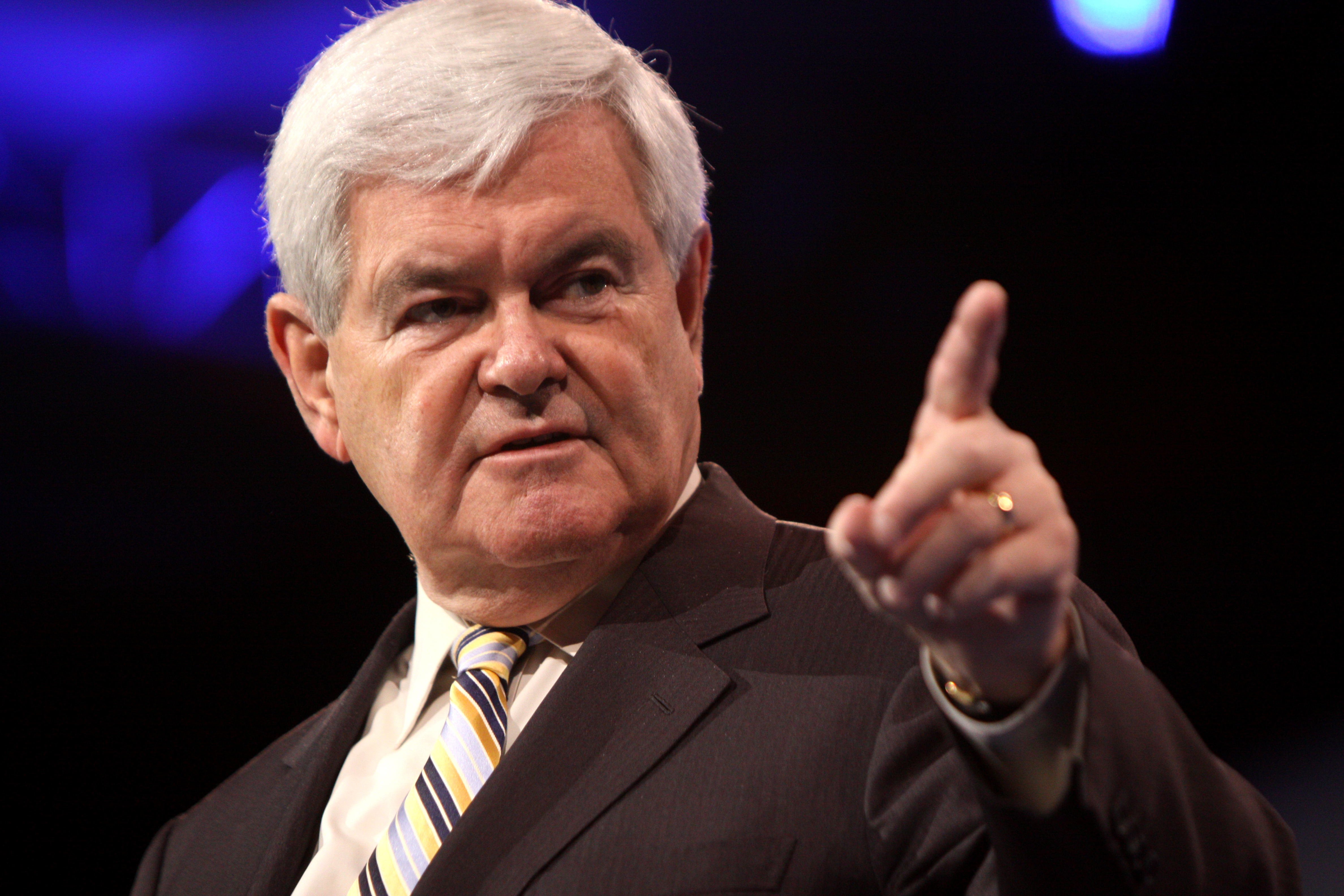

Even Newt Gingrich Has to Testify in Fulton County

While you were recovering from election night, the former House speaker and I were in court.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

It is a chilly Wednesday morning, the day after the midterm elections that will shape the next two years of American politics, and I am waiting for an elevator at a courthouse in Fairfax, Virginia, making small talk with Newt Gingrich.

