China’s Successful Foray Into Asymmetric Lawfare

The Chinese government’s use of its own weak legal system to carry out “hostage diplomacy" may herald a new “asymmetric lawfare” strategy to counter the U.S.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The nearly three-year U.S. effort to extradite Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou from Canada on bank fraud charges ended suddenly on Sept. 24 when the U.S. dropped its extradition request, allowing Meng to return to China. At almost the exact same time, China released two Canadian citizens it had detained shortly after Meng’s 2018 detention, both of whom had been charged with endangering China’s national security. Although Canadians are relieved that their countrymen have returned home, the Chinese government’s use of its own weak legal system to carry out “hostage diplomacy,” combined with Meng’s exploitation of the procedural protections of the strong and independent Canadian and U.S. legal systems, may herald a new “asymmetric lawfare” strategy to counter the U.S. This strategy may prove an effective counter to the U.S. government’s efforts to use its own legal system to enforce economic sanctions, root out Chinese espionage, indict Chinese hackers, or otherwise counter the more assertive and threatening Chinese government.

As I explained to Lawfare readers shortly after Meng was detained in December 2018, seeking the extradition of a foreign national like Meng on bank fraud charges should have been a relatively routine and uncontroversial matter. Canada has an obligation to detain and turn over individuals sought by the U.S., as long as the U.S. charges satisfy the requirements of the U.S.-Canada extradition treaty. Canada, like many other U.S. extradition treaty partners, routinely detains and turns over such individuals to the U.S., no matter what their nationality (and the U.S. frequently reciprocates). The only question for Canadian courts was whether the charge satisfied the treaty obligations and if there was sufficient probable cause to arrest Meng. Under that legal standard, Meng should have been turned over to U.S. custody with minimal review because she would get full due process in any trial she received in the U.S. That is the whole point of having an extradition treaty, and Canada and the U.S. have frequently turned over individuals under this treaty, including Chinese nationals, with relatively little friction.

The Meng case went in a completely different direction in a way that illustrates China’s effective use of asymmetric lawfare. First, Meng took full advantage of her legal rights under Canadian law to challenge her detention and extradition to the fullest extent. She hired excellent and well-regarded legal counsel in Canada and the U.S. (who even retained frequent Lawfare contributor and former U.S. State Department Legal Adviser John Bellinger as an expert witness) to pull out all the legal stops possible. Her legal team launched a full-scale offensive against the circumstances of her detention, the legality of her extradition and the strength of the evidence against her. Although Meng’s legal team did not prevail in any of its clever and creative arguments, a fair consideration of their legal merits required time and consideration. Put another way, Meng’s legal team took advantage of Canada’s commitment to due process (a commitment not noticeably shared by most Chinese courts) to force lots of hearings and briefings on their challenges. This dragged out the extradition proceedings for almost three years. The judge considering Meng’s extradition was due to issue her final decision in October, but even if she ruled against Meng, Meng’s right to appeal that decision could have lasted another several years.

Meng’s ability to use Canada’s legal system to stretch out her extradition legal fight might not have mattered if the Chinese government had not also intervened. Just days after Meng’s detention in Vancouver, the Chinese government arrested two Canadian nationals living in China: Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor. Each was detained separately under murky circumstances, and the Chinese authorities did not formally charge either man until June 2020, nearly 18 months after their detentions. Even then, the charges merely accused both men of “spying on national secrets” and providing intelligence to “outside entities” without providing any evidence or even a description of the evidence detailing their supposed crimes. Both were kept in difficult, isolated conditions with such minimal access to the outside world that one of the detainees, Michael Kovrig, reportedly learned of the coronavirus pandemic only in October 2020 from a rare communication permitted with Canadian diplomats. Both detainees were tried in March 2021 in closed trials to which outside observers, even Canadian diplomats, were barred. It is no exaggeration to call the Kovrig-Spavor detentions textbook examples of “arbitrary detentions” under international law.

China’s ability to put this kind of pressure on Canada was made possible by its ability to intervene and control its domestic legal system without fear of any serious domestic impediments. Thus, the two Canadian detainees were held for months without any formal charges. The specific charges against them were not made public, nor even necessarily disclosed to the defendants, until their trials in March 2021. The timing of those trials was conveniently around the time the Canadian court in Meng’s case was considering one of her key arguments for dismissing her extradition proceedings. Put another way, there was no chance that the two “Michaels,” nor the Canadian government, could use the Chinese legal system to their advantage in the way that Meng used the Canadian legal system. Instead, the Chinese legal system served as a tool for the Chinese government to place calibrated pressure on Canada throughout the Meng proceedings while allowing the Chinese government to declare criticism of its judicial system interference in its “judicial sovereignty.”

