Congressional Homeland Security Committees Seek Ways to Support State, Federal Responses to the Coronavirus

Congressional homeland security committees heard testimony last week from an array of experts on how Congress can support state and federal responses to the coronavirus outbreak.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

During hearings last week, congressional homeland security committees convened an array of experts and administration officials to advise Congress on how best to support state and federal responses to the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Lawmakers and witnesses also took the opportunity to discuss ways to ensure the U.S. is better prepared to confront future epidemics, including by substantially increasing the amount Washington spends on the infrastructure and programs needed to fight infectious diseases.

On March 4, the House Homeland Security Committee heard testimony from Ngozi Ezike, the director of the Illinois Department of Public Health; Tom Inglesby, the director of the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins University; and Julie Louise Gerberding, the Executive Vice President of Merck & Co. and the former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). On March 5, the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee heard testimony from Ken Cuccinelli, the senior official performing the duties of the deputy secretary of homeland security, and Robert Kadlec, the assistant secretary of health and human services for preparedness and response.

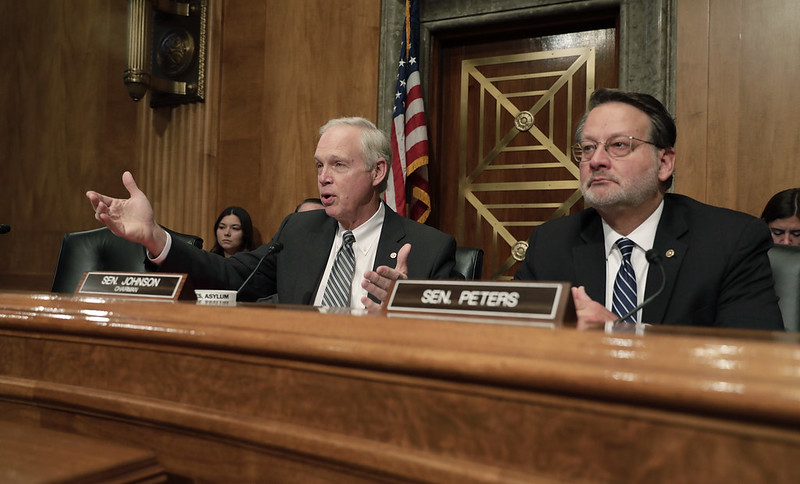

The hearings covered a substantial amount of ground, but throughout both hearings a calm sense of purpose prevailed. Lawmakers were, as Sen. Gary Peters noted in his opening remarks, singularly focused on “keeping Americans safe.” They were not panicked. And but for a fleeting moment in the House hearing, they refrained from engaging in partisan bickering.

At the hearing Thursday before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, Cuccinelli and Kadlec stated that the administration is working with all levels of government and partners in the private sector to aggressively contain and mitigate the outbreak of COVID-19.

That process, Cuccinelli stated, has begun at America’s ports of entry. To minimize the risk of U.S. persons returning to the U.S. spreading COVID-19 to the broader population, the Department of Homeland Security has designated 11 airports to receive people who have been to mainland China or Iran within the previous 14 days, as both countries have been hit hard by the virus. At the designated airports, these individuals undergo proactive screening coordinated by the CDC, Customs and Border Protection, and the Transportation Security Administration. Homeland Security has also heightened its screening at the three land ports of entry that have seen the highest traffic from people who recently traveled to China: San Ysidro, California; Buffalo, New York; and Blaine, Washington. Foreign nationals who have been in China or Iran within the previous 14 days are barred from entering the U.S. altogether, pursuant to two presidential proclamations.

In his prepared remarks, Kadlec argued that America’s health care system is well prepared to respond to the spread of COVID-19. Kadlec explained that in the aftermath of 9/11, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) established the Hospital Preparedness Program to improve the capacity of hospitals around the country to deal with disasters and influxes of patients. Through the program’s grants, states have been able to purchase equipment and supplies to enhance their hospitals’ emergency medical surge capacities. And all 50 states have had to develop Pandemic Plans—a requirement of the CDC’s Public Health Emergency Preparedness Program.

The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority—a component of Assistant Secretary Kadlec’s HHS Office of Preparedness and Response—has been reviewing potential COVID-19 vaccines, working with HHS and the Defense Department to identify technologies suitable to addressing COVID-19, and begun developing medical countermeasures to combat the virus.

Kadlec acknowledged, however, that the administration has faced significant challenges in responding to the viral outbreak, including a nationwide shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as face masks, N95 respirators, gloves and surgical gowns. The assistant secretary noted that his office has coordinated with the CDC and other federal agencies to share information about how to optimize existing PPE and prevent the overbuying of critical supplies (though he did not specify by whom). HHS and other federal agencies, Kadlec continued, are also working to develop acquisition strategies that incentivize manufacturers to expand their production of PPE.

