The Complexities of Calling a Coup a Coup

Why is the U.S. government, and the Department of State in particular, slow to call a coup a coup?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On Feb. 1, the civilian government of Guinea-Bissau was threatened by an attempted coup. While the attempt failed, it came on the heels of a string of successful coups in West Africa, including one four weeks ago in Burkina Faso. As the Biden administration responds to these events, Congress and the public might be wondering: Why is the U.S. government, and the Department of State in particular, slow to call a coup a coup?

Many may also be concerned that this lack of decisiveness reflects the Biden administration’s hesitation to contend with these undemocratic developments and undermines its credibility to speak about the challenges facing democracy around the world, a stated priority for this administration. While State Department officials certainly have policy reasons for being cautious about using the term publicly, their sensitivity to use “coup” explicitly is primarily legalistic, rooted in a U.S. domestic law generally known as the “coup restriction.”

Understanding the Coup Restriction

The coup restriction limits the ability of the United States to provide certain kinds of assistance to a country following a determination that a coup d’etat has taken place.

The first iteration of the coup restriction was passed in 1984, in Section 537 of the Foreign Assistance and Related Programs Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 1985. Section 537 was aimed specifically at a potential coup in El Salvador. With the Cold War as a backdrop, El Salvador suffered a coup in 1979 and a civil war ensued. At the time of the law’s passage in 1984, the executive branch and Congress were entangled in a struggle over what assistance should go to the country. Section 537 restricted appropriations to El Salvador if the president of El Salvador should be deposed by military coup or decree. Congress passed a more expansive law in December 1985 that applied the coup restriction to all countries receiving direct assistance under the appropriations act and has since included a similar provision in the State Department’s annual appropriations act.

The most recent version of the coup restriction is Section 7008 of the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2021. The statutory restriction is triggered in situations in which the “duly elected head of government is deposed by military coup d'état or decree” or a coup d'état or decree in which the military played a decisive role in the ousting of a duly elected head of government. When there is news of a coup in a country receiving U.S. assistance, State Department officials must analyze the available facts and assess whether the facts and circumstances demonstrate that a duly elected government has been deposed, with guidance from the Office of the Legal Adviser on the effects of Section 7008 on the foreign assistance programming in that country.

If the State Department determines Section 7008 applies, the law restricts certain foreign assistance to the partner government, specifically the funds made available in Titles III-VI of the appropriations act. These titles cover bilateral economic assistance, international security assistance, multilateral assistance, and export and investment assistance.

Some restrictions on assistance in U.S. law have a “waiver” provision to provide maximal flexibility to policymakers, but Section 7008 does not contain such a waiver. In the event of a coup determination, there is only one way to lift the restriction, and it’s largely dependent on the restricted country: the secretary of state must certify and report to the appropriate congressional committees that the country in question has a democratically elected government that has taken office (not running for election or waiting to be sworn in). This certification is typically published in the Federal Register (for example, the certification on Thailand can be found here).

Congress ensured some flexibility in the law with respect to certain activities and funds. Section 7008 explicitly makes the restriction inapplicable to “assistance to promote democratic elections or public participation in democratic processes.”

In addition, certain authorities allow the department to obligate funding “notwithstanding” any other provision of law, which enables the relevant programming to avoid the otherwise applicable restrictions. For example, there are such authorities related to humanitarian assistance; assistance to specific countries seen as important strategic partners (Egypt and Pakistan, countries that faced coups while receiving U.S. economic and military assistance); assistance for democracy promotion, antiterrorism, and international narcotics control; and anticrime programming. Notwithstanding authorities are commonly included in the State Department’s annual appropriations act and attached to specific funds or programs. There is however, generally speaking, no “notwithstanding” authority that is available for military assistance, which is consistent with the purpose of Section 7008.

Implications for the Department of Defense

The Department of Defense has its own, separate appropriations to spend under the defense authorization acts and Title 10 of the U.S. Code. Section 7008 does not directly apply to Defense Department appropriations, but some of its authorities—most significantly the security cooperation authorities of Sections 331 and 333 of Chapter 16 of Title 10, which govern support for conduct of operations and building partner capacity—are subject to restrictive language that kicks in when Section 7008 has been triggered. Thus, if the State Department determines Section 7008 restricts assistance in country X, then the Pentagon can’t provide assistance in country X under Sections 331 and 333. As a practical matter, this is easy for the State Department to raise with the Defense Department because both of these authorities require concurrence of the secretary of state before they are applied.