Like the rest of the nation, I would prefer to spend the day after election night on my couch, doom-scrolling on Twitter as I nurse a hangover from too much whiskey and cable TV coverage of the election results. But instead, I am in Virginia, pestering the former speaker of the House—who would presumably also rather be home licking his election night wounds—with questions that he won’t answer.

“How do you feel about the hearing today?” I ask him as he stares down the hallway past my shoulder, where his attorneys, John Burlingame and Randy Evans, disappeared a few minutes ago to check on the courtroom assignment.

He stares blankly at me in response, as if I didn’t say anything at all.

The most I can get this famously chatty man to tell me is that he, too, stayed up late watching TV coverage of the midterm results.

It is fitting that Gingrich is not in the mood to answer questions this morning. He is here, as I am, for a hearing to decide if he should be compelled to answer questions from the Fulton County, Georgia, special purpose grand jury investigating Donald Trump’s 2020 election meddling in the state. While Gingrich has not been designated a target of the investigation, at least not yet, the special purpose grand jury’s interest in his testimony appears to focus on his communications with the Trump campaign about television advertisements that espoused false claims about election fraud in Georgia and other states.

As you might recall from Mark Meadows’s similar out-of-state witness hearing in South Carolina last month, the matter is being litigated in Virginia because that’s where Gingrich resides. While a state’s authority to subpoena a witness generally ends at its borders, every state has adopted some variation of the Uniform Act to Secure the Attendance of Witnesses From Without a State in Criminal Proceedings, which sets out a cooperative procedure to compel the testimony of out-of-state witnesses.

The applicable Virginia law, VA Code § 19.2-274, provides that a witness who resides in the state can be compelled to testify in an out-of-state criminal proceeding if a local judge issues a summons directing him or her to do so. The statute requires the local judge to find that the witness is both “material” and “necessary” to the out-of-state grand jury’s investigation, and that a summons to appear in another state will not cause “undue hardship” to the witness.

Now, in Courtroom 5E, having spurned my efforts to engage him in conversation in the elevator, Gingrich sits on the front pew in the gallery, looking bored. I suspect he looks bored, and I am bored too, because it’s well past the scheduled 10:00 a.m. start time.

The presiding judge in the case, Robert Smith, has a full docket of criminal motions to get through today. So, the former speaker of the House has to wait his turn as the judge hears a spate of bond motions and plea agreements.

Finally, a few minutes past 11:00 a.m., Judge Smith decides that he will hear argument from Gingrich.

“You’re up,” he barks at Burlingame. At this, Gingrich and his legal team rise from their seats in the gallery and make their way toward a table on the left side of the courtroom.

Meanwhile, a Virginia prosecutor, Chaim Mandelbaum, sidles up to the lectern to provide his summation of the issues on behalf of the Commonwealth and the Fulton County District Attorney’s Office.

Mandelbaum begins by contending that the requirements for compelling Gingrich’s testimony under the law have been met. He points out that the Fulton County special purpose grand jury’s supervising judge, Robert McBurney, issued a “material witness certificate” certifying that Gingrich is a “material” and “necessary” witness in the investigation. Additionally, Mandelbaum claims, Gingrich’s travel to Atlanta would not cause him “undue hardship,” because the State of Georgia would provide him with travel and accommodation. “Your Honor, we would ask that the court issue such an order,” he finishes.

Following Mandelbaum’s perfunctory opening statements, Burlingame strides to the lectern on behalf of Gingrich. He announces that the court should not order Gingrich to testify in Georgia for two “core” reasons. He argues, first, that prosecutors cannot use the Uniform Act to compel Gingrich’s testimony because the law does not apply to the type of grand jury impaneled in the Fulton County investigation—that is, a “special purpose grand jury.” Further, he claims, Gingrich cannot be forced to appear in Georgia under the Uniform Act because his testimony is not “necessary.”

Expounding on the first argument, Burlingame looks to the text of Virginia’s statute. He explains that two types of proceedings trigger application of the Uniform Act: a pending “criminal prosecution” in another state, or a “grand jury investigation” that has commenced or is about to commence out of state.

As to the first “trigger,” Burlingame notes that there is no “pending criminal prosecution” in relation to the Georgia election probe. As to the second, he contends that the Fulton special purpose grand jury is not a “grand jury” as contemplated by the statute. Unlike a traditional grand jury, he observes, a special purpose grand jury is not authorized to issue indictments. “The best they can do is issue a report,” he says.

