Don’t Use Shutdown Plans to Slash the Federal Workforce

The administration’s misguided attempt to lay off employees who aren’t excepted from shutdowns.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The first months of President Trump’s second term have been defined by firings of government workers, as the administration attempts to unilaterally strip the executive branch of many powerful assets. Elon Musk’s “DOGE,” along with agencies like the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), are choking off services to the public by incapacitating the agencies that are bound by law to deliver those services.

Currently, the administration is gearing up to further reduce agency capacity through reductions in force, or RIFs—this time targeted at those employees who do not work during a government shutdown. President Trump issued Executive Order 14210 on Feb. 11, directing agencies to use “efficiency improvements and attrition” to shrink the federal workforce. The order told agency heads to “promptly undertake preparations to initiate large-scale reductions in force (RIFs).”

It might seem like a quick and easy way to figure out whose jobs are important is to see who needs to work during a shutdown, call those people “essential,” and fire everyone else. But in truth, measures prepared for shutdowns have little to do with the kinds of considerations that go into RIFs. By seeking to combine two mismatched categories, the executive order misuses RIFs, misunderstands shutdown plans, and introduces political manipulation into what is meant to be an orderly process for winding down unneeded positions.

Nick Bednar provided an excellent primer on RIFs, including their historical context and use. The upshot is that RIFs are one of the federal government’s tools to lay off significant numbers of federal employees, but the government must provide an authorized reason for using them. Under OPM’s regulations, the government must demonstrate that it is conducting a RIF pursuant to a lack of work, a shortage of funds, a reorganization, or one of several other possible reasons. RIFs involve an orderly but elaborate process that is technical and arduous for all involved.

Trump’s order says that “[a]ll offices that perform functions not mandated by statute or other law shall be prioritized in the RIFs.” This language would, at first blush, seem to suggest a very narrow or perhaps nonexistent set of employees. After all, federal work is authorized by statutes and then paid for using appropriations made by Congress and signed into law. Congress re-ups those appropriations more or less every year, a functional blessing to the size and scope of the federal government. Despite a continual expansion of federal programs and discretionary funding, Paul Light and many others have pointed out that, while the number of government contractors has grown significantly, the size of the federal workforce has been flat since the 1950s. With this framing, the administration seems to be asserting that some significant number of agency staff are operating outside the law—an allegation that is as serious as it is unsubstantiated. The administration might not even be sure what it means at this point. Looking at how the administration has treated the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)—arguing that it could take the staff down to five (5) from 1,700 and then walking that back—suggests that their ideas about what staffing levels are needed to fulfill statutory agency functions is in flux, to put it mildly.

In any event, the order goes on to provide three categories of RIF-worthy employees. First are those who work on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives; employees with varying degrees of connection to DEI initiatives or activities have already been placed on leave while the government prepares to initiate a RIF. Second are people working in any units that the administration “suspends or closes”; the attempted closure of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is an example here. Third is anyone who does not typically work through a government shutdown, estimated to be 700,000 workers.

Agency plans for RIFs, including the third category, were due yesterday. As Bednar explains, when agencies prepare to RIF their employees, they must set the scope of a RIF in terms of competitive areas, which “must be defined solely in terms of the agency’s organizational unit(s) and geographical location.” This definition is one of the elements that will be scrutinized closely as the plans become available.

In a memo issued Feb. 26, OPM directed agencies to identify competitive areas including “positions not typically designated as essential during a lapse in appropriations.” That is government-speak for those positions that are not required to work during a government shutdown. The memo points agencies to the shutdown plans sent to OMB in 2019, some of which are archived from Trump’s first term.

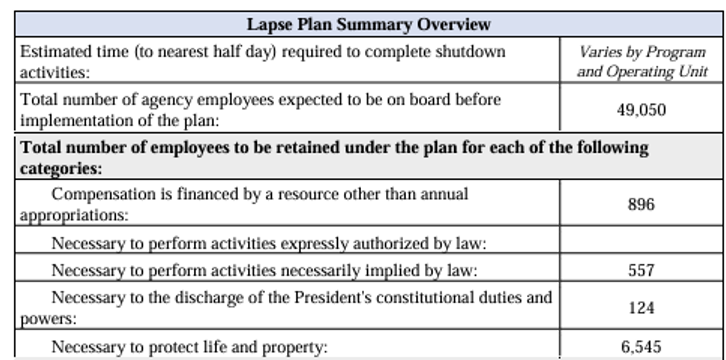

The plans begin by stating the number of agency employees and then working through different categories of different functions and activities that can continue even when the government runs out of appropriated funds. Here’s an example from the Department of Commerce in 2019:

