Bipartisan Agreement on Election Security—And a Partisan Fight Anyway

The good news is that national security bipartisanship in Congress lives. The bad news is that the only place it lives is in the pages of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on Russian election interference.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The good news is that national security bipartisanship in Congress lives. The bad news is that the only place it lives is in the pages of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on Russian election interference.

The report, released on July 25, offers a thorough—if often redacted—assessment of Russian threats against U.S. voting infrastructure in 2016. It paints an alarming picture of the scope and scale of Russia’s efforts and an equally alarming picture of the degree of vulnerability that persists in U.S. election systems heading into the 2020 election. While it describes no evidence of vote tallies being manipulated or votes being changed, it does describe how “Russian government-affiliated cyber actors conducted an unprecedented level of activity against state election infrastructure in the run-up to the 2016 U.S. elections.” The report is a serious work and reflects a level of bipartisan cooperation that is vanishingly rare in Washington these days. The committee and its staff should be commended for that.

The problem is that while both sides appear to agree on the nature of the threat, Republicans and Democrats remain sharply divided over what, if anything, to do about it. And that division became painfully apparent the very day the committee released the report.

It is not a complete surprise that the week of Robert Mueller’s testimony before the House of Representatives would devolve into a pitched battle over election security. Everything is partisan these days. Why not election security? In the wake of Mueller’s testimony, Democrats sought to use the moment to push election security legislation, thus putting pressure on Republican senators to support it or look like they weren’t taking the threat seriously. And Republicans held out, thus creating a sharp partisan divide over the one part of the Trump-Russia issue over which everyone purports to agree.

Robert Mueller has foot-stomped what everyone—except President Trump—takes as a given. The Russian government “interfered in the 2016 election in sweeping and systematic fashion” and that fact “deserves the attention of every American,” he announced during his surprise May 29 press conference. Testifying before the House Intelligence Committee on July 24, he declared, “I have seen a number of challenges to our democracy. The Russian government’s effort to interfere in our election is among the most serious.”

As if to draw a line under Mueller’s argument, the Senate Intelligence Committee report on “Russian Efforts Against Election Infrastructure” came out the day following his testimony. The 67-page document is the first volume of a multivolume set of reports the committee has announced it will release over the coming months—the results of its independent investigation into Russian election interference.

The report’s findings are generally bipartisan. The document includes additional views by a handful of Democrats: Sen. Ron Wyden wrote separately, and Sens. Kamala Harris, Michael Bennett, and Martin Heinrich added “Additional Views” as well. The latter three senators’ statement amounts to a general endorsement of the report as “an important contribution to the public’s understanding of how Russia interfered in 2016,” though the three “do not endorse every recommendation in the Committee’s report.” In particular, they single out state-level vulnerabilities to election meddling—the same objection noted in much stronger language by Wyden, who writes that he “cannot support a report whose top recommendation is to ‘reinforce[] state’s primacy in running elections.” Wyden argues instead that Congress should take charge of regulating federal elections and voices concern about the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) ability to identify manipulations of voter registration databases and vote tallies. With the exception of Wyden, though, most of the report has the support of 14 members of the committee.

All of which would make one think that the result might be, well, bipartisan legislation to address issues the committee identifies. Yet within a day of the document’s release, Senate Republicans were squelching legislative efforts to address some part of the nation’s vulnerability to electoral interference—and Democrats were crying foul.

In this post, we offer a summary of the findings of the Senate Intelligence Committee report, as well as summaries of the four pieces of legislation the Senate has held up and an account of the arguments both sides are advancing with respect to those pieces of legislation. The idea is to illuminate both the areas of bipartisan agreement and the areas of remedial dispute.

The Report Itself

First things first: The committee asserts it “has seen no indications that votes were changed, vote-tallying systems were manipulated, or that any voter registration data was altered or deleted.” The interference described in the report is more along the lines of what one expert described as “reconnaissance,” an effort to “map” election infrastructure in possible preparation for a later attack. That said, the report includes the ominous caveat that “the Committee and [intelligence community]’s insight is limited” on this question.

The bulk of the report contains a play-by-play of Russian activities and the federal government’s attempts to counter them. The first evidence that the Russian government was scanning state election systems appeared in the summer of 2016, the committee writes. According to the testimony of Former Special Assistant to the President and Cybersecurity Coordinator Michael Daniel, over the course of August 2016 the federal government became confident that the network activity represented a regular Russian probe of state election infrastructure, voter registration databases and other related infrastructure.

