On Bad Lawyering in Presidential Scandals Past and Present

Almost two decades ago, a few short months after being hired as an editorial writer by the Washington Post to write high-minded legal-affairs editorials on those important questions that arise in the life of our nation, one of the present writers found himself confronted by Monica Lewinsky—and her outrageous first lawyer, William Ginsburg:

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Almost two decades ago, a few short months after being hired as an editorial writer by the Washington Post to write high-minded legal-affairs editorials on those important questions that arise in the life of our nation, one of the present writers found himself confronted by Monica Lewinsky—and her outrageous first lawyer, William Ginsburg:

"I kissed that girl's inner thighs when she was six days old—I said, ‘Look at those little polkas,' " says lawyer William Ginsburg of his client, Monica Lewinsky, in the March 2 issue of Time magazine. In the same article, this most grandiloquent of attorneys complains that "the only jobs [Lewinsky's] been offered [recently] are talk-radio crap and posing nude," and he frets that "she's also worried about dating." After all, "Who's going to go out with her?"

Ginsburg's concern about his client's job prospects and dating life are merely the latest and most extreme instances of the penchant he has displayed—since catapulting himself to national prominence—for saying almost anything about Lewinsky. It is a penchant that would be merely an amusing sideshow to the presidential scandal were Lewinsky's legal strategy—and hence her lawyer's role—not so central to the investigation of President Clinton.

The comments began at the outset of the scandal, when Ginsburg used violent metaphors to describe Lewinsky's relationship with both the president and Starr. If "the Office of Independent Counsel has no substantial evidence or reason to go after Monica Lewinsky, they're ravaging her," he told ABC's "Nightline." "If it's true she had some sort of relationship with the president, then she's being ravaged."

Ginsburg had, in his outrageous way, a profound effect on the life of this country. His antics at the outset of the Lewinsky investigation helped ensure that Lewinsky did not secure a quick immunity deal with Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr. This led to a lengthy, months-long, standoff between the White House and the Independent Counsel that gave the Clinton forces time to regroup and counterattack in a fashion that proved devastating for Starr and arguably saved the Clinton presidency.

Ginsburg’s clownish service to Clinton’s presidency, however, came entirely at the expense of the interests of his actual client, who was left in jeopardy and exposed to public ridicule for months before competent counsel eventually secured her a deal similar to the one offered her on day one.

Really bad lawyering in high-profile national scandals can matter a lot.

Fast forward to this week.

If you’re a bomb-throwing president whose inability to control your own outbursts has gotten you in trouble, who has trouble telling the truth, who has a more general impulse control problem, and who is not wise to the ways of Washington, you’d probably want in a lawyer a careful, Washington-savvy operator with great credibility in the bar, in the press, and on Capitol Hill. You’d want someone whose word carries weight. You’d certainly want someone who would never make your problems worse by, say, throwing bombs of his own or issuing statements that turned out not to accurately reflect the public record. You wouldn’t choose a lawyer who would compound your errors and lies with errors and lies of his own.

You wouldn’t want, in other words, a lawyer who—as Ginsburg did for Lewinsky—made a bad situation worse.

