China Blocks Clubhouse

Lawfare’s biweekly roundup of U.S.-China technology policy and national security news.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On Feb. 8, Chinese censors removed Clubhouse, the audio-sharing social app, from its Apple app store and attempted to rid the Chinese internet of references to the app, clamping down on what had been an unusual break in the Great Firewall.

Prior to the ban, ordinary Chinese citizens had been able to share audio on Clubhouse with individuals outside the mainland about sensitive political topics, from repression in Xinjiang to Li Wenliang, a doctor in Wuhan who sounded an early alarm on the coronavirus pandemic and was punished by regulators.

Clubhouse’s rise and fall took just a week: A Jan. 30 appearance by Elon Musk on the platform piqued users’ interest. By the weekend of Feb. 5, Chinese engagement with the platform was spiking. Many thousands of users from the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan flooded Clubhouse, filling multiple chatrooms capped at 5,000 participants. Some users from the mainland said they learned pieces of their history and stories of their present that they had never previously encountered; one visitor felt she was “binging free expression.” By Monday, the app was banned.

Clubhouse was not perfect from an equity perspective: Its $47 invitation fee, requirement of a virtual private network (VPN), and exclusivity to iOS devices prohibited many would-be Chinese users from participating. And there are serious concerns that Clubhouse is unable or unwilling to fully protect the identities and data of its users, leaving many Chinese citizens who spoke out in the discussions frightened of retaliation.

But it gave Chinese citizens a fleeting glimpse of free speech online—a right greatly curtailed on China’s mainstream internet—and a chance to communicate across national and cultural lines.

