Biden Brings Semiconductors to the Forefront of Americans’ Minds

On technology, President Biden’s State of the Union address sent a clear message: U.S.-China

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

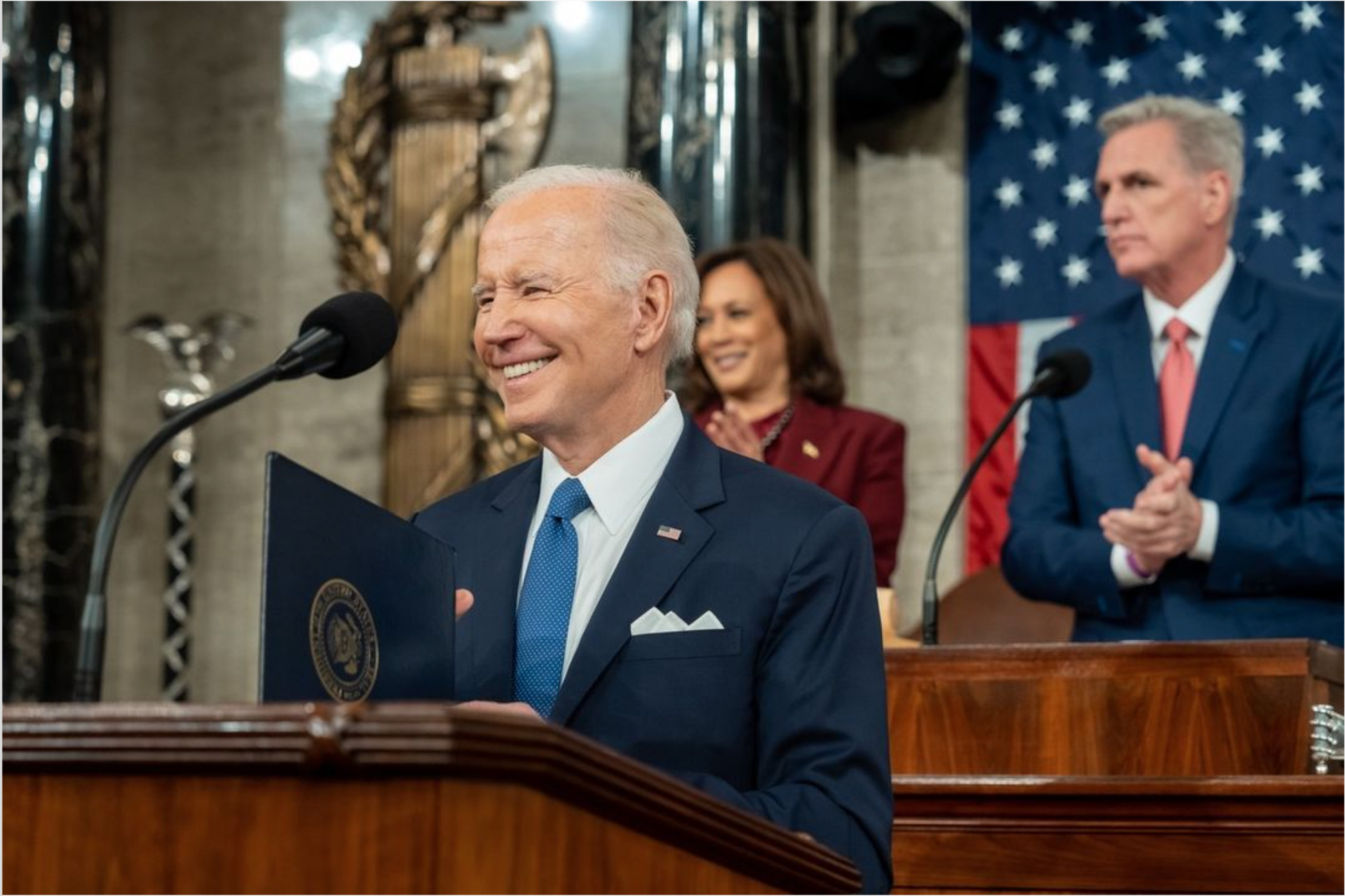

President Biden’s State of the Union (SOTU) address brought semiconductors to the forefront of the nation’s attention. Heightened U.S.-China relations, widespread chip shortages, and the weaponization of supply chains for geopolitical purposes have moved semiconductors to the top of U.S. policymakers’ agenda for the first time in decades. On Feb. 7, President Biden attempted to convince the American people that they too should care about the semiconductor industry. Adding to a series of recent semiconductor initiatives, Biden’s SOTU address made chip issues personal for everyday Americans in a clear effort to solicit public support for the administration’s technology agenda.

Biden’s first reference to semiconductors was made just 10 minutes into the address, explaining them in nontechnical terms as “small computer chips the size of a fingerprint.” Rather than highlighting semiconductors’ importance to advanced electronic warfare systems, autonomous drones, the Javelin missiles that have undermined Russian tanks in the Russia-Ukraine war, or other aspects of national defense, Biden stressed that chips power the consumer products on which Americans depend, “from cellphones to automobiles and so much more.” Chips, in other words, fuel economic prosperity and everyday American life.

Biden next appealed to Americans’ sense of pride to convey the urgency of the semiconductor challenge. The president observed that semiconductors “were invented in America” and that the U.S. “used to make 40 percent of the world’s chips.” The United States, however, “lost its edge” over the past several decades, currently producing only 10 percent of the global semiconductor supply. This is not without consequence: America’s waning domestic semiconductor infrastructure carries repercussions that affect real people.

Overseas chip factory closures during the coronavirus pandemic gave Americans an initial taste of the size and significance of their stake in the semiconductor industry. As Biden noted, chip shortages caused higher prices for automobiles, refrigerators, and cellphones, and less American manufacturing resulted in widespread layoffs. The chip shortage cost the auto industry an estimated $210 billion in revenue in 2021. While these effects are certainly important, the ramifications of coronavirus-related chip shortages would pale in comparison to those associated with a future conflict, natural disaster, or related contingency in Asia.

