The D.C. District Court Upholds the Government’s Geofence Warrant Used to Identify Jan. 6 Rioters

The district court’s Jan. 25 holding green-lights the government’s use of geofence warrants

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On Jan. 25, Judge Rudolph Contreras of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia handed down an opinion in the case of United States v. Rhine denying Jan. 6 rioter David Harles Rhine’s motion to suppress evidence obtained from a geofence warrant.

Searches stemming from a geofence warrant can be likened most succinctly to “fishing expedition[s]”: Law enforcement compels a third-party provider, like Google, to disclose user location history (LH) data of “cell phones in the vicinity of [an] alleged criminal activity under investigation” in order “to narrow the pool” and “fish” out the identity of the criminal suspect. Unlike traditional search warrants, where courts compel a third-party provider to disclose a suspect’s location data after a suspect has been identified, geofence warrants place the cart before the horse. A third-party provider is compelled to disclose LH data of all individuals present in a particular vicinity during an alleged crime before a suspect has been identified.

Geofence warrants fall under Fourth Amendment protections in theory. The government must show probable cause that the geofence area contains evidence of the crime and, with particularity, tailor the scope of the warrant in space and time to leave as little discretion as possible to the whims of law enforcement officers.

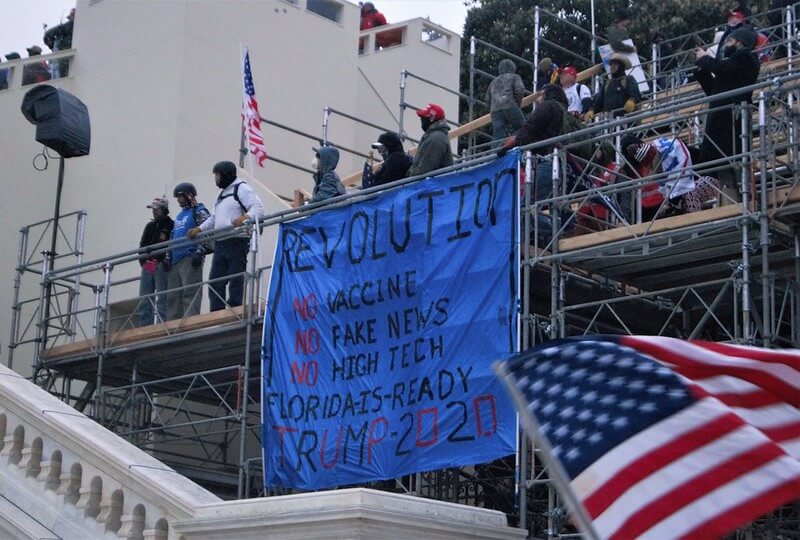

Rhine was among the thousands of rioters who walked off Capitol grounds scot-free on Jan. 6, 2021, leaving FBI agents scrambling to pin down the insurrectionists. Geofence warrants were used to seize Google LH data for individuals “in and immediately around the Capitol between 2:00 p.m. and 6:30 p.m. on January 6, 2021.” Rhine’s location history data was caught in the geofence warrant and led the Department of Justice to level four misdemeanor charges against him: (a) entering or remaining in a restricted building or grounds in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1752(a)(1); (b) disorderly or disruptive conduct in a restricted building or grounds in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1752(a)(2); (c) disorderly conduct in a Capitol building in violation of 40 U.S.C. § 5104(e)(2)(D); and (d) parading, demonstrating, or picketing in a Capitol building in violation of 40 U.S.C. § 5104(e)(2)(G).

Rhine challenged his culpability and filed a motion to transfer venue, a motion for expanded voir dire, several motions to dismiss the charged counts, and a motion to suppress evidence obtained from the warrant because, according to Rhine, the geofence warrant was unconstitutional. The court denied all of Rhine’s motions (save for expanded voir dire, which it partially denied) and, most importantly, upheld the geofence warrant as constitutional.

With so little precedent on what makes geofence warrants constitutional, Judge Contreras’s holding is a breakthrough for the government as it uses LH data obtained through the geofence warrant to level charges against Jan. 6 rioters. More broadly, the case is also instructive for law enforcement as an example of the kinds of Fourth Amendment guardrails that a geofence warrant must have for it to pass constitutional muster.

Facts of the Case

On Jan. 6, 2021, at 2:42 p.m., Rhine—a native of Bremerton, Washington—forced his way inside the Capitol building carrying a blue flag with white stars and white cowbells as well as two knives and pepper spray in his backpack. At 2:57 p.m., Capitol Police searched Rhine, found the knives and pepper spray, and detained him, placing him in flex cuffs with his hands behind his back. At 3:02 p.m., an officer allegedly released Rhine after Rhine agreed to leave the building. One minute later, an unidentified individual cut the flex cuffs from Rhine’s hands, and at 3:04 p.m., Rhine left the Capitol building.

