Emergencies Without End: A Primer on Federal States of Emergency

The United States is in a state of emergency: 28 national ones and many more local. This might come as a surprise, but it isn’t new—this month marks the start of our 39th year in a continuous emergency state. What is an emergency, and how did we get here? This post explains.

Background

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The United States is in a state of emergency: 28 national ones and many more local. This might come as a surprise, but it isn’t new—this month marks the start of our 39th year in a continuous emergency state. What is an emergency, and how did we get here? This post explains.

Background

All presidential authority is derived from either the Constitution or an act of Congress. As our Constitution contains no general emergency powers provision, presidents must look to Congressional acts for the authority to act beyond the normal limits of their powers. By 1973, Congress had enacted over 470 statutes granting the president special powers in times of crisis. These powers would lay dormant until the president declared a state of emergency, at which point all would become available for his use. And at the time, the president could declare an emergency as he alone saw fit: no procedures or rules constrained his discretion.

On Dec. 16, 1950, President Harry S. Truman declared a state of emergency in response to Korean hostilities. But the emergency didn't end with the war. By 1972, it was still in effect (and being used to wage war in Vietnam), so the U.S. Senate convened a special committee to investigate. The committee discovered three other active emergencies, each of which independently gave the president access to the entire set of emergency powers. According to the committee’s 1973 report, the crisis provisions together “confer[red] enough authority to rule the country without reference to normal constitutional process.”

In 1976, Congress attempted to pull back the president’s emergency powers by enacting the National Emergencies Act. First, the act revoked (two years after its enactment) any powers granted to the president under the four states of emergency still active at the time. Next, it prescribed procedures for invoking these powers in the future. No longer can a president give force to the hundreds of emergency provisions by mere proclamation. Instead, he must specifically declare a national emergency in accordance with the act and identify the statutory basis for each emergency power he intends to use. Each state of emergency is to end automatically one year after its declaration, unless the president publishes a notice of renewal in the Federal Register within 90 days of the termination date and notifies Congress of the renewal. Finally, the act requires that each house of Congress meet every six months to consider a vote to end the state of emergency.

Not once has Congress met to consider such a vote. It is not exactly clear why. But the provision would have lost much of its intended force even had Congress complied: It originally allowed Congress to end an emergency by concurrent resolution (that is, if majorities in both houses voted to end it). But in 1983, the Supreme Court declared this sort of legislative veto over presidential action unconstitutional. A 1985 amendment to the act now requires a joint resolution to end the emergency, meaning that any Congressional vote to end the emergency is subject to the president’s veto, which may be overridden only by two-thirds majorities of both houses.

National Emergencies Today

The National Emergencies Act was only partially successful. Presidents declaring national emergencies now do so pursuant to the act, and they do indeed specify the emergency powers they intend to use. (President George W. Bush’s Sept. 14, 2001 emergency proclamation, for example, identified nine.) But insofar as the act was intended to put a stop to the perpetual emergency state, it failed. Not only does Congress not meet to consider invalidation votes, but presidents routinely renew the emergencies, sidestepping the automatic termination provision.

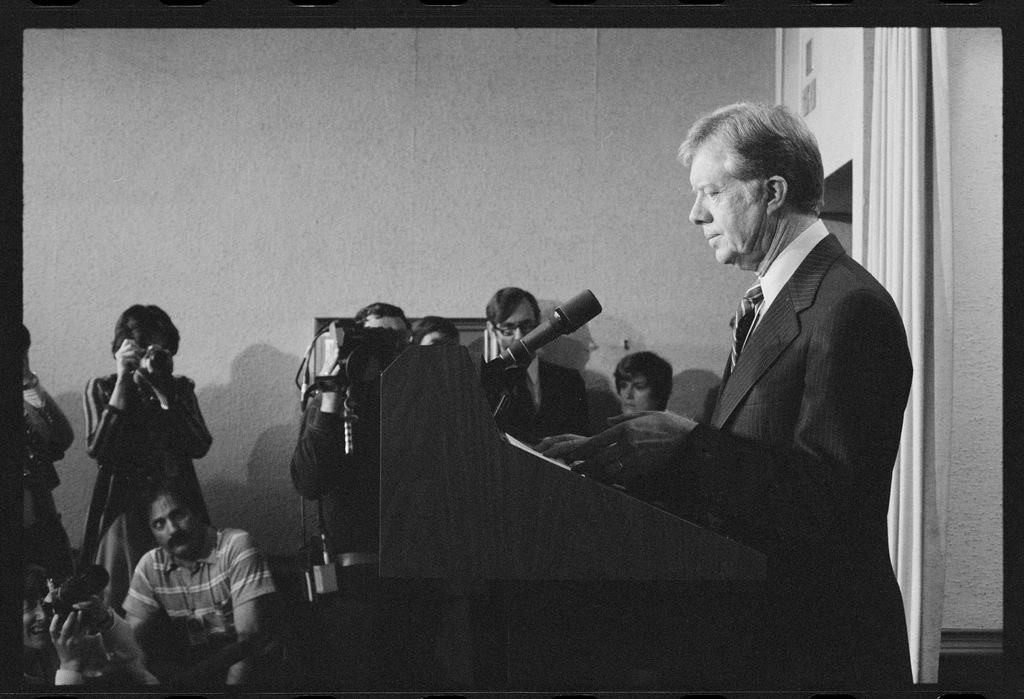

As of today, 28 emergencies remain in effect. The list still includes the first emergency authorized under the act—President Jimmy Carter’s 1979 emergency, declared ten days after Iranian students took American diplomats hostage in Tehran. Earlier this month, President Donald Trump renewed the emergency for the 38th time.

