Belarus and the Hijacking of Ryanair Flight FR4978: A Preliminary International Law Analysis

From the perspective of international law, it is difficult to overstate the seriousness of Belarus’s actions.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

News broke on Sunday about a midair diversion of a plane flying over eastern Europe, followed by an emergency landing. This itself would be mildly significant, but when the facts as reported are known, the story attains wider and more dramatic importance about several issues: the freedom of political protest, authoritarian rule in isolationist parts of the world and the rule of law in international affairs.

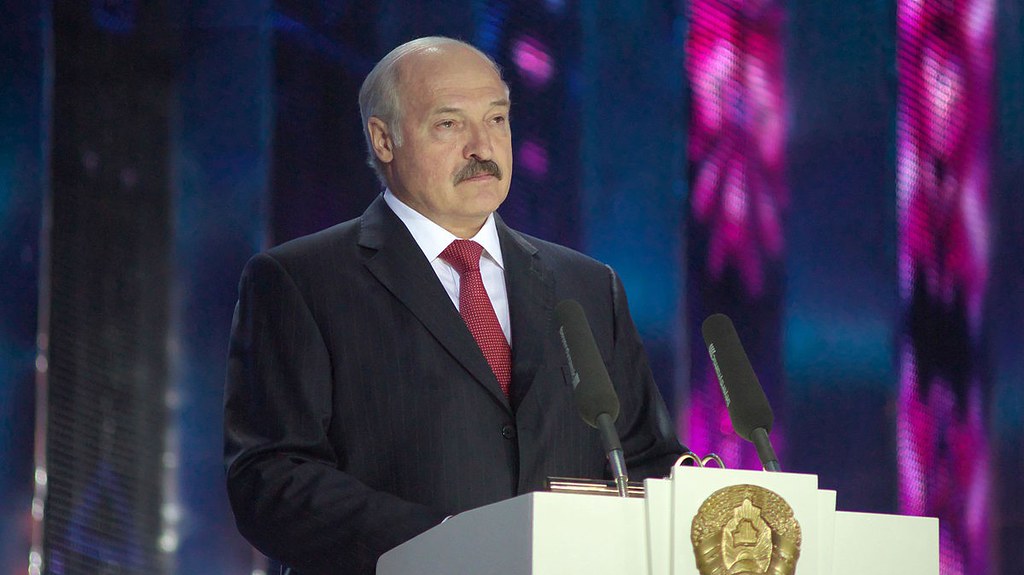

According to media reports, on the afternoon of May 23, Ryanair flight FR4978 was en route from Athens, Greece, to Vilnius, Lithuania. The aircraft—bearing tail number SP-RSW—was registered in Poland. One of its passengers was Roman Protasevich—a Belarusian journalist and dissident who played a key role in protests against Alexander Lukashenko’s regime in the wake of the contested 2020 presidential elections. Sofia Sapega, a Russian law student and his partner, was traveling with him.

Two officers of the Belarusian secret police, the KGB, were also onboard. Once the plane was in Belarusian airspace, those officers told the pilot of flight FR4978 that there was an explosive device on board, and that an immediate emergency landing was required. At this point, a Belarusian Air Force MiG-29 appeared alongside and “escorted” the aircraft—not to the nearest airport in Vilnius, but to Minsk, Belarus. On landing, Protasevich and Sapega were detained. Six hours later, flight FR4978 was allowed to resume transit to Vilnius—minus six passengers on its original manifest, including Protasevich and Sapega. Certain reports have offered harrowing accounts of Protasevich’s reaction. Told the aircraft had been diverted, he shook and held his head in his hands. While being led away in Minsk, he was reported to have said, “I’ll get the death penalty here.”

There was, of course, no explosive device on board flight FR4978. The claim that there was appears to have been a ruse by Belarus to force the aircraft to land in Minsk so that Protasevich and Sapega could be arrested. For its part, Belarus has admitted there was no bomb—but rather than own up to its actions, it has concocted a narrative whereby Hamas made the threat in order to secure a cease-fire with Israel in Gaza. Given that the actual cease-fire was obtained on May 21—two days before flight FR4978 took off—this story seems, to put it mildly, wildly implausible.

