The Abuse of the Pardon Prevention Act Would Criminalize Politics

Right now, the Abuse of the Pardon Prevention Act may seem like a prudent idea. But the new bill would have dangerous ramifications for American politics moving forward.

On July 23, the House Judiciary Committee held a markup of a new bill, the Abuse of the Pardon Prevention Act. (Bob Bauer and Jack Goldsmith wrote about it here.)

To date, Congress has not substantially regulated the president’s pardon power. This bill, by contrast, attempts to regulate the president’s pardon power in two ways. Section Two of the bill requires the attorney general to submit certain information about presidential pardons for specific offenses identified in the bill. Section Three of the bill amends the federal bribery statute to make clear that a (former) president can be prosecuted for accepting a bribe in exchange for a pardon. (We put the word “former” in parentheses because, under long-standing Justice Department policy, the sitting president cannot be indicted for a federal offense.) The House also introduced a related bill, the No President is Above the Law Act. This bill would toll all federal statutes of limitation that may run against the president during his time in office. This post will focus on Section Three of the Abuse of the Pardon Prevention Act.

The now in-force federal bribery statute, 18 U.S.C. § 201, applies to federal “public official[s].” Section 201(a)(1) defines this category to include members of Congress, as well as “an officer or employee or person acting for or on behalf of the United States.” There is some doubt whether this language reaches the president and vice president. The Abuse of the Pardon Prevention Act would amend that subsection, so that it would expressly apply to “an officer or employee or person, including the President and Vice President, acting for or on behalf of the United States” (emphasis added).

The statute is limited to certain “official act[s].” Section 201(a)(3) defines this category to include “any decision or action on any question, matter, cause, suit, proceeding or controversy, which may at any time be pending, or which may by law be brought before any public official, in such official’s official capacity, or in such official’s place of trust or profit.” The new bill would amend § 201(a)(3) by adding several categories of “official act[s]”: “any pardon, commutation, or reprieve, or offer any such pardon, commutation, or reprieve.”

The statute defines four substantive offenses. First, § 201(b)(1) applies when a person “directly or indirectly, corruptly gives, offers or promises anything of value to any public official ... with intent—to influence any official act.” Second, § 201(b)(2) applies when a “public official ... directly or indirectly, corruptly demands, seeks, receives, accepts, or agrees to receive or accept anything of value personally or for any other person or entity, in return for ... being influenced in the performance of any official act” (emphasis added). The “personally” “receive or accept” element is essential for the traditional understanding of bribery: Only things of value that can be personally accepted are bribes. Things of value that cannot be personally accepted are not bribes. As we will discuss below, an official act performed by a government official cannot be personally accepted by an alleged wrongdoer.

The new bill would amend § 201(b)(2) so that it expressly applies to presidential pardons. We added the new text in italics:

Whoever ... directly or indirectly, corruptly gives, offers, or promises anything of value including, for purposes of this paragraph, any pardon, commutation, or reprieve, or offer any such pardon, commutation, or reprieve to any person, or offers or promises such person to give anything of value to any other person or entity, with intent to influence the testimony under oath or affirmation of such first-mentioned person ... shall be fined ... or imprisoned ....

Third, § 201(b)(3) repeats much of the language 201(b)(1) but extends the range of criminal conduct beyond just “official act[s].” Fourth, § 201(b)(4) makes it a crime to “directly or indirectly, corruptly demand[], seek[], receive[], accept[], or agree[] to receive or accept anything of value personally or for any other person or entity in return for being influenced in testimony under oath.” Once again, the thing of value must be personally accepted. This part of the statute is not limited to “public officials” or “public acts.” The new bill does not modify either of these sections.

The most significant element of the bill is the redefinition of “public officials” to include the president and vice president. This redefinition is designed to avoid the so-called clear statement rule. (Blackman wrote about that rule here and here.) To avoid difficult constitutional questions, the federal courts will require Congress to clearly state that a statute applies to the president. If a statute does not expressly apply to official actions taken by the president during his tenure, under the clear statement rule, then the courts will presume that Congress did not intend for the statute to apply to those actions. Under the Constitution, only the president can issue pardons. The vice president cannot issue pardons. This provision is designed to reach the president, and the president alone.

The Abuse of the Pardon Prevention Act has several significant problems. As a threshold matter, it is not clear that this bill is necessary to prohibit the president from accepting bribes, as that term has been traditionally understood. We think federal law already would permit the prosecution of a (former) president for having accepted or solicited a bribe during his term as president. The Constitution expressly states that the president can be impeached for bribery. Accepting a bribe, as that term is traditionally understood, is beyond the president’s Article II powers. Because such wrongdoing would go beyond the president’s Article II powers, Congress can criminalize such actions with or without a clear statement. In 1995, the Office of Legal Counsel determined that the bribery statute could be applied to the president, even absent a clear statement. This 1995 memorandum, however, at its core, considered a different question: whether a nepotism statute applies to federal judges.

