China’s NFT Plans Are a Recipe for the Government’s Digital Control

China’s vision of the next iteration of the internet is one in which China controls and vets who can build on it.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

China is doubling down on the idea of a wholly digital economy, constructing software infrastructure to support more expansive data analysis that is likely to strengthen the Chinese Communist Party’s authoritarian control, as well as give China an international edge in technological innovation. The latest part of China’s digital economy strategy is flying under the radar, probably because it is based on a software innovation commonly thought of as nothing more than the most recent cryptocurrency fad: non-fungible tokens (NFTs). NFTs have sparked viral memes and tech startup innovation. China is in the midst of launching a state-backed NFT infrastructure network with implicit geopolitical aims: to manage and ultimately oversee the architecture underpinning a potential future internet. China’s vision of this next iteration of the internet is one in which China controls and vets who can build on it.

NFTs are central to the potential new iteration of the internet—what some in the tech space refer to as Web3—that China seeks to oversee. Web3 is loosely defined as a system where online applications run on decentralized software and where users control and share their data via blockchain technology platforms, allowing greater interoperability, efficiency and business innovation. Web3 is an aspirational concept, not a concrete blueprint, and it has become a buzzword pushed by blockchain enthusiasts amid billions in venture capital funding. NFTs are key to the idea of Web3 because they serve as verifiable digital ownership of unique assets. When someone purchases an NFT, they have computer code tying the NFT to their digital wallet. Essentially, an NFT is a digital receipt. The NFT ownership is recorded on a blockchain. Anyone can view the ownership history of the asset and the owner can transfer that ownership to another wallet holder, as the result of a payment or some other condition that can be programmed onto the blockchain. As economies get more digitized and move toward Web3, there will be greater need to build software applications around digital ownership. Chinese officials are not publicly using the term Web3, but the Blockchain-based Service Network (BSN)—a blockchain development project overseen by China’s State Information Center—is investing in the idea that the future internet will require decentralized apps, with NFTs as a cornerstone of this future.

China prohibits trading of NFTs that run on popular cryptocurrency-based blockchains like Ethereum. Enforcement often falls to Chinese tech companies. The popular Chinese mobile payment platform WeChat Pay, for example, recently suspended accounts that were purchasing such NFTs.

The BSN describes its foray into NFTs as an “NFT network with Chinese characteristics.” This means that the network operates under the Chinese government’s rules, which outlaw cryptocurrencies. Most cryptocurrencies transact via pseudonymous software wallets through blockchains that are “permissionless,” meaning anyone online can operate the computer nodes to run the blockchain. Such blockchains lack a central authority to vet blockchain node operators’ identities. The BSN formally brands its NFTs as Distributed Digital Certificates (DDCs) and has tried to distance itself from standard NFTs, posting a blog article in February arguing that regular NFTs will fail because their permissionless infrastructure makes them vulnerable to fraud, scams and money laundering. China’s DDC network is built on a decentralized ledger, but it is not permissionless. To be a software developer on the DDC network, one must register and even upload a copy of one’s business license to the BSN’s DDC website. DDCs, however, are still NFTs. They are just created on a Chinese government-supervised blockchain. (For the sake of minimizing acronyms, I’ll still use the term NFTs for the BSN’s DDCs.)

Rebranding is common in China’s engagement with blockchain tech. In late 2021, the BSN coined a new, rather oxymoronic term for its blockchain infrastructure. The BSN now describes itself as an “Open Permissioned Blockchain.” Anyone can build on it, as long as they are vetted by Chinese authorities. And the BSN has a version for Chinese users and a version for users outside the country. In China, you cannot pay for NFTs via cryptocurrency tokens. For users to purchase NFTs on the Chinese version of the BSN platform, they must pay in China’s fiat currency, the yuan. That means users must connect with a Chinese financial institution to transact.

The current hype around NFTs globally manifests mostly as digital art investment. But the bulk of NFTs minted in China probably will not revolve around digital art. The BSN is focused on building infrastructure for digital commodities rather than digital investments. The BSN’s executive director said in January 2022 that he anticipates the network will mint billions of NFTs annually, mostly for businesses to certify and manage user accounts. The BSN aims to be a one-stop-shop platform for the daily need to verify ownership in the digital economy, a situation that it foresees as a 5- to 10-year journey.