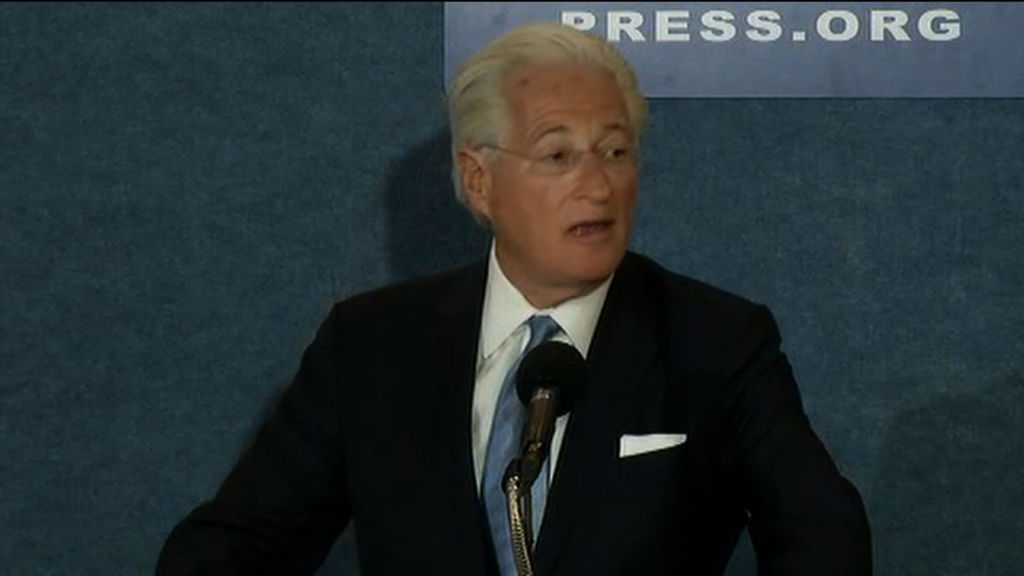

Unless, that is, you were President Donald Trump, whose choice of outside counsel—Marc Kasowitz—is looking increasingly Ginsburgian in his public utterances. There are differences, of course. Kasowitz isn’t clownish, as Ginsburg was. He isn’t making bizarre remarks—for example, about kissing his client’s inner thighs. And he is doing some things that Ginsburg did not do: for example, issuing public statements on key factual matters that are apparently untrue. The differences aside, however, Kasowitz has, in his few short weeks on the job, let’s just say, not been of service to a client who desperately needs legal help managing his own disasters, not a lawyer who is generating new ones for him.

Unlike many of the lawyers who have reportedly declined to represent Trump, including Ted Olson, Paul Clement, and Mark Filip, Kasowitz has no experience in executive branch lawyering. Rather, he is a New York corporate attorney with a long history representing Trump in a variety of matters, ranging from real estate to an ultimately failed libel suit filed against a Trump biographer. His firm’s website describes him as “the toughest of the tough guys.” He also reportedly represents a bunch of clients with, you guessed it, ties to the Kremlin.

Kasowitz, like Ginsburg, comes from a different legal culture than the one he has now entered. Ginsburg was a medical malpractice attorney from California. Kasowitz comes from the rough and tumble world of New York real estate litigation. In that world, Kasowitz is a kind of a implementer of Trump’s broad strategy of using the law and the threat of litigation—whether merited or not—as a cudgel in business, a means of intimidating those in your way. The Washington legal culture of scandal management works differently. It is not sensitive to price; unlike a business competitor, you can’t outspend the federal government when it is committed to pursuing a high-stakes investigation. It is sensitive to public opinion. And reputational damage to the client matters a great deal more when the client has congressional and voter relations to maintain than when the only thing that matters is who wins, who pays, and how much.

This is clearly causing problems. The New York Times has just released a story detailing Kasowitz’s rocky first few weeks advising Trump:

His visits to the White House have raised questions about the blurry line between public and private interests for a president facing legal issues. Mr. Kasowitz in recent days has advised White House aides to discuss the inquiry into Russia’s interference in last year’s election as little as possible, two people involved said. He told aides gathered in one meeting who had asked whether it was time to hire private lawyers that it was not yet necessary, according to another person with direct knowledge.

Such conversations between a private lawyer for the president and the government employees who work for his client are highly unusual, according to veterans of previous White Houses. Mr. Kasowitz bypassed the White House Counsel’s Office in having these discussions, according to one person familiar with the talks, who like others requested anonymity to discuss internal matters. And concerns about Mr. Kasowitz’s role led at least two prominent Washington lawyers to turn down offers to join the White House staff.

…Since asserting influence in the White House in recent weeks, Mr. Kasowitz has discussed establishing an office on White House grounds in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, where much of the president’s staff works, according to multiple people familiar with the deliberations. Such an arrangement would have Mr. Kasowitz and his team frequently crossing paths with potential witnesses.

…Partly because of concerns that Mr. Kasowitz is undermining the White House Counsel’s Office, at least two veteran Washington lawyers — Emmet Flood, a partner at Williams & Connolly, and William A. Burck, a partner at Quinn Emanuel — rejected offers to join the counsel’s office to help represent the administration in the Russia inquiry, according to people familiar with the hiring discussions, although they may yet represent individual White House officials.

