Counterterrorism Copy Cats

.jpg?sfvrsn=77450a02_11)

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

After Hamas-led Palestinian armed groups killed 1,139 people and took more than 250 hostages on Oct. 7, 2023, Israel’s UN ambassador called the attack “our 9/11.” The comparison he made is worth paying attention to. It wasn’t just the cruelty of the events or their magnitude. Israeli authorities invoked 9/11 to legitimize the dramatic show of force they intended in response, just as the United States responded over two decades ago with an invasion of Afghanistan and “shock and awe” in Iraq.

In many ways, the U.S. response to 9/11 didn’t end until August 2021, when the final U.S. troops departed Kabul. At the time of the withdrawal, President Biden said the U.S. would “turn the page on the foreign policy that has guided our nation the last two decades.” But the reality is that the U.S. has not turned the page. The United States has not reckoned with its excesses of force and abuses, and much of the abusive counterterrorism playbook remains in use as official U.S. policy.

There is no good way for the United States to promote democracy and human rights abroad while it remains a model for a militarized counterterrorism-based foreign policy.

Unsuccessful Efforts to Right the Wrongs

After 9/11, the U.S. committed serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, including secret prisons, torture, and unlawful drone strikes. Thousands of civilians were killed or injured, traumatized, and lost their homes and livelihoods. Very few have received an apology or assistance.

The U.S. government’s counterterrorism policies caused harm at home, too. Muslims in the United States faced a range of abuses, from being indefinitely detained as possible terrorist suspects to overly broad material support charges and discriminatory investigations. Muslim “terrorist” suspects were prosecuted without due process, sometimes on fabricated charges, and received unduly long sentences. Muslim communities across the United States were subject to widespread surveillance and militarized policing.

Neither President Obama nor President Biden succeeded in stepping away from war-based counterterrorism policies despite trying to distance themselves from the abuses of the 9/11 response, while President Trump did not even seem to try to address the issue. Obama made some headway by repealing a Bush-era registration program for foreign nationals from 25 Muslim-majority countries. He also issued orders to end torture and close the Guantanamo Bay detention facility. Biden promised to close Guantanamo, too. But today, 30 men remain in indefinite detention there in cruel, inhuman, and degrading conditions.

Efforts to rein in policies that allow for military operations outside of recognized conflict zones also failed. For example, lethal “over-the-horizon” operations remain intact, with armed drones operating outside of public scrutiny and international law. Any moderation of counterterrorism excesses has been around the margins—a small revision here or there to policy texts that allow U.S. forces to operate anywhere at any time with few constraints.

U.S. abuses in the name of countering terrorism—and the subsequent lack of accountability for those abuses—have given government after government cover to behave in similar ways.

Dystopian Echo Chambers

Israel is only the latest country to invoke 9/11. In January 2015, the Paris offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo were destroyed by a firebomb attack after the outlet published a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed. “This is our 9/11,” said Patrick Klugman, then deputy mayor of Paris, as France extended states of emergency, increased surveillance, and enhanced police powers that included raids on Muslim homes, businesses, and mosques.

In May 2023, after protests following the arrest of former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan turned violent, a government official called it Pakistan’s 9/11. Police officers arrested thousands of protesters, and the government charged them under the controversial Anti-Terrorism Act, which multiple regimes have used against critics since 1997. Although most were released, Pakistan’s parliament also boosted the powers of the intelligence agencies, broadened the scope of offenses to try civilians in military courts, and further censored media coverage of the confrontation with Khan.

Within one year of the 9/11 attacks, Human Rights Watch identified at least 16 countries exploiting counterterrorism narratives to crack down on political opponents, persecute religious communities, and explain away human rights criticism. By 2012, over 140 states had enacted counterterrorism laws; 130 of those “contained provisions that opened the door to abuse.” A 2021 German foundation study of counterterrorism laws and measures of G-20 members found they “restrict their [citizens’] personal freedoms … [and] extend the powers of the executive branch … in the name of national security.”

In 2006, 2007, and 2010, then-UN special rapporteur on torture, Manfred Nowak, said he faced difficulties questioning countries on their records due to U.S. policies. “So many countries felt that if the United States is officially torturing, why should not we also torture,” Nowak said, noting that he had received “a clear statement” to this effect from the speaker of Jordan’s parliament.

Meanwhile, the U.S. and its partners applauded each other for their counterterrorism overreach. Just after the 9/11 attacks, then-Secretary of State Colin Powell said the United States had “much to learn” from Egypt’s counterterrorism methods, which included emergency rule, indefinite detention, and military courts against civilians. Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in turn bragged that “new U.S. policies “prove that we were right from the beginning in using all means, including military tribunals[.]’”

A Model for Israel’s Playbook

Soon after the October Hamas-led attack, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called for the world to unite against Hamas just as it had to “vanquish al-Qaeda after 9/11.” Israel’s “counterterrorism” operation in Gaza has resulted in violations of international humanitarian law, including war crimes. More than 40,000, including thousands of children, have been killed as a result of Israeli bombardment and other reasons related to the war.

Israel is also curtailing rights domestically in the name of countering terrorism, though in different ways.