Consider an example. The president asks someone for a suitcase full of cash in exchange for his granting a pardon. With those facts, the president could be impeached for bribery. In such a case, we can be fairly certain the transaction was not publicly spirited, even in part, because the bargain is intended to be kept secret; the money is kept in a suitcase, as opposed to a bank; the income is not declared; and the president personally accepts the cash. Even under the present version of § 201, we think a (former) president could be indicted for bribery on these facts.

This new bill, however, creates other significant problems far beyond pardons. Specifically, by eliminating the clear statement rule, Congress would subject the president to a theory of “bribery” that is more expansive than the suitcase-full-of-cash scenario we described above.

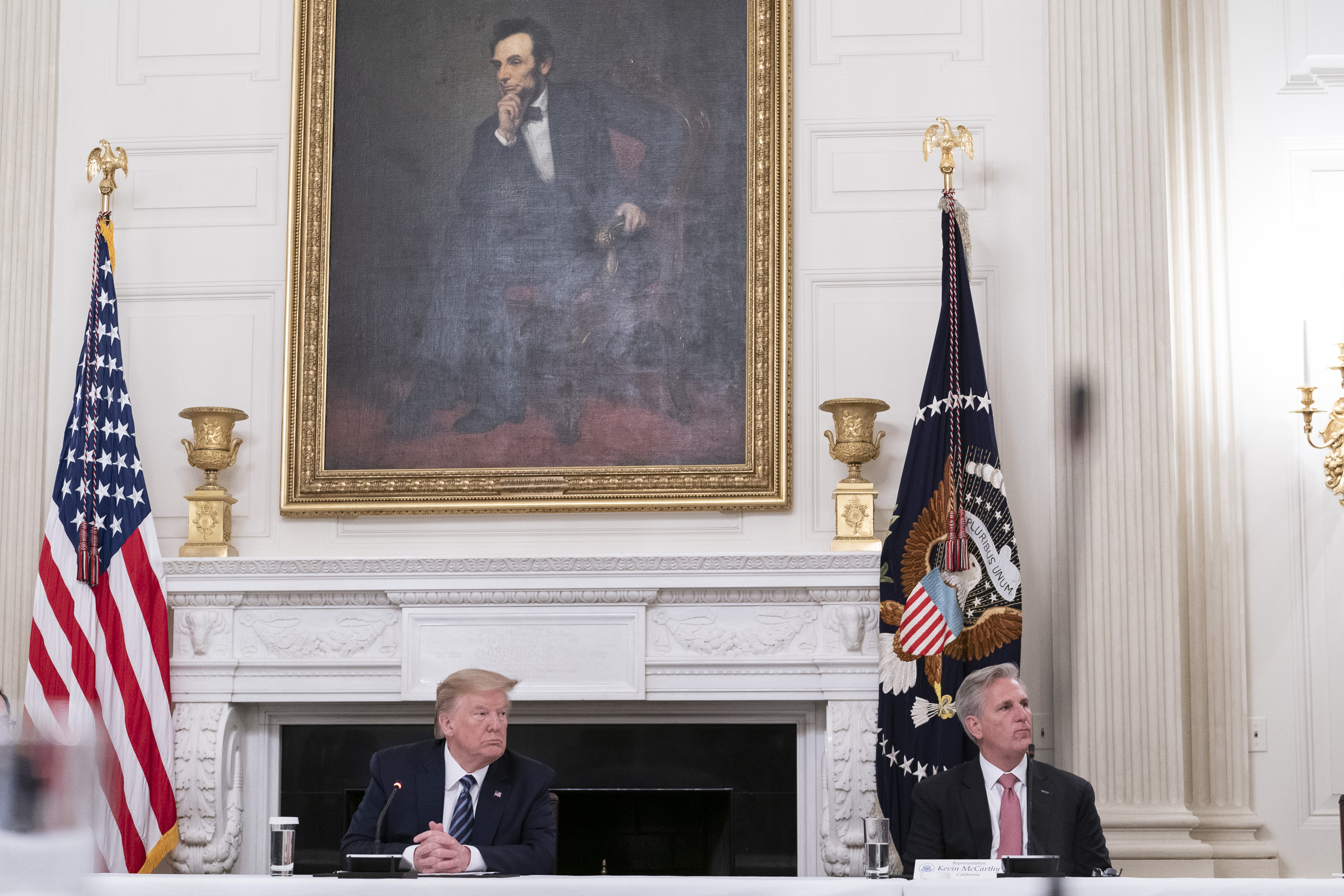

Indeed, we think this theory of statutory bribery would resemble the broader theory of bribery that was debated during the impeachment process. The same Judiciary Committee that marked up this bill considered an article of impeachment based on bribery against President Trump. (Ultimately, the House brought articles focusing on “abuse of power” and “obstruction of Congress.” House leadership chose not to adopt an article of impeachment that expressly included a bribery-based theory.) Our position was that any such theory of bribery would be problematic. In December 2019, we wrote about the difficulties the House would face in bringing an article of impeachment based on an overly broad theory of bribery.

The Judiciary Committee’s proposed bill should be read in light of the Judiciary Committee’s proposed but, apparently, rejected theory of bribery from the impeachment process. This proposed bill would transform the federal bribery statute into an open-ended method by which (former) presidents—and truly all federal elected officials—could be prosecuted for engaging in normal politics. If the president offers a person an official act in exchange for that person’s performing some official act, and that exchange indirectly benefits the president, then the president will have engaged in bribery. We table for now whether such a statute is constitutional. Instead, we contend that this bill would lead to undesirable policy consequences. The statute, if enacted, would in effect criminalize normal democratic politics.

This overly expansive redefinition of “bribery” is poor policy. The ultimate effect of this statute, if it were systematically enforced, would be to transform a partisan, party-leader and policymaking president into something more akin to a modern British monarch—a nonpartisan figure who is not allowed to publicly give voice to independent views about what measures advance the public good. Federal prosecutors, through the power of the criminal process, will dictate what that public interest is.

Consider an example. The president supports the passage of a statute as essential to the public good. He needs support for the bill in Congress. The president also believes passage of this bill equally essential for his reelection prospects. Here, the president acts with dual motives. (Blackman wrote about mixed motives in the context of obstruction of justice here.) In our hypothetical, a well-connected constituent of a member of Congress had been indicted by the Department of Justice. That member of Congress lobbies the president to pardon the constituent. The president then tells the member that he will pardon the member’s constituent, if the member supports the president’s bill. The constituent’s guilt or innocence is not central to the president’s decision-making. What is central to the president’s decision is the president’s conception of the public good: the passage of his bill, and his and his party’s reelection prospects. Analytically, we argue this exchange of an official act for an official act is not a bribe, because nothing was personally accepted.

