Is Donald Trump's Tweet About Roger Stone Witness Tampering?

There's a good case that it is.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The president of the United States should spend more time reading Lawfare.

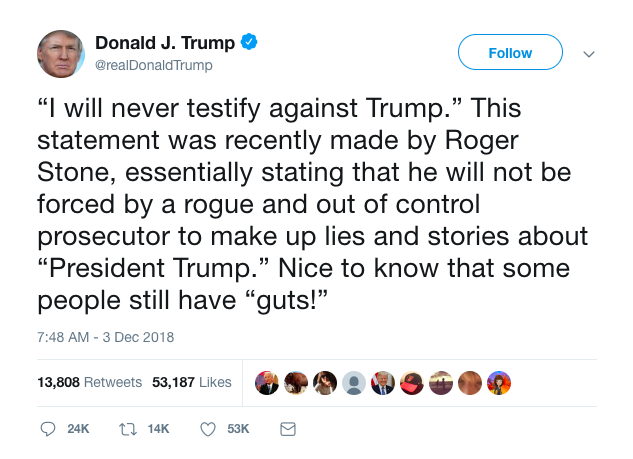

If he did, last August, he might have read the analysis we ran by Sarah Grant, Sabrina McCubbin, Yishai Schwartz and Benjamin Wittes regarding the potential applicability of federal witness tampering laws to the president’s public statements. And so he might have know why it was probably a bad idea this morning to tweet:

“I will never testify against Trump.” This statement was recently made by Roger Stone, essentially stating that he will not be forced by a rogue and out of control prosecutor to make up lies and stories about “President Trump.” Nice to know that some people still have “guts!”

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 3, 2018

The post back in August was responding to a remarkably similar tweet President Trump wrote regarding his former campaign chairman Paul Manafort:

I feel very badly for Paul Manafort and his wonderful family. “Justice” took a 12 year old tax case, among other things, applied tremendous pressure on him and, unlike Michael Cohen, he refused to “break” - make up stories in order to get a “deal.” Such respect for a brave man!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 22, 2018

As the group wrote then, Trump’s tweet about Cohen and Manafort raised serious questions under 18 U.S.C. § 1512(b)—better known as the statute criminalizing witness tampering. Under § 1512(b), it is illegal to “knowingly … corruptly persuade[] another person”—or to attempt to do so—“with intent to … influence, delay, or prevent the testimony of any person in an official proceeding” or “cause or induce any person to withhold testimony . . . from an official proceeding.” The authors concluded then that, while the specific Manafort tweet in question might not in and of itself constitute witness tampering, the tweet fit into a larger pattern of obstructive conduct by the president that could well fit that bill.

The same is true today of the president’s tweet about Roger Stone. In fact, insofar as the overall pattern of the president’s conduct toward the Mueller investigation might rise to the level of witness tampering, the fact that Trump is still tweeting out potentially obstructive messages in December—months after his initial August tweet—would seem to strengthen the case.

As our colleagues described in August, there is a split between the Third and Ninth Circuits and other federal circuits, including the Second and Eleventh Circuits, in how to understand “corrupt persuasion” under § 1512(b). Briefly, the Second and Eleventh Circuits take the view that an otherwise licit action—like persuading someone to invoke the Fifth Amendment right to remain silent—can constitute “corrupt persuasion” if it is done with an “improper purpose.” The Third and Ninth Circuits, on the other hand, have ruled that not only the intent animating the persuasion but also the means of the persuasion must be “corrupt.” In this understanding, bribery, for example, could be “corrupt persuasion,” but suggesting that a witness remain silent under the Fifth Amendment could not.

