The Barr Nomination: Weighing Norms Against Pragmatism

A president like Donald Trump, who behaves outlandishly and governs recklessly, poses unique challenges to other institutional actors. Jack Goldsmith, among others, has identified how those who who flout norms in answering the president's own norm-busting chart a dangerous path from which there will be no simple or certain return.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

A president like Donald Trump, who behaves outlandishly and governs recklessly, poses unique challenges to other institutional actors. Jack Goldsmith, among others, has identified how those who who flout norms in answering the president's own norm-busting chart a dangerous path from which there will be no simple or certain return. That's one question, but there is another: To what extent, in these extraordinary circumstances, should other institutions accommodate the intense political pressures and conflicts that this president generates? What are the risks in selecting a course meant only to minimize or contain, rather than confront head-on, the damage he is causing?

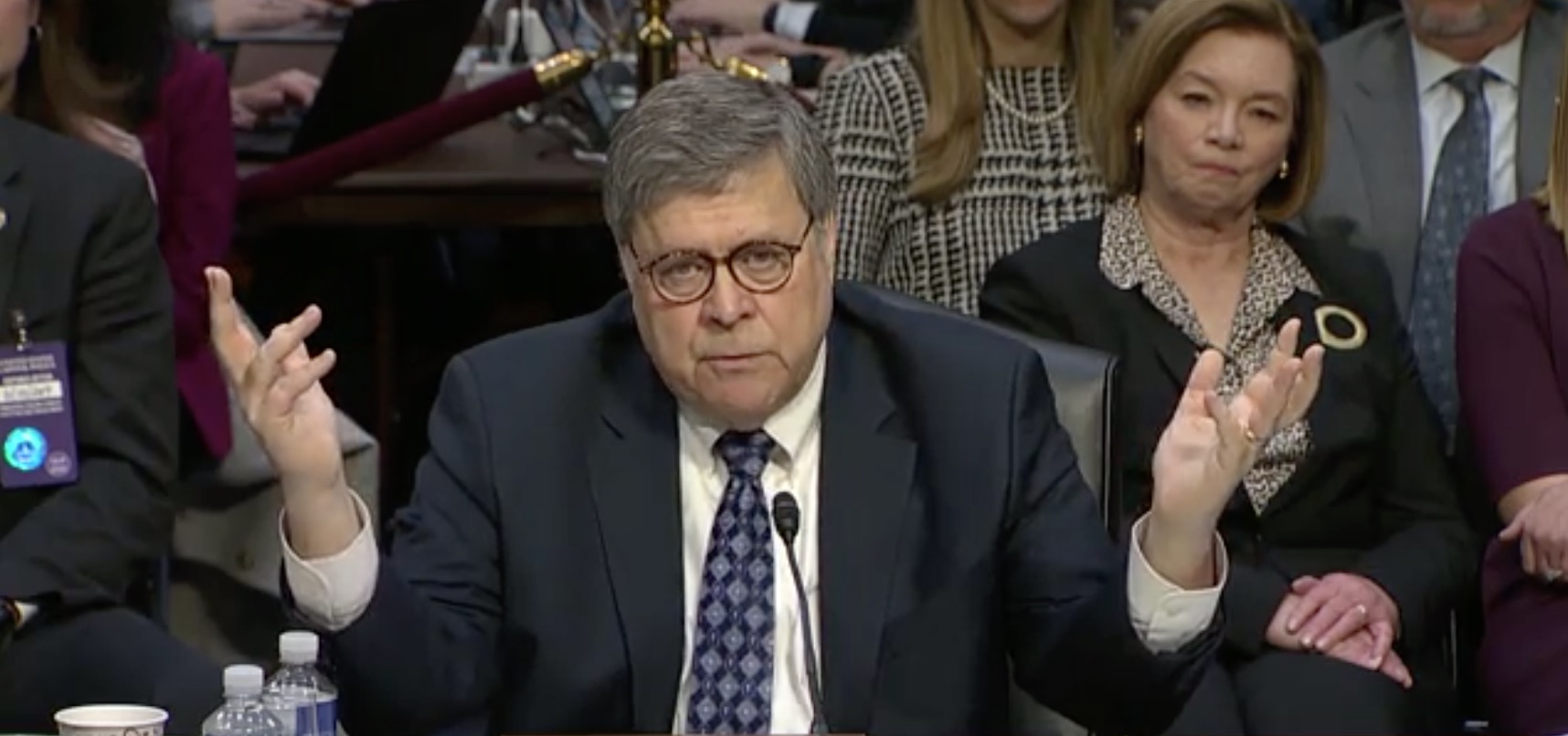

The Senate currently faces this dilemma in the case of William Barr, President Trump’s nominee to serve as attorney general. Barr, who previously headed the Justice Department under President George H.W. Bush, has taken aggressive positions on executive authority. He has exhibited so strong a commitment to those views that in June 2018 he sent the Department of Justice an unsolicited memorandum vigorously contesting at least one theory under which this president could be accountable for obstruction of justice. If Barr is confirmed, an attorney general holding these views would lead the Department of Justice under a president who is under an active special counsel investigation for obstruction and who has made other sweeping claims about the breadth of executive powers and immunities, including his “absolute” power to pardon.

Barr is a deeply troubling pick for this administration at this time. The attorney general this president least needs is one who holds the views that Barr does, and who prior to his nomination was energetically advertising them to administration lawyers. This is not all: Barr has suggested that there may be basis for concern about partisan bias in the office of the special counsel and opined that Hillary Clinton’s foundation was more worthy of investigation than Russian collusion. No doubt Donald Trump, hearing all this, was encouraged to believe that he had finally found the attorney general that he needs.

Yet some have argued that, because Matt Whitaker—the unqualified acting attorney general apparently chosen for personal loyalty and political reliability—will remain in place until a successor is confirmed, the Senate should approve the Barr nomination. Whitaker’s lack of distinction and evident unsuitability for the post would give every reason to believe that he was chosen to be Trump’s “eyes and ears” at the department, put there to keep tabs on developments dangerous to the legally embattled president. Better to take a chance, the argument goes, with a serious lawyer who has had senior government experience and maintains meaningful ties to the credentialed legal community. In effect, Trump has his critics over a barrel. Turn away Barr, and Whitaker is what you get.