Lawmakers in both hearings expressed concern about the shortage of protective equipment. Sen. Maggie Hassan stated that when public health officials in New Hampshire tried to order additional PPE, they were told it was on backorder until May. Hassan worried that the Strategic National Stockpile—a backup inventory of federally maintained medical supplies reserved for use in public health emergencies—will not have enough supplies to meet states’ needs. In the House hearing, Ezike urged the federal government to evaluate the Strategic National Stockpile well before states near the point of running out of personal protective supplies.

The Illinois official also pushed the administration to inspect the expired PPE that states have preserved in accordance with the PPE Shelf Life Extension Program—an initiative that requires states that receive medical supplies from the Strategic National Stockpile to hold on to expired, “federally supported” supplies until the federal government either extends their expiration date or decides that the materials are unfit for use. If the government inspected such expired PPE now, Ezike argued, it could increase states’ equipment reserves by freeing up supplies still fit for use.

Lawmakers also pressed administration officials for information about the severe shortage of test kits needed to determine whether people have contracted the virus. Kadlec confirmed that the CDC planned to distribute 2,500 test kits to 190 locations around the country; each kit contains 500 tests. Because individuals suspected of having COVID-19 must be tested twice, the kits are capable of testing roughly 600,000 Americans. But the assistant secretary qualified that the tests will not be “immediately available” to the public. Rather, they will become “increasingly available over the next week or two” as the labs receiving them are approved for testing and personnel are trained to administer the examinations.

Kadlec added that the CDC has already distributed 75,000 tests and expanded the “case definition” for COVID-19 to allow more individuals to be tested. But Sen. Josh Hawley indicated that America’s testing capacity remains woefully insufficient. The Missouri senator highlighted the example of South Korea, which is performing more than 10,000 tests a day and has constructed drive-through clinics where its citizens can be tested with ease. Hawley decried the Trump administration’s failure to test at a similar scale. In response, Kadlec offered only that the administration was “scaling up” its testing in public health labs now and partnering with commercial labs that can conduct high volumes of testing, too. Commercial labs should have that heightened capacity in late March, Kadlec specified in an exchange with Sen. Hassan.

In addition to examining shortages in America’s supply of COVID-19 tests and PPE, lawmakers scrutinized flaws in America’s medical supply chain. During an exchange with Kadlec, Hawley contended that too many of America’s medical devices, drugs and pharmaceuticals are manufactured in whole or in part overseas. The senator noted that during global crises, America’s dependence on other countries, particularly China, for those drugs and devices becomes a significant risk. Already, the U.S. has seen reports of potential drug shortages due to Chinese factory closures.

Sen. Ron Johnson focused specifically on the problem of foreign production of the chemicals needed to manufacture American drugs. “I see no reason,” the senator stated, for the U.S. to rely on overseas manufacturing for “drugs approved by the [Food and Drug Administration] for U.S. use. ... I just don’t.” Kadlec acknowledged the problem, saying that the FDA remains in contact with manufacturers, global regulators like the European Medicines Agency, health care delivery organizations, and other entities involved in the medical supply chain to “identify and address any supply concerns” related to “sourcing raw materials for manufacturing drugs.” In an exchange with Sen. Tom Carper, Kadlec suggested that addressing supply-chain vulnerabilities will be critical to improving America’s ability to respond to future epidemics.

While the hearings’ experts and administration officials emphasized the importance of testing and ultimately vaccines in responding to COVID-19, they also stated that an essential piece of the effort to contain the virus will be nonmedical: convincing individuals who are sick or may have been exposed to COVID-19 to stay home from work. Experts were quick to acknowledge and lawmakers repeatedly remarked, however, that taking off from work will place many Americans in significant financial stress. Sen. Kamala Harris noted that two-thirds of low-income workers in the U.S. do not have paid sick leave, and that, for workers in the service industry, missing work can mean not being able to “put food on their table.” The California senator asked the administration officials what they are doing to pressure businesses to give their workers paid sick leave. Kadlec said Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, White House Economic Adviser Larry Kudlow and the National Economic Council are examining the issue.

Later in the Senate hearing, Hassan brought up the federal government’s power during natural disasters to help those in need by providing SNAP benefits and temporary assistance to individuals who are not typically eligible. The senator asked whether the administration has considered offering similar support to Americans during this public health emergency. Kadlec said that HHS and its secretary, Alex Azar, are exploring those options. But the assistant secretary admitted he did not know when a determination would be made on the subject. In the House hearing, Ezike suggested “making funds available to reimburse people” for staying home to ensure they “comply with our public health intervention.”