In a recent interview, the BSN executive director offered an example of a mundane NFT digital commodity use-case on the BSN—vehicle ownership:

Every country has a motor vehicle department, and all car data is centralized. Selling a car or updating a license requires a trip to the motor vehicle department, which is inconvenient and inefficient. The data transmission will be more efficient if all car data is turned into NFTs with different sets of data controlled by different private keys. To increase transparency, all data will be saved on blockchains.

Although this use-case may be mundane, it points to the potentially systemic relevance and vast data-collection potential of the BSN. If car ownership records of people in China are housed on a state-controlled blockchain platform, it gives that platform tremendous importance in daily life and gives the government huge influence in granting or prohibiting access to basic functions of personal mobility and transportation.

The car title use-case may well become a gateway for constructing a massive government-run platform for all types of information that can be digitally collected and transferred. Since the BSN’s aim is to prevent the siloing of information, it is likely that other data points will be integrated with car title information. In addition to attaching the car’s make, model, and vehicle information number to one’s personal identity, there will probably be an NFT for the license plate itself, possibly connected to records of speed limit and parking violations. Biometric data (like from facial recognition software), court records, and payment information (remember that NFTs on the BSN will be paid through identified payment accounts) are likely to eventually exist and interoperate on the BSN. While all this data is already collected by most governments around the world, it tends to be housed separately and not assembled into one singular digital platform. This siloing is largely due to the varied database systems deployed worldwide. They were not created to talk to each other. The BSN’s vision, taken to its logical conclusion, is to put all this data into a format where it can be transmitted seamlessly across government and business entities. Both the Chinese car dealer and Chinese law enforcement would access data moving on top of the BSN. This would not be just a database. This would be the database.

A government-controlled blockchain system to register all things owned within China would strengthen the Chinese Communist Party’s digital authoritarianism over its population. The BSN’s leadership claims that the information about NFT end-users will not be stored directly on the DDC’s underlying network and will be held only by the vetted businesses and individuals who create the NFTs. But this assurance is weak since NFT operators will still be under Chinese regulatory supervision and China has recently implemented various information technology laws that give the government easier access to private companies’ customer data. The BSN’s executive director said last year that if developers do something that Chinese regulators don’t want on the system, the BSN operators can “click a button and delete a whole chain.”

While Chinese government surveillance is a clear risk to individual users of BSN platforms, a more strategic risk to nation-states exists if China can implement its technological vision: a shift in global economic competitiveness.

In December 2021, China released its 14th Five-Year Plan for National Informatization, a road map laying out the government’s vision for advancing as the leading power in the global digital economy. The plan emphasizes China’s aim to achieve breakthroughs in three “cutting-edge technologies”: artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and blockchain technology. The plan also pushes for Chinese leadership in “digital trade,” calling for the nation to set up international trials for “smart customs, smart borders, knowledge sharing and interconnection.” The vision of “informatization” in foreign trade is to build new “smart” digital channels to facilitate cross-border commerce, with China being the lead architect of such channels. Verifying digital ownership would be key to digital trade systems. The BSN’s NFT architecture could become well suited for that role.

Notably, the term “smart” is infused more than 200 times in the five-year plan as a catch-all term for internet-based systems driven by data collection, integration and analysis. It talks of smart network infrastructure, smart cities, smart courts, smart investigations and even smart elder care. While the BSN is not named in the five-year plan, the BSN mission of developing a worldwide ecosystem to “facilitate a simultaneous broadcast approach to communication between multiple IT systems” fits squarely within the Chinese government’s broader digital economy goals. In September 2021, a senior official at China’s State Information Center, which oversees the internet, described the BSN as China’s “high speed rail system” for data and that it would enable “one system for cross-border connectivity” in international trade. China’s separate national digital currency project—the eCNY—also can be viewed as an effort to make “smart money.”

