy Giuliani urged Fox viewers.

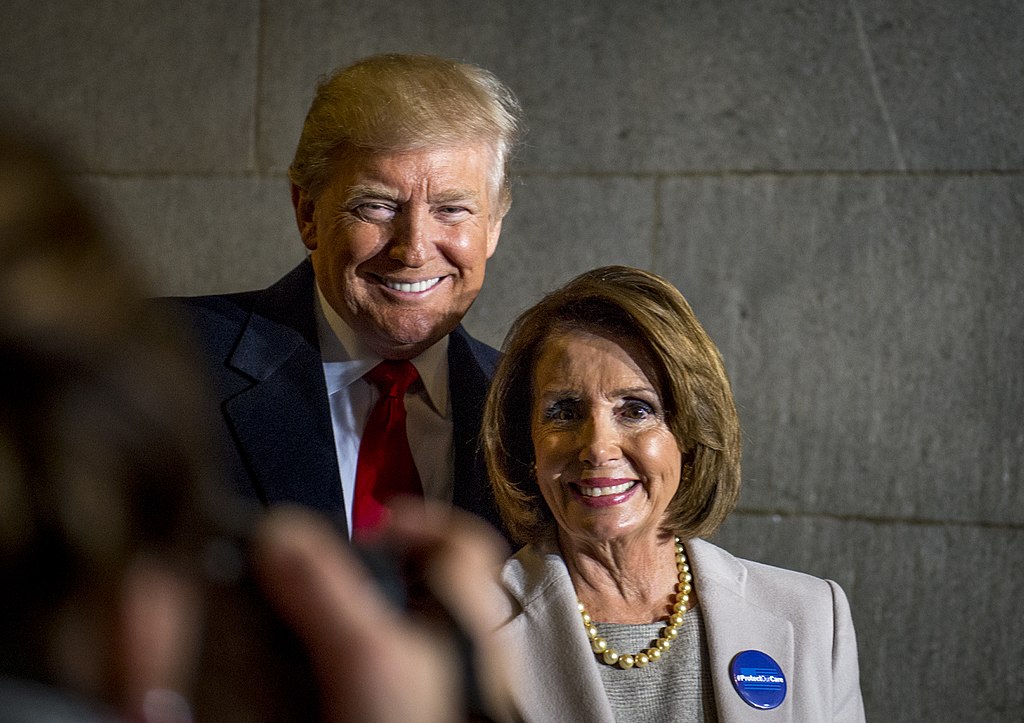

Almost three years to the date, Giuliani is peddling a similar message about the Democratic Party leader’s health. On May 23, deceptively edited videos of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi began to circulate on Facebook, with footage of a speech given by Pelosi altered to make her appear drunk or unwell. “What is wrong with Nancy Pelosi?” Giuliani tweeted, linking to one of the videos. “Her speech pattern is bizarre.” (In an obvious retreat, Giuliani later deleted the tweet.) Later that evening, the president himself tweeted out a link to a different deceptive video, first aired on Lou Dobbs Tonight on Fox News, that used choppy editing to make Pelosi appear to stammer. Though the Washington Post had published an article warning about the deceptively edited Pelosi videos hours before Giuliani’s and Trump’s tweets, that proved no impediment to the videos’ going viral.

These sorry episodes remind us that we need not wait for technological change to make disinformation cascades possible. True, the arrival of deepfakes (that is, highly realistic synthetic video or audio making it seem that real people said or did something they never said or did) poses a serious threat along these lines, as two of us (Chesney and Citron) have argued (initially on Lawfare and in Foreign Affairs and in much more detail in this forthcoming California Law Review article). But it would be a mistake to think that serious harm to our democracy can come only from a deepfake.

To be sure, less convincing forms of fraud (now sometimes called cheapfakes or shallowfakes) are comparatively easy to detect. But as we have seen, they can still cause tremendous mischief. This should come as no surprise, for many of the same considerations that drove us to warn about the dangers of deepfakes apply with cheapfakes.

The bottom line is this: The interaction of social-media information dynamics, common cognitive biases and the declining influence of traditional media has enabled the rapid-fire spread of falsehoods. The internet has democratized access to all information, including damaging lies. Though it is relatively easy in theory to debunk most cheapfakes—particularly if they manipulate recordings of events for which reliable, authentic copies are available—the sad fact remains that real recordings usually fail to catch up to the salacious fakes. And far too often, the fakery is believed, particularly when the thrust of the fraud tends to confirm preexisting beliefs.

The stakes are high, and the Pelosi example is just one example of far too many. Earlier this year, a young female White House staff member tried to take a microphone out of the hands of CNN reporter Jim Acosta. It was a tense and complicated moment, but an Infowars conspiracy theorist made it far worse with a doctored video of the incident. The video sped up the key moment in a way that tricked viewers into believing that Acosta brought his hand down hard against the arm of the staffer.

To say this was misleading fails to capture the degree of fraud the video perpetrated. Debunking was easy enough: Because plenty of unadulterated videos of the event existed, people exposed the trickery in short order. But, to no avail, as the White House press secretary had already circulated the fraudulent video. The truth had no chance of catching up to the lie.

This past week is a reminder of how easily such frauds can spread through the information ecosystem, giving the country yet another truth fiasco. Even though Giuliani deleted his tweet after receiving criticism (and, somewhat incoherently, apologized for it), the damage was done. And the president’s tweet remains unapologetically live.

