Al-Qaeda After Ayman al-Zawahiri

Despite rumors of bin Laden's successor's death, the organization remains resilient.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: The status of al-Qaeda, once the top terrorism threat to the United States, is in doubt, with many analysts questioning the group’s strength. The possible death of its leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, has made these questions even more pronounced. Tore Hamming of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation at King’s College argues that al-Qaeda remains potent and that its leadership in particular remains strong, even if al-Zawahiri has died.

Daniel Byman

***

Al-Qaeda has never really been as weak as it has often been portrayed. Many observers believe al-Qaeda does not present a critical terrorism threat in the West; they argue that its key leaders have been killed one after the other, that it was overtaken by the Islamic State, and that its global network has suffered from sustained counterterrorism pressure and internal competition and conflict. But all along, it has remained relevant, expanded its military campaigns in several countries, and maintained a resilient organizational structure filled with senior leaders with years of experience.

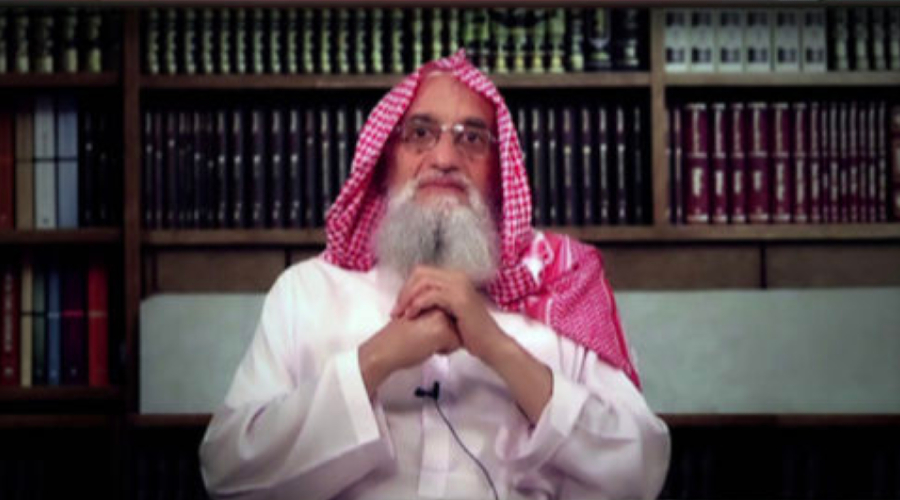

In November 2020, rumors spread that al-Qaeda’s longtime leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, had died from illness, leaving the group with no apparent heir. Al-Qaeda’s senior leadership has yet to confirm the news, but al-Zawahiri has not issued a statement that would debunk it, either. The organization may now be in the midst of a transition that calls for an accounting of al-Zawahiri’s tenure and his potential successors.

Taking Stock of al-Zawahiri’s Accomplishments

Al-Zawahiri has been a target of criticism ever since taking over the leadership of al-Qaeda from Osama bin Laden, ridiculed by both “friends” and foes. The typical points of condemnation are that he lacks bin Laden’s charisma, is out of touch, does not control al-Qaeda’s local affiliates, and does not have a clear strategy.

But judged on how he has managed the al-Qaeda network over the past six years, from the immediate aftermath of the break with the Islamic State until now, al-Zawahiri’s tenure as amir of al-Qaeda has been quite successful. The trajectory in Syria involves obvious failures, as he was unable to prevent the organizational split with the Islamic State, the escalation of jihadi infighting, and the disobedience of Abu Muhammad al-Julani, who withdrew his Syria-based organization’s al-Qaeda affiliation. Yet, faced with an enormous challenge from the Islamic State and the powerful symbolism of its declaration of a new caliphate, he managed to prevent al-Qaeda’s global network from imploding and retained the allegiance of al-Qaeda’s remaining affiliates. Events have shown that the bond of loyalty he has from al-Qaeda veterans is tremendously strong, as they continuously praise and protect him when he is facing criticism. He does not receive sufficient credit for keeping the network cohesive in such challenging times.