The first instance took place in July 2016, when Illinois discovered “a large increase in outbound data” on a voter registry website, which sparked an FBI investigation that identified some number of suspect IP addresses. In response to a request from the DHS, 20 states reported that at least one of the suspected IP addresses had interacted with their networks, adding up to 21 states reporting Russia-linked cyber activity. At one point in a largely redacted section, the report includes a DHS conclusion that seems to characterize the scanning: “[T]he searches [were] done alphabetically [and] probably included all 50 states, and consisted of research on ‘general election-related web pages, voter ID information, election system software, and election service companies.’”

The committee notes that the “DHS was almost entirely reliant on states to self-report scanning activity”: The department was operating with limited and sometimes uncertain information throughout this period, due in part to the range of state and local governments involved. In one footnote, the committee flags that state and local administrators are in a better position to carry out comprehensive cyber reviews but lack the expertise or resources to do so. Those resources and expertise can be found in the federal government, but the intelligence community can see only limited information.

This uncertainty pervades the report. In gauging how many states were targeted, the committee writes, the “DHS acknowledged that the U.S. Government does not have perfect insight, and it is possible the [intelligence community] missed some activity or that states did not notice intrusion attempts or report them.” Nevertheless, the committee writes that evidence suggests all 50 states were targeted. This conclusion is bolstered in part by the fact that neither the committee nor the intelligence community could discern a pattern as to which states reported scanning activity; the apparent randomness, the committee suggests, contributed to the DHS assessment that Russia had attempted to intrude on all 50 states. Other evidence supporting this assessment apparently developed later in 2018, but it is redacted.

The committee agrees with the Jan. 6, 2017, Intelligence Community Assessment that the types of systems that were targeted or compromised by the Russians were not involved in vote tallying. But Russian cyber actors gained access to election infrastructure systems across two states and successfully extracted voter data: In Illinois, for example, they accessed as many as 200,000 voter registration records and successfully compromised databases containing records of 14 million registered voters. No evidence was found that the cyber actors deleted or changed voter data, although they were in a position to do so. While Illinois is the only state identified by name in the report, a lengthy table included in the report lists the details of cyberattacks on the 20 other states that self-reported scanning activity to the DHS. (CNN reporter Kevin Collier has identified several of the unnamed states on the basis of the descriptions of the cyber activity provided in the report.)

The report also includes two “Unexplained Events,” listed as “cyber activity” in an additional state not on the list of self-reported states, as well as one state included on the list; the first is entirely redacted, and the DHS had “low confidence” that the second was attributable to Russia.

Additionally, the report contains sections—many of them heavily redacted—on additional Russian efforts. One section seems to indicate that cyber actors scanned a commonly used vendor of election systems. Another section states that the Russian Embassy made formal requests to observe the 2016 elections with the State Department, while it also reached outside diplomatic channels in order to secure permissions directly from state and local election officials. The intention here is not clear. Another section points to a possible misinformation campaign engineered by Russia regarding voter fraud in one of the self-reported states.

The committee’s overall conclusion is that the intentions behind Russia’s interference with the U.S. election infrastructure are still unclear. The committee presents several theories: Russia might have intended to exploit vulnerabilities during the 2016 elections but later decided, for unknown reasons, that it would not proceed; Russia might have sought to gather information on election infrastructure “in the conduct of traditional espionage activities”; or Russia might be holding a catalog of options for later use. In an overarching sense, the intelligence community assesses that the goal was to undermine the “integrity of elections and American confidence in democracy.” DHS representatives who spoke to the committee expressed widespread concern regarding the possibility of creating chaos on Election Day.

Cooperation between the DHS and the states did not run smoothly. During the summer of 2016, the committee writes, the federal government treated the threat as it would if it were “a typical notification of a cyber incident to a non-governmental victim,” before shifting toward more extensive outreach toward the states in the fall. But after DHS outreach, states bristled in response to a perceived “federal takeover of the election system.” In particular, the idea of designating election systems as critical infrastructure was met with resistance.

