On Appeal, House Republicans Press Forward With Legal Challenge to Proxy Voting

House Republicans urged the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit to reverse the district court’s dismissal of their legal challenge to the House’s proxy voting system during oral argument on Nov. 2.

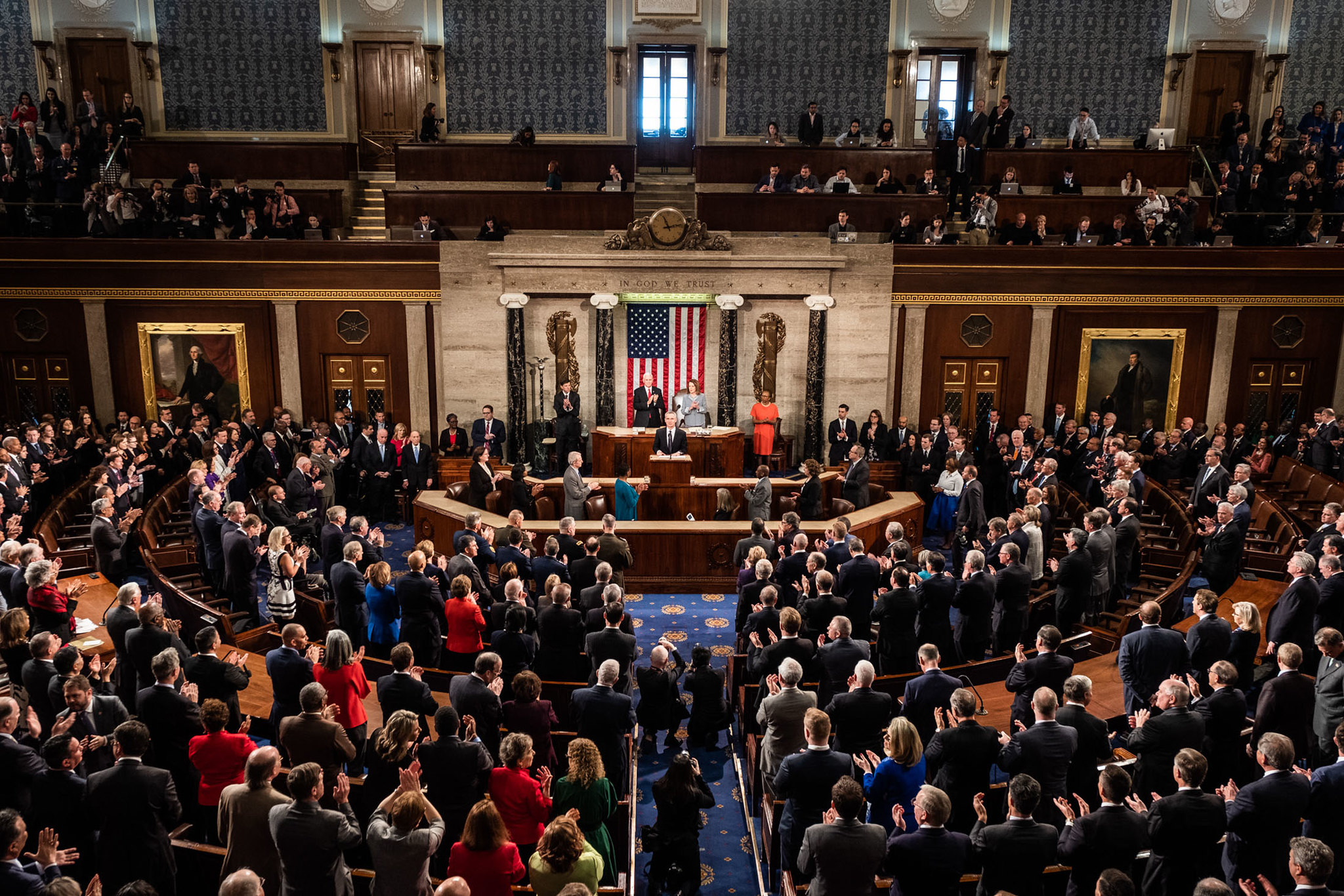

When the U.S. House of Representatives adopted a proxy voting system in May to allow members to vote remotely during the coronavirus pandemic, Republican lawmakers had a lot to say about it. House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy called the system an “unconstitutional power grab.” Rep. Liz Cheney described it as an “abuse of power.” And Rep. Jim Jordan said it was “scary stuff.”

