Does Trump’s Involvement in the Cohen Payments Constitute an Impeachable Offense?

In a court filing submitted last week to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Southern District of New York, federal prosecutors alleged personal involvement by the president of the United States in the commission of a felony. During the 2016 campaign, they wrote, Michael Cohen—then a lawyer with the Trump Organization—both arranged for and personally made a series of payments to purchase the silence of two women who might have gone to the press with stories of their affairs with Donald Trump.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

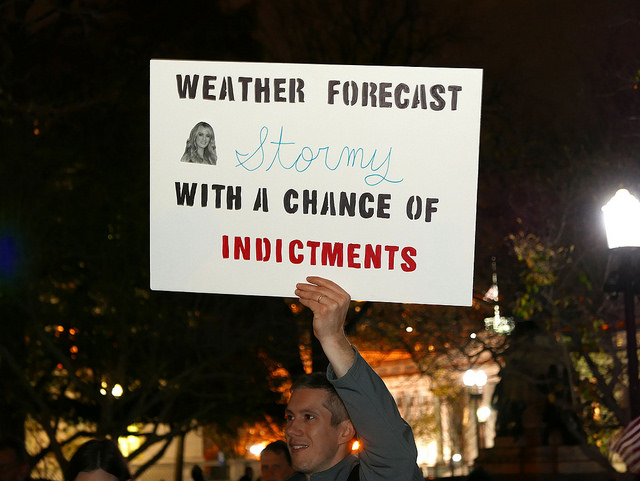

In a court filing submitted last week to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Southern District of New York, federal prosecutors alleged personal involvement by the president of the United States in the commission of a felony. During the 2016 campaign, they wrote, Michael Cohen—then a lawyer with the Trump Organization—both arranged for and personally made a series of payments to purchase the silence of two women who might have gone to the press with stories of their affairs with Donald Trump. Cohen pleaded guilty in August 2018 to violations of campaign finance law in arranging the payments to Karen McDougal and Stephanie Clifford, better known as Stormy Daniels. Now, months later, the government has written in Cohen’s sentencing memo that the president’s former fixer “acted in coordination with and at the direction of Individual-1”—referring, of course, to Trump.

This account of the president’s actions is one that he allegedly went to great lengths to hide in order to protect against serious, perhaps lethal, damage to his 2016 campaign. If the conduct described in the memo was carried out in violation of the campaign finance laws with the requisite state of mind, it could be criminal. But is it impeachable?

This question quickly spirals into an array of thorny subsidiary questions: if the president were to have committed such an offense, would the House of Representatives be driven to impeach him, or, because the institution answers only to itself for this choice, could it exercise quasi-prosecutorial discretion and decline to initiate proceedings? (Nadler drew a line between impeachable conduct and conduct “important enough to justify an impeachment.”) If the Justice Department stands by its guidance that presidents cannot be indicted while in office, to what extent should Trump be worried about the possibility he will face charges immediately after departing office? And by what standard of proof should the House weigh the evidence if it were to consider potential impeachable offenses prior to any indictment?

These are important issues, but they are beyond the scope of what we can discuss here. We mean instead to focus on the germinating question of whether—if evidence were to be provided to satisfy the appropriate standard of proof—a direct instruction by Donald Trump for Michael Cohen to coordinate payments to McDougal and Daniels, with the intention of preventing the two women’s stories from reaching publication and endangering the candidate’s chances of election, would, in and of itself, fit the definition of high crimes and misdemeanors for which a president can be impeached.

It is not a simple case. But ultimately, we believe the conduct at issue would be impeachable.

Charles Black writes in his authoritative “Impeachment: A Handbook” that, while a president’s conduct need not fit the terms of the criminal code in order to be impeachable, every criminal offense does not necessarily justify impeachment. Black also notes, however, that “most of the wrongful acts that have been seriously charged against an incumbent president are regular crimes.” And indeed, the House of Representatives has incorporated a statutory hook each time it has seriously weighed articles of impeachment. So while it would be a mistake to confine any discussion of impeachment to criminal conduct alone, considering Trump’s potential liability for the campaign finance violations to which Cohen has pleaded guilty is a reasonable starting point. As Jane Chong wrote on Lawfare, “law is the North Star of impeachment discourse.”

The Cohen sentencing memo does not explicitly allege the commission of a crime on Trump’s part, nor does it make an effort to establish the requisite state of mind: prosecutors would need to show that Trump had “knowingly and willfully” violated the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) in order to bring charges, though the Justice Department recently relaxed the standard for how detailed a knowledge of the relevant law the defendant must have. This leaves the president with at least two defenses for his alleged role in directing Cohen to make the payments. He could argue that he did not know the payments were illegal. Or Trump could argue, as he already has on Twitter, that the payments were “a simple private transaction” that would have been made regardless of the election—the defense successfully used in the John Edwards case.

The president has indicated some interest on one other defense, namely, that if Michael Cohen, as his lawyer, stumbled into violations of the campaign finance laws, the violations were only civil in character and the error—and any liability—was his. This claim, while not fully clear, suggests an “advice of counsel” defense. The difficulty is that there is no evidence that the president was relying on Cohen’s advice on campaign finance law issues—or on any legal advice at all. And Cohen’s guilty plea indicates that, at the very least, Cohen himself understood the payments to both hinge on the election and to violate the campaign finance law.