Al-Zawahiri’s most pressing problem has been his inability to communicate regularly with senior aides and affiliates. At times, this has left him out of touch and with little influence. This was particularly the case with regard to Syria in 2015 and 2016. During this period, Jabhat al-Nusra initiated a process to detach itself from al-Qaeda, with al-Zawahiri unable to affect events, and in October 2015 he eulogized Abu Humam al-Shami, at the time a senior al-Nusra official who it was later revealed was alive and now heads al-Qaeda’s Syrian franchise, Hurras al-Din. Easing the negative impact of his isolation, however, al-Zawahiri has been supported in his management of al-Qaeda by the hub of senior officials in Iran. These leaders have functioned as liaisons between militants in Syria and al-Zawahiri, just as they have instructed other al-Qaeda affiliates around the globe. The importance of this group of leaders, constituting what al-Qaeda calls the Hittin Committee (likely named after the place where Salahuddin fought the Crusaders for control of Palestine), is hard to overestimate and a sign of institutional strength.

The Next in Line

After weakening the Islamic State in the Levant, the United States and other state forces are once again doing their best to eliminate al-Qaeda’s leadership. In recent years, they have killed:

- Hamza bin Laden, Osama bin Laden’s son and potential heir

- Asim Umar, head of al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent

- Hossam Abdul Raouf, shura council member and senior media official

- Zakir Musa, head of Ansar Ghazwat al-Hind

- Qassim al-Raymi, head of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

- Yahya Abu Hammam, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’s amir in the Sahel

- Abu Yahya al-Jaza’iri, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’s amir in the Sahel

- Abdelmalek Droukdel, head of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb

- Abu Muhammad al-Sudani, general administrator of Hurras al-Din

- Abu Khadija al-Urduni and Abu al-Qassam, shura council members of Hurras al-Din

However, much of al-Qaeda’s leadership remains intact and new figures have filled in the ranks. The organization’s resilience has been aided by a strategic safe haven.

In one of his last speeches as secretary of state, Mike Pompeo emphasized the role of al-Qaeda’s leaders in Iran and the threat they pose. That several high-ranking al-Qaeda leaders and officials are based in Iran is nothing new. Over time, Iran has shifted from imprisoning officials to imposing house arrests, and more recently, al-Qaeda leaders based in Iran have appeared to roam freely in the country or have managed to leave. Osama bin Laden’s son, Hamza, was released from Iran in 2010 and traveled to Pakistan to reunite with his father, and in 2015, five senior leaders were released as part of a prisoner exchange and traveled to Syria. Another senior leader—Abu Muhammad al-Masri, al-Qaeda’s second in command—was killed by Israeli special forces on a street in Tehran in August 2020.

In Iran, this cohort has enjoyed a life free from the threat of drone strikes and, as confirmed by Abu al-Qassam, a senior figure who traveled from Iran to Syria, with only minor restrictions. This enabled close and ongoing communication with loyalists in Syria and other places where coordination would have been more challenging, if not impossible, from the Afghanistan and Pakistan region. Al-Qaeda’s presence in Iran could potentially turn into a problem if al-Zawahiri’s successor is chosen from among the veterans based in the country. Iran would have significant leverage on al-Qaeda’s amir and be likely to impose restrictions on him. This would not only limit his control over the group but also make al-Qaeda vulnerable to criticism from rival jihadis who would use it to discredit the group.

In addition to the leaders of al-Qaeda’s various affiliates, the group still has a large number of senior and veteran commanders, officials, and ideologues at its service. Several of these could be potential contenders for al-Zawahiri’s successor.