To be sure, defamation in American politics is nothing new. Hamilton and Jefferson played that game too. What is different today is that the falsehoods involve firsthand visual and audio “evidence” that our eyes and ears are deeply inclined to trust (not just written words that might more readily be dismissed), and the frauds can rapidly reach countless individuals.

What can be done? It is tempting to respond with a fatalistic shrug that suggests a resolve to live with such nonsense, no matter how unpleasant. But initial steps can and should be taken, especially as we look toward the 2020 election cycle.

First things first: The campaigns themselves have work to do. They must be prepared to deal rapidly and vigorously with what might be called “attack fakes,” just as they already respond to conventional attack ads. For starters, candidates should acknowledge and denounce the practice of creating or circulating attack fakes, starting with the Pelosi video. Education about the practice matters, even though it risks turning each and every one of us into truth skeptics, something two of us have called the Liar’s Dividend. That is, an excessively skeptical environment will be a welcome environment for liars who seek to deny responsibility for true events—and it may only be a matter of time before the president of the United States, who has already suggested in private that authentic audio from the Access Hollywood tape was faked, avails himself of this tactic publicly.

Nevertheless, anyone running for office in 2020 should have a plan for dealing with attack fakes. In practical terms, this means that campaigns should devote resources to detecting and debunking attack fakes. No one is in a better position to document and authenticate where candidates were, what they were saying and what they were doing in actuality.

Campaigns also should establish hotlines to the dominant social media platforms (and vice versa), allowing them to report the emergence of attack fakes. The companies could then decide whether to remove and filter an attack fake, demote it, flag it in some conspicuous way and so forth.

Of course, determining whether an alleged attack fake is worth flagging, demoting or even blocking is no easy task. As our prior work has explored, platforms have struggled to address harmful content in other settings, from nonconsensual pornography and threats to terrorist content and hate speech. In the context of political campaigns, it will be no easier. The line between an attack fake that affirmatively misleads the public about what a candidate did or said and a video that has been altered for the important purposes of parody or satire will not always be clear.

The difficulty of the marginal cases is not an excuse for inaction across the board, however. There are steps that can and should be taken. As an initial matter, social media companies should ban (in their terms of service) video or audio depictions of a candidate that is more likely than not to mislead a reasonable viewer into believing that the person actually said or did something that he or she did not say or do (perhaps including a safe-harbor option for content expressly labeled as parody, satire or the like).

We are mindful that the platforms are wary of being accused of bias if they intervene with respect to political speech. Lawmakers and activists already have criticized social media companies for banning individuals (like Infowars founder Alex Jones) from their services. They have been accused of playing politics rather than even-handedly enforcing terms-of-service (TOS) agreements even when there was a clear case of a TOS violation such as inciting violence, doxxing, making threats or engaging in false advertising. But the stakes with elections are too high not to take action at least in the clear cases.

Last week’s experience shows us why we should worry. YouTube quickly decided to ban the Pelosi video, but Facebook refused to do so despite concluding that it was problematic. In lieu of a ban, it has settled on demoting the video (that is, altering its recommendation engine so that it does not draw still-more attention to the already much-circulated video) while also adding a flag with a milquetoast caution that third-party fact-checkers find the video misleading. “We think it’s important for people to make their own informed choice for what to believe,” said Monika Bickert, Facebook’s vice president for policy and counterterrorism, when pressed by Anderson Cooper on why the company had chosen to allow the video to remain live.

The version of the video posted on Facebook has millions of views at this point, despite these steps. This demonstrates the extent of the challenge. Some people will watch flagged content precisely because of the controversy. (According to Twitter co-founder Biz Stone, only 300 people on Twitter watched the doctored Pelosi video before media outlets began reporting on it.) Some will distrust the fact-checkers or Facebook itself. Others will not click through to see what, in particular, the fact-checkers thought about it. This suggests stronger medicine might be in order, at least in the context of an election.

What might that entail? The question is complicated because taking any action will start us down a slippery slope. If the Pelosi video should be the basis for some responsive measure, is the same measure warranted for the Lou Dobbs Tonight video that the president circulated? What about videos that amount to edgier forms of satire, not clearly identifiable as such through their context? The answers must not depend on partisan preference.

Bearing that challenge in mind, it might be best for the platforms to be especially wary about the harshest solution: outright banning of content (booting the video off the platform and using a hash of the file to spot and remove or block other iterations of it, and sharing that hash with other platforms, which can make their own decisions on whether and how to act on it). This suggests that banning or removing content should be a remedy used only in the most extreme and obvious circumstances. Alas, the partisan divide over platforms’ efforts to remove disinformation, in which politicians and commentators on the right commonly complain that the platforms are biased against their political beliefs, may make it difficult even to settle on what an “obvious” situation could be.

In the bulk of cases, then, it may be best to embrace a more-aggressive combination of demotion and flagging that allows the content to stay posted, yet sends a much louder message than the example set by Facebook’s current flagged-by-third-party approach. For example, anyone who clicks on the video might first be presented with a click-through screen directly stating that the platform itself has determined that the video has been meaningfully altered, and asking the user to acknowledge reading that statement before the video can be watched. If accompanied by a robust and transparent mechanism through which such categorizations can be challenged, some such “nudge” solution might prove to be the best available option in the edge cases.

It is increasingly clear that the integrity of the 2020 presidential election will be challenged by misinformation just as much, if not more so, than the 2016 election was. This time, though, the country has advance warning. There is no easy solution to the challenge of cheapfakes. This is precisely why both platforms and campaigns need to begin thinking seriously about how to address the problem now.