While the House’s embrace of proxy voting was neither especially sinister nor the product of a Democratic power play, the system has been the subject of a months-long legal challenge brought by House Republicans and several of their constituents. In late May, the coalition sued House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Clerk of the House Cheryl Johnson and House Sergeant at Arms Paul Irving in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in an effort to enjoin the use of proxy voting. After losing on jurisdictional grounds, Republicans sought to salvage their case, known as McCarthy v. Pelosi, on appeal.

During a fast-paced telephonic argument before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit on Nov. 2, the plaintiffs urged a three-judge panel to allow their challenge to move forward. But the defendants fought spiritedly to prevent that from happening. Over the course of roughly 70 minutes, Judges Sri Srinivasan, Judith Rogers and Justin Walker peppered Charles Cooper, the counsel for House Republicans, and Douglas Letter, the general counsel of the House of Representatives, with questions. Cooper faced the lion’s share of the panel’s inquiries. The veteran attorney confronted the unenviable task of convincing the circuit not only to reverse the district court’s dismissal of the case but also to engage with the merits of the plaintiffs’ lawsuit and hold that proxy voting is invalid.

Although Rogers and Walker entertained a brief discussion on the merits, the court focused overwhelmingly on the issues of whether the case is justiciable and whether the plaintiffs have standing to sue. The panel’s assiduous attention to those topics suggests that they, like the district judge, will decline to rule on the constitutional questions raised in the lawsuit.

The House adopted the proxy voting system at issue in McCarthy on May 15, almost two months after a number of lawmakers fled Capitol Hill to avoid gathering en masse and to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus. The proxy system, enacted via H. Res. 965, established a mechanism that allows an absent House member to designate another member to cast votes on his or her behalf during the pandemic. Under the authorizing resolution, a representative designates his or her proxy in a letter submitted to the clerk of the House. Proxies must vote or record the presence of the members whom they represent pursuant to the specific instructions those members gave them. And any individual who votes by proxy counts toward the majority the House needs for a quorum.

On May 26, House Republicans initiated their legal challenge to proxy voting. They sought to enjoin the system’s use on the grounds that it violates the Constitution’s quorum requirement, the “yeas and nays” requirement, the nondelegation doctrine and the “structure” of the founding document. At the heart of their case is the assertion that the Constitution requires members of Congress to be physically present for the House to conduct official business such as votes. Because proxy voting allows members to vote and be counted as “present” when they are not physically gathered in the Capitol, the plaintiffs argue, the system is unconstitutional. At oral argument, Rogers referred to this assertion as the idea that members must have “boots on the ground” or “feet on the soil” for their votes to be considered validly cast.

House Republicans name three defendants in their lawsuit: Speaker Pelosi, Clerk of the House Johnson and House Sergeant at Arms Irving. Under House rules, Johnson is responsible for conducting record votes and quorum calls. And under H. Res. 965, Irving is tasked with determining whether a “public health emergency” due to the coronavirus “is in effect.” Once he determines it is, Pelosi may commence the renewable 45-day “covered period” during which members can vote by proxy. Pelosi first initiated this period on May 20 and has extended it several times since. She did so most recently on Nov. 13, allowing members to continue voting by proxy through Dec. 31.

Although the plaintiffs urged the district court to permanently enjoin proxy voting because the practice allegedly violates the spirit and letter of the Constitution, Judge Rudolph Contreras never decided that issue. Rather, in a thorough opinion issued on Aug. 6, Contreras dismissed the plaintiffs’ case on the ground that the Constitution’s Speech or Debate Clause renders Pelosi, Johnson and Irving immune from civil suit for their administration of the proxy system.

The case law on the issue is clear, Contreras opined. Both the U.S. Supreme Court and the D.C. Circuit have held that the Speech or Debate Clause gives members of Congress and congressional aides and officers absolute immunity from civil suit for their performance of all “legislative acts.” In Gravel v. United States, the Supreme Court explained that an act is “legislative” if it is “an integral part of the deliberative and communicative processes by which Members participate in committee and House proceedings with respect to the consideration and passage or rejection of proposed legislation or with respect to other matters which the Constitution places within the jurisdiction of either House.” Subsequently, in Consumers Union v. Periodical Correspondents’ Association, the D.C. Circuit held that the enforcement of congressional rules by congressional officers (such as the sergeant at arms) falls “within ‘the sphere of legislative activity’” protected by the Speech or Debate Clause.