Many Americans involved in the front-line effort to fight COVID-19 do not have the option of staying home from work, however. In his prepared remarks, Cuccinelli said that the Department of Homeland Security Management Directorate has established a workforce protection command center in order to protect personnel from the Transportation Security Administration, Customs and Border Protection, the Coast Guard, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement who may encounter COVID-19 carriers. And a subgroup of the president’s task force, Cuccinelli added later in the hearing, has been created to deal specifically with protecting the federal workforce.

Effective surveillance and mapping of the viral outbreak will also be essential to effective federal and state responses, officials said. The National Biosurveillance Integration Center, a component of the Department of Homeland Security Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office, has been tracking COVID-19’s spread since it began as an “unidentified viral pneumonia in Wuhan, China on January 2,” Cuccinelli said in his opening remarks.

The CDC has also issued an interim final rule that amends its foreign quarantine regulations and requires airlines to collect “certain data regarding passengers and crew arriving from foreign countries for the purposes of health education, treatment, prophylaxis, or other appropriate public health interventions, including travel restrictions.” The data referenced are individuals’ full name, address while in the U.S., email address, primary phone number and secondary phone number. Under the interim rule, airlines must collect that information and transmit it to the CDC in “within 24 hours of an order by the CDC Director.” The data will be used for “contact tracing,” a process of determining when, where and around whom particular individuals may have come in contact with or spread a communicable disease.

According to the CDC’s justification for the interim final rule, airlines currently take as long as seven days to respond to a CDC request for “passenger manifest information.” And the regulation that presently governs such data requests, 42 C.F.R. § 71.20, does not require airlines to submit the information in a standardized format. The delay in receiving passenger information and the “several business days” needed to put the unstandardized information “into a format suitable for distribution to local health authorities,” the CDC continued, mean that “nearly two weeks” can pass “before health authorities … make the first contact” with a potentially affected person. The interim final rule thus intends to substantially enhance the speed at which the CDC can trace and map the possible spread of a communicable disease and make it easier for the agency to coordinate with local public health officials as it does so.

In an exchange with Peters, the ranking member of the Senate homeland security panel, Cuccinelli noted that this crisis is not the first time the CDC has sought to put such a regulation in place. Indeed, Cuccinelli testified that the agency has tried to do so for 15 years, but airlines have successfully “fought it off.” His remark raised the question of whether airlines will challenge the new interim rule.

The senior Homeland Security official noted two other problems with the regulation. First, there will be a time gap between the CDC’s issuance of the rule and when airlines actually put the systems in place to implement it. And second, many people do not buy their tickets directly through airlines. Heavily trafficked sites like Orbitz and Travelocity, Cuccinelli said, provide even less personal information to airlines than airlines require passengers themselves to provide if they purchase tickets directly on an airline’s site, possibly further undercutting the impact of the CDC’s interim regulation.

States have pursued their own ways of tracking and mapping the spread of COVID-19. Ezike testified that in Illinois, the state’s Department of Public Health has deployed “sentinel surveillance,” which monitors coronavirus levels throughout the state to determine which particular areas are experiencing higher rates of infection and transmission. That mode of surveillance relies heavily on testing, including of individuals displaying flu-like symptoms but who have no known connection to a person or locality infected with the coronavirus.

In the House hearing, Ezike delved deeply into both the additional measures her state has taken to combat COVID-19 and its substantial needs going forward. In her prepared remarks, she repeatedly stressed the need for more test kits and increased funding to relieve the strain Illinois’s COVID-19 response has placed on the state’s coffers. In the first five weeks of the outbreak alone, Illinois has spent $20 million on its response. “[N]ot unexpectedly,” Ezike said, this money “was not in any of our budgets.” When the viral outbreak began, she continued, Chicago had little time to establish screening operations at Chicago O’Hare Airport and a quarantine site there. This cost the city a considerable amount of money, prompting Ezike to urge Congress “to appropriate funds enough to reimburse Illinois and other states, territories and local health departments for the cost associated with COVID-19 response.” This appropriation should include money to pay public health officials for overtime, and provide funding for housing options for isolated people and additional lab machinery, Ezike added during the House hearing.

Data and operations management have also been critical to Illinois’s response. The state’s Department of Public Health closely monitors the availability of airborne infection isolation rooms. Public health officials use the availability statistic as a daily indicator of disease rates in Illinois and as a metric against which to adjust facilities’ surge-capacity estimates. Ezike noted, however, that frequent changes to the situation on the ground have led the state to eschew a “one-size-fits-all” approach and to prioritize the populations that need resources the most—primarily the elderly and people with preexisting conditions.

In cases where individuals have contracted COVID-19 but are not sick enough to require hospital-level care, Ezike said, Illinois public health officials have taken steps to keep them out of hospitals and in isolation. If an infected-but-not-too-sick person lives alone, officials have suggested they stay there. But for infected people who live with roommates or family, officials have tried to find locations where their exposure to other people would be minimal. Motels offer a perfect place for isolation, Ezike stated, because each person has their own space with an individual entrance, and no common lobby or shared air.

