America's Counterterrorism Allies: What Are They Good For?

Editor's Note: The United States cannot fight terrorism without allies, but these alliances bring with them new problems and at times make counterterrorism far more complicated, to put it gently. Clint Watts, a leading terrorism analyst and fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, argues that many of these relationships are more trouble than they're worth. The U.S. relationship with Egypt, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia in particular, he contends, needs to be reevaluated, while the United States should double down on relationships with countries like Jordan and Tunisia.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor's Note: The United States cannot fight terrorism without allies, but these alliances bring with them new problems and at times make counterterrorism far more complicated, to put it gently. Clint Watts, a leading terrorism analyst and fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, argues that many of these relationships are more trouble than they're worth. The U.S. relationship with Egypt, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia in particular, he contends, needs to be reevaluated, while the United States should double down on relationships with countries like Jordan and Tunisia.

***

America’s allies have come under intense scrutiny this election season. The Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump, postulated at times that he might, if president, break long-standing alliances with NATO. His premise: America’s allies aren’t paying their share of the burden in fights around the world. Trump’s call for reexamining alliances to better understand what return Americans get on their investments has merit but focuses in the wrong direction. He has taken European allies to task while giving America’s counterterrorism allies in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia a pass. The preponderance of U.S. alliances in recent years have not been through traditional Cold War agreements but instead through ad hoc arrangements to pursue al-Qaeda and its later spawn, the Islamic State.

Over the last fifteen years, the U.S. has partnered with dozens of countries, providing military assistance and cooperation for targeting terrorists or building partner capacity or, in some cases, foreign aid to mitigate the root causes for terrorism. The results of these partnerships have been uneven at best. Tactical gains against specific terror targets have, in many cases, been offset by long run strategic divergence between the U.S. and its counterterrorism allies. Some alliances often put the U.S. in a twist both internationally and domestically. Just this month, President Obama, attempting to preserve a counterterrorism ally, vetoed a bill authorizing U.S. citizens to sue Saudi Arabia for perceived complicity in the 9/11 attacks – a veto overridden by Congress.

Moreover, the cross-cutting, ad hoc development of counterterrorism alliances have put America at odds with other state partners while simultaneously confirming the grievances of terrorists. The current U.S. fight against the Islamic State provides a prime example. The U.S. decision to lead the fight against the Sunni Arab Islamic State has resulted in a) support to an Iraqi Army backed by Iran with whom the U.S. conducts nuclear negotiations that agitate Sunni partners; b) partnering with Kurdish forces while simultaneously allying with their enemy, Turkey, for airbases; c) working with Saudi Arabia while they pursue a sectarian conflict against Yemen’s Iranian-backed Houthis and inflame sectarianism throughout the Middle East; and d) negotiating, partnering and then breaking off cooperation with Russia while they undertake airstrikes on Syrian civilians. Aside from the contradictory implications in fighting the Islamic State, the U.S. counterterrorism approach has established enduring alliances with nations that have also been sources of terrorism – namely Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. These three so-called essential partners in America’s counterterrorism operations, it could be argued, also represent the three largest fountains of jihadi terrorism over the past thirty years. Here’s a quick snapshot of these three contradictory relationships.

The preponderance of U.S. alliances in recent years have not been through traditional Cold War agreements but instead through ad hoc arrangements to pursue al-Qaeda and its later spawn, the Islamic State.

