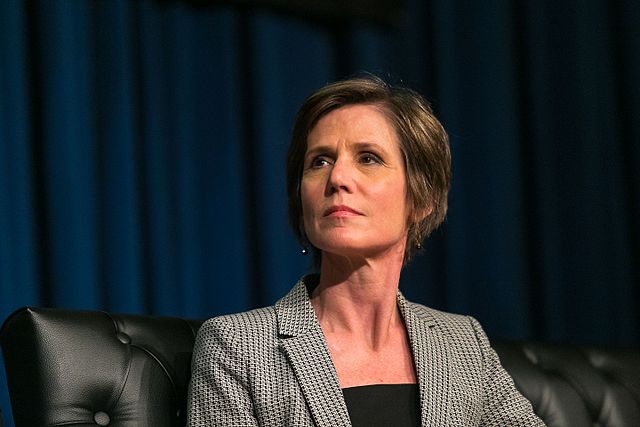

Did the Justice Department Try to Keep Sally Yates from Testifying?

This morning, the Washington Post reported that the Justice Department sought to prevent former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates from testifying before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) as part of the committee’s investigation into Russian interference in the presidential election.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

This morning, the Washington Post reported that the Justice Department sought to prevent former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates from testifying before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) as part of the committee’s investigation into Russian interference in the presidential election.

According to the Post, the department informed Yates that many of the topics on which she was set to testify, including former National Security Advisor Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn’s contacts with the Russian ambassador to the United States, were likely protected by executive privilege. Yates’s lawyer responded with letters to Acting Assistant Attorney General Samuel Ramer and White House Counsel Don McGahn asserting that Yates’s testimony was not privileged.

Yates had been scheduled to testify in an open hearing before HPSCI today, along with former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper and former CIA Director John Brennan. However, on Friday March 24th, the day after Yates’s lawyer mailed his letter to Ramer and the same day that the letter was sent to McGahn, HPSCI Chairman Devin Nunes canceled the committee’s scheduled open hearing in which Yates was set to testify. The Post also reports that by the day before Nunes canceled the hearing, both Yates and Brennan had informed government officials that their scheduled testimony on Tuesday would likely contradict statements by the White House.

Nunes originally announced that the open hearing with Yates, Brennan, and Clapper had been canceled to make way for a closed hearing with testimony from FBI Director James Comey and NSA Director Admiral Michael Rogers in response to Nunes’s hazy concerns about possible incidental collection of Trump transition team communications. Yesterday, however, Nunes stated that the closed hearing had been canceled as well.

HPSCI Ranking Member Adam Schiff has suggested that Yates’s response was connected to Nunes’s decision to cancel the hearing. Earlier reports indicated that Nunes publicly declared the hearing’s cancellation without first informing Schiff or the other members of the committee, and Schiff stated publicly in a press conference following Nunes’s announcement of the canceled hearing that Nunes had previously tried to cancel or close the hearing, only to face pushback from Schiff.

The latest Post report is particularly noteworthy given concerns in recent days over Nunes’s possible coordination with the White House regarding his series of public disclosures on incidental collection. Yesterday, CNN reported that Nunes was seen on the White House grounds the night before his twin press conferences on March 22nd. Additionally, in his press conference on Friday, Schiff also suggested that Nunes had canceled the hearing after “strong pushback from the White House” following the first HPSCI open hearing, asking, “What other explanation can there be?”

Schiff, who last night called on Nunes to recuse himself from the committee’s investigation, has released the following statement in response to the Post’s story:

Today, the American people should have had the benefit of an open hearing, in which they would have heard from former Director of National Intelligence Clapper and former CIA Director Brennan about the Russian effort to meddle in last year’s Presidential election. The open hearing last week provided the public the first acknowledgement of an FBI investigation into potential coordination between the Trump campaign and the Russians, a direct repudiation of the President’s claim that he had been wiretapped by is predecessor, and also the most extensive discussion to date of how the Russians accomplished this unprecedented intrusion into the nation’s electoral process. Today’s hearing would have built upon that understanding, but it was unfortunately and abruptly canceled.

