e-Residency in Estonia, Part I: Wherein I Apply to Digitally Betray My Country

This week, I had the pleasure of hosting the third Hoover Book Soiree, which featured Edward Lucas of the Economist talking about his new book, Cyberphobia: Identity, Trust, Security, and the Internet. (We will podcast the discussion next week.) As a general matter, Lucas paints a bleak picture of our cybersecurity landscape, but he holds out one nation as an exception we all should emulate: the tiny Baltic country of Estonia.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

This week, I had the pleasure of hosting the third Hoover Book Soiree, which featured Edward Lucas of the Economist talking about his new book, Cyberphobia: Identity, Trust, Security, and the Internet. (We will podcast the discussion next week.) As a general matter, Lucas paints a bleak picture of our cybersecurity landscape, but he holds out one nation as an exception we all should emulate: the tiny Baltic country of Estonia.

Estonia is ahead of the curve in a lot of digital matters. Its president, Toomas Hendrick Ilves, is a genuine cybersecurity expert, a fabulous presence on Twitter (who has been disturbingly absent of late), and the only head of state who has ever been a guest on the Lawfare Podcast. As a general matter, the country is far ahead of the rest of the world in putting government services online.

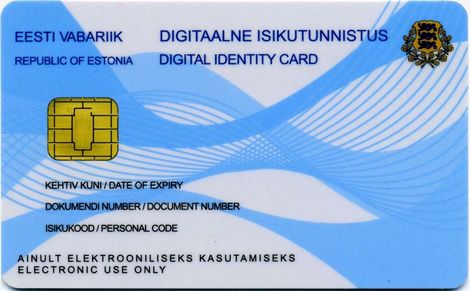

But Lucas focuses on Estonia because of a specific aspect of the country's cybersecurity policies: its government-issued digital identification card. "Unlike the citizens of any other country in the world, Estonians, through wise choices and good fortune, enjoy a combination of a secure, convenient digital identity, coupled with strong privacy protections and widespread public support," he writes.

The Estonian card is designed to allow people to verify their identities for purposes of signature, login, secure communications, and other interactions with government, companies and individuals. Instead of remembering countless passwords that can be compromised, you carry a card and remember a pair of PINs, one that allows the card to verify your identity, and one to authorize things. And here's the rub, as Lucas describes it: "Estonia is making its scheme available to foreigners. A law that came into force in 2014 allowed non-resident foreigners to apply for an Estonian ID card. They will have to meet the same standards, including providing biometric data (retina scan and fingerprints) as well as other supporting documents such as a passport. This can be done either during a visit to Estonia or—as from 2015—at an Estonian consulate abroad."

Yesterday, as a kind of cybersecurity practicum, and in a perhaps-shocking failure of digital patriotism, I applied to become an Estonian e-Resident.

I plan to blog the process as a way of exploring the values and pitfalls of Estonia's program. Is this all Lucas cracks it up to be? Or are there reasons to be skeptical of what Estonia is doing here? Is this system really providing security for Estonians and should other governments be doing similar? And in the absence of such actions by other governments, does it make sense for non-Estonians to let the nation of Estonia vouch for our identities?

Here's how Estonia describes its e-Residency program:

The Republic of Estonia is the first country to offer e-Residency — a transnational digital identity available to anyone in the world interested in administering a location-independent business online. e-Residency additionally enables secure and convenient digital services that facilitate credibility and trust online.

e-Residents can:

- Digitally sign documents and contracts

- Verify the authenticity of signed documents

- Encrypt and transmit documents securely

- Establish an Estonian company online within a day. At the moment a physical address in Estonia is required, which may be obtained using an external service provider.

- Administer the company from anywhere in the world.

- Conduct e-banking and remote money transfers. Establishing an Estonian bank account currently requires one in-person meeting at the bank, and is at the sole discretion of our banking partners.

- Access online payment service providers

- Declare Estonian taxes online. e-Residency does not automatically establish tax residency. To learn about taxation and to avoid double taxation please consult a tax professional.

