The Anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine

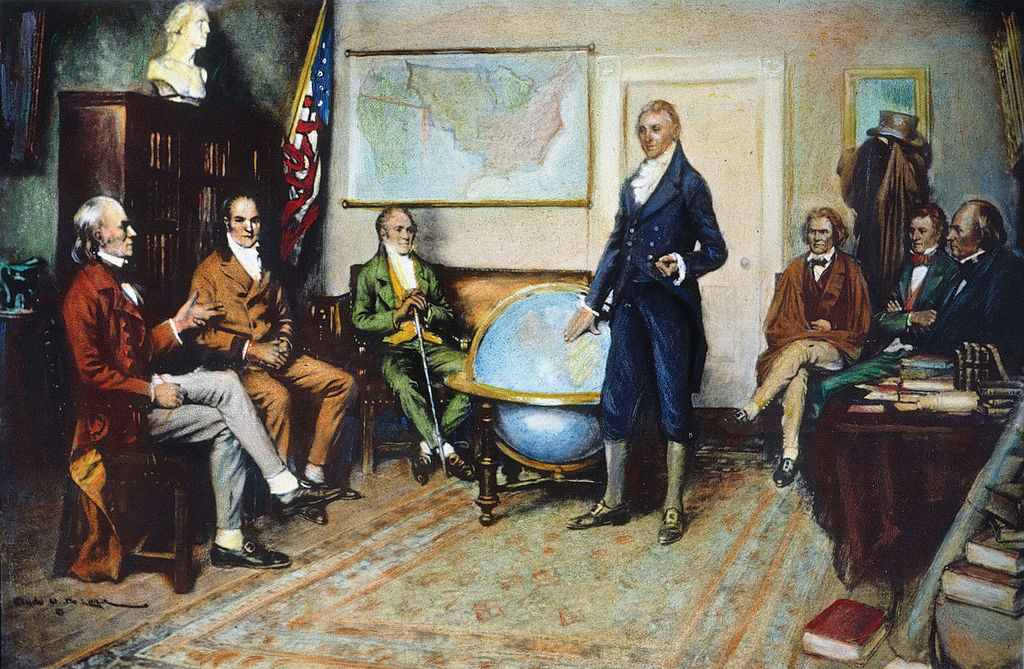

Today is the 195th birthday of the Monroe Doctrine. On December 2, 1823, President James Monroe proclaimed in his Seventh Annual Message to Congress that the United States would oppose any European efforts to colonize or reassert control in the Western Hemisphere:

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Today is the 195th birthday of the Monroe Doctrine. On December 2, 1823, President James Monroe proclaimed in his Seventh Annual Message to Congress that the United States would oppose any European efforts to colonize or reassert control in the Western Hemisphere:

[T]he American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers . . . . We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere. But with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintained it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.

Monroe’s proclamation is a momentous example of the president’s vast constitutional power to set and communicate U.S. foreign policy. This was not just any kind of diplomatic policy, however.

This was drawing a red line—with an implicit war threat—even though the United States at the time lacked the military power to back it up. The United States was counting on Britain, which too wanted to keep continental European powers out of Latin America, to also intervene if necessary. “In its sweep and bravado,” writes Kori Schake in “Safe Passage: The Transition from British to American Hegemony,” “the Monroe Doctrine has few equals, especially since it was promulgated by a country that was not the peer of the states—Britain, France, and Spain—whose activity it sought to curtail.” The real strategic brains behind this move was then-Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, and for more on his role I highly recommend Charles Edel’s book, “Nation Builder: John Quincy Adams and the Grand Strategy of the Republic.”

The late legal historian David Currie noted in his volumes on the Constitution in Congress that “[v]irtually no one questioned [Monroe’s proclamation] at the time. Yet it posed a constitutional difficulty of the first importance.” The president was unilaterally committing the nation to war if European states crossed Monroe’s red lines, but it was Congress’s sole prerogative to initiate war. By putting U.S. prestige and credibility on the line, his threat limited Congress’s practical freedom of action if European powers chose to intervene. When he succeeded Monroe as president, Adams faced complaints from opposition members of Congress that Monroe’s proclamation had exceeded his constitutional authority and had usurped Congress’s power by committing the United States—even in a nonbinding way—to resisting European meddling in the hemisphere.

As I argued in this article, since that time, the president’s power to threaten war has grown dramatically and become central to American foreign policy. These days the president can threaten nuclear strikes by tweet. Curiously, to the extent there was ever any real question whether there are constitutional limits on the president’s power to threaten war, it has vanished almost completely from legal discussion, and that evaporation occurred even before the dramatic post-World War II expansion in presidential power to make war. That, however, leaves a big disconnect between constitutional debates and strategic ones: lawyers argue endlessly about the president’s authority to use force, while constitutionally unconstrained threats—to coerce or deter enemies and to reassure allies— remain one of the most important ways in which the United States government actually wields its military might, and have enormous consequences for sustaining peace or provoking war.

.png?sfvrsn=4156d4f8_5)