Nonetheless, since the Defense Department does not have a Section 7008-equivalent limitation, Congress has created a gap in the law that could theoretically provide a legal basis for the continuation of some security cooperation despite the occurrence of a coup. But this is unlikely to happen for two reasons. First, for at least some Defense Department security cooperation authorities, there is the potential threat of non-concurrence from the secretary of state (such as Section 341). Second, politically loaded policy questions about whether to provide U.S. assistance in a country post-coup would be approached carefully by administration leadership to reach consensus—generally leaders aim to have a coherent foreign policy stance on any one country.

When Is a Coup Not a Coup?

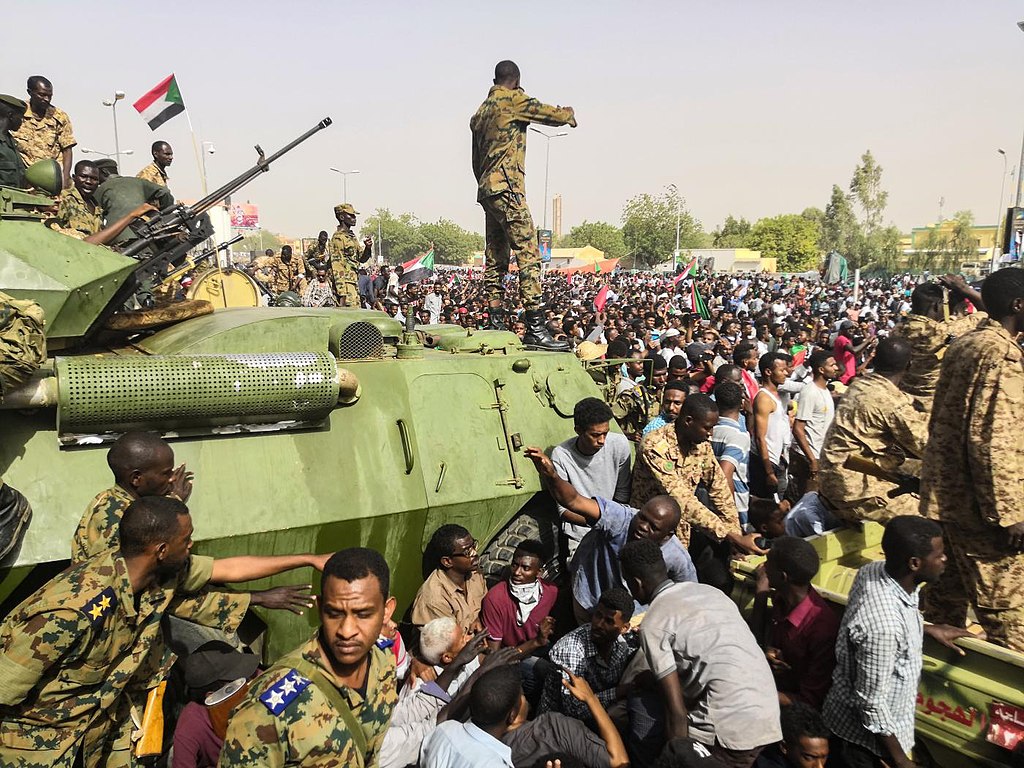

Not all coups, in the common understanding of the term, will necessarily meet the statutory standard under Section 7008. Recent developments in Sudan are a good example. In October 2021, the transitional civilian government was deposed by the Sudanese military in what was widely described as a coup, including by my organization, International Crisis Group. But the State Department still has not called it that, preferring to use language like “military takeover.”

As I recently suggested on Twitter, it is likely that the State Department assessed the civilian leadership in place was not “duly elected” for purposes of Section 7008 and that the events of October 2021 thus did not trigger the restrictions under 7008. In the case of Sudan, however, this is effectively a moot point as Section 7008 restrictions have applied there since 1989, when Omar al-Bashir led a military coup that overthrew the country’s democratically elected government. The restrictions under the law were never rescinded because a democratically elected government never took office after 1989.

In fact, in an exchange with reporters on Oct. 25, 2021, State Department spokesperson Ned Price was asked directly about whether the department had made a coup determination for Sudan. Price pointed out that the deposed Sudanese government had not been elected and reminded journalists that Section 7008 restrictions already applied. While Price said a coup determination makes no practical difference as it relates to assistance, he still resisted calling developments in Sudan a coup, even as a factual matter.

As was made clear from the October 2021 press briefing, the State Department’s careful parsing can trigger some confusion about how the U.S. government views or understands certain events. The department has been equally cautious in its initial press statements on Mali (referencing application of Section 7008 to the August 2020 coup), Guinea (subsequently assessed to be a coup), and Burkina Faso (noting that the department is conducting a review “for any potential impact on our assistance”). It wasn’t until late February when the State Department shared with the press that it assessed a military coup took place in Burkina Faso and that U.S. foreign assistance had been restricted accordingly.