All of these (and more) efficient and easy-to-use services have been available to Estonians for over a decade. By offering e-Residents the same services, Estonia is proudly pioneering the idea of a country without borders.

e-Residents receive a smart ID card which provides:

- digital identification and authentication to secure services

- digital signing of documents

- digital verification of document authenticity

- document encryption

Digital signatures and authentication are legally equivalent to handwritten signatures and face-to-face identification in Estonia and between partners upon agreement anywhere around the world. The e-Resident ID card and services are built on state-of-the-art technological solutions, including 2048-bit public key encryption. The smart ID card contains a microchip with two security certificates: one for authentication, called PIN1, and another for digital signing, called PIN2. PIN1 is a minimum 4-digit number for authorization, PIN2 is a minimum 5-digit number for digital signature.

In theory, this is an incredibly powerful instrument. If it—or something like it—were in wide usage, it could serve as everything from your login to social media and online banking to a means of verifying that the email from your mom complaining that she's stranded in Manila and really needs money actually comes from your mom and not from some scammer. Whether the Estonian scheme actually functions this way in practice, however, depends on a bunch of questions:

- How secure is it really? Have the encryption and the algorithms associated with the card been tested rigorously and by whom? How easily could it be compromised and how severe would the consequences of a compromise be? (I would love to hear from our technical cybersecurity folks on this question)

- Do people trust it? The greatest security systems in the world are worthless if they are not deployed and used, after all. How widespread is the use of this system in Estonia, for what functions, and by whom?

- What do we know about the rates of cybercrime, identity theft and data breaches in Estonia as opposed to elsewhere in the world?

- Will non-Estonians trust an identity-verification mechanism sponsored by a government not their own. The idea is certainly not crazy. Lots of people trust Switzerland to protect their money, after all. Why not Estonia to protect and verify their digital identities? But the idea is also not, shall we say, immediately intuitive. It is fair to ask: Why should one's own government not be responsible for verifying one's online identity? It would be odd for Estonia to issue my passport. Why should it issue my digital passport?

- Do people really want a verifiable online identity at all? I know I do. I think the lack of reliable identity verification is at the core of many cybersecurity problems. But the culture of the internet is one that puts a premium on anonymity and generally disfavors accountability of any kind. In such a climate, can any voluntary system of identity verification really catch on?

The Estonian card seems like a great vehicle through which to look at these questions.

The application process, which I began yesterday online, was quite easy. I provided some basic information about myself (name, address, phone number, email, citizenship), a copy of my driver's license, and a photo, and I forked over 50 euros. I quickly received the following email in response, subject lined "Your e-Residency application has been received":

Dear applicant,

Thank you for applying for e-Residency. Your application has been submitted and will be reviewed shortly. You will be notified when the application review process begins. If your application is approved, your e-Resident smart ID-card will be sent to your chosen location. The whole process will take about a month. However, as e-Residency is in the beta stage and the number of applications is currently greater than anticipated, we highly appreciate your patience. The Estonian Police and Border Guard Board will keep you informed about the application process by sending progress reports to the e-mail address you provided in the application.

For additional questions please see: e-resident.gov.ee or e-mail e-resident@gov.ee

Yours Truly,

Kaspar Korjus

e-Residency Program Director

So now I wait and do research on the Estonian program. I will keep readers posted as my application progresses. If the embassy here in Washington permits it, I will film or record my entire in-person interaction for posting to the site. I will also tweet this post at President Ilves, who undoubtedly has thoughts on the subject. And I am very interested in hearing from readers about the various questions this program raises.

In particular, I am interested in hearing from Estonians and others who have the card about what use they make of their digital identifications, what problems they have had with it, and what advantages it offers. And I'm interested in hearing about the technology that underlies it. Does a system like Estonia's add real security or does it create a dangerous security monoculture dependent on the integrity of a single technology. Or does it, perhaps, do both?

UPDATE: I received an email from Katre Kasmel of the e-Residency team who informs me (a) that "we do not ask for applicants’ retina scan, only fingerprints are taken at the moment," and (b) that "a copy of your passport or ID-card (i.e travel document) is asked for during the application process, a copy of driver's license is not enough." As a result, "the Estonian Police and Border Guard Board will write to you during the review of your application and ask for a photo of your passport."