First and foremost among them is Saif al-Adl, a veteran Egyptian commander who recently succeeded al-Masri as al-Qaeda’s number two. Known for being the head of al-Qaeda’s most powerful institution, the military council, for a period starting in 2001 and the person who convinced Osama bin Laden to give a chance to the bully Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, al-Adl has a long history in al-Qaeda’s most senior circles. He is the obvious candidate to replace al-Zawahiri not only because of his formal position as his deputy but also because of the respect he commands within the global al-Qaeda network. In recent years, he has been highly active from his Iranian safe haven, engaging with al-Qaeda loyalists in Syria and occasionally issuing directives through Telegram. Should he replace al-Zawahiri, he would likely relocate out of Iran.

Abd al-Rahman al-Maghribi is another senior figure and shura council member. Originally from Morocco, he is trained as a computer engineer and married to one of al-Zawahiri’s daughters. For many years, he has been heading al-Qaeda’s media operations and its primary media institution, al-Sahab. Already in 2010, al-Maghribi was acting as a key al-Qaeda member in Iran, updating bin Laden on the affairs of group members in the country. As with al-Adl, sources told the author that al-Maghribi has remained active in Iran running the group’s global media efforts, including giving directions to al-Qaeda’s regional media outlets. One of al-Maghribi’s aides in Iran is Qattal al-Abdali, a Saudi national and veteran al-Qaeda official, who is assisting in running the al-Qaeda media structure.

Heading al-Qaeda’s organizational duties in Iran is Yasin al-Suri and his likely deputy, Adel al-Wahabi al-Harbi. Al-Suri has for many years been in charge of facilitating the transit of money and personnel in and out of Iran, interrupted only by a brief stint in prison. With Iran as the organizational epicenter of al-Qaeda, al-Suri’s role is likely greater than previously assumed. Closely affiliated with al-Suri, Abu Hamza al-Khalidi, originally from Saudi Arabia and a member of al-Qaeda since 2007, is believed to have functioned as a central link between al-Qaeda’s global affiliates and the network’s leaders in the Afghanistan and Pakistan region and Iran, in a role resembling that of general manager. Early in his al-Qaeda career, al-Khalidi was identified as part of a new generation of leadership that al-Qaeda was grooming to take more senior roles in the future, and he is now rumored to be heading al-Qaeda’s military council, having taken over from Saif al-Adl.

After being freed from captivity in Iran in 2015, Abu Abdul Karim al-Khurasani migrated to Syria, where he is now the most senior al-Qaeda figure after the death of Abu Muhammad al-Sudani. Al-Khurasani’s precise role in Syria is unknown, but it is believed that he has not taken up a role in the local affiliate, Hurras al-Din, and instead likely functions as al-Qaeda’s representative in Syria. Since late 2017, he has headed several reconciliation initiatives between Hurras al-Din and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which is indicative of his standing in jihadi circles.

On the ideological side, veteran ideologue Abu al-Walid al-Filastini is believed to still be alive. Raised in Saudi Arabia, Abu al-Walid left Saudi Arabia for Peshawar in 1986. He spent the late 1990s in London, where he was deputy to prominent radical cleric Abu Qatada al-Filastini. The most recent news about Abu al-Walid is that he was released from prison in Pakistan in 2017 and relocated to Turkey, where another senior al-Qaeda veteran, Mohammed Islambouli, is also present, among others.

Besides the wealth of operational veterans, al-Qaeda appears to have a well-functioning shura council. Dominated by Egyptians, the advisory council has remained active in recent years—a sign of institutional strength despite years of counterterrorism efforts.

Still Going Strong

Al-Qaeda supporters do not fear the day al-Zawahiri is no longer around. As with bin Laden’s death, they do not see the future of the group as dependent on a single individual, and with a plethora of seasoned leaders around, they feel confident that al-Zawahiri’s successor will be capable of leading the group. Besides the older guard of veterans, a new generation of leadership is being groomed for future leadership positions. Many have been killed in previous years, but not all. This generation has matured during a particularly challenging period and gained experience on the battlefield. Despite years of war, assassinations, and isolation, al-Qaeda’s leadership remains resilient and prepared to weather further shocks.