In his opinion, Contreras identified Consumers Union as the precedent “control[ling]” how he ruled in the proxy voting case. The judge also stated that he could “conceive of few other actions, besides actually debating, speaking, or voting, that could more accurately be described as ‘legislative’ than the regulation of how votes may be cast.” That regulation of voting—an essential element of the legislative process—lies at the core of Pelosi, Johnson and Irving’s administration of the proxy system, Contreras concluded.

On appeal, the plaintiffs aim to overturn the district court’s holding. They also urge the D.C. Circuit to find that they have standing to bring their case and ask the circuit to direct Contreras to enter a permanent injunction against the proxy system.

In their opening appellate brief, the plaintiffs attempt to overcome the problem posed by the Speech or Debate Clause by highlighting the distinction between legislative acts, which the clause protects, and actions performed in the course of implementing or executing those acts, which the clause does not protect. The Supreme Court has recognized this distinction in a series of cases that the plaintiffs cite: Kilbourn v. Thompson, Dombrowski v. Eastland and Powell v. McCormack. In Dombrowski, for instance, the court held that the Speech or Debate Clause did not shield the chief counsel of a Senate subcommittee from a lawsuit alleging that the attorney had violated the rights of private parties while seizing records the subcommittee had subpoenaed. Although the senators who issued the subpoena were immune from suit under the Speech or Debate Clause, the counsel who enforced their directive was not.

Similarly here, the plaintiffs argue, the Speech or Debate Clause immunizes the representatives who enacted H. Res. 965 but not the individuals now implementing it. Under this theory, Pelosi, Johnson and Irving cannot be considered immune from suit.

When Cooper raised this distinction at oral argument, Srinivasan interjected almost immediately. McCarthy seems different, the chief judge stated, and the distinction between legislative acts and actions executing them cannot be applied cleanly here. This case, Srinivasan continued, concerns a challenge to the implementation of a House rule, but the very implementation of that rule is intertwined with the business of legislating because that rule concerns how members vote. The conduct challenged in McCarthy thus seems integral to the legislative process, the judge said.

Cooper strongly objected to that conclusion. In response to the chief judge’s comments and at several other points during the argument, Cooper contended that proxy voting cannot be integral to the legislative process since that process has existed without a proxy option for more than 230 years. Although Rogers did not address that assertion directly, she took issue with an analogous argument Cooper raised later—that because Congress has never before embraced proxy voting suggests that the proxy system the House has adopted is unconstitutional. Prior congressional history “doesn’t necessarily decide the question,” Rogers stated. Similarly, one could argue that because proxy voting was not integral to the legislative process in the past does not mean it is not essential now.

Pressing on, the plaintiffs revisited a point they made before the district court—that the breadth of the immunity conferred by the Speech or Debate Clause has disquieting implications. “If the Speech or Debate Clause applies whenever a legislative directive relates to voting,” they write on appeal, “it necessarily follows that the Clause would bar any suit by Members challenging the constitutionality of any House rule concerning voting.” This absolute jurisdictional bar would block challenges even to rabidly discriminatory rules, such as rules “forbidding women or Black Members from voting,” the plaintiffs write.

Letter conceded that the immunity conferred by the Speech or Debate Clause is indeed absolute. But he also offered several responses to the plaintiffs’ hypotheticals. As an initial matter, Letter reiterated that the rule at issue in McCarthy is not discriminatory; H. Res. 965 permits any member to vote by proxy. And the defendants added in their response brief on appeal that even if the House passed a rule blocking members of a particular racial background or gender identity from voting, “the [Speech or Debate] immunity analysis might be different” for those rules, which “completely exclude Members from the legislative process in violation of their individual rights.” At oral argument, Srinivasan seemed to agree with this point. The chief judge quoted the Supreme Court’s decision in Gravel v. United States, which affirmed the “judicial power to determine the validity of legislative actions impinging on individual rights.”