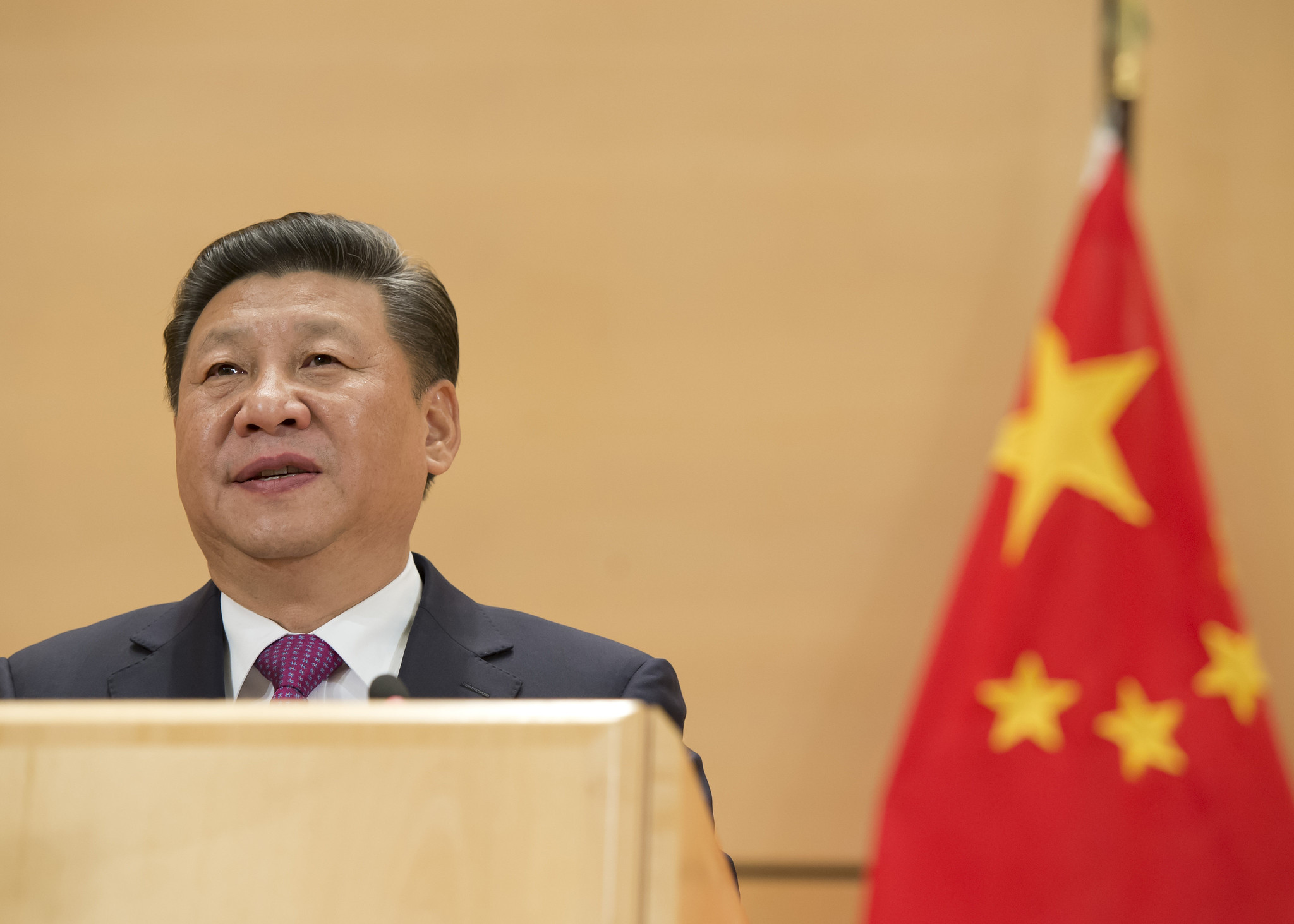

The push to informatize the Chinese economy aligns with President Xi Jinping’s remark in 2017 that “data is a new factor of production.” China’s strategy for economic advancement is all about harnessing data. The BSN is an effort to make data transmission more robust and dynamic in order to foster Chinese digital innovation. While it’s common to say that “data is the new oil,” for China, data is the new electricity—a factor of production for more than just industry and manufacturing. Data is the source to power everything running on software, which, increasingly, is just about everything in the economy.

China’s national strategy to double down on innovation around data systems is likely to play out in its great power competition, and its impact will probably unfold over more than a decade. The BSN, for example, is a generational project. The BSN architects see themselves as driving a process similar to the decades-long, research and development-intensive construction of the internet. Just as the U.S. gained immense strategic gains from the internet being developed largely by American computer scientists, the BSN aims to build the next-generation internet infrastructure that the rest of the world will have to build on in order to compete in the increasingly digital economy. This may seem like just a hopeful aspiration, but there are concrete developments to watch for as potential indicators of this aspiration becoming reality.