In October 2023, Israeli Communications Minister Shlomo Karhi proposed regulations that would allow Israeli authorities to arrest civilians and journalists, seize property, or remove people from their homes for spreading information “harmful to national morale” or “enemy propaganda.” These regulations were not enacted but were part of the effort to censor media, which ultimately led to the closure of outlets such as Al Jazeera in May 2024 and the temporary shutting down of the Associated Press’s live video feed of Gaza.

In November 2023, the Knesset passed an amendment to the Counter-Terrorism Law of 2016 with a new offense: “consumption of terrorist materials.” Its stated purpose was to tackle “lone-wolf terrorism” and radicalization of individuals through the media. The Israeli human rights group Adalah called it one of the most “draconian” and “intrusive” measures, aiming to police thoughts and intentions. In the month following the Hamas attack, Adalah documented 251 incidents of people being arrested, interrogated, or warned in relation to the Oct. 7 response for “activity that largely falls within the right to freedom of expression,” according to the group.

Clearly, Israel has put this post-9/11 U.S. counterterrorism model into practice—and gone even further in some cases.

On May 20, when the International Criminal Court prosecutor filed applications for arrest warrants against three Hamas and two Israeli leaders, including Netanyahu, the Israeli leader called it a “false symmetry.” He said that this was like issuing an arrest warrant for George W. Bush after 9/11 but “also for Osama bin Laden.”

Never-Ending Counterterrorism

From unlawful drone strikes, to military commissions designed to circumvent due process, to bypassing Congress to provide allies with weapons, war-based counterterrorism is deeply entrenched in the U.S. government bureaucracy. Decisions are made through a counterterrorism lens almost by default.

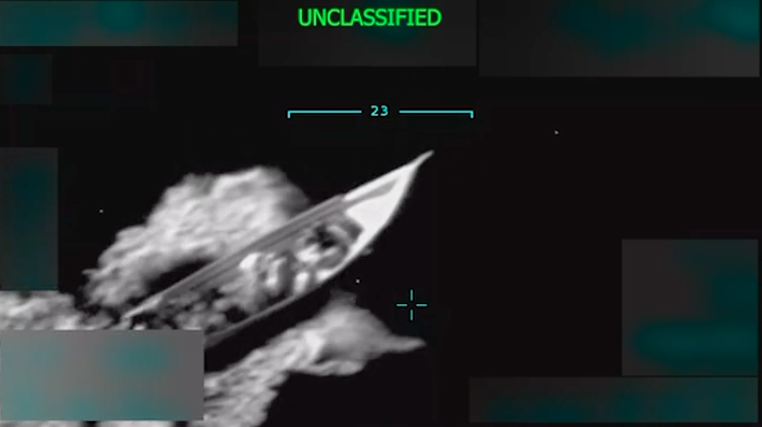

The U.S. response to Houthi attacks on commercial vessels in the Red Sea is a good example. Military strikes on the Yemeni group, later designated “terrorists," were the first, not last resort. There was no public or congressional debate, no presentation of alternatives, and no consideration of the risks to U.S. national security or civilian populations in Yemen where the U.S. strikes were carried out.

U.S. forces still use drone strikes outside recognized areas of armed conflict over two decades after the 9/11 attacks. It’s likely that most Americans don’t even know that these drone strikes are still taking place. Congressional authorizations from 2002 to use force are still being used to target armed groups only tangentially related to al-Qaeda.

One of the most entrenched counterterrorism policies is U.S. military aid to security partners, even since before 9/11. Some partners receiving U.S. military assistance to fight terrorism end up terrorizing their own populations with inappropriate use of force and draconian laws that violate fundamental human rights.

Consider that Nigeria’s security forces, receiving over $2 billion in annual U.S. military assistance to fight the extremist armed group Boko Haram, have regularly injured and killed civilians using U.S.-provided arms. In previous years, and consistent with U.S. law, some Nigerian security force units were barred from U.S. assistance under the Leahy Law due to human rights violations. Israel, however, continues to fall through the cracks. And Nigeria’s Terrorism Prevention Act, created with pressure from the United States for a tougher counterterrorism law, mimics the George W. Bush administration’s legislative overreach. It allows authorities to repress dissent, including by branding critics as suspected insurgents or terrorists.

More examples of U.S. security partners abusing human rights in the name of fighting terrorism can be found in Burkina Faso, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, among others.

The Need for a New Precedent

The Biden administration may wish to “turn the page” from the harm of the “global war on terror.” But if countries are still invoking 9/11 to explain abusive policies over two decades later, it will take more than wishing to get to a new foreign policy based on human rights.

Here are some obvious first steps toward dismantling the 9/11 counterterrorism policy architecture.

Closing Guantanamo would go a long way toward showing the world that the United States has learned from its counterterrorism mistakes, in addition to depriving global leaders the ability to look to the United States as an abusive counterterrorism model. In addition, a reckoning on torture—declassifying information including the release of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence report, ensuring redress and rehabilitation for victims of abuses, and holding those responsible accountable—would help set a new, positive global precedent for taking responsibility. The Biden and any future administrations could end the unlawful use of force outside areas of recognized armed conflict. In its security partnerships, the United States should be promoting human rights, rule of law, and civilian protection.

Sept. 11 has become a date invoked by some governments to justify the unjustifiable. As Elizabeth Miller of the September 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows, an advocacy group founded by relatives of 9/11 victims, poignantly observed on the 20th anniversary: “I hope that one day I find peace, knowing that violence is no longer being perpetrated in any form, in our families’ names.”