Not only were the states unclear on the nature and extent of the threat they were facing, but they did not find out until after the election about the possibility of their systems being targeted. Some state officials told the committee they learned for the first time of Russian scanning of election systems from press reports or a June 2017 open hearing of the Intelligence Committee. In certain cases, the DHS notified state officials responsible for network security of the threat but did not notify election officials. Some state officials falsely assumed they were not on the list of targeted states because the DHS had not directly notified their offices.

On a more positive note, however, the report states that cooperation between DHS and state officials improved by early 2018, with positive interactions that “increased trust and communication between the federal and state entities.” The DHS has offered a range of assistance to states, falling under two general categories: remote cyber hygiene scans, and on-site risk and vulnerability assessments. According to the agency, by October 2018, 35 states, 91 local jurisdictions and eight election system vendors signed up for remote persistent scans, and 21 states, 13 localities and one election system vendor had on-the-ground vulnerability assessments.

The committee concludes its report with seven recommendations for the federal and state governments to guide their approach to cybersecurity in election infrastructure. Significantly, the first recommendation is to reinforce that states have the primary role in running elections and that “the federal government should ensure they receive the necessary resources and information.”

The report promptly follows up with four prongs for building a stronger defense. Part I involves effective communication to adversaries that the U.S. government will consider an attack against its election infrastructure as a hostile act and will respond against such an act in a way that “send[s] a clear message and create[s] significant costs.” This principle of deterrence should be included in an overarching cyber doctrine, which should serve as the basis for a discussion with allies about new cyber norms. Part II tackles the improvement of information gathering and sharing on threats. Though this section is partially redacted, the report states that this objective would be achieved by investing in the improvement of both technical capabilities for attribution and communication channels between federal and state governments. In Part III, the committee offers suggestions to both state officials and to the DHS, urging them to make cybersecurity a higher priority for election infrastructure. Finally, Part IV calls for the replacement of outdated and vulnerable voting systems and sets forth steps to secure the vote.

Because states have alleged that cost is the main hurdle to improving cybersecurity, the committee recommends that the Election Assistance Commission report how the $380 million in funds appropriated by Congress in March 2018 were being used. The report argues that states should be able to use funds for the replacement of outdated voting equipment, hiring additional information technology staff, updating software or contracting vendors to provide cybersecurity services. In a closing flourish appropriate for a heavily redacted document, the committee’s last recommendation is almost entirely blacked out: The senators recommend that the government build something “credible,” but the substance of what is to be built and why has been redacted.

Legislative Gridlock

Given the committee’s bipartisan findings on these matters, one might think that members could also work closely together on remedial legislation. After all, on a bipartisan basis, committee members agree that there’s a serious problem, that it has been exploited in a dangerous fashion by one foreign adversary, and that we are vulnerable to future and worse interferences in the future. Yet even as the committee was releasing its report, the Senate was also unable to move legislation on election security issues. This week’s Senate controversy centered on four such bills, not all of them related to state voting infrastructure.

