Amnesty Flags Possible Spyware Abuse in Indonesia

The latest edition of the Seriously Risky Business cybersecurity newsletter, now on Lawfare.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: This newsletter is part of a collaboration between Lawfare and Risky Business. You can find the full version of the Seriously Risky Business newsletter and previous editions on news.risky.biz.

Amnesty Flags Possible Spyware Abuse in Indonesia

The burgeoning use of spyware in Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, presents risks to human rights, according to Amnesty International.

An Amnesty International report released at the beginning of May describes how Indonesian entities procure surveillance technologies through what it calls a “murky ecosystem of surveillance suppliers, brokers and resellers that obscures the sale and transfer of surveillance technology.”

Amnesty International and media collaborators including Haaretz and Inside Story used open-source intelligence such as commercial trade databases and spyware infrastructure mapping to find:

numerous spyware imports or deployments between 2017 and 2023 by companies and state agencies in Indonesia, including the Indonesian National Police (Kepala Kepolisian Negara Republik) and the National Cyber and Crypto Agency (Badan Siber dan Sandi Negara). As this research shows, several of these imports have passed through intermediary companies located in Singapore, which appear to be brokers with a history of supplying surveillance technologies and/or spyware to state agencies in Indonesia.

When it comes to infrastructure mapping, Amnesty International says it:

performed continuous internet scanning and network measurements to identify the deployment of attack servers and other infrastructure linked to highly invasive spyware. Spyware infrastructure from all different spyware vendors each have distinct fingerprints on how web servers are enabled, the locations where internet domains are purchased and how intermediary servers are set up. This has allowed Amnesty International to build visibility into the testing and deployment of spyware systems in multiple countries around the world. This methodology has also, at times, allowed for the identification of spyware backend systems deployed on networks, by linking the spyware infrastructure networks to a specific government in a country, but not to a specific agency. These technical measurements provide insights into the deployment of such spyware systems. In the case of Indonesia, the network measurements have been used extensively to confirm findings first identified in trade data.

The vendors identified include “Q Cyber Technologies (linked to NSO Group), the Intellexa consortium, Saito Tech (also known as Candiru), FinFisher and its wholly-owned subsidiary Raedarius M8 Sdn Bhd, and Wintego Systems.” Some of these vendors, such as NSO Group, Candiru, and Intellexa, have been sanctioned by the U.S. government because their products posed national security risks and had been involved in human rights abuses.

The report describes Indonesia as a case study on the “opaque sale and transfer of several highly invasive spyware tools.” Indonesia is the world’s fourth largest country by population. Amnesty International says these tools “are inherently incompatible with human rights and should be permanently banned.”

Amnesty concedes, however, it has “little visibility into who was targeted” with these systems, so it cannot say that these tools were used to target civil society. However, in mapping malicious domains associated with these spyware platforms, the group found “domains that mimic the websites of opposition political parties and major national and local news media outlets, including media from Papua and West Papua with a history of documenting human rights abuses.” The existence of these domains suggests, but does not definitively prove, repression.

And an Amnesty International report from 2022 documents how civil rights in Indonesia have increasingly come under threat.

Gatra Priyandita, an Indonesian foreign policy and cyber politics expert at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, told this newsletter that it was a “fair assessment” that Indonesian civil liberties had been in decline.

He told us that spyware had been used for legitimate national security purposes, such as in the fight against terrorism. However, he added, “there have been plenty of news stories and anecdotes about the security apparatus misusing them to spy on journalists, major opposition figures, and civil society activists.”

Priyandita didn’t think that the ability to acquire commercial spyware was causing a decline in civil liberties, so much as it was part of a broader trend.

He said “the quality of Indonesian democracy has been in decline for over 10 years now.”

“While Indonesian elections are free and fair, political elites, oligarchs, and members of the security apparatus have been known to also misuse their power to try to silence critics, often by accusing them of online defamation.”

“Since Indonesia’s democratic reform [Ed: in 1998], members of the national security, political, and business elite have been either misusing legal instruments or co-opting law enforcement to clamp down on criticism and dissent.”

But although spyware is just one more method of potential repression, Priyandita thinks it “definitely makes it easier and more attractive for officials to abuse power.”