The impact of China’s hostage-taking via lawfare was hard to discern at first. While Canada’s government denounced the detentions as “arbitrary,” most of the focus remained on the Meng proceedings. But as the Meng extradition proceedings began to drag out (due to the valiant efforts of Meng’s all-star legal team), the pressure on Canada’s leaders to free the two Michaels began to build. Leading foreign policy figures within Canada publicly called on the Canadian government to exercise its executive discretion to release Meng and reject the U.S. extradition request. Some Chinese Canadian groups held public demonstrations calling for her release, and 100 former Canadian diplomats sent an open letter demanding her release. Meanwhile, pleas from the friends and family of the two Michaels increased pressure on the government to find a way to win their release.

In other words, while China’s government faced criticism abroad for its detentions of the two Michaels, its hostage-taking worked. Canada’s government began a full diplomatic push to pressure or at least persuade the U.S. government to act and resolve the case as quickly as possible. In one report, Canada’s ambassador to China returned from Beijing and spent several weeks in Washington, D.C., apparently lobbying for U.S. government action to resolve the case through some kind of settlement. For understandable and laudable reasons, Canada’s government effectively became Meng’s advocate.

To be sure, recent reporting suggests the U.S. Department of Justice simply ignored this pressure from Canada, and made the offer to Meng for its own, completely independent reasons. This is possible in the sense that there was no formal instruction from the White House to make a deal with Meng. But the Chinese pressure campaign, with Canada as its unwilling proxy, almost certainly had an impact on the U.S. Department of Justice’s decision-making. The Justice Department has cited the lengthy delays it faced on appeals in Canadian courts, but those delays might have been surmountable if not for the reality that two Canadian hostages were left to suffer in order to allow Meng to exercise her full rights by exhausting her appeals. In an ordinary legal system, Kovrig and Spavor might have hoped to make their own legal challenges and make their own appeals. But China’s politically controlled legal system foreclosed that possibility.

Moreover, the terms of the Justice Department deal struck with Meng are somewhat odd. First, instead of requiring Meng to plead guilty, the department entered into a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA). A DPA means that the U.S. government pledges to delay any prosecution of the alleged crime for a specified period. In return, the defendant usually admits to wrongdoing, agrees to cooperate in the ongoing investigation, takes steps to prevent future occurrences and pays fines. What is striking about Meng’s DPA is that while she admitted to the “accuracy” of a statement of facts listing her fraudulent acts, she did not agree to either cooperate in the department’s ongoing prosecution of her company, Huawei, or pay any fines for the fraud that she admitted to committing. DPAs typically involve at least one of these two items. While Meng’s admissions can be used in the larger prosecution of Huawei as a type of cooperation, Meng’s role as CFO could have allowed her to provide much greater cooperation on the broader Justice Department case against Huawei. Meng also has no incentive to cooperate further because unlike most parties to a DPA, she no longer needs to fear U.S. prosecution as long as she stays in China.

Even if Canada’s pressure on the U.S. was not decisive, the Chinese government and state media have hailed Meng’s release as a huge victory for China, rather than just a personal victory for Meng. Chinese state media noted that China’s national power enabled Meng and Huawei to avoid the fate of other foreign companies, like France’s Alstrom, which had been subjected to severe fines in U.S. courts for foreign corruption. Put another way, even if China’s hostage-taking did not affect the outcome, China’s leadership almost certainly believes it did. Which means it is likely to try the same tactic again in the future.

This asymmetric lawfare allows China to use its weak and politically controlled legal system to stymie and even undermine the normal operation of the stronger and usually more effective legal systems in Canada and the U.S. Combining the dirty tactics of hostage-taking under the cover of its own legal system while taking advantage of the delays necessary to guarantee due process and procedural fairness in places like Canada resulted in a better outcome than China or Meng had any right to expect.