From the perspective of international law, it is difficult to overstate the seriousness of Belarus’s actions. While international law as a whole is often criticized as vague, unenforceable, and prone to manipulation or convenient reinterpretation by powerful actors, not all of it operates that way. Some regimes of international law, by the agreement of states, are quite straightforward. They have clearly defined obligations to defend interests essential to the functioning of international society on a day-to-day basis, combined with appropriate routes for adjudication. One such regime is the network of treaties governing international civil aviation—most notably the 1944 Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation and the 1971 Montreal Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Civil Aviation, both of which Belarus is a party to.

In examining those treaties, one can immediately see the outline of a powerful case as to why Belarus’s actions violate international law. Article 1(1)(e) of the Montreal Convention creates an international crime where a person unlawfully and intentionally “communicates information which he knows to be false, thereby endangering the safety of an aircraft in flight.” Secondly, per Article 10 of the Montreal Convention, a state must “in accordance with international and national law, endeavour to take all practicable measures for the purpose of preventing the offenses mentioned in Article 1.”

It follows that, in contriving an emergency landing of flight FR4978 off the back of a fake bomb threat, Belarus committed an outrageous breach of the Montreal Convention.

In the ordinary course of events, Poland, as the flag-state of the aircraft, or any of the Montreal Convention’s 186 other relevant member states, could bring a case against Belarus before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague. But that is precluded in this case by the fact that, on signature, Belarus (then the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic) put in a reservation to Article 14—the Montreal Convention’s dispute settlement provision, which provides for ICJ jurisdiction. Hence, if a state attempted to bring a case against Belarus, the ICJ would most likely dismiss it for lack of jurisdiction.

But not all avenues are closed. Belarus failed to make a similar reservation to Article 87 of the Chicago Convention, providing that any dispute under that treaty can be referred to the Council of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)—the specialized agency of the United Nations charged with coordinating civil air travel—with any decision of the ICAO Council subject to appeal before the ICJ. And, moreover, by breaching Article 10 of the Montreal Convention in persuading flight FR4978 to land, Belarus appears to have equally breached Article 3bis(b) of the Chicago Convention. That provision provides that in exercising its right to ground an aircraft in transit over its territory, a state can only do so by resorting to “appropriate means consistent with relevant rules of international law.” Poland or any of the other 191 members of the Chicago Convention would conceivably have standing to commence such proceedings.

What we therefore see here is a comparative rarity in international law—a clear breach of two respected international treaties by a state, combined with a clear route to the jurisdiction of an international court or tribunal. The remedy under international law is similarly clear. Poland, as the flag state of the aircraft—and, in international law terms, the victim of Belarus’s unlawful act—is entitled to full reparation. Other states may have similar claims. As the forerunner of the ICJ, the Permanent Court of International Justice, put it in the Chorzów Factory case in 1928, this means that Belarus “must, as far as possible, wipe out all the consequences of the illegal act and reestablish the situation which would, in all probability, would have existed if that had not been committed.”

In bluntly practical terms, this means that Protasevich and Sapega must be released from Belarusian custody and allowed to continue to Vilnius—as they would have done if Belarus had not behaved as it did. That Protasevich is a Belarusian national does not alter this conclusion. For Poland (or any other qualifying state) to be made whole in the Chorzów Factory sense, he must be permitted to leave Belarus. There is precedent for this, with Russia being made subject to similar orders by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea at the request of the Netherlands in the Arctic Sunrise case in 2013. That case concerned the interception of a Dutch-flagged Greenpeace vessel in the Russian exclusive economic zone with Russian nationals aboard.

Of course, this is merely an early analysis of how one international controversy appears to involve a violation of international law in a manner that can be brought before the ICJ. Various foreign ministries will have commenced their own analyses already, and more articulated cases may well be produced in the days and weeks to come. Some may find grounds for international wrongfulness beyond the civil aviation context—most likely concerning the human rights of Protasevich and Sapega. Of course, this scramble to find an appropriate jurisdictional angle on the case sheds light on one of the persistent weaknesses of international law—its lack of compulsory dispute settlement and enforcement mechanisms. As Lawfare readers know, there is often no real way around this reality: international law is rooted in concepts of voluntarism and cooperation, which are usually the first things to go when dealing with any inter-state dispute.