During an exchange with Walker, Letter also suggested that an alternative remedy could “very likely” provide relief where the Speech or Debate Clause bars a lawsuit challenging a discriminatory House rule. If, for instance, the House enacts a law while an internal rule barring female members from voting is in effect, an individual injured by that law could file a lawsuit alleging that the law in question was unconstitutionally passed. But the plaintiff would be suing the federal government, which would be enforcing the law, Letter said. The individual could not sue the members of Congress who voted to adopt the discriminatory rule or the congressional officers who enforced it, as the Speech or Debate Clause cloaks them in immunity.

The judges turned their attention next to the issue of standing, or whether the House’s implementation of proxy voting injured House Republicans, thus allowing them to challenge the system in court. The plaintiffs have argued that proxy voting injures them by diluting their voting power. In their filings before the district court, they offered a hypothetical to illustrate that argument. Assuming proxy voting is constitutionally invalid, the plaintiffs say that if 200 members vote on a bill in person and 50 vote by proxy, the strength of the physically present member’s vote would decrease from 1/200 to 1/250. To the plaintiffs, this constitutes a clear mathematical dilution of their voting power and an injury worthy of judicial redress.

Contreras cautiously disagreed. Although the judge did not rule on the issue, he observed that in prior D.C. Circuit cases—Vander Jagt v. O’Neill, Michel v. Anderson and Skaggs v. Carle—the court has accepted theories of vote dilution when those theories have “define[d] Member voting power relative to the entire congressional body.” In Michel, for instance, the circuit held that representatives had standing to challenge a House rule that permitted delegates from the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands to vote in the Committee of the Whole—a procedural innovation that allows the entire House to operate as a committee on which every member sits. The rule at issue in Michel expanded the number of seats on the committee from 435 to 440, thereby diluting the strength of a member’s vote from 1/435 to 1/440.

In the proxy voting case, Contreras observed, the math is quite different. The plaintiffs here contend that voting power should be measured not against the total number of elected representatives, but against the number physically gathered in the Capitol. “The parties do not cite, and the Court has not found, any cases adopting Plaintiffs’ theory,” Contreras concluded.

At oral argument, Srinivasan seemed to question whether vote dilution was truly the injury the plaintiffs sustained. The chief judge stated that he understood the potential injury in the case to stem from a situation in which proxy voting delivers a legislative defeat to the plaintiffs that they would not otherwise have suffered if the proxy system were not in place. In other words, injury arises when proxy voting is the “but for” cause of a particular bill passing or not passing. As Srinivasan put it, the theory is essentially that “we would have won, except that somebody else got to vote who shouldn’t have gotten to vote.”

Cooper replied that this was not the plaintiffs’ theory. Indeed, he emphasized that the only injury alleged is the injury the circuit has previously recognized in Vander Jagt, Michel and Skaggs—that of vote dilution.

Srinivasan continued to probe the parties’ theories of standing. In an exchange with Letter, the chief judge stated that the defendants’ theory seems to be that as long as a representative’s vote counts as 1/435, there is no standing to sue. But as soon as that denominator changes, as it did in Michel when a House rule added five seats to the Committee of the Whole, a representative would have standing. Letter said that this understanding of the defendants’ theory is correct if Michel is the controlling case.

But in their response brief on appeal, the defendants argue that a different case, Raines v. Byrd, should govern the court’s analysis of whether House Republicans have standing to sue. In Raines, the Supreme Court considered whether four senators and two representatives had standing to challenge the constitutionality of the Line Item Veto Act, a statute that gave the president the power to cancel particular spending and tax benefit measures after signing them into law. The members of Congress who brought the lawsuit argued that the act injured them by diluting, as the court put it, their “institutional legislative power.” But the Supreme Court rejected this “abstract” theory of injury. The court held that because the lawmakers in question had “not been singled out for specially unfavorable treatment as opposed to other Members of their respective bodies,” their claimed “diminution of legislative power” could not satisfy the essential elements of injury—that it be “personal, particularized, concrete, and otherwise judicially cognizable.” The lawmakers’ alleged injury therefore did not give rise to standing.

In the current case, the defendants assert categorically that “Raines governs cases about ‘the standing of individual Members of Congress.’” They add that because any member can vote by proxy, House Republicans have not been singled out for the specially unfavorable treatment required for standing. Thus, Raines bars the plaintiffs’ suit.

Contreras disagreed with that argument in his opinion for the district court. While the judge did not definitively resolve the issue, he wrote that Raines likely would not apply to the proxy voting case because Raines involved an interbranch dispute between members of Congress and executive branch officials, whereas the proxy voting case involves an intrabranch dispute among lawmakers. Contreras therefore concluded that D.C. Circuit cases concerning standing in intrabranch disputes—such as Vander Jagt, Michel and Skaggs—should guide the court’s standing analysis.