Complicated business models and the expertise required to make chips have afforded a handful of countries in East Asia—Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, and China—an outsized influence over the semiconductor industry and contributed to the emergence of a highly concentrated and fragile semiconductor supply chain. Beginning in the early 1990s, the capital- and research-intensive nature of semiconductor manufacturing compelled many firms (particularly U.S. and European ones) to abandon the foundry business and focus exclusively on chip design or the development of chip-making equipment.

Consequently, most of today’s top chip design companies rely on manufacturers in Taiwan and South Korea, which are home to approximately 80 percent of the global semiconductor foundry market. Two firms, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) and South Korea’s Samsung, account for more than 70 percent of semiconductor manufacturing and are the only suppliers of cutting-edge chips. In particular, the volume of semiconductor chips made in Taiwan accounts for over 50 percent of the global total, and TSMC produces 90 percent of the world’s most advanced chips.

Though TSMC and Samsung are the dominant manufacturers of semiconductors, they rely heavily on equipment and machinery from the United States, Europe, and Japan. Five semiconductor capital equipment vendors—three American, one European, and one Japanese—dominate the market, and Netherlands-based ASML is the only company in the world that makes the extreme ultraviolet lithography technology required to manufacture the most advanced chips.

U.S. industry remains a leader in global chip sales, holding nearly 50 percent of the annual global market share. Global sales market-share leadership fosters innovation and supports the United States’s highly competitive position in research and development efforts. The U.S. is also a leader in semiconductor design capabilities, averaging 49 percent of global market activities and accounting for the largest share of the global design workforce.

The problem, as Biden alluded to in his SOTU address, is that the U.S. lacks the infrastructure, capacity, and expertise to offset a loss of access to Asian semiconductor manufacturing. A recent Boston Consulting Group and Semiconductor Industry Association study estimates that a one-year disruption to Taiwan’s production of semiconductors would cause a $490 billion drop in revenue for electronic-device makers alone.