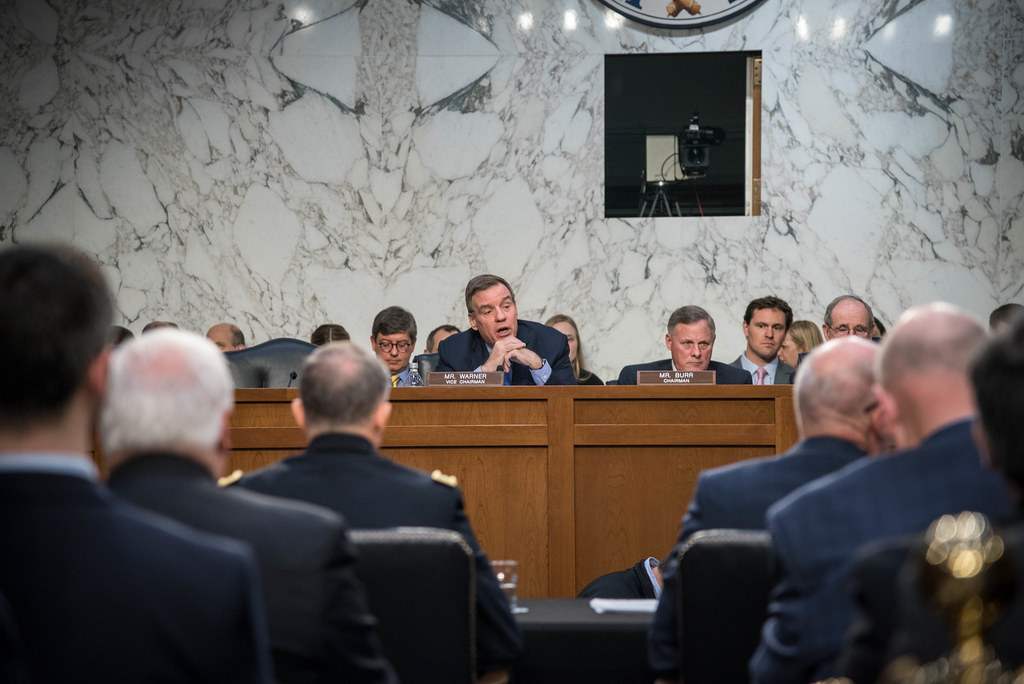

The first is the Foreign Influence Reporting in Elections (FIRE) Act, S. 1562 (later reintroduced as S. 2242). Sponsored by Sen. Mark Warner, the ranking member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, the FIRE Act would require candidates for federal office and their committee staff to report to the Federal Election Commission (FEC) and the FBI any contacts with foreign nationals offering contributions, information or services. Anyone who knowingly and willfully violates this reporting obligation would be subject to a criminal penalty of up to five years in prison and a $500,000 fine.

The second, the Duty to Report Act, S. 1247, covers similar territory. Sponsored by Sen. Richard Blumenthal, the Duty to Report Act has an identical companion bill, H.R. 2424, which is sponsored by Rep. Eric Swalwell, Blumenthal’s Democratic colleague in the House. Like Warner’s proposal, the Duty to Report Act would obligate political committees to report to the FEC any offers of prohibited contributions—a term it defines to include offers of nonpublic information relating to other candidates—from foreign nationals. In addition, it would require candidates, political committees, close family members of candidates, and individuals affiliated with a campaign to report to the FBI any offers of prohibited contributions from foreign nationals. Knowing and willing violations of this latter obligation would once again trigger criminal penalties, including up to two years in prison.

The third, the Senate Cybersecurity Protection Act, S. 890, specifically relates to the Senate’s own internal cybersecurity protections. Sponsored by Wyden alongside several Senate Republicans, including Sen. Tom Cotton, the act would empower the Senate sergeant-at-arms to use its resources to assist Senate staffers with securing their own personal communications devices and accounts against hacking and other forms of cyberattack, at the request of relevant Senate officials. It would also direct the comptroller general to prepare an annual report on cybersecurity and surveillance threats to the legislative branch, including statistics on cyber attacks and other incidents targeting the personal communications of senators, their family members and staff.

The fourth, the Securing America’s Federal Elections (SAFE) Act, H.R. 2722, is arguably the most comprehensive of the four. Passed by the House of Representatives on June 27 on a party-line vote, it introduces several changes to the legal requirements that federal law already imposes on the conduct of federal elections by state and local officials. First, it would require the use of “individual, durable, voter-verified paper ballot[s]” in all federal elections, beginning in 2020. To ensure implementation, it also calls for a number of related studies and authorizes grants to state and local officials to support this change. Second, it would add election security to the mandate for the existing federal Election Assistance Commission (EAC) that advises state and local officials on election-related issues and make certain related changes to its structure and the related dissemination of “requirements payments” to eligible states. Third, it would require state officials to conduct a “risk-limiting audit” of every federal election using manual tabulation of ballots, a report on which would be published before any final election results are certified. To facilitate this, it also provides for federal reimbursement of any related expenses. Finally, it imposes a number of new cybersecurity-related requirements on various election-related technology and imposes related reporting requirements—including that all voting machines used in U.S. elections be manufactured in the United States by 2022.

To fund these changes, the legislation also authorizes substantial appropriations, including $600 million for fiscal year 2019 and then $175 million for each subsequent election year through 2026. (Notably, House Republicans have largely supported a separate election security bill, the Election Security Assistance Act, H.R. 3412, which would make several similar changes but would remove many of the federal requirements that the SAFE Act would impose and reduce the appropriated funds to just $380 million for the 2020 elections.)

