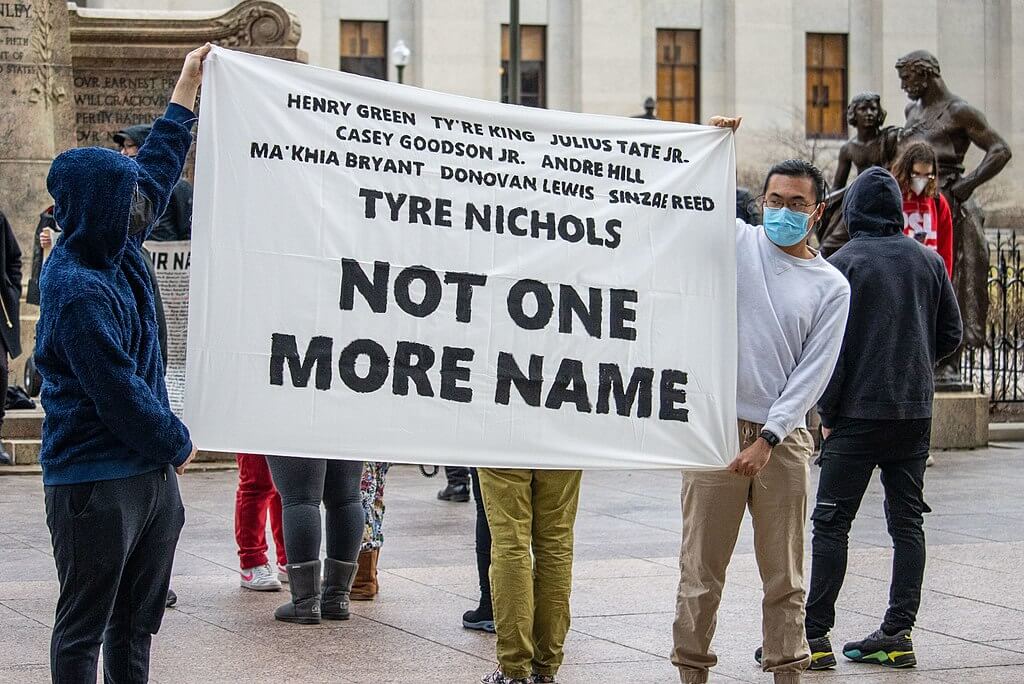

The Culture and Practices of Policing That Killed Tyre Nichols (and So Many Others)

Rather than treat Black and Brown Americans as members of the public they are supposed to se

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

American policing is violent, humiliating, and dehumanizing. It has led to thousands of avoidable deaths. Since the 2020 murder of George Floyd, police killings have only continued, at a rate of over 1,000 people per year. Black people are much more likely to be the victims of these governmental extrajudicial killings. Rather than treat Black and Brown Americans as members of the public they are supposed to serve, the culture and practices of policing treat them as a less-than-human enemy.

Police are occupying forces in many urban Black and Brown communities. People of color too poor to live in a middle class or wealthy neighborhood because of decades of segregation, disinvestment, redlining, and mass incarceration are subjected to heavy and disproportionate surveillance and violence by police. With police helicopters overhead, more police precincts per capita, and plainclothes and uniformed police on patrol in these communities, this occupation sends a message to the public and to police themselves that the people being policed are dangerous. Notably, these militaristic police tactics have not been shown to reduce violent crime.

But police are not in these neighborhoods to keep the peace or to respond to calls for service. If it wasn’t enough to subject people to their constant presence and scrutiny, law enforcement officers stop and search people in these communities on a regular basis. The impact is enormous. Police keep thousands of Americans from going about their daily routines, followed by manual invasions of their bodies, penetrations of their waistbands and pockets, and lifts of their garments often in public. In New York City, innocent people going about their everyday lives have been stopped by police over 5 million times since 2002. In 2011, over 685,000 New Yorkers were stopped in a single year. Police in California stopped 1.8 million people in just a six-month period. In 2018, the Metropolitan Police Department, one of many Washington, D.C., police departments, stopped more than 200,000 people in a city of just over 700,000. Police in all three places were most likely to stop or use violence against Black people, the overwhelming number of whom were innocent of any crime. While perhaps these involuntary interactions between police and civilians might seem utilitarian, safe, and brief in the abstract, in practice these experiences can be violent, terrifying, and traumatic. While pointless from a public safety standpoint, these interactions send a message to police officers that Black and Brown people can be harassed and degraded with impunity.

Police across the country are authorized to stop people for pretextual reasons. As long as law enforcement officers have a legal justification to make a stop, they can use a hunch, caprice, or any other motivation to conduct this contact with a fellow citizen. Police can even stop someone because that person would rather decline the interaction. The ability of the police to stop anyone for whatever reason they want makes many people of color perceive police officers less as public servants and more as abusive stalkers.

It is no secret that during these stops and other interactions, police officers sometimes speak to citizens in unprofessional, disrespectful, and offensive ways. The Department of Justice reports in Chicago, Ferguson, and Baltimore made plain that police commonly used offensive language and even racial slurs in those cities when describing or addressing people of color. My own research documented well over a hundred instances of explicit racial bias by law enforcement officers on social media, text messages, and emails. The Plainview Project proved that thousands of police officers posted racist, homophobic, and misogynistic comments on a single social media platform. Police culture and practice tolerates officers disparaging the people paying their salaries. No other profession would allow its staff to treat its customers in the way the police treat the residents of many communities.