Today’s hearing would also have provided the opportunity for former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates to testify about the events leading up to former National Security Advisor Flynn’s firing, including his attempts to cover up his secret conversations with the Russian Ambassador.

We are aware that former AG Yates intended to speak on these matters, and sought permission to testify from the White House. Whether the White House’s desire to avoid a public claim of executive privilege to keep her from providing the full truth on what happened contributed to the decision to cancel today’s hearing, we do not know. But we would urge that the open hearing be rescheduled without further delay and that Ms. Yates be permitted to testify freely and openly so that the public may understand, among other matters, when the President was informed that his national security advisor had misled the Vice President and through him, the country, and why the President waited as long as he did to fire Mr. Flynn.

The White House has denied taking any action to prevent Yates from testifying and calling the Post story “entirely false.” The administration appears to be slicing words very finely here, arguing that the White House did not “block” Yates’s testimony because it did not respond to Yates’s lawyer’s letter to McGahn, which asserted that the lawyer would conclude that the White House did not intend to assert executive privilege if he did not receive a response by Monday March 27th. Of course, Nunes canceled the hearing on Friday March 24th, rendering any such determination by the White House moot after that point. Nunes’s spokesman has also denied any communications between the Congressman and the White House regarding Yates’s testimony, asserting that “we still intend to have her speak to us.”

The letters from Yates’s lawyer, David O’Neil, are available here, along with the Department of Justice’s letter of March 24th responding to O’Neil’s message to the Acting Assistant Attorney General.

Though the original communication between the Justice Department and Yates regarding executive privilege has not been made public, the March 24th letter from the department in response to O’Neil gives us a sense of the government’s argument. According to the letter, Yates’s testimony on “communications she and a senior Department official had with the Office of Counsel to the President [meaning White House Counsel Don McGahn]” would “likely [be] covered by the presidential communications privilege and possibly the deliberative process privilege.” In his initial letter to the Justice Department, O’Neil also characterizes the department’s argument as holding that “all information Ms. Yates received or actions she took in her capacity as Deputy Attorney General and Acting Attorney general are client confidences that she may not disclose absent written consent of the Department.”

O’Neil’s rebuttal, as expressed both in his initial letter to the Justice Department and in his second letter to McGahn, is twofold. First, he argues that it’s not clear whether Yates’s possible testimony about “the Department’s notification to the White House of concerns about the conduct of a senior official” (presumably, Flynn) would be covered by either the presidential communications privilege or the deliberative process privilege, and that the Justice Department’s invocation of attorney-client privilege is “overbroad, incorrect, and inconsistent with the Department’s historical approach to the congressional testimony of current and former senior officials.” Second, O’Neil argues that even if it were covered, the privilege has been waived given that “multiple current senior administration officials have publicly described the same events.”

For those who are concerned about all of these privilege claims, here’s a brief explainer.

Executive Privilege

In congressional investigations, the executive branch can assert constitutionally based executive privilege, which encompasses two basic types of privilege: deliberative process privilege and presidential communications privilege. Both are intended to protect the separation of powers and prevent congressional interference in executive decision-making.

The deliberative process privilege may be asserted by the executive branch more generally, not just the President. But it applies to a relatively narrow set of information relating specifically to decisionmaking. If there is underlying factual information, the executive branch may be required to disclose that information, separating it from the privileged information. And for information that isn’t covered by the deliberative process privilege, the President may attempt to assert the presidential communications privilege. That privilege applies to a narrower set of actors—the President and his close advisors—but a broader set of information. Neither privilege, however, is absolutem as both may be overcome by a sufficient showing of need for the information.

- Deliberative Process Privilege

The deliberative process privilege protects not just presidential communications or communications proximate to presidential decisionmaking, but executive branch documents more generally. However, it protects only pre-decisional material that was actually part of the deliberative process. The executive is entitled to protect the back-and-forth of that process that leads to an agency action. This privilege is most typically invoked in Freedom of Information Act litigation.