The members of the “better Barr than Whitaker” school of thought will likely take some comfort from the nominee’s first day of confirmation hearings. Barr made some headway in assuaging concerns over his appointment. He denied he would be “bullied,” insisting that at this stage in his life he loses nothing by embracing “independence.” He seemed to walk back some of the concerns on his view of executive power triggered by his memorandum to the Justice Department and the president’s legal team by acknowledging that the president can criminally abuse constitutional authorities like the pardon power. In some cases, he stated the obvious—but it was reassuring to hear it, as in his commitment that he would not dismiss Mueller for other than good cause and, or that he would not allow the president’s lawyers to “correct” a draft provided to them of the Mueller report.

But the need to hear the obvious is just one more symptom of the profound problems with this presidency. What may be obvious in most governments is not necessarily or even usually so in this one.

Still, any soothing answer given by Barr will be subject to later revision, elaboration or re-interpretation. And a number of his other answers could reasonably provoke unease. Barr refused to commit to recuse in the Russia matter even if counseled to do so by the department’s ethics advisers. He was guarded in his commitment to transparency in making any report produced by the Mueller report available to the public and the Congress. He declined the invitation to defer to Mueller’s judgments, which means that it is not quite true, as he has also said, that the special counsel would be allowed to finish his work—at least as Mueller sees fit to do that work. And in his opening statement, while assuring the judiciary committee that he is committed to independent administration of the law, Barr made clear that he was speaking only of those instances “where the judgment is to be made by me.” He did not specify which categories of decisions he regards as his own and those which, on his theory of executive authority, he would refer to the president for the final decision.

The hearings so far expose the limitations of the conventional “advice and consent” format. The nominee need only get by, and usually the most general or indefinite of answers will be enough, especially on the calculation that what is “enough” must be judged by the alternative of Whitaker.

The preservation of important rule-of-law norms in the wake of this presidency depends on a number of factors and developments. But the choice of the Department of Justice’s leadership over the next two years is one of them. If the Senate proceeds with the standard “advice and consent” ritual, confirming Bill Barr in large measure on the basis of practical political considerations, the defense and reinforcement of norms could be radically weakened.

