Can the Federal Government Override State Government Rules on Social Distancing to Promote the Economy?

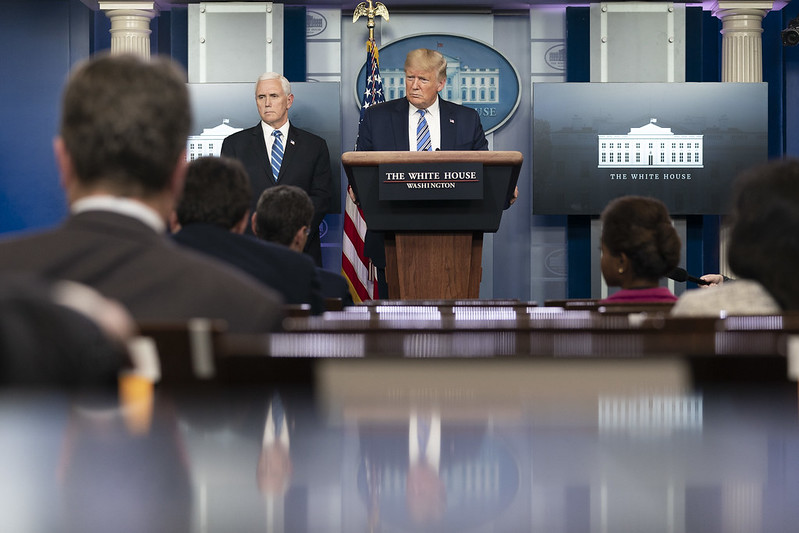

A wary president eyes the economic fallout from social-distancing measures that states have adopted in a bid to flatten the curve. If he wants to do more than just advocate against them, what then?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

A wary president is eyeing the economic fallout from movement restrictions intended to flatten the COVID-19 curve and is calling for a “return to business” sooner rather than later. But those restrictions flow primarily from rules promulgated by state governors, county commissioners and mayors—not from the federal government. Does the president have the power to force changes if state and local officials won’t follow his lead?

1. The practical power of Trump’s advocacy

The president, of course, is entitled to express his views on this point. This alone will likely have a significant practical effect in at least two senses.

First, when Donald Trump selects a narrative and begins to advance it, especially through his Twitter account, it has a remarkable effect on those who trust him. The more the president speaks against more robust forms of social distancing (such as shelter-in-place rules), the more noncompliance we are likely to see on the ground level from citizens sympathetic to the president (and let’s face it, there’s a limit to how much compulsory compliance state and local authorities can effectuate even absent the powerful headwinds that would follow from Trump’s opposition).

Second, that same effect will translate into mounting political pressure on GOP officeholders at the state and local levels who might otherwise support these measures. This pressure will be especially strong once Fox personalities and others get the bit in their teeth and start to amplify the message. To be fair, this would hardly be the first time that an administration has used rhetoric to pressure a state government official on a question concerning the best response to infectious disease (although in that prior example, Anthony Fauci’s scientific assessment supported rather than ran contrary to the White House preference).

At any rate, let’s assume now that some substantial number of state and local jurisdictions do not play ball with the Trump administration, that they hold to their shelter-in-place rules. What then? Can the president compel state and local cooperation with his preferred policy?

2. No, the president cannot simply order state and local officials to change their policies

Here we have issues that fall under the headings of both federalism and separation of powers. Let’s start with federalism.

Most readers will appreciate this already, but it needs to be said: Our constitutional order has a federal structure, meaning that (a) federal powers are supreme, yes, but limited in scope and (b) the state governments are independent entities, not mere subordinate layers under and within the federal government (that is, the federal-state relationship is not similar to the way that counties and cities are subordinate layers under the state governments).

What follows from this? The federal government cannot commandeer the machinery of the state governments (or, by extension, of local governments). That is, the federal government cannot coerce the states into taking actions to suit federal policy preference. See, e.g., New York v. United States and Printz v. United States. And so, the federal government cannot compel state and local officials to promulgate different rules on social distancing and the like.

3. But could the federal government override contrary state and local rules?

As noted above, federal law is supreme over state law in our system. And so, if there is an otherwise-constitutional federal law compelling an outcome that runs contrary to a state or local rule, the federal law prevails. But it does not follow that President Trump can therefore override state and local rules on matters like shelter-in-place.