The deliberative process privilege is not absolute and can be overcome by a sufficient showing of need for the information. Notably, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals has acknowledged that “where there is reason to believe the documents sought may shed light on government misconduct,” the privilege is commonly overcome. Indeed, congressional investigations rely in these circumstances on being able to overcome the deliberative process privilege.

While the Department of Justice letter asserts that Yates’s communications with McGahn were “likely” covered by the presidential communications privilege, it writes only that those same communications were “possibly” covered by the deliberative process privilege.

- Presidential Communications Privilege

Under United States v. Nixon, the President is entitled to assert privilege over presidential communications—that is, communications relating to certain sensitive presidential decisionmaking. But the privilege is not absolute. In Nixon, the Supreme Court held that if the presidential assertion of privilege was based on general confidentiality rather than a claim about specific military or diplomatic sensitivity of the materials, a subpoena in a criminal prosecution could defeat the privilege.

In 1997, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals broadened the scope of the presidential communications privilege to include documents prepared by presidential advisors in the course of offering advice to the President. The case in question arose in the prosecution of President Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Agriculture, Michael Espy.

The Justice Department’s letter indicates that the department is seeking to assert presidential communications privilege over Yates’s communications with White House Counsel Don McGahn, rather than with Trump himself. But the D.C. Circuit determined in the Espy case that the presidential communications privilege extends to advisors with “operational proximity” to the president:

Not every person who plays a role in the development of presidential advice, no matter how remote and removed from the President, can qualify for the privilege. In particular, the privilege should not extend to staff outside the White House in executive branch agencies. Instead, the privilege should apply only to communications authored or solicited and received by those members of an immediate White House adviser's staff who have broad and significant responsibility for investigating and formulating the advice to be given the President on the particular matter to which the communications relate (emphasis added).

It seems likely that McGahn, acting in his role as White House Counsel and advising Trump on how to handle a congressional investigation into the conduct and firing of his formal national security advisor, would fall into the category of persons whose communications are covered.

This privilege would not, however, apply to Trump’s actions before he became president. Insofar as the information or testimony subpoenaed related to the campaign, the privilege would offer no protection.

- Attorney-Client Privilege

The March 24th Department of Justice letter does not itself raise the question of attorney-client privilege. However, O’Neil’s March 23rd letter to the department, to which the March 24th letter is responding, refers to the department’s “position that all information Ms. Yates received or actions she took in her capacity as Deputy Attorney General and Acting Attorney general are client confidences that she may not disclose absent written consent of the Department.”

The Clinton administration invoked attorney-client privilege in a handful of cases related to the Starr investigation and involving attorneys serving in the Office of White House Counsel. In In re Bruce R. Lindsey (Grand Jury Testimony), the D.C. Circuit found that this privilege could not be invoked before a grand jury, and the Eighth Circuit reached the same conclusion in In re Grand Jury Subpoena Duces Tecum.

While the case law is limited, therefore, it appears relatively clear that executive branch officials may not invoke attorney-client privilege before a grand jury. But the question of whether the executive branch may invoke this privilege before Congress—which the Trump administration may have had to do in this case, had Nunes not canceled Yates’s hearing—is more open. There is little case law on the subject; furthermore, attorney-client privilege stems from common law and not from Article II of the Constitution, as the presidential communications privilege and the deliberative process privilege do. As such, the executive can assert no constitutional interest in maintaining privilege.

The congressional committee in question can decide whether or not to accept an executive branch claim of attorney-client privilege on a case-by-case basis. Theoretically, if Congress were to reject an invocation of this privilege, the executive branch could bring the matter before a court. However, given hesitance on both sides to engage in litigation on this sensitive question of separation of powers, this rarely happens.

For attorney-client privilege to be invoked, of course, there must be an attorney acting in the interests of a client. And while the Attorney General often acts as the President’s lawyer, he or she can act in other capacities as well—for example, in leading an investigation into the White House, as Acting Deputy Attorney General Dana Boente is now doing. In order to judge whether attorney-client privilege applies in Yates’s case, we would have to know which of Yates’s communications the Justice Department seeks to apply the privilege to and what capacity Yates was acting in when those communications took place.