The “excepted” categories include those functions that do not rely on annual appropriations bills, activities expressly authorized by law, activities necessarily implied by law, activities necessary to discharge the president’s constitutional duties and powers, and activities necessary to protect life and property. Different agencies’ staffs will fall into these categories differently. The Department of Justice, for example, had a higher share of its employees (for example, those working in the FBI) who conduct activities necessary to “protect life and property.”

But the categories used for RIF planning and those used for shutdown planning are apples and oranges. Unlike competitive areas as defined for RIFs, the shutdown plans do not hinge on organizational unit or geographic location but are focused instead on activities and functions. The most charitable reading of OPM’s guidance is that, when agencies are deciding which positions to RIF, they can take some guidance from which positions would have been excepted in a shutdown and go from there.

Colloquially, people in Washington, D.C., often refer to “essential employees” as those who work during a shutdown, as opposed to focusing on “excepted activities.” But it is not helpful to blend these two concepts together. An individual job can be made up of different amounts of excepted or non-excepted activities at any given time. Think of someone who spends 60 percent of their time working on a project that protects life and property and 40 percent of their time working on other tasks. That person would be “excepted” from a shutdown only for the 60 percent of their activities; it would be unlawful for them to work full time during a shutdown. Someone else might spend 100 percent of their time on excepted activities. It is incoherent, then, to tell agencies planning RIFs to look at which positions have previously been excepted from shutdowns, because even those whose positions were not 100 percent excepted might still fulfill some excepted functions.

It is easy to get lost in this fussy jargon, but when the executive branch runs out of appropriated funds, it mostly needs to stop working. Shutdown plans work through which functions can continue without an appropriation, but it is not always black and white. When the executive makes an overly expansive claim about what activities are excepted, agencies incur payroll and other expenses that Congress has not allowed. This implicates the separation of powers: Congress’s power of the purse is moot if the executive can spend whatever it thinks is important in the absence of an appropriation. Trump has experience pushing the limits of this ambiguity, however, which suggests that he will do so again if shutdown plans are used as the basis for RIFs.

In the 35-day shutdown during Trump’s first term, the administration relied on strained readings of the relevant statutes to except some unfunded but high-profile public-facing services like processing tax refunds and access to national parks, as well as some behind-the-scenes staff at unfunded agencies to work on issues related to the funded agencies. These choices not only directed those employees to perform work without timely payment but also exposed them to potential criminal sanction under the Antideficiency Act. In response, the U.S. Government Accountability Office took the unusual step of publicly rebuking the administration for calling some agency staff back to work.

In the shutdown context, the Trump administration made arguments that called workers in, but in the context of a RIF, it could take the opposite posture to maximize layoffs. This latter posture is part of what spooks some legislators about the looming government shutdown; will the president drag his feet or refuse to reopen the government if it shuts down?

But there’s a bigger reason that shutdown plans are a mismatch for agency RIF planning. When an agency prepares its contingency plan in advance of a potential shutdown, it does so at a particular moment in time, and with an eye to a temporary disruption in agency funding. The 35-day shutdown during Trump’s first term was the longest in history, but it, too, was temporary. That is very different from the kind of permanent restructuring that results from a RIF. What agencies are doing in their shutdown plans is deciding which functions fall into these different categories in the very near term, and only for a brief period. Those considerations might look very different if an agency had to plan for those jobs to be gone forever.

Shutdown plans are contingency plans, crafted to respond to short-term disruptions to federal funding. They cannot help determine which parts of government really matter. That is up to voters, working through Congress. The last big round of federal downsizing was a joint effort between President Clinton and Congress. Deliberative government takes time, but it ensures that large cuts and reorganizations happen as part of the democratic process, not unilaterally by an executive or his “tech support.” This time around, the executive is asserting that it knows what statutes require, and will cut accordingly. Will Congress acquiesce?

.jpg?sfvrsn=5a43131e_9)