Rhine’s Motion to Suppress Evidence Obtained From the Geofence Warrant

The most interesting part of the opinion is Contreras’s decision to uphold the geofence warrant as constitutional, therefore denying the defendant’s motion to suppress the fruits of the warrant.

In the limited number of written opinions—only one of which is an opinion written by a federal district court (United States v. Chatrie), while seven are magistrate court opinions—geofence warrants frequently fail on two grounds: Either the warrant is not narrowly tailored to the scope of probable cause or the government fails to bake judicial approval into each iterative step of the collection process.

This second reason was the issue in Chatrie. After obtaining a geofence warrant compelling Google to provide anonymized user data, the government failed to get court approval twice: once when it returned to Google requesting a more tailored list of LH data from the initial set and again when it requested that Google unveil the identifying information for selected accounts. The scope of the warrant was also overly broad in time and space. Although the warrant was held to be invalid, the court found suppression to be inappropriate because of the good faith exception, which deems the fruits obtained from an invalid warrant, or “the poisonous tree,” admissible if the “evidence [was] seized in reasonable, good faith reliance on a search warrant.”

Rhine used similar arguments, namely that the warrant used to “fish” him out of the Jan. 6 pool was overbroad and lacked particularity. The government responded in the alternative and added that the warrant was obtained in good faith. The court agreed.

Specifics of the Geofence Warrant Used to “Fish” Out Rhine

In Rhine’s case—in contrast to Chatrie, where law enforcement sought court approval for a warrant in the first stage but not the subsequent stages—the government used a multistep process to seek court approval each time it requested that Google produce a narrower set of user data. The multistep process was as follows:

At step one, Google was to provide the Government with three anonymized lists of devices—a primary list and two control lists. The primary list consisted of devices that Google “calculated were or could have been (based on the associated margin of error for the estimated latitude/longitude point) within the TARGET LOCATION.” … The two control lists were … for time ranges of 12:00 p.m. to 12:15 p.m. and 9:00 p.m. to 9:15 p.m., respectively. … At step two, the Government then was to “review these lists in order to identify information, if any, that [was] not evidence of a crime (for example, information pertaining to devices moving through the Target Location(s) in a manner inconsistent with the facts of the underlying case).” … That process was to include the Government comparing the primary list to the control lists and “strik[ing] all devices” from the primary list that appear on either of the control lists. … At step three, the Government was to “identify to the Court through a supplemental affidavit the devices appearing on the list produced by Google for which it [sought] the Google account identifiers and basic subscriber information.” … If ordered by the court after review of that supplemental affidavit, Google would then be required to “disclose to the government the Google account identifier associated with the devices identified by the government to the Court, along with subscriber information for those accounts.”

A magistrate judge approved the government’s application for a geofence warrant, and Google produced a list of 5,723 unique devices within the time frame and location specified by the scope of the government’s warrant. The government narrowed this initial list to 1,498 devices showing a location point within the Capitol building within the hours specified in the warrant. The government also fished out 37 devices that had “at least one record that [was] located within the Geofence but some part of their margin of error [fell] outside of the Geofence.” For these 1,535 devices, the government filed supplemental affidavits seeking account identifiers and basic subscriber information. The same magistrate judge approved an order compelling Google to unveil the identifying information on the 1,535 devices. Rhine’s device was one of them.

On Nov. 5, 2021, the government submitted an affidavit of probable cause in its application for a warrant to search Rhine. In addition to Rhine’s LH data, the government also received two tips that Rhine had been inside the Capitol on Jan. 6. From the Capitol building’s surveillance footage and upon review of a text message that Rhine had sent one of the tipsters stating, “I witnessed ZERO violence. I saw no ‘proud boys.’ Capitol police removed barriers and let people in,” the government substantiated its probable cause to search Rhine. The magistrate judge approved the warrant request, and on Nov. 9, 2021, the government executed the warrant, seized Rhine’s cell phone, and arrested him.

Was the Warrant Overbroad?

Rhine argues that the geofence warrant exceeded the scope of probable cause and takes issue with the government’s multistep process to compel Google to produce LH data. The government says, not so. Judge Contreras agrees.

Rhine’s objection to the first step of the process stems, in part, from the large quantity of data produced from the “millions of unknown accounts” in Google’s Sensorvault. The court responds that compelling a third party to search its records database would necessarily produce a larger quantity of records than the ones specifically requested. That would not render such a warrant overbroad. Moreover, in the first step, Google produced anonymized LH data, which the court suspects doesn’t implicate Rhine’s Fourth Amendment expectation of privacy because the data did not identify Rhine.