Why have seven presidents extended the 1979 emergency 38 times? It, along with a second emergency declared in 1995 to implement the oil embargo, forms the basis for many of the United States’ sanctions on Iran. The president’s (and thereby the the Treasury Department’s) power to impose sanctions for foreign policy purposes comes from the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). IEEPA was passed one year after the National Emergencies Act, and it grants the president sweeping economic power in response to “any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.” But IEEPA doesn’t supplant the National Emergencies Act. Rather, the president may take advantage of IEEPA powers only if he declares a national emergency (with respect to that foreign threat) under the National Emergencies Act.

In fact, 26 of the 28 national emergencies currently active invoke IEEPA. The remaining two also exist to respond to foreign threats. The first is President Bill Clinton’s 1996 emergency, declared after the Cuban military shot down two civilian airplanes off of the Cuban coast. It allows for the regulation of vessels in U.S. waters that may enter Cuban territorial waters “and thereby threaten a disturbance of international relations.” The second is Bush’s Sept. 14, 2001 emergency. It gave the president broad powers to mobilize the military in the days (and now years) after the attacks. But nine days later, Bush issued a second emergency proclamation, this time invoking IEEPA explicitly for the purpose of restricting terrorist financing.

If every active national emergency was declared in response to foreign threats, what of domestic ones? No law prevents the president from declaring a national emergency in response to a domestic crisis: Bush did in response to Hurricane Katrina. (The declaration itself omits reference to the National Emergencies Act, but a later proclamation cites the act for authority to end the emergency.) President Barack Obama also did so in response to the Swine Flu epidemic. Still, it isn’t very common. Instead, two other acts govern emergency responses to local disasters and public health emergencies: The Stafford Act and the Public Health Services Act.

The Stafford Act

The federal government uses the Stafford Act of 1988 to respond to disasters that are less than national in scope but still call for federal relief. The act authorizes the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to coordinate with and deliver aid to state or local governments overwhelmed by disasters or emergencies. It works according to a two-step process.

First, a state governor must find that the disaster or emergency is “of such severity and magnitude that effective response is beyond the capabilities of the State and affected local governments.” (The chief executives of D.C. and of any American commonwealths or territories count as state governors here.) Second, the governor must request a presidential declaration that a disaster or emergency exists. This request must be accompanied by a showing that the state has implemented its own emergency plan. If the president determines that “primary responsibility for response rests with the United States,” he may sidestep these two steps and make the emergency or disaster declaration on his own .

Once made, the presidential declaration opens the door to coordinated FEMA assistance and money from FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund. FEMA and the state will negotiate a FEMA-State Agreement, which describes the disaster, the types of assistance that FEMA will provide and any conditions on the assistance. There are two types of declarations: “major disasters” and “emergencies.” The first category covers natural or manmade disasters (like hurricanes, earthquakes, or explosions). Emergencies cover “any other occasion[s] or instance[s]” where federal funds are needed to “save lives and protect property, public health, and safety, or to lessen . . . the threat of a catastrophe.” The major difference between the two is that emergencies are subject to a $5 million cap on federal assistance, while disasters are not (§ 503). (A president can override that cap if necessary, but he must report the decision to Congress.)

As of today, Trump has made 128 Stafford Act declarations, including ones for hurricane relief in Puerto Rico, Texas, Alabama, and Florida.

Public Health Emergencies

Section 318 of the Public Health Service Act, enacted in 1944, authorizes a third type of emergency declaration. It allows the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (instead of the president) to determine that a public health emergency exists. The determination can be on the basis of 1) a disease or disorder that presents a public health emergency, or (2) a public health emergency, which includes “significant outbreaks of infectious diseases or bioterrorist attacks.”

The secretary may then respond with funds from the Public Health Emergency Fund, though the fund may contain as little as $57,000. The secretary may also reassign public health personnel to the affected area and investigate into the “cause, treatment, or prevention” of the disease or disorder. Unlike the Stafford Act provisions, the Public Health Service Act does not require any preceding state action or requests—these emergencies need not be confined to one specific state. The public health emergency lasts for a renewable 90-day period.

In late October, Trump directed the acting health and human services secretary, Eric Hargan, to declare the opioid epidemic a nationwide public health emergency. The president was repeatedly criticized for using this type of emergency (as opposed to a National Emergencies Act emergency or a Stafford Act emergency) to address the crisis. But there is precedent for converting one type of emergency to another: the Obama administration declared the swine flu epidemic to be a public health emergency and renewed that declaration twice before also declaring it to be a national emergency under the National Emergencies Act.

Will these emergencies last forever? Not necessarily. Presidents let some emergencies (like those for the swine flu) expire, and they end others by proclamation. Congress, too, may try to end any national emergency (over presidential veto) at any time. But if the last four decades are any indication, some emergencies are here to stay.

.png?sfvrsn=bd249d6d_5)