He cited the Red White Command, an elite task force set up within the national police ostensibly created to deal with serious crimes such as narcotics trafficking and gambling rackets. It was, however, “co-opted by the political elite to harass individuals who threaten vested political or police interests[,]” and a report claims it controlled wiretapping and hacking capabilities.

The “good” news is that the Red White Command was disbanded after its head murdered one of his own officers.

Cracking down on uncontrolled exports of spyware is part of the solution. Amnesty’s report points out that Singapore appears to be a nexus and that several Indonesian spyware purchases were brokered by firms at least nominally located in the country.

But liberal democracies also need to convince governments to behave better in the first place.

Hospitals Push Back on Proposed Cybersecurity Penalties

American hospitals are resisting a U.S. government push to tie payments to meeting “essential” cybersecurity standards, while the government argues that more robust measures are needed because of recent health care sector incidents.

The Record reported that at the RSA conference this week, U.S. Deputy National Security Adviser Anne Neuberger said that pushback from the health care industry was unwarranted due to the serious impact of incidents, citing the recent Change Healthcare ransomware attack.

For hospitals, the most concerning proposal is included in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2025 budget plan, which proposes to dock payments to hospitals from the 2029 fiscal year onward if they aren’t meeting “essential” cybersecurity goals (see p. 82 of this pdf).

In response to the budget plan, the American Hospital Association (AHA) issued a statement in mid-April saying that cutting payments would be counterproductive and that this was a type of victim blaming, “as if they were at fault for the success of hackers in perpetrating a crime.”

Seriously Risky Business did not find the association’s statement all that persuasive, so we spoke to a chief information security officer (CISO) in the U.S. health care industry for a deeper understanding.

He said that although at one level using the government’s purchasing power to drive change makes sense, the average operating margin of U.S. hospitals is only 2 percent and that many hospitals operate at a loss, particularly small ones in rural or dense urban areas. (This data published in March says U.S. hospital operating margins in 2022 were -3.8 percent.)

Additionally, the CISO told us the proposal did not recognize the different circumstances of small, medium, and large hospitals and treated them all identically. He cited a small 50-bed hospital in which he does pro bono work that has just two information technology (IT) personnel who are responsible for all of the hospital’s IT and security, as well as dealing with many of its biomedical devices.

The two hospitals in that area have not had a positive operating margin since the 1970s and essentially operated through government grants and the efforts of the local community.

And ironically, although their cybersecurity capacity is extremely limited, their risk exposure is also limited because systems are not typically networked and connected.

“It’s going to be an inconvenience, no doubt,” he said.

“But they’re going to fire up some laptops, get on their guest Wi-Fi, log back into their [web-based] EMR [electronic medical record] and they’re going to keep going.”

The CISO pointed to the 405(d) Program, a joint health care industry and government effort to align industry security practices. It provides tailored advice for small, medium, and large organizations.

That kind of tailored approach seems appropriate. Perhaps a means-tested carrot-and-stick approach will work to encourage larger hospital systems to improve. And although larger organizations are more capable, more is at risk because devices are more often networked and integrated.

Beyond looking just at hospitals, Neuberger is correct and there are organizations generating large profits that can afford to ramp up their cybersecurity standards. UnitedHealth Group, for example, the parent company of Change Healthcare, earned $28.4 billion from revenues of $324 billion.

We are not averse to governments using the regulatory stick, but it should be used to motivate the strong rather than punish the weak.

Three Reasons to Be Cheerful This Week:

- How to mitigate civil society cyber threats: Nine government agencies have co-authored a guide on “how to mitigate cyber threats,” aimed at civil society with limited resources. This is great, and these types of organizations really do need help. But it would be even better if there were a plain English or “For Dummies” version as the guide is still written for an information security-savvy audience.

- U.K.-wide malware filtering: The U.K.’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) announced a new “Share and Defend” capability to block access to malicious websites at the internet service provider (ISP) level. The NCSC will create blocklists with data from partners such as threat intelligence firms and will push these out to ISPs. The 2023-2030 Australian Cyber Security Strategy contains similar plans; and Telstra, the country’s largest telecommunications company, already filters malicious traffic for customers.