Other noted criminal defense lawyers have similarly rejected offers to join Mr. Trump’s private legal team because of a range of uncertainties, including how much control Mr. Kasowitz exercises over his client, whether their advice would be secondary to his and whether Mr. Trump would pay legal bills. Besides Mr. Kasowitz, Mr. Trump’s personal legal team includes his partner, Michael J. Bowe, and Jay Sekulow, a Washington lawyer who specializes in free speech and religious liberties.

Kasowitz’s lack of experience with this sort of investigation has been very much on display in Trump’s response to Comey’s testimony. So far, Kasowitz has made two public statements on the testimony of former FBI Director James Comey—one released the day of Comey’s testimony, and which Kasowitz also read essentially word-for-word at a press conference in New York, and one released the following day.

The first thing that jumps out about Kasowitz’s statements is how uncareful they are. The statements contain notable spelling, grammatical, and formatting errors. None of these is an egregious sin, but they are also not the work product of a high-class firm representing the President of the United States in a high-stakes legal matter. And they turn out to be telling.

Because literacy aside, the substance of both statements is, well, Ginsburgian in its incompetence. This is significant because the Clinton lawyers and public messaging professionals ultimately defeated the Starr investigation by winning a sustained messaging war—something Ginsburg helped give them time to do. Kasowitz, if his initial performance is any guide, does not seem up to the battle.

The first statement boldly contradicts Comey’s sworn testimony; it declares that Trump “never, in form or substance, directed or suggested that Mr. Comey stop investigating anyone, including suggesting that that Mr. Comey ‘let Flynn go.’” It also insists that, “The President also never told Mr. Comey, ‘I need loyalty, I expect loyalty’ in form or substance.” Fair enough. This is going to be a he-said-he-said situation.

But the statement also takes issue with Comey’s description of his decision to disclose to the New York Times, through a friend, the contents of an unclassified memo documenting Trump’s suggestion that he drop the Flynn investigation. And it does so in a fashion that Kasowitz simply cannot support.

To review, in an exchange with Senator Susan Collins, Comey stated:

COLLINS: And finally, did you show copies of your memos to anyone outside of the Department of Justice?

COMEY: Yes.

COLLINS: And to whom did you show copies?

COMEY: I asked—the president tweeted on Friday, after I got fired, that I better hope there’s not tapes. I woke up in the middle of the night on Monday night, because it didn’t dawn on me originally that there might be corroboration for our conversation. There might be a tape. And my judgment was, I needed to get that out into the public square. And so I asked a friend of mine to share the content of the memo with a reporter. Didn’t do it myself, for a variety of reasons. But I asked him to, because I thought that might prompt the appointment of a special counsel. And so I asked a close friend of mine to do it.

Comey was dismissed on Tuesday, May 9. On May 12—which was, as Comey said, a Friday—the President sent his now-famous tweet threatening that he had “tapes” of his conversations with Comey. The New York Times story on Comey’s practice of taking notes on his conversations with Trump, which reported the existence of a memo documenting the Flynn exchange, was published the following Tuesday, May 16. From Comey’s testimony here, the timeline seems clear: Comey “woke up in the middle of the night” on Monday, May 15 and asked a friend, who has now been identified as Columbia Law Professor Dan Richman, to disclose the contents of the memo to the Times, which published the story—by Michael Schmidt—the next day. The following day, May 17, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein appointed Robert Mueller as special counsel.

Yet in his statement, Kasowitz declares: “Although Mr. Comey testified he only leaked the memos in response to a tweet, the public record reveals that the New York Times was quoting from these memos the day before the referenced tweet, which belies Mr. Comey’s excuse for this unauthorized disclosure of privileged information and appears to entirely retaliatory” (sic).

The problem is that Kasowitz’s statement appears inconsistent with the public record—not just with Comey’s testimony, but the rest of the public record as well. Julie Davis, a White House reporter for the Times, quickly noted that Kasowitz’s statement did not map to the Times’ reporting:

Kasowitz is mistaken re NYT stories on Comey memos. We never quoted memos prior to Trump's 5/12 tweet re tapes; 1st story doing so was 5/16

— Julie Davis (@juliehdavis) June 8, 2017

Other journalists and news outlets chimed in as well, pointing out the apparent inconsistency.