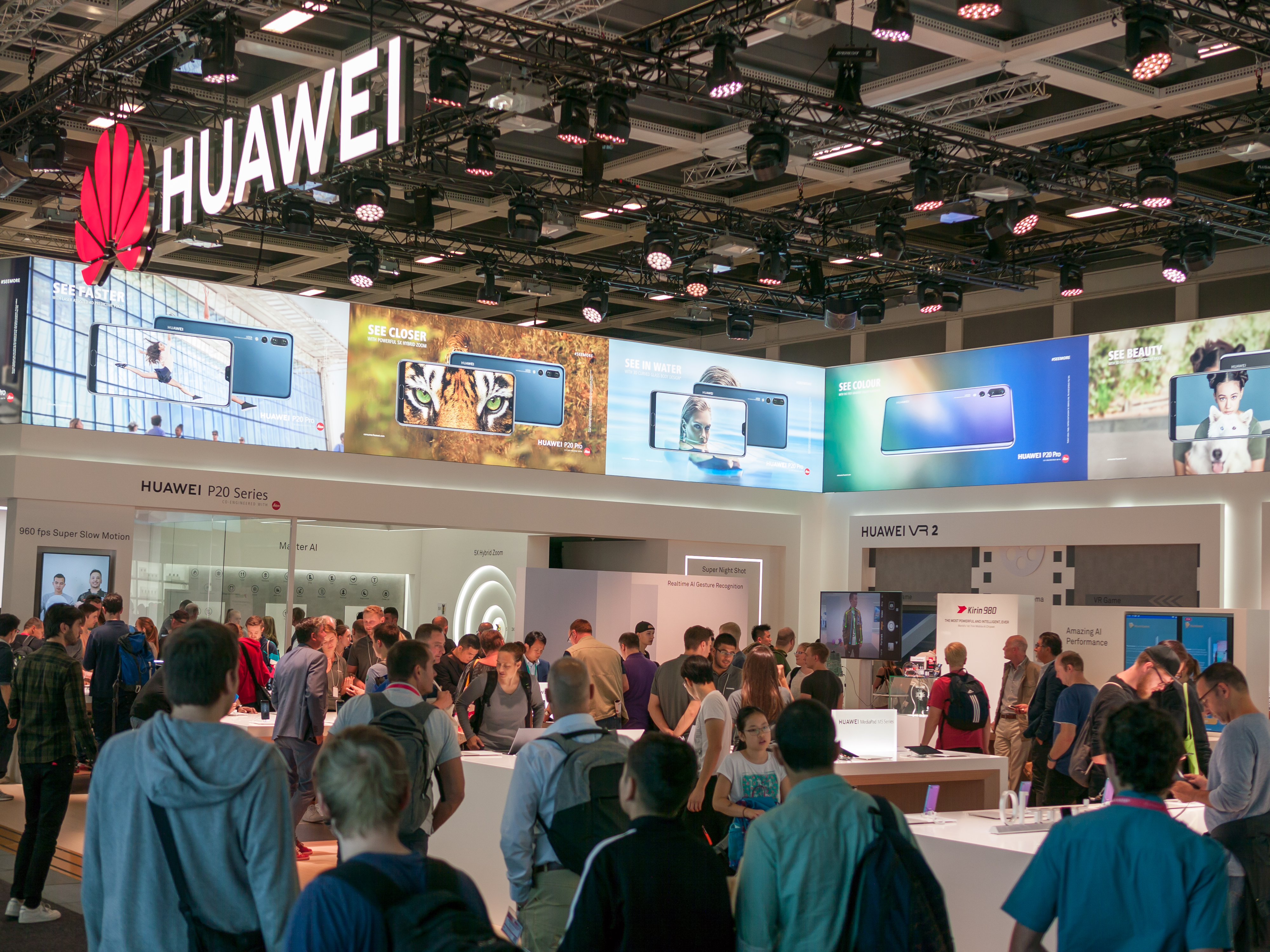

There are other possible forms of this asymmetry when Chinese companies like Huawei use Chinese law to shield their ownership structure from public scrutiny while purchasing foreign companies (and their technology) as they have the right to do under foreign laws. Huawei has also hired top legal counsel to fiercely contest its own prosecution in U.S. courts and even to bring a long-shot but creative constitutional challenge. Or even how Chinese companies have begun to use anti-suit injunctions in friendly Chinese courts to block any contestation of intellectual property rights in courts outside of China. In these small but important ways, China’s uneven and often appalling legal system is an asset to China and its companies. At the same time, China and Chinese companies are able to exercise their rights in strong and independent foreign legal systems to stymie or at least delay efforts to regulate or prosecute their wrongdoing.

There are no good or easy solutions to these tactics, since almost all of them would involve undermining the characteristics of the domestic legal systems that the American public values (such as neutrality, equal treatment of foreign nationals and companies, and comity toward foreign courts). And the success of China’s asymmetric lawfare in the Meng case does not mean it will always work in the future. But we cannot ignore the fact that China’s asymmetric lawfare seemed to work here (and China’s government almost certainly believes it did work), and it could be a powerful tool for China to use against the U.S. and similar countries long after the public has forgotten about Meng Wanzhou