Congress: Don’t Grant Austin a Waiver, but If You Do, Reform the Process

Congress shouldn’t wave through another recently retired general to serve as defense secretary. But if it does, it must turn this norm-breaking act into an opportunity to restore the United States’s commitment to civilian control of the military.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

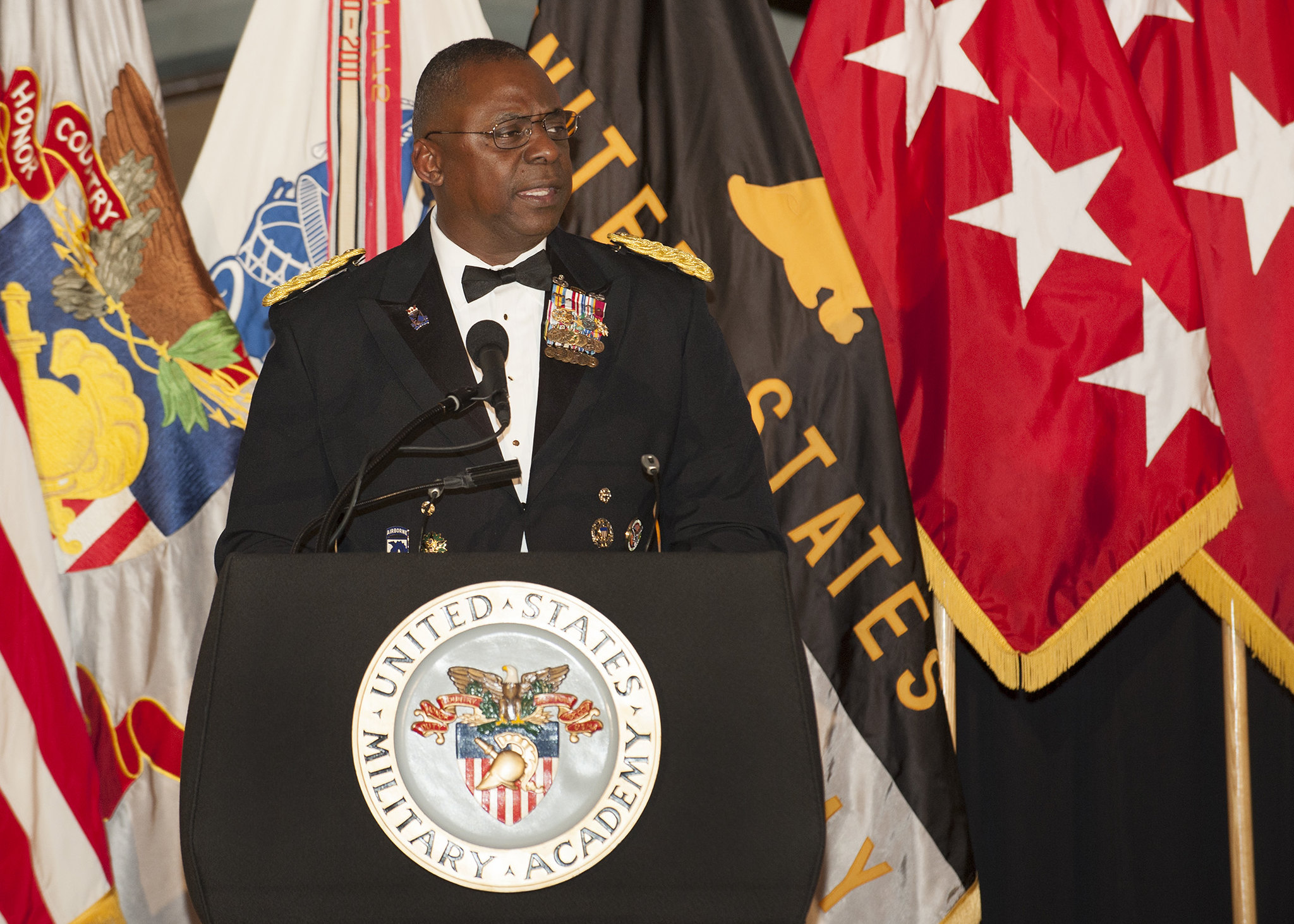

Four years after four-star general Lloyd J. Austin III retired from the U.S. Army, President-elect Joe Biden has tapped Austin to serve as his secretary of defense. Austin’s military career is accomplished, and his nomination, historic. But another roadblock stands in Austin’s way even before Congress can assess his merits for the cabinet position: Congress would first have to grant Austin an exemption from the statutory requirement that retired service members be out of uniform for at least seven years before running the Defense Department.