Kasowitz appears to have felt the need to clarify, because he followed up the next day with a second statement on the same topic:

Numerous press stories have misreported that our statement yesterday incorrectly claimed that the New York Times was reporting details from Mr Comey’s memos the day before President Trump’s May 12, 2017 Tweet because, according to these reports, the first New York Times story to mention the memos specifically was May 16, 2017, which was after the Tweet.

Our statement was accurate and was not referring to the May 16, 2017 story. Rather, Mr. Comey’s written statement, which he testified he prepared from his written memo, describes the details of the January dinner in virtually verbatim language as the New York Times May 11, 2017 story describing the same dinner. That story was the day before President Trump’s Tweet.

It is obvious that whomever was the source for the May 11, 2017 New York Times story got that information from the memos or from someone reading or who had read the memos.

This makes clear, as our statement said, that Mr Comey incorrectly testified that he never leaked the contents of the memo or details of the dinner before President Trump’s May 12, 2017 Tweet (sic).

But this statement, it turns out, only compounds the factual problems with the first one.

The May 11 New York Times story Kasowitz is referring to appears to be Schmidt’s report on the private dinner between Comey and Trump, during which Trump requested the FBI Director’s loyalty. This story does not mention anything about a memo or memos. Kasowitz seems to be arguing that Schmidt’s source for the story must have been a memo written by Comey. If Kasowitz were right, this would mean that Comey had misled the committee under oath and in fact provided Richman or someone else, and through that person the Times, with a memo or memos before Trump tweeted about “tapes”—as opposed to in response to the “tapes” tweet. That would be an explosive allegation.

But Kasowitz does not support it with any facts, and it actually appears to contradict a number of known facts—not just Comey’s testimony but the New York Times’s rather detailed account of its own sourcing and reporting process.

The Times has been admirably clear about the sourcing for both stories. The May 16 story clearly derives from a contemporaneous memo produced by Comey: “Mr. Comey shared the existence of the memo with senior F.B.I. officials and close associates. The New York Times has not viewed a copy of the memo, which is unclassified, but one of Mr. Comey’s associates read parts of it to a Times reporter.”

In contrast, the Times describes the sourcing for the May 11 story as follows: “Mr. Comey described details of his refusal to pledge his loyalty to Mr. Trump to several people close to him on the condition that they not discuss it publicly while he was F.B.I. director. But now that Mr. Comey has been fired, they felt free to discuss it on the condition of anonymity.”

Thanks to the Times’s news podcast, The Daily, we have an even more detailed account of the sourcing for both stories. The podcast’s host, Michael Barbaro, has interviewed Schmidt several times about his reporting on Comey. Here’s how Schmidt described the process of reporting out the May 11 story on the loyalty dinner in a podcast conversation released May 12. (Schmidt’s story begins at around 2:38):

[The morning after Comey was fired] I start making some calls early. Folks who knew Comey are up and they’re all spun up obviously about what happened, saying, we’re just trying to figure out what happened here. Why did this happen, do they know why this happened? And they say, this guy said, “Well there’s this dinner.”

I said, “What do you mean, there’s this dinner.”

“There’s this dinner that Comey had at the White House with Trump.”

And I say, “Well, what?”

“Well, I don’t know everything about it,” and he starts getting a little squirrely. So I say, “You gotta tell me more, you gotta tell me more.”

Basically throughout the rest of the day what I figure out is that seven days after Trump was sworn in, Comey gets summoned to the White House by Trump for dinner, one on one dinner… And if you talk to folks who talked to Comey about this, they say, “You want to know why Comey got fired? Comey didn’t want to pledge allegiance to Trump.”

Compare that to Schmidt’s description of how he came to report the May 16 story on the Oval Office meeting about Flynn, which he gave in an interview with Barbaro the day after Comey’s testimony. (The relevant audio begins at around 18:45):

One of the shortcomings of having the story come out like this is that things become very simple. Comey called a friend, said friend, leak memo to Schmidt, there it goes. When you hear it in that sense, it seems kind of simple … So I’m going to be a little guarded because I gotta protect my sources and methods, but I also feel like I have a duty or a need to address it because it is a public issue, and we ask people to speak publicly all the time, so we shouldn’t run from that. So I will say that coming into Tuesday, the day that I broke that story, I knew that there were memos that he had written, and I was moving toward that day writing a story that said that there were Comey memos. That was all that I knew. I thought that was a pretty good story, just the idea that Comey had created these contemporaneous memos. And in the process of moving in that direction, that morning, Tuesday morning, I found out the stuff about Flynn, and Comey, and what Trump had asked Comey to do about it. I did not know at the time that it was Comey’s intention to get a special prosecutor appointed. I did not know that until I was sitting in the hall there today [while Comey testified].