Here, the president is offering one official act (the quid—the pardon) in exchange for another official act (the quo—the member’s vote). The president sincerely believes this element of his political program—that is, passage of the bill—will advance the public good as he conceives it. Likewise, the president expects to indirectly benefit from the member’s vote: He hopes his electoral and his party’s prospects will be improved. (However, there are a great number of indeterminate and intermediate factors that may lessen any such expected future benefit.) This exchange resembles congressional log-rolling: Members of Congress exchange one official act (that is, one member’s vote) for another official act (another member’s vote). One of the virtues of such log-rolling is that these acts are done in public: Votes are recorded, even if the negotiations behind the deals are private. Historically, such transactions have not been considered illegal. Under this new theory of bribery, these arrangements (that is, trading one official act for another official act) could be illegal.

Our criticism of this bill has limits. We agree that the president’s discretionary powers can be probed for alleged wrongdoing. We do not think that the president can redefine the “public good” to include conduct that has been traditionally understood to be bribery.

Our position is far more narrow. We draw a distinction between a suitcase full of cash and an exchange of one official act for another. The former provides the president with a wholly private benefit. He personally accepts the cash. The benefits flow entirely to the officeholder, and no commensurate benefit flows to the public at large. For that reason, such transactions are usually kept secret. In the suitcase-full-of-cash hypothetical, the interest of the public and the public official are not aligned.

However, the latter scenario—one official act exchanged for another official act—does not exclude the public from the expected benefits. Indeed, § 201(b)(2) makes it a crime when a public official accepts something of value “personally.” This statutory language reflects the traditional conception of bribery: Suitcases full of cash accepted personally by the wrongdoer are bribes. But changes in public policy or “official acts”—which are in no meaningful way “personally” accepted and are instead shared with the public at large—are not bribes.

Indeed, when one public act is swapped for another public act, the government officials are at least partly motivated by a public benefit. These sorts of transactions are frequently not made in secret. Indeed, the politician wants his base to know that he has actively pursued the “public interest” as he and they understand it. The officeholder will want to take credit for the expected public benefit. In almost all cases, these acts have to be made or, at least, consummated in public—for example, granting a pardon and voting on a bill. Here the interest of the public and the public official are substantially aligned.