One thing, however, is clear. Belarus’s decision to ground flight FR4978 on a pretext to take a dissident and his partner into custody should cause profound disquiet within the international community and invite immediate consequences. The network of agreements governing international civil aviation is rightly seen as one of the most significant achievements of the wave of post-1945 treaty-making that converted international law from a relatively narrow and ad hoc discipline into the comprehensive rules-based system of today. Moreover, although somewhat truncated in the era of COVID-19, air travel is a central part of international commercial life, in much the same way as international shipping, which is regulated by a similarly dense network of international treaties, most notably the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea. Were the international community to tolerate aerial piracy, then other state actors could well form the view that such action is a permissible way of seizing political dissidents (or any other individual they want to detain, for that matter). Regardless of the formal jurisdictional question, that cannot be permitted if states want to maintain safe and reliable international air travel as a feature of the international system.

In the first instance, the burden falls greatest on the EU. Flight FR4978 was an intra-EU flight by an EU-flagged plane operated by an EU-domiciled airline. For the EU, this question is more than about ensuring freedom of overflight in the general sense. It is about its capacity to protect those who operate within its Member States from a rogue and isolated state on the bloc’s eastern border. If the EU cannot do that, then one begins to wonder what its value is, in terms of collective security.

Early signs that the EU and the wider international community is taking this seriously are encouraging. The president of the EU Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, immediately described Belarus’s actions as a “hijacking”. The EU summoned the Belarusian ambassador to the EU, presumably in anticipation of a formal diplomatic demand or demarche (the expulsion of the ambassador via a declaration of persona non grata or even the severing of diplomatic relations being a measure of last resort). Sanctions—additional to those imposed in relation to the 2020 elections—are also being discussed, and are expected to be announced on the evening of May 24. At the same time, the parliamentary foreign affairs committees of a number of NATO and EU states have called for the stopping of international flights over Belarus, an investigation by ICAO and the release of Protasevich and Sapega. Some states are not waiting. The United Kingdom, for example, has suspended U.K.-flagged flights to and over Belarus, and has revoked landing rights for Belarus’s national carrier, Belavia. Across the Atlantic, the U.S. has also expressed grave concern, with Secretary of State Antony Blinken also calling for an international inquiry and pledging support for collective action. ICAO itself has also expressed its willingness to undertake further action if asked, in the form of a potential investigation.

Depending on the scale of these sanctions and other responses, the international community backlash to the detention of Protasevich and Sapega will leave Belarus more isolated from Europe than it already is, and generally cut off from the central and western parts of the continent. While any sanctions will generally be targeted at individuals that the EU considers responsible for the diversion of flight FR4978 and the detention of Protasevich and Sapega (with the exception of President Lukashenko himself, who holds head of state immunity), it will be impossible to insulate ordinary people entirely from the economic impact of such measures. This could conceivably prompt further protests from the Belarusian citizenry, and further crackdowns from the government.

One wonders, however, if “grave concern” will be enough to secure Belarus’s compliance with international law – even if backed by sanctions. If, as stated, international law’s principal method of enforcement is withdrawal of the benefits of international society, then what is to be done when a particular state decides it is content to go without those benefits? Certainly, in the wake of the 2020 elections, following which Lukashenko is widely perceived to have used state violence to remain in office, the Belarusian government has made it perfectly clear that it will not bow to international pressure to change its behavior—though it remains sensitive to the Russian government’s opinion. Belarus is far from a “hermit kingdom”—as Albania once was, and North Korea still is—but there is little doubt that it is steadily turning inward, perhaps irrevocably so, and that international action may hasten this process.

Whatever the answer, the international community should not balk from trying to bring Belarus into line here via coordinated political and legal means. If the international community fails to take action, other states, who are doubtlessly watching carefully, may get the idea that this kind of behavior will be generally tolerated without serious repercussions. Refusal to act may therefore usher in a new reality of international air travel—one in which airlines either refuse to fly over certain regions, or will not carry known political dissidents on their aircraft, for fear of state-backed hijacking.

.jpg?sfvrsn=5a43131e_9)