This challenge, coupled with China’s renewed assertiveness and strategic technological rise, serves as the impetus for a flurry of recent U.S. legislative and executive action intended to boost domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity, strengthen supply chains, and create jobs. President Biden signed the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act into law in August 2022. The act includes a $39 billion manufacturing incentive program aimed at reinvigorating the U.S. chipmaking ecosystem across a range of technologies, from large-scale fabs to manufacturing equipment and supplies. The CHIPS Act also includes a complementary 25 percent advanced manufacturing investment tax credit designed to lower the cost gap between investing in the U.S. and investing abroad, as well as funding for semiconductor research and workforce development.

CHIPS Act funding is insufficient to remedy all of the U.S.’s challenges, and successful implementation hinges on proactive government oversight. But the CHIPS Act is making an impact. Since the act’s introduction in June 2020, semiconductor companies have invested more than $180 billion in the U.S., launched 46 new projects including the construction of new fabs, and created more than 200,000 jobs. The CHIPS Act contributed to TSMC’s December 2022 plans to open a second chip plant in Arizona, raising its investment in the state to $40 billion, one of the largest foreign investments in U.S. history. Among the crowd at Biden’s SOTU address was Paul Sarzoza, the president and CEO of Phoenix, Arizona-based Verde Clean. The company’s biggest customer is TSMC.

The CHIPS Act and related initiatives constitute one pillar of Biden’s technology agenda focused on promoting American competitiveness by leveraging the country’s strengths. A second pillar of the president’s agenda focuses on protecting U.S. technology and restricting China’s access to cutting-edge capabilities.

In October 2022, the Commerce Department introduced a sweeping set of export controls aimed at eliminating Chinese firms’ ability to manufacture advanced computer chips. The controls specifically target graphics processing units, an advanced type of semiconductor that could contribute to China’s artificial intelligence-enabled surveillance systems and military modernization efforts, and certain types of chip production equipment. The export controls also include novel provisions that bar U.S. persons from providing maintenance, equipment upgrades, and other services to Chinese firms without a license.

October 2022 marked a significant shift in U.S. policy vis-a-vis China. Past U.S. efforts intended to slow China’s technological advancement. The Biden administration’s latest restrictions go a step further, aiming not just to degrade China’s progress but to freeze it altogether by denying China access to the components, equipment, and talent necessary for continued technology advancement. This approach ushers in a new phase of technological competition with China, but unilateral U.S. action is unlikely to succeed.

Effective export controls require the support and cooperation of U.S. allies to prevent the backfilling of U.S. technology that can no longer be sold to China. The Netherlands and Japan, two crucial allies, reportedly agreed to join the United States in implementing technology restrictions. But it is not yet clear how the Dutch and Japanese governments may respond to pushback from industry partners who are hesitant to get on board and abandon the lucrative Chinese market. Biden’s ability to garner sufficient support for export controls and anticipated outbound investment restrictions will test the long-term viability of the administration's “protect” pillar.

Until now, a conscious attempt to involve the American public has been noticeably absent from the Biden administration’s technology strategy. Previously, the White House made little effort to convey the significance of U.S.-China competition and emerging technologies in digestible terms and explain how a failure to both promote and protect U.S. competitiveness could impact Americans’ everyday lives. Biden’s SOTU address thus seemed to introduce a third pillar to the administration’s existing approach to technology: public engagement.

Biden’s calls to increase domestic semiconductor manufacturing and secure supply chains echo sentiments from last year’s SOTU address, in which the president applauded American multinational technology corporation Intel for its investments in the U.S. semiconductor infrastructure. This year’s prioritization of job creation, emphasis on chips’ relevance to everyday American life, and promise to “transform the heartland” by building semiconductor fabs signals a shift in tone. The American people are key stakeholders in the semiconductor industry, and U.S.-China competition is here to stay. Public support will be a crucial component of any successful American technology strategy.