For this reason, a prosecutor would have a much easier time arguing for Trump’s August tweet praising Manafort as an example of witness tampering under the approach of the Second and Eleventh Circuits. The same is true of Trump’s Dec. 3 tweet on Roger Stone. The president’s lawyer Rudy Giuliani reportedly argued to a journalist in response to Trump’s Stone tweet that the message could not constitute obstruction “because the president is only encouraging someone not to lie”—and this is not a crazy argument, if that’s what Trump was really doing. However, prosecutors wouldn’t need to simply take Trump’s admonition that Stone and Manafort not “make up stories” at face value; telling someone to not “lie” and make incriminating statements has an altogether different meaning if incriminating facts exist and both parties know it. (The U.S. Courts of Appeals for the Third and Ninth Circuits agree that actually encouraging someone to provide false information to investigators would, indeed, constitute corrupt persuasion.)

Roger Stone has also weighed in, suggesting that:

ROGER STONE to me on todays presidential tweet: "Those who said the presidents warm and complementary tweet constitutes witness tampering should be reminded that I have never been contacted by any investigative body And therefore by definition this cannot be true" pic.twitter.com/E1tVgEOJhx

— Saagar Enjeti (@esaagar) December 3, 2018

Stone is wrong. Even if we believe his representations about having not been contacted, Stone is at an absolute minimum aware of the existence of grand jury proceedings—whether investigators have contacted him personally isn’t legally relevant here. Additionally, to the extent Stone wants to brush up on his legal research, legislative history suggests that Congress specifically wrote § 1512 so as not to include any particular standard for who constitutes a “witness”—in fact, the statute refers only to “another person” or “any person.” The Second Circuit has held explicitly that § 1512(b) covers potential witnesses—even those who, as the earlier Lawfare group wrote, “have neither previously cooperated with the government nor expressed any intention or desire to cooperate.” And judging by his comments to the press, this would certainly seem to describe Stone.

Still, calling Trump’s tweets witness tampering is far from a slam dunk. Any prosecutor actually pursuing these charges would need to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Trump specifically intended to intimidate witnesses or dissuade them from testifying against him through his tweets. And there are many more questions raised by the potential application of § 1512(b) to the president’s statements, including whether the statute could be implicated by a publicly posted tweet and whether Trump’s “encouraging someone not to lie” at some point becomes an implicit promise of a pardon if that person stays strong, a fact pattern that would bear a resemblance to the promise of financial reward that the even Third and Ninth Circuits understand as “corrupt.” Interested readers can take a look at the August Lawfare piece for more on those issues as well.

Our colleagues concluded their article by noting that “Mueller’s prosecutors would be foolish to focus on the president’s comments about Manafort as a stand-alone obstruction matter” but that those comments “could form part of a larger obstructive pattern—a part that exists outside of the exercise of core Article II presidential functions.” We agree with that assessment as a practical matter, but there is a risk here of missing the trees for the forest.

Yes, the president’s larger course of conduct is relevant to demonstrating his overall obstructive intent, and it helps smooth some of the edges of legal theories that don’t neatly apply to the exercise of Article II powers: examining a larger pattern of behavior means there's no need to get bogged down in the question of, for example, whether a president can obstruct justice by giving the FBI director an order that it is his constitutional prerogative to give. But wholly apart from the president's larger course of conduct, discrete violations of criminal statutes are important for a number of reasons. The principle way a president defends the “rule of law,” after all, is by actually following the law. We’d suggest that the president attempting to influence witnesses in the broad daylight of Twitter is as significant a breach of his constitutional duty as it would be if he were to secretly promise pardons in private—both are, in and of themselves, impeachable offenses.

True, the president may have also committed other offenses. But the seriousness of this individual transgression, even standing alone, should not be lost.

Recognizing where all the elements of a discrete statutory violation are present does have practical consequences, even outside a courtroom. While we’ve argued in the past, along with colleagues, that Congress could impeach the president for violating his oath of office even absent a direct violation of law, the fact is that it is extremely unlikely to do so. All three times the legislative branch has seriously considered articles of impeachment—against Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton—it has involved allegations of actual lawbreaking. And in the case of Nixon’s and Clinton’s impeachments, those allegations specifically concerned the obstruction of justice. Indeed, the articles of impeachment against those two presidents describe conduct that looks a lot like witness tampering.