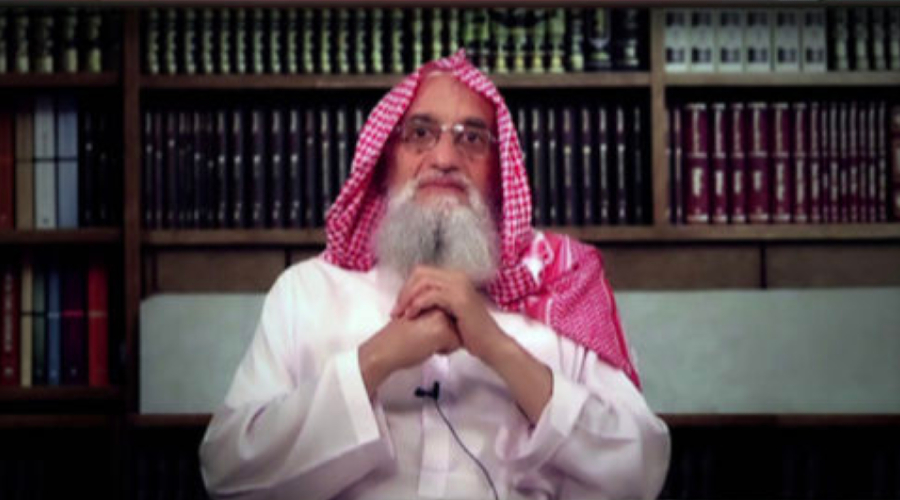

During the 1980s, the U.S. developed a close relationship with Pakistan while supporting the Afghan mujahideen against the Soviet Union. After the September 11, 2001 attacks, Pakistan’s relationship with the Taliban brought into question their complicity with al-Qaeda. Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage reportedly strong armed Pakistan into joining the American counterterrorism fight, warning its intelligence chief, “'Be prepared to be bombed. Be prepared to go back to the Stone Age'” if it didn’t cooperate with America. Pakistan ostensibly complied and has continued receiving billions of dollars in military assistance and foreign aid, yet appears at almost every turn to be playing a double game. As an ally against al-Qaeda, Pakistan served as the operational base for Lashkar-e-Taiba’s attack on Mumbai in 2008, conducted sporadic and largely ineffective military operations into its tribal areas to root out al-Qaeda support, teed up drone targets preferable to their interest while hypocritically backing protests against U.S. drones strikes, have not found a now elderly Ayman al-Zawahiri, and for years failed to find Osama Bin Laden residing less than a mile from their military academy.

Saudi Arabia likely represents the most confusing American counterterrorism alliance. The U.S. came to the Kingdom’s aid when Iraq threatened the country in the early 1990s. American blocking of Iraqi aggression resulted in U.S. presence in Saudi Arabia accentuating grievances that fueled al-Qaeda – which later aimed 15 Saudi citizens at the U.S. on September 11, 2001. Following the attacks, the U.S. quickly allied with Saudi, who bloodily purged al-Qaeda from their country while domestically fanning the flames of Wahhabi ideology fueling the fire of jihadi angst against the U.S. and Israel. Angry Saudi boys raised by this militant scripture have been the largest percentage of foreign fighters to al-Qaeda in Iraq last decade and the Islamic State this decade. Although a U.S. counterterrorism partner, the Kingdom has beheaded more people than the Islamic State and, today, mercilessly bombs civilian targets in Yemen that kill scores of innocent people and further incentivize support for local terrorist groups antagonistic to the U.S. Today’s U.S.-Saudi alliance appears to be playing again into the enduring ideology of Bin Laden and al-Qaeda, who justified targeting of the U.S. (its Far Enemy) to break support for Middle Eastern dictatorships (its Near Enemy).

U.S. payments and military hardware have traveled to Egypt for more than thirty years as a result of a 1979 peace treaty with Israel. During this period, the Egyptian government has aggressively quashed internal dissent radicalizing large groups of young men who formed many of the first Sunni jihadi groups. Egyptian abuse and imprisonment of jihadis incubated the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, which later merged with al-Qaeda. Unsurprisingly, an Egyptian, Mohamed Atta, served as a key leader for the 9/11 attacks. Egypt partnered with the U.S. after 9/11 and reclaimed citizens captured around the world. Egypt, after Tunisia, triumphantly overthrew President Mubarak during the Arab Spring of 2011, leaving the U.S. to delicately support a democratic uprising while endangering its counterterrorism needs. The fall of Mubarak renewed a separate extremist fringe contrary to American interests, the Muslim Brotherhood. The U.S. turned a blind eye in 2013 when the Egyptian military overthrew President Morsi. Apparently America was more worried about a rising Islamic State in the Sinai than sustaining a democratically elected government in Egypt. Today, U.S. counterterrorism cooperation with Egypt has made strides against the Islamic State, but the short-term gains likely won’t compensate for the returning view of America as a sponsor of Egyptian oppression – creating sympathies for extremist violence in Egypt and encouraging disenfranchised men to join regional al-Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates targeting the West.

Aside from the contradictory implications in fighting the Islamic State, the U.S. counterterrorism approach has established enduring alliances with nations that have also been sources of terrorism – namely Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt.