A congressional waiver would override the seven-year restriction. If confirmed, Austin would be only the third retired general to serve as secretary of defense since Congress unified the military services into a single Department of Defense soon after World War II. As it stands, Congress is poised to consider the issue of Austin’s waiver on an expedited basis. And reports suggest that Congress will grant him the exemption.

This would be a mistake. As we explain below, a waiver would undermine the fundamental principle of civilian control of the military and further erode the delicate division of labor between civilian and military leaders that has been deeply upset by the Trump administration. If, however, Congress does grant Austin a waiver, Congress must secure commitments from him and the Biden administration to restore the United States’s commitment to civilian control of the military. We thus propose a set of reforms that Congress should consider.

The restriction against recent flag officers helming the Defense Department stretches back to the National Security Act of 1947 (which originally required a secretary of defense to have a decade of separation from active duty). The rule arises out of the principle that a healthy democracy requires civilian control of an apolitical military. This principle is foundational—and for good reason. The founders understood the dangers of unchecked military power and its grave potential as an instrument of tyranny; among the grievances against King George III, the Declaration of Independence protests that “He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.”

The founders thus designed a system to ensure that the military served civil society—and not the other way around. The Constitution assigns commander in chief duties to the president, an elected civilian official; reserves to Congress the powers to declare war, raise and support armies, and make rules to regulate the U.S. armed forces; and limits appropriations of money for the Army to two years.

But this constitutional scaffolding alone doesn’t guarantee that civilian leaders will retain control over the military. Civil-military relations require continuous and active maintenance to protect the norm of civilian control; to clearly delineate, as the New York Times editorial board wrote, the “division of labor between military leaders, who are trained to follow orders and win battles, and civilian ones, who are tasked with asking hard questions about why those battles are being fought in the first place”; and to strike the appropriate balance between civilian and military voices in making critical national security and defense decisions and executing those decisions. This “difficult, never-ending task” stems from the paradoxical “civil-military problematique,” as Ryan Grauer explains: “Societies need militaries to provide defense, but those militaries can use their inherent power—directly or indirectly—to exert undue influence on society.”

The fraught nature of the relationship between civil society and the military makes rules hardening civil-military norms, such as the statutory “cooling-off” period before a retired military officer can serve as secretary of defense, all the more critical to uphold. Congress imposed the 10-year restriction in 1947 out of central concerns over civilian control of the military, “closeness among retired officers with serving officers” and “the need for civilian qualifications,” such as budget balancing and overseeing a vast health care system. It takes time to effectively transition from a career of professional military service—more than 40 years, in Austin’s case—to civilian life; it takes time to build a new network of relationships outside of “an all-absorbing institution as total in its way as the priesthood in the Catholic Church,” as Eliot Cohen describes. And while a 2008 change from 10 years to seven was arbitrary insofar as Congress instituted the change without public debate, there is still a meaningful difference between seven years and the four since Austin left the Army in terms of the strength of his nonmilitary network of close advisers, friends and other contacts, as well as his development of the decidedly nonmilitary political skills the Office of the Secretary of Defense demands.

What the seven-year restriction really aims to do, then, is ensure that the secretary of defense comes into the job as a civilian and so directly advances healthy civil-military relations by, for example:

- Mitigating the risk of disproportionate influence from uniformed voices in the secretary’s decision-making, as the secretary must principally provide a wide-ranging, civilian perspective to the president when he or she makes difficult national security and defense decisions and not narrowly provide the views of the armed forces, whom the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff represents; and

- Removing any incentive for military leaders to campaign for the top political job while still in active service, which would both undermine existing civil-military relations and politicize a critically independent institution. Military officers stacked among the ranks of political leadership feature in autocracies and transitioning democracies, not healthy democratic polities.

To be clear, our position is not one presumptively against a retired military officer ever serving as defense secretary. We agree with Dan Maurer that, on the whole, Congress should focus its efforts on a “thoughtful, deliberative appointments process.” And it may be that, despite the risks, exigent circumstances merit an exception to the rule. But in our view, the precept of civilian control is paramount. No matter Austin’s qualifications, no matter how much Biden and Austin profess their “respect and belie[f] in the importance of civilian control of our military and in the importance of a strong civil-military working relationship at [the Defense Department],” if the fact of his appointment would further damage the already endangered state of civil-military norms, Congress should not wave him through.