But the State Department can act quickly, as it did after the military takeover in Myanmar in February 2021. The day after the Tatmadaw took power and began to dismantle the fledgling democracy, State Department officials acted quickly to determine a coup had occurred and Section 7008 restrictions applied. They also quickly set up a press briefing so that senior State Department officials could explain the U.S. government’s assessment to the press and denounce the actions of the Myanmar military as a “grave risk” to the progress that had been made.

The period before the State Department makes a formal assessment that Section 7008 applies can be very awkward for the department’s diplomats and spokespeople. Lawyers typically advise policy clients not to use legal terms of art—even ones like “coup” that are used colloquially—unless they are comfortable that it applies to a given set of facts. Their objective is to preserve maximum flexibility for clients, avoid sending a premature signal that restrictions have been triggered, and preserve the interpretation of the law that they have cultivated over time.

The Egypt Hangover

In recent years, the State Department’s use of the term “coup” has been shaped by the bruising aftermath of Egypt’s July 2013 coup when word choice became a central focus of the policy discussion surrounding U.S. relations with a long-standing strategic partner. Following the 2013 coup, the U.S. government employed semantic gymnastics so as to maintain policy flexibility and avoid what it worried would be an abrupt rupture in bilateral relations. In doing so, it also was forced to eschew a forthright accounting of the facts.

The drawn-out discussions about the 2013 coup created heightened awareness among the press and other outside observers about the potential ramifications of the United States classifying specific events as a coup. It also led to the use of the term at the State Department becoming more fraught, even though simply calling an event a coup does not legally trigger application of Section 7008.

Indeed, before the coup in Egypt, the U.S. government seemed more comfortable with casual use of the word, even when a Section 7008 determination hadn’t been made. In 2009, Honduran President Manuel Zelaya was removed from office and taken to Costa Rica by the Honduran military. Then-State Department spokesperson Ian Kelly said the following when asked about a coup determination for Honduras: “I think, first of all, we’ve said all along that it was a coup. What we’re looking at is whether or not a particular provision, I think it’s Section 7008 of the Foreign Operations … and Related Programs Appropriations Act—whether that particular provision applies.” President Obama also described the events in Honduras to reporters as a coup.

The State Department ultimately determined there was not a “military coup” in Honduras, but made a policy decision to suspend assistance consistent with Section 7008. At the time, the heading of Section 7008 was titled “Military Coups” and actors involved in the Honduran coup included not just the military but also the judiciary and Honduran National Congress. Executive branch lawyers used this to claim interpretive room to assert that it was not strictly a “military coup” for purposes of Section 7008, even though U.S. officials had referred to it as a “coup d’état.” In response to the Obama administration’s decision that Section 7008 was not triggered by events in Honduras, Congress changed the heading of Section 7008 to “Coups D’état” for fiscal year 2010, and for fiscal year 2012 included more expansive language in the appropriations act to encompass situations “in which the military plays a decisive role.”

Coup Hesitancy

The outsized role of security assistance and security cooperation as a tool of U.S. foreign policy has increased the importance of any legal or policy discussions that could lead to the suspension or ending of security assistance. It has also increased scrutiny of events that could lead to such outcomes. As a general matter, U.S. officials in bureaus, embassies, combatant commands, the White House and other components of the executive branch are reluctant to see interruptions in U.S. assistance to a partner country. Such interruptions are almost always perceived as damaging to bilateral relationships and decreasing U.S. influence and leverage at a time of increased great power competition.

Although it’s understandable that the State Department is guarded about using the word “coup,” in light of the above discussion, the inability to use the term and the perceived dillydallying has its own credibility costs and could undermine the usefulness of Section 7008 as a deterrent in the midst of the current uptick in military coups. There is likely no easy fix for this problem. It’s possible that there are some legislative solutions (Congress could require a formal determination to be submitted to the appropriate congressional committees) that would give the executive branch room to use the term more casually even if the law doesn’t apply.

But for now, more transparency through clear communication from the executive branch about the political considerations and lengthy bureaucratic process that accompanies any coup determination could help lead to less confusion as to why the U.S. government doesn’t act quickly and speak plainly about coups. In doing so, it is still unlikely to make this much less awkward before a final determination has been made, but it would help if there were clear acknowledgment of the gaps between the popular understandings of the terms and the narrow statutory requirements in U.S. law.

.jpeg?sfvrsn=ad4bd1de_5)