To bolster this argument, Burlingame points to a recent Texas Court of Criminal Appeals decision. In that case, Dallas-based lawyer and podcast host Jacki Pick Deason fought off her own subpoena to testify in Fulton County. She argued that the special purpose grand jury’s investigation is a civil inquiry, not a criminal inquiry. As such, she claimed, Georgia prosecutors lack authority to compel her testimony under the Uniform Act, which applies only to criminal proceedings. While the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ultimately quashed Deason’s subpoena on other grounds, a majority of the court’s nine elected judges indicated that they would be receptive to the idea that the act does not apply to Georgia’s special purpose grand jury proceedings.

Now, directing the court’s attention to the Texas case, Burlingame observes that the justices “voiced real concern over whether this variant of Georgia special purpose grand jury was a ‘grand jury’ for the purposes of the Uniform Act.”

Then Burlingame turns to the legislative history of the Uniform Act, which the Commonwealth adopted in the 1950s. He stresses that Georgia did not adopt its special purpose grand jury statute until many years later, in 1974. “When the Commonwealth adopted the Uniform Act, it could not have contemplated that over two decades later Georgia was going to create this sui generis entity—the Georgia special purpose grand jury,” he declares.

Next, Burlingame pivots to his second argument: The Commonwealth cannot show that Gingrich’s testimony in Georgia is “necessary” as required under the applicable Virginia law.

“The timeline is important here, Your Honor,” Burlingame stresses. He explains that Gingrich received a Sept. 1 letter from the House Select Committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. The letter invited Gingrich to appear before the committee for an interview about his efforts to advise the Trump campaign on advertisements that pushed false claims about election fraud during the 2020 election. After that letter was made public, Burlingame continues, the Fulton County district attorney sought Gingrich’s testimony in the Georgia investigation based on information in the Jan. 6 committee letter.

Having set out this all-important timeline, Burlingame complains that the Fulton County district attorney wants to question Gingrich about topics that are “coextensive” with those set out in the Jan. 6 committee letter. He notes that Gingrich has agreed to appear before the House select committee on Nov. 21 and will “address all of the topics listed in the Sept. 1 letter.” For that reason, Burlingame declares, “it’s not necessary for Speaker Gingrich to have to travel to Georgia to address the exact same topics.”

Burlingame notes that the Jan. 6 committee intends to release its public report in December, which will include a transcript of its interview with Gingrich. “At a minimum,” he urges, Judge Smith should wait to issue a ruling on this matter until after the committee releases its public report. The court can always revisit the issue after the Fulton County district attorney receives and evaluates the transcript of Gingrich’s testimony, he says.

Continuing this line of argument, Burlingame stresses that Tim Heaphy, the chief counsel for the Jan. 6 committee, will ensure that the committee’s interview with Gingrich is thorough. “It almost sounds like the Fulton District Attorney is concerned that the professional attorneys for the Select Committee aren’t going to be doing a capable job,” he snipes. “Your honor, I assure you they will.”

As Burlingame paces back to his seat, Mandelbaum pops up to respond on behalf of the Commonwealth. Addressing Burlingame’s necessity argument, he notes that the Jan. 6 committee and the Fulton County special purpose grand jury are carrying out distinct investigations. Because the Fulton County investigation involves a focus on criminal violations of Georgia law, the grand jury is likely to have questions that differ from the Jan. 6 committee’s inquiries.

Then Mandelbaum turns to the question of whether the Uniform Act applies in the context of a special purpose grand jury. He asserts that the Fulton grand jury is “unquestionably” a criminal grand jury within the meaning of the act. For support, Mandelbaum proffers a decision from the special purpose grand jury’s supervising judge, McBurney, in which he found that the special purpose grand jury is conducting a criminal investigation.

After Burlingame reiterates several points in response, Smith is ready to issue a ruling. The Uniform Act “doesn’t make a distinction between something like a special grand jury or regular grand jury,” he says. “I think this falls under the statute, so the summons will issue.”

At this, Burlingame leaps back up. Stressing that he “respects the court’s decision,” he asks the court to stay the summons to testify until Gingrich can seek an appeal of the decision.

“I’m not going to do that,” Smith responds. “I’m going to sign it now and get things going.”

After the parties spend several minutes preparing the order for the summons, Smith adjourns the hearing. Gingrich walks out of court, flanked by his lawyers and a police escort.