Accountability for the Syrian Regime: An Overview

While the conflict has subsided in most areas of Syria after nearly eight years of war, violence has escalated in the northwestern part of the country. The Idlib region is the last remaining area held by anti-regime forces and part of a demilitarized zone created in an agreement between Russia and Turkey in September 2018.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

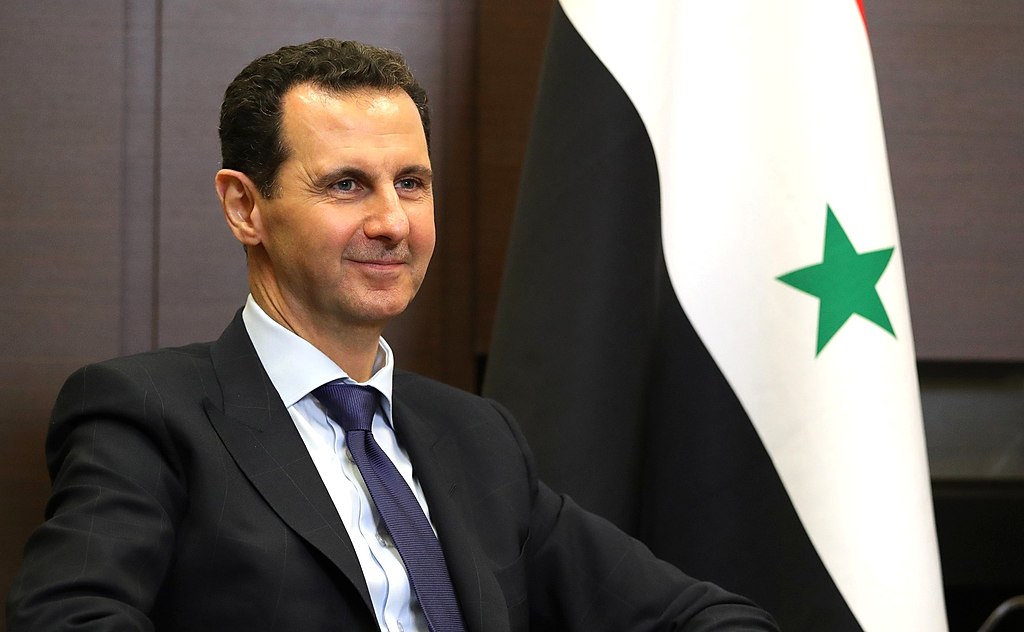

While the conflict has subsided in most areas of Syria after nearly eight years of war, violence has escalated in the northwestern part of the country. The Idlib region is the last remaining area held by anti-regime forces and part of a demilitarized zone created in an agreement between Russia and Turkey in September 2018. Although the agreement brought a temporary reprieve in fighting, the situation deteriorated quickly over the past two months. Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, a militant Islamist group with links to al-Qaeda, has gained dominance over the other opposition groups in the region and pro-government forces have scaled up their attacks. Most recently, on Feb. 18, a “double-tap” bombing in Idlib city killed at least 17 and wounded 70 others. Amidst this escalating violence, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad visited Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and President Hassan Rouhani in Tehran this week in one of his first known foreign visits since the war began. During the visit, Assad thanked the Iranians for their support throughout the war, without which, along with Russian backing, he likely would not have succeeded, and Rouhani reaffirmed Iran’s willingness to “stand by Syria.”

Despite these developments, the European Union and the U.S. are still working to hold the Syrian government accountable. In fact, over the past six months, significant progress has been made in the direction of justice and accountability for the crimes committed by the Syrian regime and actors that support it. This post provides an overview of the most recent efforts—through domestic national proceedings and sanctions—of holding individuals and corporate actors accountable for those crimes.

Universal Jurisdiction Cases in Europe

As Hayley Evans explored recently on Lawfare, European courts, especially those in Germany and France, currently seem to offer the best hope for accountability for international crimes committed in Syria. While these accountability efforts have been slow and fragmented over the past few years, progress toward holding high-level Syrian government officials accountable has accelerated over the past month. This recent progress includes:

- In June and November 2018, Germany and France, respectively, issued international arrest warrants for senior Syrian officials, including the head of Syria’s Air Force Intelligence Directorate, Jamil Hassan, for their alleged involvement in torture, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

- On Feb. 12, Germany’s police force arrested two former high-ranking members of the Syrian General Intelligence Directorate allegedly involved in crimes against humanity, torture and murder. See Hayley Evan’s post for more details on this case.

- Also on Feb. 12 and as part of a joint investigation with Germany, French authorities arrested another employee of the Syrian intelligence department allegedly involved in committing torture, crimes against humanity and war crimes between 2011 and 2013. The arrests in France and Germany marked the first time that western prosecutors had arrested individuals allegedly responsible for atrocities committed on behalf of the Syrian government.

- On Feb. 17, Germany reportedly asked the Lebanese government to extradite Jamil Hassan while he was seeking medical treatment in Lebanon. Although the German prosecutors have not confirmed the story, this move would signal that they did not issue the June 2018 arrest warrant for its symbolic value.

- Finally, on Feb. 19, nine torture survivors from Syria working closely with several civil society organizations filed a criminal complaint in Sweden against 25 known and further unknown high-level officials of the Syrian security regime. The nine plaintiffs were detained in 15 different facilities around Syria at different points between February 2011 and June 2015. This criminal complaint is part of a series of complaints that have been filed by Syrians throughout Europe and that led to the opening of investigations in Germany, France and Austria. Sweden, like Germany, can exercise universal jurisdiction over individuals even when there is no link between the country and the crime. In fact, the first judgment against a former soldier of the Syrian Army was issued in Sweden in September 2017. He was sentenced to eight months in prison for violating human dignity by posing with his boot on a corpse.