The immediate historical context of Austin’s norm-breaching nomination urges denying him a waiver. Biden’s call for another waiver so close in time to the last risks letting the exception swallow the rule. And as Biden himself acknowledges, “the civil-military dynamic has been under great stress these past four years.” In the time since Austin has left military service, President Trump has breached norm after norm. He demanded personal loyalty from the military—a nonpolitical institution by deliberate design—calling generals “my generals.” He repeatedly threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act to use military force for political ends and violently suppress nationwide civilian protests. And he purged leadership in the Pentagon to install Trump loyalists. Now, more than ever, the lines between the civilian and military spheres must be reinforced—not further erased.

The tenures of both retired generals who previously served as secretary of defense further stress the need for a defense secretary with sufficient distance from military service. Congress first granted a waiver to Gen. George Marshall for President Truman in 1950, amid the throes of the Korean War. It didn’t do so again for 67 years until Gen. James Mattis for Trump. Both generals’ terms generated problems linked to their recent military service. As Jim Golby recounts, in the face of a civil-military crisis between Truman and Marshall’s former Army peer Gen. Douglas MacArthur concerning Truman’s Korean War policy, “Marshall stood by,” going as far as intervening to try to stop MacArthur’s dismissal for insubordination.

As for Mattis, Congress granted him a waiver in response to the “extraordinary circumstance” of a president “demonstrably unsuitable for the office,” with the hope that Mattis would temper the president’s undemocratic and dangerous impulses. While Mattis did serve as a counterweight to Trump for two years, Mattis’s decisions as the secretary of defense eroded the foundational norm of civilian oversight over the armed forces. For example, he staffed the Office of the Secretary of Defense with active-duty and recently retired military officers, “pushing out both civilian expertise and visibility into the daily goings-on at the Pentagon.” And he relied more on his uniformed former peers than civilians on policy, accelerating the “unhealthy trend” of tilting the balance of decision-making on issues at the center of U.S. defense and national security policy away from civilian leaders. Mattis also hampered congressional oversight and public accountability over military affairs through policies of restricted public engagement and increased secrecy about ongoing military deployments overseas. This rollback on transparency might be favorable from a military perspective, as the less the public—and adversaries—know about the U.S.’s military commitments, the fewer threats to U.S. troops. But as Loren DeJonge Schulman and Alice Hunt Friend underscore, by failing to clearly communicate what troops are deployed where and why, the Pentagon has undemocratically “separat[ed] government action from public preferences,” which will erode public engagement and investment in the country’s military operations and U.S. commitments to global conflicts.

Were it our decision, therefore, we would oppose granting the waiver—precisely because opposition would “reinforce the democratic foundation of our country,” something Biden has indicated is a priority. However, if Congress does grant the waiver, it must convert this norm-breaking act into an opportunity to restore the United States’s vital commitment to civilian control. Members of Congress have begun to probe Austin’s commitments to upholding the role of civilian leadership in military affairs. But Congress can—and should—do more.

Congress should pass a bill alongside an Austin waiver that reinforces civil-military norms by limiting the waiver process, instituting requirements on the front end of the waiver process and/or imposing staffing limitations within the Office of the Secretary of Defense to mitigate risks from granting a waiver. One step could be to eliminate the waiver altogether, thus foreclosing the possibility that a recent military officer serves as secretary of defense. Or, Congress could revert the cooling-off period to 10 years, as it was until 2008.

Congress could also impose additional prerequisites to the front end of the waiver process. First, it could require a detailed report justifying the nomination to trigger the expedited procedures that guarantee congressional consideration of the president’s—or here, the president-elect’s—request. The report should specify the need for the waiver, the nominee’s qualifications, why the nominee’s appointment would not weaken civilian control of the military and how the presidential administration would act to strengthen civilian control. Congress could require that it receive the report before the expedited procedures begin at all, and it could hold hearings to examine the factual record presented therein. In addition, Congress could raise the threshold for approving a waiver to a supermajority, as with the Congressional Budget Act’s 60-vote points of order, which allows Congress to explicitly bypass the act’s rules—but only with a supermajority vote in the Senate.

Finally, Congress could institute staffing restrictions within the Department of Defense as a condition of approving a defense secretary waiver to mitigate the risk of further muting civilian voices in favor of military ones. For example, if Congress votes for a waiver for Austin, it could prohibit recently retired veterans from serving in senior roles at the Pentagon, such as at the deputy assistant secretary level or above.

In his call for Congress to grant Austin a waiver, Biden writes: “Given the immense and urgent threats and challenges our nation faces, he should be confirmed swiftly.” But given the unremitting threats to civil-military relations and their corrosion over the past four years, Biden’s plea cannot overcome the overarching principle that civilian control of the military protects American democracy.

Disclosure: The authors work for Protect Democracy, which has represented Lawfare editors Benjamin Wittes, Jack Goldsmith, Scott Anderson and Susan Hennessey on a number of separate matters.