Heavy militaristic police presence, disparaging language, frequent stops and searches based on pretexts, and disparaging language are all evidence that police view Black and Brown people with suspicion and fear. These groups of people are not served by police—they are subjugated by them.

Some laws and policies incentivize the police to engage in these terrifying interactions. For example, some police departments have quotas for arrests, and so contacts with civilians like stop and frisks help officers make their quotas. There are other incentives to stop motorists beyond quotas. Federal funds subsidize highway traffic stops. If police departments do not write tickets or make arrests on highways, then their departments risk losing those monies.

Civil asset forfeiture, and other revenue-generating activity, is another law enforcement policy that drives dangerous interactions between police and American citizens. Stops of people give police an opportunity to seize their property without ever charging anyone with a crime or traffic infraction. In fact, in some years police have taken more from civilians than actual burglars. Memphis’s Scorpion unit—the unit at the center of the Tyre Nichols murder—was lauded recently by Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland for seizing “$103,000 in cash and 270 vehicles” just between October 2021 and January 2022. Civil asset forfeiture encourages officers to see citizens as a source of revenue for their department and incentivizes police officers to come into contact with individuals in case there are items they can seize from them. And in some jurisdictions, the revenue from tickets for traffic violations further motivates police to come into contact with Americans who are simply living their lives. For example, the Department of Justice reported that the fines and fees collected in relation to traffic enforcement in Ferguson, Missouri, where Michael Brown was killed by police, subsidized much of the city government there.

But it’s not just police policies and practices—the culture of police officer hiring also puts Americans in danger. Police officers are overwhelmingly male and young, and current hiring only perpetuates these demographics. While America is diverse in terms of gender, age, and race, its police departments are not. This is concerning—the presence of even a single woman police officer on a scene reduces the chance for violence. Women are less likely to use force and more likely to deescalate an encounter. But women make up less than 13 percent of American police departments’ staff. In addition to gender, age plays a role in the violence inflicted on civilians. Young people in their teens and twenties are often more violent, impulsive, and susceptible to peer pressure, yet police departments hire people as young as 18–21, making those officers a more dangerous cohort. The police officers charged with killing Nichols are all men between the ages of 24 and 32.

The aftermath of the homicide of Nichols also shows that police officers will fabricate their version of events in order to justify their actions or avoid any penalties. The initial police report about Nichols’s interaction with police, written while he was still alive, is riddled with inaccuracies. Unfortunately, there are countless examples of officers lying, and they usually face no consequences for their mendacity. For example, the report about the botched raid that caused Breonna Taylor’s death falsely asserted that she had no injuries. When Buffalo police pushed an elderly man at a protest in 2020, the first police report falsely claimed that he tripped—until video showed he was violently pushed. The police report on the George Floyd case described his death as a medical event and omitted any mention of the officer pressing his knee down on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes. Police misrepresentations are not limited to their police reports. Testifying falsely is so common for police that there is even a term for it: “testilying.” Despite a troubling number of instances of police being exposed for lying, they continue to do it because they have little fear that they will be caught. In fact, in New York City, some officers who lied received promotions.

One well-documented aspect of police culture that protects officers’ misrepresentations, misbehavior, and violence is known as the “blue wall of silence.” This means they do not typically report their fellow officers when they transgress. Even when citizens file complaints and civilian review boards recommend punishment for officers, police departments often lessen the severity of the discipline or ignore it altogether. For example, one study found that only 3 percent of complaints against Chicago police officers resulted in any discipline.

On the rare occasion that police are disciplined, police culture and practice is for problem officers to stay on the force in positions where they interact with civilians. Four of the five officers accused of killing Nichols had previous complaints against them. The officer who killed George Floyd had 18 complaints against him and received discipline for two. The New York Police Department officer who was responsible for Eric Garner’s death had 17 misconduct complaints at the time of Garner’s murder. The officer who shot Walter Scott in the back on videotape had previously been in trouble with his department for using his stun gun on an unarmed person. And the officer who was convicted of killing Laquan McDonald had 29 complaints against him, many for excessive force. The officers responsible for Breonna Taylor’s killing had prior complaints against them as well. Police management and supervision practices fail to hold police accountable and instead embolden them and place them back in a position to harm.

Police culture and practices too often lead the police to harm the people they are supposed to be serving. Police violence is a leading cause of death of young Black men. While many of these deaths, like the tragic death of Tyre Nichols, make headlines, many other injuries are caused by police. For every death caused by police, at least 50 individuals are sent to hospitals due to police brutality. There are many more bruises, bumps, scrapes, and psychological traumas that are never documented.

Nichols’s killing was tragic and avoidable. While police officers have been arrested for his killing, their prosecution will not solve the much broader problem within police policies, practices, and culture that contributed to Nichols’s death. Fundamental and drastic changes to policing—and the criminal legal system more broadly—are needed in order to stop government-funded violence against the people the government is supposed to protect.