These recent achievements are the result of two different approaches to investigations and arrests adopted by European prosecutors. As Andreas Schüller, director of the International Crimes and Accountability Program at the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), explains, the landscape of universal jurisdiction consists of the “no safe haven” approach, where you “prosecute those you find on your territory,” and the “global enforcer” approach, which is “a more strategic way of gathering evidence for arrest warrants against high-level perpetrators, like state actors.” The former has resulted in a number of prosecutions of low-level individuals involved with nonstate armed groups in Syria and the three latest arrests in Germany and France (see here for a collation of some of these proceedings). The latter has resulted in the structural investigations in Germany and France, the international arrest warrants issued in 2018 and the recent extradition request.

Accountability in U.S. Courts: Marie Colvin Case

Although the U.S. has not yet opened any relevant criminal proceedings, it is worth mentioning the civil suit that recently resulted in a judgment against the Assad regime. As discussed previously on Lawfare, a complaint against the Assad regime was filed in July 2016 in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia for the murder of the prominent war correspondent Marie Colvin. On Jan. 30, in response to the plaintiffs’ motion for default judgment, the court found the Syrian government liable for the extrajudicial killing of Colvin and entered judgment in the amount of $302 million.

The evidence submitted on behalf of the plaintiffs provides an important overview of the policies and practices of the regime and its systemic suppression of the media (see here for more analysis). The court explained that the evidence “shows that officials at the highest level of the Syrian government carefully planned and executed the artillery assault on the Baba Amr Media Center for the specific purpose of killing the journalists inside.” In addition to producing useful evidence for other cases moving forward, this judgment demonstrated that the Syrian government will bear legal responsibility for its crimes.

Corporate Accountability

Accountability mechanisms are also looking to the economic actors that fuel and profit from the behavior of the Syrian government and other armed groups. In June 2018, in the most novel and well-known case, the French cement firm Lafarge was charged with complicity in crimes against humanity for paying the Islamic State and other nonstate armed groups millions of dollars to keep a factory open in northern Syria throughout the conflict. The case against Lafarge is reportedly the first time a parent company anywhere in the world had been charged with complicity in crimes against humanity.

Other corporate accountability cases involve investigations and charges against companies that have breached sanctions. Most recently, the Antwerp Criminal Court on Feb. 7 convicted three Flemish companies for shipping 168 tons of isopropanol with 95 percent purity to Syria between 2014 and 2016 without submitting the requisite export licenses (an export license for isopropanol 95 percent is mandatory under the EU’s 2013 sanctions on Syria). Isopropanol is a critical ingredient in the nerve agent sarin, and, according to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, isopropanol was detected in the sarin used in the deadly 2017 attack in Khan Shaykhun. The Antwerp court imposed a conditional fine of up to 500,000 euros on the three companies and conditional prison sentences for one managing director and one manager.

Over the past few years there have also been investigations of and punitive measures taken against companies involved in developing surveillance systems for the Syrian government. Early on in the conflict, an Italian company, Area S.p.A., sold network-monitoring equipment from the U.S. to Syria without authorization from the U.S. government. In 2014 the company paid a $100,000 civil penalty to the U.S. government for that shipment, and in 2016 its offices were raided by Italian authorities as part of an investigation into a possible breach of European law for that same shipment. A French software components company, Qosmos, has also been under investigation for its alleged sale and installation of a large-scale electronic communication surveillance system for the Syrian government. In 2015 a French court declared the company an “assisted witness” for its possible complicity in acts of torture committed in Syria. According to the International Federation for Human Rights, which filed the initial complaint against Qosmos, the term “assisted witness” constitutes an important step forward in a case and may precede an indictment.

Sanctions

Meanwhile, both the U.S. and the EU continue to implement sanctions against the Assad regime and its supporters, with a particular focus on preventing reconstruction projects. In the U.S., new sanctions have been introduced as part of the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act, which recently passed in both the House and the Senate and received support from the White House. The legislation is named in honor of the former Syrian military photographer “Caesar,” who smuggled evidence of systematic torture and killings out of the country. Notably, the act will impose new sanctions on anyone, including foreign individuals and firms, that “knowingly, directly or indirectly, provides significant construction or engineering services to the Government of Syria.” By definition, these sanctions will also extend to Russian and Iranian firms.

These additional sanctions coincide with new sanctions imposed by the EU in January on eleven business executives and five associated companies. With this round of sanctions, the EU specifically targeted individuals and entities with ties to the regime’s flagship reconstruction project, Marota City. (See here for an explanation of why these reconstruction projects may have a devastating impact on millions of homeless or displaced Syrians.) The Caesar sanctions will likely also target these actors.

While some governments and companies, particularly in the Persian Gulf, are moving to restore relations with the Syrian government and take advantage of new economic opportunities, these sanctions provide an important affirmation that the U.S. and the EU will not support Assad’s reconstruction efforts and will take punitive measures against those that do. The question for these sanctions, as with all of the other accountability measures, is whether they will have a true positive impact or whether they will merely precipitate further harm to the victims of the regime.

-(1).png?sfvrsn=fc10bb5f_5)