China’s Counterterrorism Ambitions in Africa

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: China is expanding its security role around the world, often in the name of counterterrorism. Jason Warner of the U.S. Army’s Foreign Military Studies Office details how China is expanding counterterrorism assistance in Africa and Beijing’s motivations. He argues that much of this activity should not be of concern to the United States, although it deserves regular scrutiny.

Daniel Byman

***

Africa is now the epicenter of global terrorism due to al-Qaeda and Islamic State militant violence. Over the past decade, African states have turned to the United States, more recently Russia, and once upon a time France for counterterrorism assistance. Historically, China has had a negligible role in counterterrorism in Africa; instead, its primary role on the continent has been as an economic partner. However, China has begun quietly making inroads to become a much more significant counterterrorism partner with African states, promising potential partners increased cooperation under the auspices of its Global Security Initiative (GSI).

China’s “New” Interest in African Counterterrorism

China’s contemporary and expanded push in African counterterrorism has come under the banner of the GSI, which it introduced in 2022 as a new, alternative framework to the current Western-led security order. In line with China’s broader national security ethos of combating the “three evils”—ethnic separatism, religious extremism, and violent terrorism—the GSI’s vision of global security emphasizes territorial sovereignty and non-interference, and it has a clear focus on counterterrorism. In its initial rollout, the GSI’s counterterrorism focus was especially evident for the regions of Southeast Asia and Central Asia, but the framework mentioned little about counterterrorism in Africa.

However, in a 2023 GSI concept paper, China pledged to “[s]upport the efforts of African countries … [to] fight terrorism … and to provide financial and technical support to Africa-led counter-terrorism operations.” This statement indicated special attention; though the paper covered global topics, Africa was the only region treated with a discussion of counterterrorism. This was followed by a March 2023 UN speech by Liu Yuxi, special representative of the Chinese government on African affairs at the United Nations, focused exclusively on the need for more global action to combat terrorism in Africa. In the speech, Liu argued that the antidote to the rise of terrorism was economic development, which China could offer via the Belt and Road Initiative.

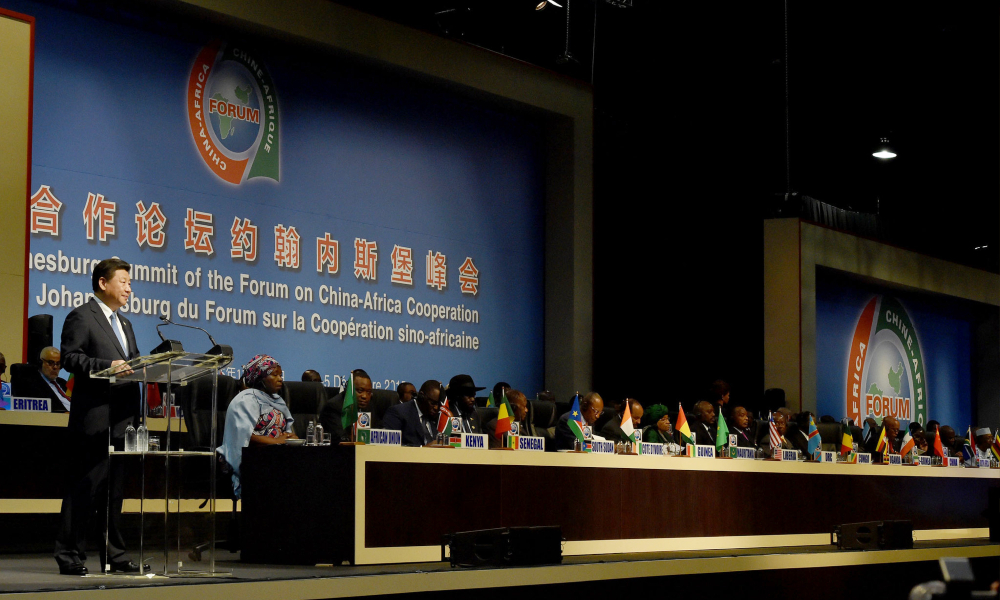

More recently, China’s push to move from being primarily an economic partner to a more security-focused partner was evident at the September 2024 Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), which U.S Institute of Peace China expert Carla Freeman argues “saw an unprecedented Chinese emphasis on its role in security on the continent.” In the opening speech of the summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping promised to provide Africa with approximately $140 million in grants for military assistance; training for 6,000 military personnel and 1,000 police and law enforcement officers; participation in joint military exercises, training, and patrols; and invitations for 500 young African military officers to visit China. In his remarks, though, Xi did not state an explicit interest in counterterrorism, suggesting that he did not want to frame the engagement through the lens of counterterrorism assistance because of the perceived inefficiencies of French, U.S., and Russian counterterrorism assistance that have made it a potentially polarizing issue in Africa.