Senate Democrats kicked off the debate on election security legislation on July 24, just hours after Mueller’s testimony before the House Intelligence Committee. In coordinated statements, Warner, Blumenthal and Wyden took the floor to seek the Senate’s unanimous consent to take up and pass their three proposals: the FIRE Act, the Duty to Report Act, and the Senate Cybersecurity Protection Act. Each made reference to Mueller’s testimony and prior statements by other law enforcement and intelligence personnel on the need for cyber and election security reform. At the conclusion of each statement, however, Republican Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith objected to each motion, effectively defeating them. Senate Democrats chose not to pursue the issue.

On July 25, however, they tried again. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer was the first to take the floor. Referencing the prior day’s Mueller testimony as well as FBI Director Christopher Wray’s testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee earlier in the week, he implored Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to allow election security legislation to move forward. “There is no credence to the claim by the leader that we have already done enough in this chamber,” Schumer argued. “Mueller, Wray, [Director of National Intelligence Dan] Coats—all said we need to do more. All of them. Here in the Senate, the Senate Intelligence Committee led by Senator Burr of North Carolina, a Republican, has recommended we do more .... Yet leader McConnell and the Republican majority refuse to do anything.”

Schumer then described H.R. 2722, the SAFE Act, which he indicated he would ask unanimous consent for after remarks by Blumenthal. After summarizing the bill, Schumer said:

These are not revolutionary changes. They are basic, commonsense steps to greatly improve the security of our elections after President Putin conducted a systematic attack on our democracy and intends to do it again. The House has passed this bill already. We could deliver it to the president today. Now the Republican leader has already indicated his intention to bury this bill in the legislative graveyard. That is a disgrace. It is as if we said we don’t need a military, we don’t need ships off our shores, or planes in the air. Attacks on our elections are as great a threat to our national security as any other.

...

Where are our Republican colleagues? If we invite the Russians to interfere by not doing enough, and they do, and Americans lose faith in the fundamental wellspring of America, our grand democracy, this is the beginning of the end. Democracy in this country, as George Washington, James Madison, Benjamin Franklin warned us—we must do all we can to prevent foreign interference in our elections.

Schumer later moved for unanimous consent to consider the SAFE Act. But Senate Majority Leader McConnell objected, calling the bill “partisan legislation from the Democratic House of Representatives relating to American elections.” Referring to Democrats’ flagship House bill addressing a range of voting and election-related issues, H.R. 1, McConnell stated:

This is the same Democratic House that made its first big priority for this Congress a sweeping partisan effort to rewrite all kinds of the rules of American politics. Not to achieve greater fairness, but to give themselves a one-sized political benefit. The particular bill that the Democratic leader is asking to move by unanimous consent is so partisan, that it received one, just one, Republican vote over in the House. So clearly this request is not a serious effort to make a law. Clearly something so partisan that it only received one single solitary Republican vote in the House is not going to travel through the Senate by unanimous consent. It is very important that we maintain the integrity and security of our elections in our country. Any Washington involvement in that task needs to be undertaken with extreme care and on a thoroughly bipartisan basis. Obviously this legislation is not that. It’s just a highly partisan bill from the same folks who spent two years hyping up a conspiracy theory about President Trump and Russia and who continue to ignore this administration’s progress in correcting the Obama administration’s failures on this subject in the 2018 election. Therefore I object.

Blumenthal later returned to the floor to once again ask for unanimous consent to consider and pass the Duty to Report Act. But McConnell objected a second time, defeating the motion without further comment.

The merits of any specific proposal aside, the striking feature here is the Senate’s utter inability—even in the face of strong bipartisan agreement as to the nature of the vulnerability the country faces—to address it legislatively. There is plenty of blame to go around for this state of affairs, but a disproportionate share must fall on McConnell’s shoulders. As Senate majority leader, McConnell has almost single-handed control over what legislation comes to the Senate floor for debate. While the Democrats’ motions for unanimous consent were no doubt intended to have a political effect, dismissing the underlying legislation as partisan without discussing the substance does the country a disservice. Nor is McConnell’s argument that the Trump administration and Congress have already done enough on election security persuasive in the face of the conclusions reached by the Senate Intelligence Committee, various national security officials and policy experts, and even other Senate Republicans.

In a different era, the Senate Intelligence Committee’s findings would demand action from lawmakers. In this era, Mueller’s testimony and the report together provoke just another partisan skirmish.