The president’s lawyers might be concerned about his potential liability in several different forms. Prosecutors might directly charge an individual in Trump’s position as a candidate of his campaign directly under FECA, on the same charges as Cohen, and also under, first, 18 U.S.C. § 371 for conspiracy to defraud the United States through impeding the Federal Election Commission in carrying out its duties, and second, causing false statements under 18 USC § 1001 and 18 USC § 1519, by causing the campaign to file false FEC reports. (The Justice Department’s manual on “Federal Prosecution of Election Offenses” specifically notes that § 371 may be used to prosecute cases in which a FECA violation results in false information being provided to the FEC and/or “was committed in a manner calculated to conceal it from the public.”)

The Justice Department does not lightly charge criminal violations of the federal campaign finance law. It shares enforcement jurisdiction with the Federal Election Commission and more frequently than not defers to the agency’s civil enforcement authority—even in cases in which there is clear “knowing and willful” intent to break the law. The FEC has the authority to charge such cases civilly but seek aggravated penalties for the “knowing and willful” misconduct. The sign that Justice Department chose to proceed with criminal law enforcement in the Cohen case is an indication of the seriousness of the offense.

The payments to which Cohen has pleaded guilty to making to secure the silence of Daniels and McDougal—$130,000 paid to the former and $150,000 to the latter—well exceed not only the $2,000-per-year threshold at which violations of campaign finance law become crimes, but also the amounts at issue in other recent high-profile campaign finance prosecutions involving $73,000 and $90,000, respectively. And the Cohen charges incorporate three of the core provisions of the law to which the Justice Department looks in assessing the significance of a violation: the prohibition on corporate contributions to candidates, the enforcement of the individual contribution limits and public reporting requirements.

What most drives these prosecutions is the evidence of aggravated disregard for the law, typically reflected in complicated schemes to conceal the illegal activity from regulators and the public. The election offense manual makes clear that a key consideration in bringing criminal prosecution is knowing and willful misconduct reflected in "an attempt to disguise or conceal financial activity" regulated by the campaign finance laws. Along these lines, prosecutors have detailed the elaborate, if clumsy, steps that Cohen took—allegedly at the president’s direction—to set up shell companies and enter into secret agreements with American Media Inc. to hide their spending arrangements. And notably, he took these actions at his legal peril even though the campaign’s own general counsel—recently-departed White House Counsel Don McGahn—was a campaign finance expert and a former chair of the Federal Election Commission. If either Cohen or the president had cared to look into the legality of the matter, McGahn’s advice was presumably ready at hand.

Suffice to say that there is plenty of material on the table to suggest involvement by the president in a serious crime. Cohen’s plea is not, as Sen. Rand Paul has commented, a technicality resulting from a mere “over-criminalization” of campaign finance.

Of course, not all crimes would justify the constitutional remedy of ouster from office. Black writes that a president could not be impeached for assisting a White House aide in concealing possession of marijuana. Less fancifully, while not indicted for his actions in the Lewinsky matter, President Clinton entered into what the New York Times rightly characterized at the time as “what amounts to a plea bargain deal,” which required him to acknowledge culpability, accept suspension of his law license and pay a fine—but the Senate declined to convict him for his offense. The sweeping criminality of the case against President Nixon, on the other hand, convinced congressional Republicans that they could no longer protect him from impeachment, and only a pardon spared him from criminal prosecution following his resignation from office.

Like Watergate, Trump’s case concerns the president's alleged involvement in or cover-up of illegal activity intended to enhance his chance of winning an election. As the House Judiciary Committee articles of impeachment in the Nixon matter state, serious misconduct in the pursuit of electoral success implicates the president "in violation of his constitutional oath to faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and to the best of his ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution…" Here it is useful to quote the Cohen sentencing memo: the payments orchestrated by the defendant were serious in large part because they were meant to “deceive[] the voting public.”

Writing in 1973, Black argued that an impeachable offense must be something that is “extremely serious,” which “in some way corrupt[s] or subvert[s] the political and governmental process,” and which is “plainly wrong … to a person of honor, or a good citizen.” In his recently published supplement to Black’s “Handbook,” Philip Bobbitt affirms the view that “as a matter of constitutional law, a conspiracy to pervert the course of a presidential election … is an impeachable offense.” The behavior alleged of Trump in conspiring to deceive the public through criminal violations of the campaign finance law would seem to fit the bill.

Watergate, of course, concerned Nixon’s efforts to interfere with an election cycle in which he was the incumbent. Misconduct by Trump during the campaign would have taken place before he was elected—which raises the more complicated question of whether such conduct is properly considered in an impeachment proceeding. As Michael Gerhardt has written, “no one has ever been impeached, much less removed from office, for something he or she did prior to assuming an impeachable position in the federal government.”