To further limit the possibility of COVID-19 spreading in hospitals, Illinois hopes to create drive-through testing sites and establish a sufficiently robust communication system such that someone who thinks they have COVID-19 could speak by phone with the doctor or a hospital and be met by people already wearing personal protective equipment. This would have the additional benefit of protecting Illinois’s front-line health care workers from unnecessary exposure to the virus, as the state cannot afford to lose its doctors and nurses to days of self-quarantine or isolation.

Throughout the crisis, the Illinois Department of Public Health has coordinated extensively with the CDC and other components of the federal government, Ezike said. This has included hours of calls every day with the CDC and onsite support from the CDC’s epidemiological intelligence service officers, who investigate and implement measures to contain the outbreak of infectious diseases.

In his testimony before the Senate, Cuccinelli indicated that Homeland Security officials have spoken with a number of state attorneys general and health commissioners, particularly about their legal quarantine authorities. Those authorities, as Cuccinelli noted and Lawfare explains, differ substantially among states. Cuccinelli qualified, however, that “there is a misconception about the capacity we could put together for quarantining.” While the U.S. has numerous hospitals and local public health facilities, it can handle the quarantining of only small numbers of people, Kadlec confirmed. This is yet another shortcoming that Congress should address to ensure the government is better prepared for epidemics in the future, the assistant secretary concluded.

In the meantime, federal and state governments must contend not only with limited resources to combat the outbreak but also misinformation about its origin, effects and officials’ response. “In the public health community,” Ezike noted, “we are gravely concerned that misinformation and fear will spread faster than the illness itself.” The Illinois official urged the public to rely only on trusted sources to inform themselves about COVID-19, such as the CDC or their state and local health departments.

Inglesby agreed and highlighted the importance of the federal government speaking with a “consistent” voice. While he believed the White House should continue to lead the interagency coordination in response to COVID-19, Inglesby suggested that the CDC and HHS be responsible for daily briefings to the public on COVID-19 “given their many overriding responsibilities in this public health emergency and their strong connections to the public health and health care organizations and leaders that are running the response locally.”

Peters proposed that the administration create a new “.gov” website where people could find in “one coordinated place” what every agency of government is doing to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak. Such a site would offer Americans a trusted and easily accessible way to learn about the virus and make the whole-of-government response digestible in a single location.

A trusted government site would also minimize the extent to which his constituents ended up on websites that “are not accurate” or that peddle products and fear, Peters added. Though the senator said he had already mentioned his proposal to Vice President Pence, Cuccinelli promised to bring it up with the president’s task force and indicated that the idea made good sense.

Ultimately, the hearings sought to begin the long-term work of ensuring that federal and state governments are better prepared to respond to future viral outbreaks. Kadlec argued that any such effort must begin with America’s investing substantially more in its health security. According to the assistant secretary, the U.S. spends roughly $8 billion a year on health security. In contrast, Kadlec said, it spends tens of billions of dollars on aircraft carriers, which are “just one arm of our national defense.” If Congress had invested properly in health security, former CDC Director Gerberding added in the House hearing, it would not have needed to pass a supplemental appropriations package to fund the administration’s response to COVID-19.

This failure to invest in combating health threats and infectious diseases would make more sense, Gerberding continued, if such outbreaks were rare in the U.S. But they are not. In the past two decades alone, the former CDC director observed, the U.S. has witnessed the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), the swine flu (or H1N1), Ebola and the Zika virus. And to this day, the U.S. has failed to complete vaccines for SARS and MERS. “Shame on us,” Gerberding stated, if we make progress on a COVID-19 vaccine, too, and don’t “bring it across the finish line.”

Responsibly prioritizing America’s health security would also require Washington to increase contingency funding for the CDC and the U.S. Agency for International Development, commit to annual contributions to the World Health Organization’s Contingency Fund for Emergencies, and invest directly and consistently in building up the capacities of low-income countries, Gerberding said. The U.S. would be wise, too, to exercise multilateral leadership and persuade its partners and allies to spend more on their own public health resources and preparedness, she added.

At the state level, Ezike called on Congress to increase funding and support for tabletop exercises such as the Crimson Contagion, which convenes multiple states, the federal government and other actors to simulate how they would respond to an emerging and quickly spreading disease. Kadlec added that not enough people are going into public health jobs at the state and local levels, and seemed to suggest that the government should work to incentivize entry into those careers.

In his closing remarks, Johnson seemed clear eyed about the considerable work that lies ahead for Congress. “When the dust settles on this, when we get by this event, we have to prepare better.” That will “require legislation and appropriations.” It will require “thoughtful analysis.” The ball is in Congress’s court.

.jpg?sfvrsn=8588c21_5)