In the 10-page section of their brief devoted to Raines, however, the defendants never explicitly grapple with the inter- versus intrabranch distinction Contreras made. The closest they come to doing so is when they assert that Raines should “apply equally to suits by legislators alleging injuries to themselves in their capacity as Members, as to suits by legislators alleging injuries to Congress.”

Although Letter and the judges on the panel made several passing references to Raines during oral argument, the case received little attention. Indeed, the only comment specifically related to the substance of Raines was Letter’s statement that unless Congress adopts a rule that individually discriminates against particular members, courts should not review the rules Congress sets regarding voting.

This, the defendants argue, is the fundamental principle at issue in the proxy voting case: that federal courts should, as a general matter, avoid interfering in Congress’s internal affairs. The defendants point to the circuit’s recent en banc decision in Committee on the Judiciary of the House of Representatives v. McGahn to further support that proposition. In that case, the circuit noted the “separation of powers concern[s]” raised “in the context of individual legislator suits,” such as the proxy voting case here.

Walker zeroed in on those concerns in a heated exchange with Cooper. During that discussion, the judge expressed outright hostility to the idea that House Republicans’ challenge to proxy voting is justiciable. Walker’s assessment was blunt: “It seems to me that this is yet another case where one group of politicians [is] sparring with another group of politicians and they want a federal court to pick a side.” Whether the panel views this lawsuit “under standing jurisprudence, political-question jurisprudence, Speech [or] Debate jurisprudence—the principle behind those doctrines is that this Court, no court, is supposed to be an instrument of partisan warfare,” Walker exclaimed. “Tell me why I shouldn’t view this case as a group of Republican representatives trying to get their way in Congress against a group of Democratic representatives.”

In an earlier exchange, Rogers raised concerns about a different principle: congressional discretion to tweak its rules to meet the moment. She feared that the plaintiffs’ insistence on the constitutional necessity of casting votes in person would force the House and the Senate to “shut down” if a pandemic even more severe than the one caused by the coronavirus precluded members from convening in the Capitol or in any other physical location.

After resisting the hypothetical for several minutes, Cooper stated that he “believe[d] the Constitution would have to be amended” to permit members to conduct official business virtually. Walker immediately noted that this would force the House and the Senate to convene in person with enough lawmakers to pass an amendment with the requisite supermajority—an outcome rendered impossible by the hypothetically dire epidemiologic circumstances. “That may be a very good reason,” Cooper said, choosing his words with slow and excruciating care, “for Congress and the country to consider such an amendment in a time when it can take place”—when American lawmakers can gather in person.

If the plaintiffs are correct, in other words, Congress would have to take up constitutional reform far in advance of the spread of an even more lethal virus to ensure that such a crisis does not bring the body’s work to a screeching and temporarily irremediable halt.

While Rogers’s hypothetical brought into view the potentially severe consequences of ruling for the plaintiffs on the merits of their challenge, it seems unlikely that Rogers and her colleagues will engage with the physical-presence issue when they decide the proxy voting case. Instead, the oral argument suggests that the court’s ruling may be narrower, examining whether Contreras got it right on the Speech or Debate Clause and perhaps touching on the implications of the clause’s sweeping immunity or the issue of standing. But don’t hold your breath for much more.

The court’s decision could, nevertheless, be significant. Any ruling on the Speech or Debate Clause will inform how deferential courts will be going forward to Congress’s exercise of its constitutionally committed authority to determine the rules of its own proceedings. The decision may also affect the frequency with which members of Congress pursue challenges like McCarthy in the future—either emboldening or discouraging obstinate American lawmakers from seeking federal courts’ intercession in disputes perhaps best resolved in Congress.

Although Contreras noted during a hearing before the district court that he expected the proxy voting case to continue on appeal, the circuit panel made no similar remarks about its expectations for the future of McCarthy. Whether the parties decide to petition for en banc review, appeal to the Supreme Court or simply accept the outcome they receive will depend on the exact contours of Srinivasan, Rogers and Walker’s forthcoming ruling. The public should expect to learn more soon.

.jpeg?sfvrsn=e13b9854_7)