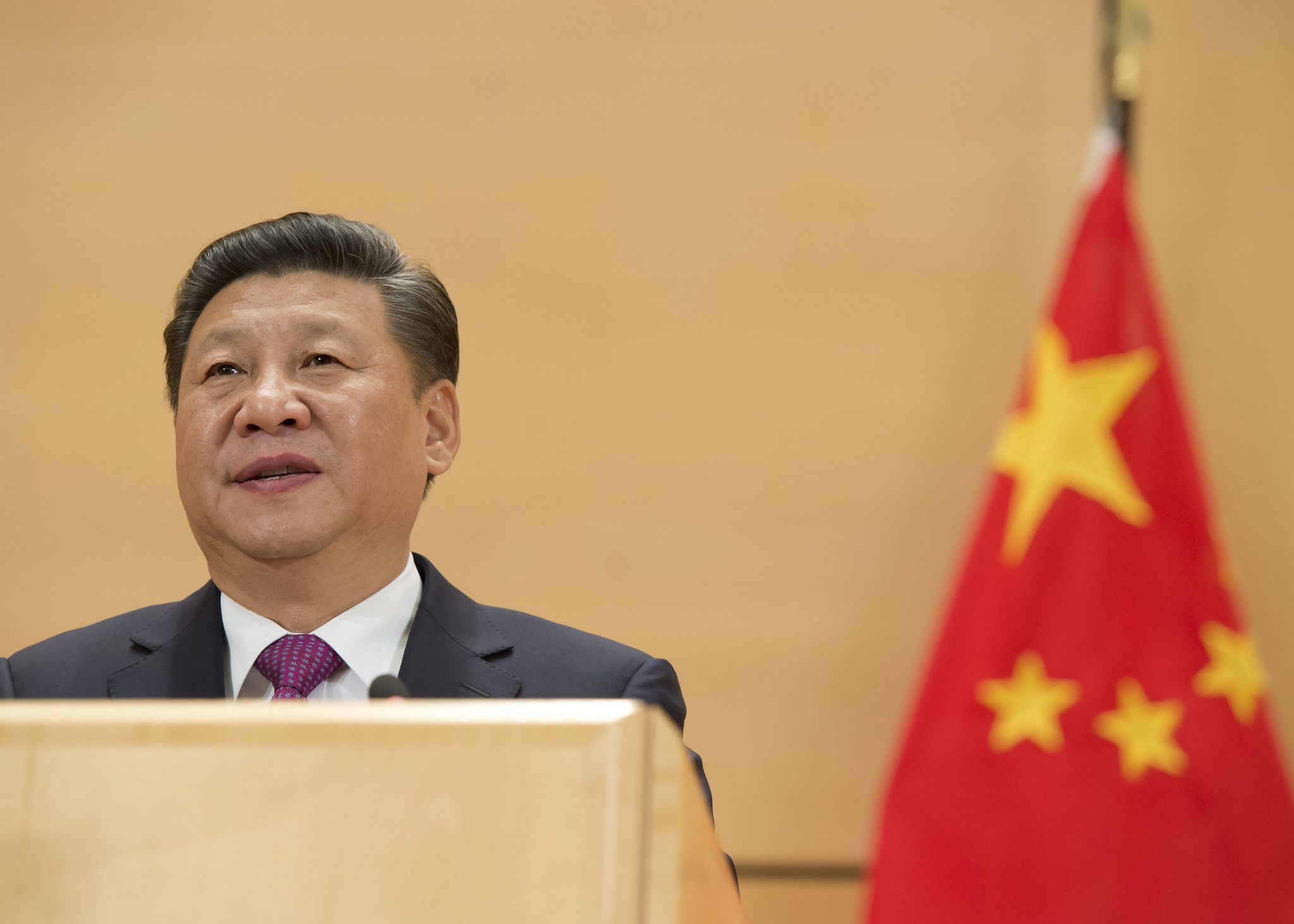

President Biden and President Xi Have Their First Call

President Biden spoke with Chinese President Xi Jinping for two hours on Feb. 11, the first call between the two leaders since Biden took office. The Chinese Communist Party-backed Global Times celebrated the duration of the call as a “very positive message[,]” which showed “in-depth communication” between the two leaders. Xinhua published a lengthy readout of the call emphasizing Xi’s message to Biden. Both leaders indicated their willingness to work together on issues of mutual concern, including climate change and fighting the coronavirus.

The White House summary of the call differed considerably in tone from China’s readout. According to the White House, President Biden “underscored his fundamental concerns about Beijing’s coercive and unfair economic practices, crackdown in Hong Kong, human rights abuses in Xinjiang, and increasingly assertive actions in the region, including toward Taiwan.” According to Xinhua, President Xi stressed that situations in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Xinjiang “are China’s internal affairs and concern China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and the U.S. side should respect China’s core interests and act prudently.”

Commentators are concerned that “narrowing differences” on those core issues “is going to be very challenging” but optimistically observed that Xi did not set preconditions for cooperation in areas of mutual interest.

In 2011 and 2012, while Xi was vice president of China and Biden was vice president of the United States, the two men spent more than 24 hours in private meetings and traveled 17,000 miles together. In a recent interview, President Biden said that he believed he has spent more time with Xi than any other world leader and knows the Chinese president “pretty well.”

Chinese Government Promulgates New Antitrust Rules

On Feb. 7, China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) published new antitrust rules affecting major firms in tech and e-commerce. The rules, first announced in November, take aim at monopolistic practices by platforms such as Alibaba and JD.com, as well as financial technology companies like Tencent and Ant Group. In a question-and-answer session after the announcement, SAMR stated that the firms’ “use of data, algorithms, platform rules and so on make it more difficult to discover and determine what are monopoly agreements.”

Compliance with the regulations will require companies to provide regulators with significant visibility into companies’ proprietary information, including algorithms to gather consumer data and set prices. While the regulations do not include specifics on enforcement, it is possible that the government will put the onus on the companies to prove that their algorithms and market practices are fair. That strategy was recommended in a Jan. 7 report published by a consumer group connected to the Chinese government, on the improvement of tech firms’ transparency and consumer protection.

Private companies are also battling each other over alleged monopolistic practices: ByteDance is suing Tencent for abusing its market dominance. Tencent promised retaliation, alleging that its competitor had misused consumer data.

Chinese tech stocks were mostly unhurt immediately following the antitrust rules’ promulgation, possibly because the cost of the regulations had been priced in during the shock of the initial announcement in November. The head of China’s antitrust regulator stated in an interview that the new rules would facilitate domestic consumption, a central focus of President Xi’s effort to ensure continued Chinese economic growth.