First, no currently existing statute plausibly can be read to confer such an authority on the president. The Stafford Act, the Defense Production Act, the Public Health Service Act, and the various statutes triggered by a declaration under the National Emergencies Act—none of these come close to authorizing something like this.

Second, there is little chance that this Congress is going to pass a statute that even purports to confer authority on the president to override state and local rules. I just do not see the House cooperating in such an effort.

Third, the president cannot plausibly claim inherent Article II authority to accomplish an override. Recall that President Truman, in the midst of the Korean War and facing the prospect of a strike in the steel industry that might disrupt the flow of arms and ammunition, asserted emergency Article II authority in order to temporarily nationalize the steel industry. The Supreme Court famously struck down that action as an unconstitutional usurpation of the authority of Congress, notwithstanding the exigency, in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer.

4. Could someone sue to strike down the shelter-in-place orders on “dormant commerce clause” grounds, because they so plainly disrupt interstate commerce?

Not likely. The phrase “dormant commerce clause” refers to an unusual quirk in constitutional law doctrine: Whereas most of the enumerated powers of Congress listed in Article I, Section 8, function as just that—recognitions that Congress has power to legislate on a topic—the Interstate Commerce Clause in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3, has a dual function. Yes, it recognizes the power of Congress to legislate on that topic. But, as construed by the Supreme Court over time, it also has a legal consequence even where Congress has not made use of it. Even when “dormant,” it can be used in litigation as the basis for a court to strike down as unconstitutional a state action that unduly discriminates against out-of-state commerce or that unduly burdens interstate commerce.

Might that concept be useful here, if invoked by a plaintiff in one state suffering economically from the effects of a shelter-in-place order in another state?

Such a case might indeed be brought, but so long as the present circumstances hold it ought to fail on the merits. This is not a “discrimination” scenario in which one state is burdening out-of-state commerce, so we can set that prong of the analysis aside. The issue, instead, is whether this constitutes an “undue burden” scenario in which the state’s purposes are outweighed by the costs the state is imposing on interstate commerce.

This test requires, at bottom, a balancing of the competing interests. On the one hand, the shelter-in-place rules plainly have a tremendous debilitating impact on much interstate commerce. But on the other hand, the underlying justification here—using the police powers of individual states to address a public health emergency of the first order by employing measures reasonably designed to save a large number of lives—is a powerful one. At least so long as present circumstances persist, with lives at stake through the flatten-the-curve imperative, it is difficult to imagine a court tipping the balance in favor of striking down such measures.

5. Can the president instead achieve his goal by leveraging control over discretionary forms of financial and other aid?

On the one hand, it is clear from cases like South Dakota v. Dole and N.F.I.B. v. Sebelius that when Congress places conditions on state receipt of federal funds, those conditions are unconstitutional if they are sufficiently compelling to be deemed coercive. In such instances, the federal condition is tantamount to forbidden commandeering. Just where that line lies, of course, is not at all clear. But that’s not really our current situation, is it? There is no federal spending provision that came with strings attached in the form of conditions requiring states to move away from shelter-in-place in order to receive the funding, nor is there likely to be one.

Instead, we are contemplating a situation in which the president, or officials at lower levels, might be in position as a practical matter to withhold, modulate or delay various forms of discretionary aid (federal funds, for example, but perhaps other things—including things not directly related to the current crisis), while either expressly or (more likely) implicitly signaling that the state must comply with the president’s policy preferences on the COVID-19 response. Put another way, we are contemplating a situation in which the administration might subtly (or not so subtly) graft a condition onto existing aid mechanisms. To borrow a phrase, it would be a quid pro quo.

In my view, this would be as much a violation of the anti-commandeering principle as the direct-coercion scenarios noted above, and arguably even worse given the lack of public transparency. But it also might be difficult to detect, or at least to prove, that the administration is imposing such a condition. In any event, the long timeline associated with having to litigate such a matter renders the point practically moot. Should the president take this route, the most one can hope for might simply be reliable reporting exposing the coercion and resulting pushback from the public and other government officials.