Of course, as we noted in an earlier hypothetical, the public official will often have dual motives: He seeks to advance a contestable conception of the public good and also seeks to advance his and his party’s electoral prospects. Such dual motivations are a permanent feature in a democracy, where different views of the public good are allowed within the governing legal framework. Blackman described an important historical example in a New York Times op-ed, which the president’s counsel read from during the impeachment trial:

In 1864, during the height of the Civil War, President Lincoln encouraged Gen. William Sherman to allow soldiers in the field to return to Indiana to vote. What was Lincoln’s primary motivation? He wanted to make sure that the government of Indiana remained in the hands of Republican loyalists who would continue the war until victory. Lincoln’s request risked undercutting the military effort by depleting the ranks. Moreover, during this time, soldiers from the remaining states faced greater risks than did the returning Hoosiers.

Lincoln had [dual] motives. Privately, he sought to secure a victory for his party. But the president, as a party leader and commander in chief, made a decision with life-or-death consequences. Lincoln’s personal interests should not impugn his public motive: win the war and secure the nation.

In such situations, where dual motives are evident, the president and his parties’ supporters will naturally emphasize the public good or purposes the president sought to achieve. The president’s opponents will naturally emphasize partisan electoral, if not personal, motivations behind the president’s conduct. Any investigation, impeachment or indictment will only reveal what all know: The president, like all other elected officials, has contestable views about the public good. Not only that, all presidents are motivated, in part, by expectations of what policies will advance their personal and their party’s electoral prospects.

Not everyone will agree with the president’s understanding of the public good. But the president’s authority to define the public good springs from two sources. First, he is a citizen in a democracy where the meaning of the “public good” is a contestable concept. Second, he holds an elective office, within a party system, where the public knows he will be making discretionary policy judgments on imperfect information in real time. And prosecutors should not have the boundless authority to second-guess the president’s determinations merely because they conceive the public good differently. Alexander Hamilton described this concern in Federalist No. 65: A conviction, or even holding an investigation, will only reflect the “comparative strength[s]” of “pre-existing [political] factions” or competing contestable views of the public interest. These prosecutions would not be based on any neutral sense of justice or fair play in the political community, much less “real demonstrations of innocence or guilt.” It is the electorate that should assess the consequences of a politician’s purportedly acting in the public good, as he sees it, by exchanging official acts.

On Lawfare, Andrew Kent wrote that the president could be prosecuted for issuing a pardon “for personal reasons unrelated to the public good.” But Kent does not identify any mechanism for a federal prosecutor to determine what is in the public good. This concept of the public good is contestable and malleable. This difficulty is not unique to pardons but applies to all discretionary executive decisions taken by the president: for example, pardoning and investigating his own friends and confidants, and pardoning and investigating his opponents and their friends and confidants. There is no principled or rule-like way for the courts to monitor this political context. Indeed, there is no shared conception of what the public good is—especially in our polarized society. Recent Supreme Court decisions such as Kelly v. United States and McDonnell v. United States have cast further doubt on the power of prosecutors to draw the difficult line between legal political acts and federal offenses. Perhaps some critics of our approach may rely on the concept of “corruption” to draw the line. Under § 201, an element of bribery is that the exchange must be “corrupt.” But courts and commentators have long struggled about what the word “corrupt” might mean in circumstances other than the most traditional and obvious “suitcase full of cash” example. Our position is simple: Absent a traditional bribery charge with its concomitant suitcase full of cash, let the voters, not prosecutors, decide what is in the public interest.

There is another problem with this proposed bill. Bribery would not be not limited to actually taking a final, public act, such as issuing a pardon. Federal law would also prohibit an “attempt” to issue a pardon, as well as a “conspiracy” or agreement to issue a pardon. Under the new bill, it would now be illegal for the president to even discuss issuing such a pardon with his counsel. Those discussions could give rise to an attempted bribery charge. In every such situation, traditional protections of these sensitive discussions—deliberative process privilege and executive privilege—would give way to the crime-fraud exception. Presidents could no longer candidly discuss all aspects of politics because politics would have been criminalized. Attorneys are likely to be chilled in giving candid advice for fear of prosecution. This broad theory of bribery could even lead to prosecutions based on the president’s speeches to the public. Consider a hypothetical in which the president asks constituents at a political rally if they would support him at the polls if he pardons a specific person. Under the new theory of bribery, seeking legal advice and everyday political discourse would now be a crime.