Rhine puts forth similar arguments for step two, including that Google should not have disclosed two additional versions of the primary lists. The data in these lists were based on the data that Google had as it existed on the evening of Jan. 6 and the morning of Jan. 7. Contreras concludes that these are “quarrels with Google.” The government did not compel these actions “even if they were in excess of the warrant’s authorization.” Rhine expresses a second concern with the control lists, which contained anonymized device information for two 15-minute periods at 12:00 p.m. and 9:00 p.m. on Jan. 6. Contreras reinforces the point that the lists were anonymized and “the purpose of using control lists from outside the step one timeframe was to narrow the universe of devices to ensure that supplemental affidavit seeking deanonymization established particularized probable cause.” This narrowing process is critical and “was a significant factor motivating the rejection of the geofence warrants in Chatrie” and three other magistrate court cases.

Next, Rhine criticizes step three for an “unusually broad scope of probable cause.” The court is unconvinced for several reasons. First, the court concedes that “the scope of probable cause was uncommonly large” but for good reason. Jan. 6 was a “unique event” that brought thousands of people to the Capitol grounds. Second, the Capitol building was not open to the public on that day while Congress certified the electoral votes, so individuals whose LH data was fished out in a geofence warrant during that time frame was “evidence of a crime.” Third, probable cause was substantiated by the “unusual abundance of surveillance footage, news footage, and photographs and videos taken by the suspects themselves while inside the Capitol building.” The court finds “more than a ‘fair probability’” that the suspects had smartphones on them while inside the Capitol building, and their devices’ LH would provide evidence of a crime.

Rhine also claims that the warrant’s authorization under step three was overbroad because the government’s efforts to “narrow the primary list at step two were insufficient.” The court has a different interpretation. It finds that the government’s use of control lists to narrow the list of devices in step three was a “reasonable approach” given the large volume of suspects and “well-documented timeline of events indicating when they, as opposed to uninvolved bystanders, would have been present within the Geofence area.” More to this point, magistrate judges have twice held in favor of the government for establishing probable cause even with less stringent limiting procedures. That the government in this case had limiting procedures built into their multistep process undercuts Rhine’s assertion that the government’s efforts to narrow the primary list at step two were insufficient. Moreover, the government’s supplemental affidavit made clear that it sought subscriber information from devices where “‘at least one record … [was] located within the Geofence.’” These measures reduced the initial list produced by Google and the final list of devices the government sought to deanonymize by 73 percent, a significant amount in relative terms.

With respect to the geographic area covered by the geofence warrant, the court underscores that the “geofence area closely… contour[ed] the Capitol building itself, and [did] not include the vast majority of the plazas or grounds surrounding the building.” The devices that were deanonymized “‘ha[d] at least one location associated with the device that [was] within the [Capitol] building.’” For the 37 devices that also had a margin of error associated with their LH data, the court reasons that the “area around the Capitol is unusual for its lack of nearby commercial businesses or residences” and that “extensive road closures west of the Capitol, in anticipation of the rally on the ellipse on January 6, including on Pennsylvania Avenue, reduce the likelihood that any stray cars would have been picked up in the geofence error radius.”

Concerning the “four-and-a-half-hour” time frame of the geofence warrant, the court finds the time parameter reasonable because the “criminal activity occurred over a longer period of time.”

Taken together, the court holds that the warrant was not overbroad. Rhine’s efforts to strike down the warrant as unconstitutional now hinge on the issue of particularity.

Did the Warrant Include Particularized Probable Cause?

Rhine’s main argument that the warrant is not particular enough—and, therefore, unconstitutional—contends that it “vested too much discretion in the Government.” Rhine cites two magistrate cases claiming that “the Court must be more involved in narrowing at steps 2 and 3.” The court was unmoved by Rhine’s argument, saying that “the terms of the initial warrant precluded disclosure of deanonymized device information except after separate order of the court based on a supplemental affidavit” (emphasis added).

The Good Faith Exception and Rhine’s Reasonable Expectation of Privacy

Judge Contreras does not dwell on the issue of the good faith exception because he concludes that the warrant was constitutional: The government had a particularized probable cause to compel Google to produce LH data from Jan. 6 and, later, to search Rhine after Google revealed his identifying information. Insofar as Rhine alleges that Google responded excessively to the government’s warrant request by producing data beyond the scope of the warrant, the court does not project those actions on the government and assume bad faith.

The court also does not reach a determination on the issue of whether Rhine had a reasonable expectation of privacy over his location inside the Capitol building or his LH data because it denies Rhine’s motion on other grounds. Instead, it reinforces Supreme Court holdings in Riley v. California, which “emphasized the central role of the warrant in safeguarding the ‘privacies of life’ contained on modern cell phones,” and Carpenter v. United States, which held that “‘individuals have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the whole of their movements” and asserted that “‘[a] person does not surrender all Fourth Amendment protection by venturing into the public sphere.’”

***

As prosecutors continue to pursue Jan. 6 rioters, 948 of whom have already been charged, this holding is significant. It green-lights the government’s use of geofence warrants to pin down the insurrectionists and use the fruits of the warrant as evidence of culpability. Further, it provides a clear framework for the kinds of Fourth Amendment protections the geofence warrant application must meet to be upheld as constitutional.