According to Schmidt, in other words, he reported the May 11 story about the loyalty dinner based on conversations with multiple sources over the course of May 10. Neither the story itself nor Schmidt’s podcast conversation with Barbaro reference anything about a memo. Indeed, while at some point, Schmidt became aware that memos existed, he says explicitly that he didn’t know anything about the content of any of those memos until the morning of Tuesday, May 16, when Richman reached out to him and read him the contents of the memo documenting the Oval Office conversation. So if Kasowitz is right, it’s not just Comey who is lying. The New York Times is lying about its reporting process too.

By contrast, if we take Schmidt and the Times at their word, there are no indications that, as Kasowitz argues, the May 11 story was sourced to a memo by Comey.

Admittedly, Schmidt’s statement that he had no access to the memo before May 16 wasn’t available on June 8, the day of Comey’s testimony and the day that Kasowitz released his first statement. But Schmidt’s previous accounts of his reporting of the May 11 story were quite available, and the June 9 episode of The Daily was released hours before Kasowitz’s second statement later that day. In any event, a good lawyer does not issue a factual statement on behalf of a client on matters about which he has no access to information that others can use to contradict him authoritatively.

In addition to Kasowitz’s questionable statements, there’s also his odd threat to file a complaint against Comey with the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Justice, along with a letter to the Senate Judiciary Committee. The grounds of the complaint are not entirely clear: as Timothy Edgar and Susan Hennessey have written, there is nothing illegal about Comey’s decision to provide the contents of an unclassified memo to the Times. The feverish excitement in the right-wing press aside, this complaint is going nowhere. The attacks on Starr for leaking (most of which lacked merit, by the way) at least alleged disclosures of grand jury information and other genuine improprieties. It’s hard to see how this complaint, by contrast, doesn’t backfire—if it materializes at all.

To summarize then, in the service of a client accused by his former FBI Director of interfering with the Russia investigation and improperly pressuring law enforcement and lying about the FBI, the President’s personal lawyer—who has Kremlin-linked clients—this week issued two factually false statements and threatened to file a “complaint” of dubious merit.

Writing about Ginsburg in 1998, the shocked young editorial writer commented:

Ginsburg may believe that publicly telling his client's story is the single most important service he can do her. But there is a good reason that defense lawyers typically avoid making public comments during criminal investigations: Anything they say can be used against their clients. When a lawyer talks about a matter at issue in a criminal probe, he risks waiving the attorney-client privilege for that issue. He also creates a public record that can be used to contradict his client's later testimony if the two are not fully consistent with one another. Ginsburg's entertaining but often contradictory indiscretions do a client such as Lewinsky no conceivable good. What's more, his public prancing between different stories suggests a disdain for the whole idea of truth, which seems to be, in his hands, whatever he feels moved to say to any given interviewer on any given day. Ginsburg is helping to destroy whatever credibility Lewinsky might have had, following her contradictory statements, to explain whether the president did or didn't violate the law. He is, thereby, doing the investigative process a real disservice.

Kasowitz should probably read this column. He undoubtedly cares nothing about the investigative process. But he’s doing his client a disservice.

By the way, someone other than Comey and the New York Times has already raised significant factual questions about Kasowitz’s account of Trump’s Oval Office meeting with Comey about Flynn. In an interview on Fox News this Saturday, Donald Trump, Jr. stated: “When [Trump] tells you to do something, guess what? There's no ambiguity in it, there's no, ‘Hey, I'm hoping.’ You and I are friends: ‘Hey, I hope this happens, but you've got to do your job.’ That's what he told Comey.”

This statement is at least in tension with Kasowitz’s declaration that “the President never, in form or substance, directed or suggested that Mr. Comey stop investigating anyone, including suggesting that that Mr. Comey ‘let Flynn go’” (sic).

The last thing Trump needs now is a defense counsel as reckless with the truth as he is.