Some readers may believe that our predictions are overwrought. We think the better view is that our predictions will merely extend a political and legal reality that has already deeply penetrated, almost unnoticed, into our body politic. When federal prosecutors decide whether to charge the president, they will be influenced by the president’s public and private opinions about contestable political issues. Under this approach to federal criminal law, the prosecutors will be compelled to investigate the president’s opinions, and it is likely they will determine whether those opinions are consistent with their understanding of the public interest. The very fact that such investigations of contestable matters of opinion are and will be conducted will necessarily chill presidential speech. Freedom of speech encompasses one-and-all: including presidents.

In 2017, Bob Bauer wrote on Lawfare about whether President Trump committed the crime of obstruction of justice. His analysis confirms our concerns. Bauer wrote:

[First,] [t]he president resents Jeff Sessions’s decision to recuse himself and says that he would not have nominated an attorney general who intended to follow the recusal rules in this case. [Second,] [the president] also doubts that he can trust Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, because he was U.S. attorney in a city, Baltimore, that is Democratic in its voting pattern. In neither case does the president seem to appreciate, or be moved by, the conception of professionalism, including independence and impartiality of judgment. And, of course, Trump’s continued emphasis on the supreme importance to him of loyal subordinates in the ranks of law enforcement will not serve him well as prosecutors form a picture of him in evaluating evidence of obstruction. (Emphasis added.)

Here Bauer is stating as fact what we are only predicting: that federal prosecutors will examine the president’s public views about political matters when deciding whether to charge him with obstruction of justice. Bauer is quite frank: The president’s “emphasis” about loyalty “will not serve him well” when prosecutors “evaluate evidence.” There is a stark difference between Bauer’s position and ours. We are profoundly troubled by such behavior. Prosecutors should not criminalize politics and undermine traditional American free speech norms. By contrast, Bauer is, at best, nonjudgmental in regard to such conduct by prosecutors. He might even agree that such prosecutorial conduct is not misconduct at all but is consistent with best practices. Let’s assume that Bauer is correct: Federal prosecutors will make charging decisions based on whether the president expressed the “wrong” opinions in public about politics. Or, in light of the Abuse of the Pardon Prevention Act, federal prosecutors will make charging decisions based on their conception of whether political horse-trading involving pardons advances the public good. Bauer has already signaled how this bill will be wielded by aggressive federal prosecutors. Our predictions are far from overwrought.

At bottom, this statute would effect a radical change in how the presidency is understood. Historically, the president has been viewed as an independent political actor, with democratic bona fides, who was charged with making discretionary policy judgments. Now, he would be transformed into a slow-moving, process-bound, “nonpartisan” actor.

Some readers may praise this change. But we do not think such a change is in the public interest. Of course, the public interest is always contestable because no one has the institutional knowledge or widely accepted power to declare a monopoly on what is in the common good. The president should be able to make important decisions with vigor, independence and dispatch. This proposed bill would alter the presidency such that he would now second-guess his official actions for fear of prosecution. Federal prosecutors should not be authorized to dictate what is in the public interest.

Many people who read this bill may not realize its likely consequences. Others can foresee these consequences, and approve of them, because they seek to transform the presidency. All should recognize that the consequences of this bill, if enacted, will extend far beyond President Trump, or even a President Biden. The presidency has far less to fear from this bill than the 535 members of Congress would. Indeed, our concerns apply more forcefully to Congress, which does not control the apparatus of federal prosecution. In December 2019, we wrote:

Consider a third hypothetical in which personal and public motivations are inextricably intertwined. Two members of Congress are engaged in negotiations about a bill. Each agrees to support the bill only after it is amended to provide $1 billion in additional spending in their respective districts. They each have mixed motives. First, they believe that the extra $1 billion will help improve the welfare of their districts—which is part of the public good, as they conceive it. Second, they understand that bringing home the bacon will help their reelection campaigns. “All politics is local,” the old adage goes. The run-of-the-mill horse-trading described in this example might be bad policy and, arguably, is a misuse of discretion. But whatever else it is, it is not bribery.

If we’re wrong, almost every member of Congress could be indicted under the federal bribery statute. Indeed, if every such deal or compromise is a presumptive crime, then the Department of Justice will have the power to investigate every set of political compromises that accrue on nearly all major spending bills. Such a theory of bribery would allow the department to investigate, and later indict and seek to convict, members of Congress involved in political compromise and log-rolling.

We should resist efforts to criminalize politics. The Abuse of the Pardon Prevention Act may seem like a prudent idea in the current moment. But the bill criminalizes normal politics; it will end with criminalizing political speech. Do critics of the current president really want to give Attorney General William Barr the power to prosecute congressional log-rolling? Be careful what you wish for.