Counterterrorism alliances leave the U.S. in a difficult quandary. America doesn’t want to do major military deployments and nation building across dozens of failed and failing Middle Eastern and North African states where terrorists hide. The U.S. needs countries like Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt in the immediate term to squash jihadis intent on striking the West. Over the longer term, however, these counterterrorism alliances undermine U.S. national security interests, enflaming longstanding terrorist grievances and stymying larger U.S. strategic priorities and national security interests. Moving into the next administration, the U.S. should reassess its counterterrorism allies systematically, addressing the cost and benefit of each alliance.

In the near term, problematic counterterrorism partners like Pakistan, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia should be put on notice – assistance is no longer unconditional. Dr. Dafna H. Rand and Dr. Stephen Tankel’s recommendations in their report, “Security Cooperation & Assistance: Rethinking The Return On Investment,” provide essential guidance for U.S. counterterrorism alliances beyond 2016. They note that, “clearly identifying the goals of a particular security assistance and cooperation initiative, the time frame for achieving them, and agreed-upon metrics and methods for evaluating outcomes is essential in support of broader national security policy.” Beyond prioritizing objectives, U.S. counterterrorism efforts should understand the tradeoffs with partnerships, establish leverage in these relationships, and identify and apply foreign aid and military assistance under spelled out conditions. If counterterrorism partners cross-specified thresholds, say by committing human rights violations or oppressing minorities in pursuit of terrorists, then alliances should be ended.

Over the long term, the U.S. must identify its national security interests beyond simply counterterrorism. In all three alliances noted above, larger, perceived, and competing U.S. national interests result in counterterrorism relationships with countries that don’t share U.S. principles, values and goals. The U.S.-Egyptian partnership remains principally about maintaining Arab peace with Israel. Pakistani stability and nuclear threats to India routinely overtake counterterrorism priorities. Saudi historical dominance over oil markets sustains an enduring relationship with the U.S. In each of these alliances, the U.S. has committed indefinitely to countries that may fear a mutual threat but maintain different priorities and adhere to wildly different principles. Counterterrorism has also become profitable for many counterterrorism partners, particularly in the case of Pakistan. As noted a decade ago in the Combating Terrorism Center’s report, Harmony and Disharmony, lightly pursuing terrorists for America and yet never completely eliminating the terrorist threat brings in sizeable, steady revenue to counterterrorism partners.

Over the long term, the U.S. must identify its national security interests beyond simply counterterrorism.

The next administration should seek from the outset to establish clear constraints and expectations for troublesome counterterrorism allies. Foreign aid and military assistance will only come by pursuing counterterrorism in line with American principles in pursuit of U.S. objectives. By clearly and publicly establishing boundaries on counterterrorism partnerships, America can break its alliances for cause, without appearing to abandon allies for no reason – a common criticism of the U.S. in recent years. Short of breaking alliances, the U.S. could provide less assistance to dysfunctional counterterrorism partnerships. As Dan Byman noted in his recent article, US Counterterrorism Intelligence Cooperation With The Developing World And Its Limits, “a typical U.S. government response (to underperformers) is to provide allies with more aid in order to induce (bribe) them to do more.” But providing “more aid or exercising control vests more of the U.S. government in the relationship both politically and bureaucratically and may actually decrease U.S. leverage.” If the U.S. doesn’t divorce the ally entirely, they should at least reduce the flow of aid to reassert their leverage in the partnership.

Moving forward, the U.S. should do what it must for the safety of Americans in the near term, but over the longer term, reinforce counterterrorism relationships with partners that have mutual threats, shared objectives, and currently or may in the future share U.S. democratic values. This has been the method by which enduring and, contrary to Donald Trump’s assertion, beneficial alliances have occurred with European allies. Two counterterrorism partner countries the U.S. might consider prioritizing above its more fickle partners are Tunisia and Jordan. As the inspiration for the Arab Spring, Tunisia likely represents the best hope for democracy in North Africa, faces a stiff terrorist challenge, and needs U.S. counterterrorism assistance immediately. Jordan has been one of the most essential U.S. counterterrorism partners since 9/11, faces a massive refugee problem from Syria, and yet may come to embrace many democratic reforms before other countries in the region. Fifteen years after the September 11 attacks, the U.S. is and will be more dependent on counterterrorism allies. Victory over terrorists will ultimately come by having better allies rather than many allies.