Huawei Sues FCC for Removal From “National Security Threat” List

On Feb. 8, Huawei filed a complaint in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, asking for judicial review of a Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ruling that the company poses a national security threat. In June 2020, the FCC ruled that Huawei and ZTE, another Chinese technology company, pose a national security threat given the “overwhelming weight of evidence” of those two companies’ “close ties to the Chinese Communisty Party and China’s military apparatus.” As a result of the ruling, money from the FCC’s Universal Service Fund (USF) may no longer be used to purchase, maintain, or otherwise support equipment or services from those companies.

The $8.3 billion-a-year USF subsidizes internet service providers deploying broadband in rural or underserved regions of the United States. Prior to the ban, many small or rural internet providers receiving USF money relied on Huawei equipment due to its relatively low cost.

In December 2020, the FCC reaffirmed its stance that Huawei represents a national security threat and voted unanimously to adopt new rules implementing the bipartisan Secure and Trusted Communications Networks Act of 2019. These rules went beyond a purchasing ban on Huawei equipment, issuing a “rip-and-replace” order requiring carriers to remove any equipment deemed a security threat and replace it with trusted equipment. The rip-and-replace order is estimated to cost small and rural carriers at least $1.6 billion, for which Congress has yet to allocate funds.

The FCC designation of Huawei and ZTE as threats to national security hinged on provisions of Chinese law, particularly the National Intelligence Law, which, according to the FCC, “obligat[es] them to cooperate with the country’s intelligence services.” Huawei denies this argument, claiming that the FCC’s threat designation was “arbitrary, capricious, and an abuse of discretion.” Such a finding would require federal courts to set aside the designation, but the FCC continues to defend its decision as based on “a substantial body of evidence.” Experts disagree on the extent and significance of cooperation between Chinese technology companies and China’s government and military.

In a written response to questions from Senate Republicans on Feb. 3, President Biden’s nominee for secretary of commerce, Gina Raimondo, stated that she “had no reason to believe” Huawei should be removed from the list of banned entities.

Other News

Biden Asks for Pause in WeChat, TikTok Proceedings

On Feb. 10 and 11, the Biden administration asked two federal courts to pause proceedings in the cases surrounding the Trump administration’s attempted bans of WeChat and TikTok.

The Justice Department’s filings to the U.S. Courts of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and the D.C. Circuit stated that the Department of Commerce would review the agency’s actions, in part to reexamine the purported national security threat posed by the apps. The Department of Justice used similar language in both documents. According to the filing in the D.C. Circuit, the Commerce Department’s reassessment is expected to either “narrow the issues presented or eliminate the need for this Court’s review entirely.”

Negotiations for Oracle and Walmart to buy the U.S. arm of TikTok have also been paused. U.S. national security officials are reportedly in talks with ByteDance representatives to assess what adjustments could be made to ensure individual data security for U.S. consumers while allowing TikTok to continue its operations in the United States.

Meanwhile, on Jan. 26, India made its ban on TikTok permanent.

Chinese Space Probe Tianwen-1 Reaches Mars Orbit

China’s Tianwen-1 spacecraft successfully reached Mars orbit on Feb. 10, seven months after launching from Wenchang in southern China. The spacecraft will orbit Mars once every 10 days, at times coming as close as 165 miles from the surface of the Red Planet. The orbiter will return high-resolution photographs of the Martian surface to Chinese scientists, allowing them to pinpoint potential landing sites for the rover carried onboard Tianwen-1. In May or June 2021, China will attempt to land the 500-pound rover on the surface of Mars.

Tianwen-1 is China’s first successful interplanetary mission. In Mandarin, the name “Tianwen” translates roughly to “questioning the heavens.” The United States and the United Arab Emirates also launched uncrewed missions to Mars in recent months, taking advantage of a narrow window of time when the Earth and Mars are closer than usual in their orbits, occurring once every two years. Both China and the U.S. are gathering data on the presence of below-ground water ice on Mars, as well as gaining a better understanding of the planet’s geology.

Deep space exploration remains a topic of international cooperation. On Feb. 10, Zhang Kejian, director of the China National Space Administration, stated, “Exploring the vast universe is the common dream of all mankind. We will cooperate sincerely and go hand in hand with countries all over the world to make mankind’s exploration of space go further.” Officials at NASA and the European Space Agency offered their congratulations to the Chinese team, with NASA’s top scientist saying, “There is much to discover about the mysteries of Mars and we look forward to your contributions!”