The expected rise of self-driving cars offers a good example of how BSN-led development could give Chinese industries a technological leg-up and make it difficult for the U.S. to compete in the global economy that relies on data collection and analysis. In mid-2021, the BSN executive director wrote an op-ed in which he again referred to vehicles to exemplify how the BSN’s platform could lead to greater digital innovation. He argued that if self-driving cars rely on today’s conventional information technology systems to share their speed and movement data with each other, the safety analysis process would be linear, slow and inefficient. Vehicles would ping nearby ones and could analyze only a few data points at a time. But by using blockchain technology to broadcast all vehicle data within a certain radius, cars could achieve “instantaneous synchronicity.” All driving data could be fed into a distributed database that allows for vehicles’ computers to read and assess the movements of perhaps hundreds of cars, whether or not they are in direct proximity. Instead of vehicles pinging just a few points of data, the distributed system would give vehicles full visibility into the data streaming around them. Collecting more data from more directions enables more analysis, and would enhance machine learning—all leading to better functioning vehicles.

The immediate benefits of this data innovation, if implemented on Chinese highways, would likely be safer roads and “smarter” transportation infrastructure. But the benefits would also reverberate to adjacent sectors, such as food delivery, police response, car insurance and geolocation software, among others. Many of these areas will likely involve some element of digital tickets, titles or receipts that could be represented through NFTs.

China would gain a big competitive advantage if such a system, built on government-owned BSN architecture, became the preferred building block for transportation applications infused into future self-driving car software. While other governments might urge their local industries to build their own blockchain-based infrastructure to support similarly dynamic data systems, such advances are not likely to come about without extensive research and development, pilots, and experimentation. While China’s vision of instantaneous synchronicity of data might be mostly theoretical at this point, the Chinese Communist Party is giving the strategic direction to map out these ideas to reality.

The BSN has greater international ramifications than other domestic blockchain efforts in China. Many private Chinese companies and government institutions are building and testing blockchain applications. But the BSN is oriented globally, intentionally designed to integrate with blockchains that originate outside China. The BSN development association is courting blockchain developers from around the world, pitching the BSN cloud infrastructure as cheaper to build on than competitor cloud server systems. The BSN even announced a partnership in March with a U.K. financial technology firm as part of an effort to bring BSN services to European developers. The BSN’s ultimate success depends as much on its uptake outside of China as it does on its domestic adoption. It should not be dismissed as just a small, local blockchain project.

China’s aspiration to lead the future digital economy should be met with three responses from the United States. The first response is a proactive domestic approach: The U.S. government should fund blockchain-based academic research in the U.S. just as it funded the early R&D in the 1960s and 1970s that led to the internet. While many in the U.S. crypto space analogize blockchain’s current development to the state of internet adoption in the mid-1990s, it is more like the state of the internet in the 1970s: lots of experiments, multiple protocols that have not been standardized, and, if you exclude cryptocurrency trading and price speculation, viable business use-cases are sparse, with minimal traction.

China is already taking a long-game approach by developing the BSN as foundational infrastructure for global commerce rather than seeking immediate commercial profit. This differs from U.S. blockchain development, in which many individual private-sector-led projects simply compete with one another, building their own blockchain systems that do not interoperate. The U.S. government could compete with China’s long-term strategy by funding, through the National Science Foundation, a decentralized internet sandbox for colleges and universities. This project should encourage computer science faculty and students in the U.S. to experiment with blockchain development, share best practices, build interoperability among different chains and eventually construct an open global standard for decentralized applications. Like the first iteration of the internet, this should bring about an open system with architecture that is not owned by one nation or entity. This is what Web3 could be, but not any version built on Chinese government infrastructure.

Second, the U.S. government, U.S. businesses, and the general public need to collaborate to articulate a vision of the perimeters of privacy in a growing digital economy. Policy discussion of data privacy typically focuses on for-profit corporations, which collect vast amounts of information from consumers’ online activities. But as the U.S. explores the possibility of creating a central bank digital currency (CBDC), new opportunities for collecting and analyzing financial data will arise, by both private and government entities. This discussion may initially center on standards for privacy in a U.S. CBDC, like the principles that the nongovernmental organization the Digital Dollar Project proposed in late 2021 and the privacy-maximizing digital currency framework known as Project Hamilton that MIT’s Digital Currency Initiative is working on with the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Third, every chance they get, U.S. policymakers should publicly raise alarms about the dangers of authoritarianism arising from the Chinese model of a government-controlled informatized economy. The digital currency and blockchain architects in China, whether in the People’s Bank of China, or private techs, will dismiss or downplay these risks, especially as they seek to entice foreign entities to collaborate with their financial technology pilots. But the U.S. message should be clear: Products that enable any government to have 360-degree awareness of all digital ownership and activity in real time also offer the technological foundations for overreach, abuse and tyranny.