In thinking about the relationship of institutional response to the shaping of norms, it is useful to recall the controversy over President Ford’s actions in the Watergate matter. The controversy over the pardon of Richard Nixon did not simply center on the cost to the impartial administration of the law. Some critics contended that the norms at issue in Watergate, distinguishable from the crimes committed, required clear restatement. The prominent political scientist Nelson Polsby was not alone in objecting that Ford’s action “made much more confusing and difficult… the firm articulation of precisely what the norms are.” On the other hand, Ford selected as his Attorney General Edward Levi, who successfully undertook to begin restoring the confidence in the Department by a clear, public articulation of its unique mission.

In any such defense today against the collapse of rule-of-law norms, the prospect of leaving Justice Department leadership in this administration to Whitaker may well work in favor of Barr’s nomination. At the same time, the Senate would be wrong to treat Barr’s confirmation hearings as “advice and consent” in the ordinary course. It should seek to have Barr recognize that he would have additional, exceptional obligations in these extraordinary circumstances. What is needed is more than the customary oversight that Congress is always free to conduct. This attorney general, bringing these theories of executive power to this administration, should commit to a continuing and extraordinary engagement with the Congress on rule-of-law issues, including but not limited to the Russia investigation. After all, he will be serving a president who, according to his former secretary of state (and much other publicly available evidence), lacks a “value system” that includes respect for legal limits—and who “grew tired” of hearing “‘Mr. President, I understand what you want to do, but you can’t do it that way, it violates the law….’”

As Barr declared his opening statement before the committee, the country is “deeply divided” and the “American people have to know that there are places in the government where the rule of law—not politics—holds sway, and where they will be treated fairly based solely on the facts and an evenhanded application of the law.” This reasoning would seem to commit him to the highest level of transparency and accountability to the legislative branch. What the citizenry “ha[s] to know” depends on it. Where his predecessor Jeff Sessions fenced with Congress, declining to answer specific questions but hiding behind vaguely stated policy and practice rather than formal and well supported invocations of executive privilege, Barr should be asked to agree to as much of a partnership around the issues as the legislative and executive branch can ever achieve.

If Barr resists or dodges the suggestion that he has any such special obligations at this time, his nomination is reasonably opposed. If, as is likely, he is confirmed anyway, the Democratic-controlled House, if not the Senate, should establish a program of extraordinary, intense and unrelenting oversight.

As the Senate considers the Barr nomination, a similar question of the limits of political realism at the present time is playing out as the new Democratic majority weighs whether the House should move with dispatch on an impeachment inquiry. Here, too, the institution faces the tension between this realism and the importance of protecting norms. The chair of the House judiciary committee, Jerrold Nadler, has stated that the time is not ripe for a formal impeachment inquiry. He termed it “premature” and said at the present time there is no “case” that the president is subject to impeachment. He has also emphasized the difference between the commission of impeachable offenses and any such offense so serious that it would warrant impeachment. He has worried openly about the perception within a sizeable part of the electorate that the Democrats would be driven by partisanship in instituting an impeachment process.

As Nadler’s comments show, the Democratic leadership is apparently and commendably concerned with acting responsibly in dealing with Donald Trump’s impeachable offenses, and this responsibility also involves protecting against any fair charge that Democrats are just planning for Trump’s political ruin. The clear risk is that a reluctance to engage squarely with the questions of impeachment puts in doubt the vitality of norms critical in constraining executive abuses of power. The norms Trump famously disdains, and in specific instances violates, are guardrails against such abuse: It is their systematic disregard that justifies inquiry into the commission of impeachable offenses. The House can address the anxieties about the initiation of the impeachment process by the exercise of due care and good judgment in going about this business; but it need not hold off on a formal impeachment inquiry that, while it may be politically hazardous, is not premature.

The question of the president’s fitness to hold office is not up to Bob Mueller or to public opinion measured by polling at any point in time, and it is not only or mainly an election year issue to which the nation can turn as the political seasons heats up. If, because the politics in a divided country are fraught, this president’s behavior cannot be met with a responsible, well-structured impeachment process, then the country will have gone well along the way toward a new, poorly defined but perilous normal.

In both the Senate’s confirmation of Barr and the House’s conduct of inquiries into presidential misconduct, political realism will inevitably exert some pressure on the institutional choices defined and then made. The question is how much—and in the Trump presidency, the answer requires subordinating these calculations to the imperative of protecting the rule of law, reinforcing critical norms of executive branch behavior and facing unflinchingly the question of Donald Trump’s fitness to hold office. The House should not be reluctant to turn to the process the Constitution provides for extraordinary circumstances such as these. And the Senate should demand more than general reassurances in a confirmation process that must be more than just business as usual.