President Biden’s space advisers have argued that the United States should do more to cooperate with China on space exploration. Such efforts have been severely constrained following passage of the so-called “Wolf amendment” to the NASA authorization bill in 2011, which cites national security and human rights concerns as a basis for limiting the U.S. space program’s engagement with China.

In 2021, NASA will begin a series of missions known as Artemis, which will involve landing the first-ever woman on the Moon by 2024 in preparation for longer crewed missions to Mars.

5G Rollouts Continue

The United States and China are already competing for 6G supremacy. But the 5G rollouts in both countries are far from over.

Despite the huge number of 5G base stations constructed in China, actual use of 5G services remains low as a percentage of the population. Subscriber numbers are expected to rise quickly as prices drop.

The 5G rollout in the United States was underwhelming in 2020, though the Jan. 15 FCC auction of 5G spectrum in the United States shattered records. On Feb. 2, Boston Consulting Group reported that 5G is expected to add millions of jobs and trillions of dollars to the U.S. economy by 2030. The United States’s 5G device penetration rate is about the same as China’s, both at approximately 8 percent, but PricewaterhouseCoopers predicts that 5G use in America will not reach a critical mass until 2023.

Developments in both countries are being influenced by Qualcomm’s continued collaboration with Chinese firms China Mobile and ZTE, despite the U.S.-China tensions over tech. Frequent announcements from the firms’ joint projects indicate significant advances, including high-precision positioning technology, in the “Industrial Internet of Things.” A recent report suggests that 5G connected devices will expand most rapidly in energy management and government surveillance.

Tesla Pledges Compliance

On Feb. 8, China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) summoned Tesla executives to respond to customer complaints. Chinese buyers of Tesla’s Model 3 car, manufactured in Shanghai for the Chinese market, say they’ve experienced “abnormal acceleration” and battery fires. Tesla responded on Weibo, the Chinese social network comparable to Twitter, with an apology and a pledge to “accept the guidance” of Chinese regulators and investigate the apparent quality assurance issues.

Beijing has given Tesla unusual leeway since the company entered the Chinese market in 2013. China is the largest electric vehicle market in the world, and policymakers have been encouraging consumers to switch from gas-powered cars. In 2017, Tencent took a 5 percent stake in the American automaker. Tesla more than doubled its sales in China in 2020; the Chinese market now composes one-fifth of Tesla’s overall sales. And Elon Musk, Tesla’s founder, has garnered a cult following in the country.

But there is no guarantee of continued success. In China, the Model 3 is far more expensive than the domestic alternatives, and Chinese regulators may decide to prioritize domestic manufacturers, especially if Tesla’s quality issues—which have also plagued the company in the United States—continue. Tencent, one of China’s biggest tech firms, recently announced a partnership with Geely, China’s largest privately owned automaker, to jointly develop driverless and “smart car” technology.

Musk’s contrition in response to the Chinese regulators’ chastisement stands in contrast with his usual rebellious attitude toward U.S. lawmakers.

Commentary

Josh Freedman, a fellow at Harvard’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, writes for Foreign Affairs on why China is cracking down on its tech monopolies.

Protocol collects thoughts from experts on what the West can learn from Chinese tech firms. Answers include more public investment, more targeted antitrust regulation, and smarter hiring and training practices. In Wired, Luke Patey examines the lessons that President Biden can draw from China’s growth in technology.

Winston Ma, an adjunct professor at New York University, suggests on CNBC that China is using its relationship with the European Union to reduce its reliance on the United States.

Yun Jiang and Adam Ni write for China Neican on Taiwan, the realities underlying popular policymaker misconceptions about China’s “debt diplomacy” and its “vaccine diplomacy.”

Sean R. Roberts examines the roots of cultural genocide in Xinjiang in a piece for Foreign Affairs.

Jonathan E. Hillman puts forth an essay for the Center for Strategic and International Studies on how the United States can compete with China’s Digital Silk Road Initiative.

Jordan Schneider and David Talbot write for Lawfare on potential updates to the U.S. economic policy toolkit that would improve the United States’s China strategy.

Mia Shuang Li reports for Slate on the experience of Chinese Clubhouse users for the brief window of time before the Great Firewall prohibited access to the app.

.jpg?sfvrsn=e915b36f_5)