- Firefox privacy protection from bounce tracking: Mozilla is working on a new anti-tracking feature called Bounce Tracking Protection for its Firefox web browser. Bounce tracking, aka redirect tracking, is a technique to track visitors that is increasingly being used as browsers remove third-party cookies. A bounce-tracked link sends a browser to an intermediary website that can set a first-party cookie before immediately transferring the user to the genuine site.

Shorts

LockBit Accused’s Cybercrime Resume

Krebs on Security has an excellent article piecing together the digital breadcrumbs left by Dmitry Yuryevich Khoroshev, the Russian national accused by a multinational law enforcement effort of being leader of the LockBit ransomware group. The history Krebs assembles doesn’t prove that Khoroshev is behind “LockBitSupp,” the online persona of LockBit’s leader. However, Khoroshev’s skills and “work history” mean it is very plausible.

FTC Puts Car Manufacturers on Notice

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has spelled out areas of automobile data collection that it views as potential concerns. The FTC refers to recent enforcement actions that have covered geolocation data, surreptitious disclosure of sensitive information and using consumer data for automated decision-making. Its take home message is “the easiest way that companies can avoid harming consumers from the collection, use, and sharing of sensitive information is by simply not collecting it in the first place.”

Scattered Spider Still Around

Security firm Resilience says the group known as Scattered Spider is still operating and it has observed it targeting over 30 companies. Scattered Spider, aka Octo Tempest and one of the Lapsus$-like groups, is infamous for its disruptive attacks on MGM and Caesars casinos. These groups use a novel set of very successful techniques that are often able to break through organization’s standard cybersecurity practices. These aren’t stable groups with fixed membership but, rather, a set of individuals who work together on particular capers, so we don’t know what it really means to say that “Scattered Spider is still operating.” Reuters reports that the FBI is getting closer to charging hackers involved in these crimes.

Risky Biz Talks

In the latest “Between Two Nerds” discussion, Tom Uren and The Grugq look at how different types of secrecy-obsessed organizations learn.

From Risky Biz News:

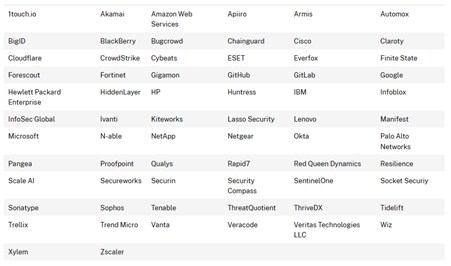

Sixty-eight tech companies pledge to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s (CISA’s) Secure by Design project: Sixty-eight of the world’s largest tech companies have signed a voluntary pledge to design and release products with better built-in security features. The pledge is part of CISA’s Secure by Design (SbD) initiative, a project the agency started in 2023 to promote better cybersecurity baselines and practices.

Signatories include the likes of Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Cloudflare, and Netgear. The full list is in the table below.

[more on Risky Business News, including a high-level summary of recommendations]

Black Basta social engineering: The Black Basta ransomware gang is using a new social engineering tactic as a way to gain a foothold inside corporate networks. According to security firm Rapid7, Black Basta operators are flooding the email inboxes of employees of a targeted company. The group calls affected employees posing as their IT help desk and offering assistance. The campaign has been taking place since last month, and its end goal has been to install remote access software on the targeted networks. Rapid7 says Black Basta uses the software to collect credentials and move laterally inside a victim’s network.

In all observed cases, the spam was significant enough to overwhelm the email protection solutions in place and arrived in the user’s inbox. Rapid7 determined many of the emails themselves were not malicious, but rather consisted of newsletter sign-up confirmation emails from numerous legitimate organizations across the world.

Ebury botnet: Security firm ESET says that 15 years after it launched, the Ebury botnet is still operating and installed on more than 100,000 Linux and *NIX servers. The botnet is currently being used to spread spam, perform web traffic redirections, and steal credentials. It was recently modified to also plant web skimmer malware to steal payment card details, and perform AitM attacks to steal SSH credentials and crypto-wallet keys. ESET says Ebury operators are also selling access to infected hosts as part of initial access schemes. Recent Ebury attacks involved the use of zero-days in administrator software to compromise servers in bulk. Some Ebury campaigns gained full access to large ISPs and well-known hosting providers. The group also hacked the server infrastructure and stole data from other cybercrime crews.

.png?sfvrsn=4156d4f8_5)

-(1)-(1).png?sfvrsn=1bc11cd_4)