Beijing’s interests also have been marked by other evident, though quiet, steps since the rollout of the GSI. These included China’s hosting of the first and second Horn of Africa Peace Conferences in 2022 and 2024 and a joint counterterrorism military exercise with Mozambique and Tanzania in August 2024. In line with its broader ethos, China’s increasing forays into African counterterrorism have been calculated, quiet, and generally risk averse.

China’s Developing Role

The genesis of Chinese defensive anti-terrorism measures (to be distinguished from offensive counterterrorism initiatives) in Africa was the protection of Chinese investments and citizens based on the continent. As its economic presence on the continent began to grow with the 2013 launch of the Belt and Road Initiative, China deployed “private” security contracting firms (with links to the Chinese state) to protect its investments. These included, for instance, teams safeguarding mining projects in unstable countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Sudan, and South Sudan. Beyond protecting enterprises, China has deployed private security firms to ensure the safety of increasingly vulnerable Chinese citizens working in such projects around the world—individuals who have been described as “sweet pastries” by would-be Nigerian kidnappers due to the expectation of lucrative ransoms. Indeed, Chinese nationals have been kidnapped by violent extremist organizations and criminals in both Nigeria and the DRC, and nine Chinese gold miners were killed in the Central African Republic in 2023.

While some of China’s efforts to combat terrorism in Africa have historically been via these “private” contractors, the state has been engaged as well. In around 2014, Chinese analysts began referring to “an arc of instability caused by terrorism” in Africa that included Mali, Nigeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Somalia. More tellingly, Chinese peacekeepers have been involved in African conflict zones afflicted by terrorism as UN peacekeepers, most notably in MINUSMA in Mali, which one think tank argued demonstrated “China’s willingness to further engage in [counterterrorism] operations.”

Today, perhaps the most significant, if underappreciated, conduit by which China is engaging in counterterrorism is via police and law enforcement training. Between 2018 and 2021 alone, some 2,000 African police received Chinese training from across 21 police academies associated with China’s Ministry of Public Security. Paul Nantulya of the African Center for Strategic Studies has underscored the analogous nature of African and Chinese police and their role in counterterrorism: China’s approach, which starts from the premise that the state possesses absolute power to impose security and can deploy a police force centralized under the executive, comports well with the modus operandi of many African police forces.

China has also found a niche in Africa helping states to surveil and suppress would-be restive citizen groups by exporting Smart City technology. While African civil society groups have worried about the ability of these technologies to help states crack down on political dissidents, some observers have suggested that the effectiveness of these efforts has been limited by the internet penetration and digital infrastructure in some African countries, as well as the technical know-how required.

An Inevitable Clash?

The good news is that the ways that China is seeking to insert itself into the African counterterrorism landscape, thus far, raise no major red flags. Geopolitically, Beijing vaunts greater global counterterrorism cooperation at the United Nations—leading the creation of the UN Peace and Development Trust Fund, which funds counterterrorism efforts—and argues for more resourcing and empowerment of African international organizations, including the African Union, and regional economic communities, including the Economic Community of West African States. These are hardly controversial initiatives. China’s strong view that poverty is a root cause of terrorism is also benign, as are its interests in the processes of terrorist radicalization and deradicalization. To date, China has displayed none of the recklessness that Russia has shown in the African counterterrorism space; indeed, Chinese law prohibits contractors from carrying weapons internationally. Its use of private military contractors, rather than overt deployments of the People’s Liberation Army, is evidence of Beijing’s demonstration of its adherence to its principle of “non-interference.”

Still, points of friction might emerge. The United States might not see itself in direct, physical competition with China in the African counterterrorism space but, instead, might perceive an ideological conflict in the form of clashing norms related to rule of law initiatives, security sector reforms, and judicial reforms. More acutely, if Beijing aids African states in silencing minorities in the way that China has done with its own Uyghur population, Washington will not stand by as a quiet onlooker. And, on a grander geopolitical scale, the GSI and the counterterrorism ambitions that China has embedded within it are inherently in opposition to the U.S.-led global security order. China’s absorption of African states into its security orbit through the conduit of counterterrorism cooperation will not be welcomed by the United States.

China’s efforts to gain influence via counterterrorism in Africa are clear, quiet, and pragmatic. While the red lights are not yet blinking in Washington regarding Beijing’s efforts, they certainly should not be overlooked.