But that does not necessarily foreclose such an impeachment. Our colleague Andrew Kent noted George Mason’s comment during the Constitutional Convention that a president "who has practised corruption & by that means procured his appointment in the first instance” might properly be impeached. More recently, Cass Sunstein has also written that the procurement of office by improper means could merit impeachment. Gerhardt, for his part, suggests that in weighing such an impeachment Congress might consider “the seriousness of the misconduct, its timing, the relevance of the offense to the election or confirmation, the link between a misdeed and an office, and the proximity of the next relevant election (Congress might prefer to let the voters decide, if possible).”

Given the focus suggested by Gerhardt on “the relevance of the offense to the election,” it is worth noting the assertion in the Cohen sentencing memo that Cohen believed the facts he was striving to conceal "would have had a substantial effect” on the 2016 election. Such a belief turned out to be reasonable in light of the Hollywood Access tape, many thought would be potentially fatal to Trump’s campaign when it initially surfaced. In fact, according to the criminal information, Cohen orchestrated the payment to Daniels on Oct. 8, 2016, the day after the Washington Post first released audio of the tape; the Wall Street Journal has reported that the Post’s story was the “trigger” in Cohen’s coordination of the Daniels payment.

In this respect, the president's actions as described in court documents speak for themselves. According to the sentencing memo, he orchestrated the illegal actions and directed and coordinated them with Cohen. His alleged personal involvement, and the elaborate steps taken to conceal the information, reflect the importance that he and his campaign seem to have attached to keeping the Daniels and McDougal accounts off the public record and out of the public debate.

Nevertheless, however politically harmful Trump and Cohen might have feared revelations of the candidate’s affairs with Daniels and McDougal could be, it is probably unknowable to what extent the silence of those women actually affected the election. For that reason, the stronger case for the Daniels and McDougals payments as an impeachable offense may rest on the fact that the campaign finance violations actually continued into Trump’s presidency. In the arrangements to fund concealment of Trump’s extramarital affairs, according to the sentencing memo, Cohen advanced funds that the Trump Organization repaid only in installments. The repayment schedule extended into 2017, at $35,000 a month. (The criminal information in Cohen’s case indicates that Cohen submitted his first invoice on Feb. 14, 2017, when Trump was almost a month into his presidency.) The balance owing at any given time—including during periods of the Trump presidency—constituted an ongoing illegal contribution by Cohen. And while repayment mitigates violation, it does not cure it—meaning that the violations persisted, unaddressed, during this presidential term.

Over the entire period, the Trump campaign’s reports on public record continue to omit these payments. In fact, having long denied any involvement in the payments to Daniels, Trump chose to disclose the reimbursements to Cohen for those expenditures on his personal financial disclosure statement filed as an elected executive branch official—in keeping with his retooled defense that this was only a “private transaction.”

This is a key point. The offense, if true, was serious. It may well have played a role in securing Trump’s election, and some portion of it continued for the president’s first year in office. But it must also be considered alongside the ongoing effort during the Trump administration to publicly conceal the scheme, in which Trump participated as president. Speaking on Air Force One in April 2018, Trump told the press that he had no knowledge of the payments to Daniels. A month later, after his lawyer Rudy Giuliani stated publicly that Trump had repaid Cohen for his work regarding Daniels, Trump later allowed some knowledge of the payments in a Twitter statement, though he did not say whether he was aware of them at the time. In July 2018, CNN published a tape of Trump and Cohen apparently discussing the payment to McDougal—after Trump had denied any relationship with McDougal. The overall picture is one of a White House that has gradually weakened its previously categorical denials over time as more and more evidence has come to light.

It is at this point that we look away from law as the North Star, as Chong put it, and move into the realm of conduct that, regardless of its legality, nevertheless may be impeachable. It is not a common law or statutory crime to lie to the American people. But it is worth remembering that Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr cited Clinton’s dissembling to the public regarding his relationship with Monica Lewinsky in his impeachment referral provided to the House of Representatives, though the House declined to take up that article of Starr’s draft. In the Watergate case, however, the House Judiciary Committee specifically cited lies to the public in an article voted against Richard Nixon. As Bobbitt puts it, impeachment is redress for “constitutional crimes”—and the precedent shows that lies told by a president may constitute such crimes. If there is uncertainty over whether coordination of the payments in and of themselves would constitute high crimes and misdemeanors, the campaign finance offenses coupled with Trump’s flat-out, repeated denials of knowledge, much less involvement, push the matter as a whole across the line.

The importance of Trump’s involvement in the substantive campaign finance violations to which Cohen pleaded should not be diminished in an eventual impeachment proceeding. Ultimately, however, any such proceeding will surely not center on the Cohen payments alone—simply because of the sheer volume of potential high crimes and misdemeanors that have accumulated over the course of the president’s almost two years in office, and whatever more may come to light through the special counsel’s investigation. Trump may have some success in convincing his most ardent followers that the payments represent a “private transaction” and that the Cohen case is nothing more than persecution by his political rivals. But if the range of lies and misconduct continues to develop in the special counsel’s inquiry, the campaign finance issue will at the very least find its way into the final accounting as part of a larger pattern of deception fully appropriate for an impeachment inquiry.