Exceptional Access: The Devil is in the Details

Author’s note: Despite appearing under my byline, this post actually represents the work of a larger group. The “Keys Under Doormats: Mandating Insecurity” group includes Harold Abelson, Ross Anderson, Steven M.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

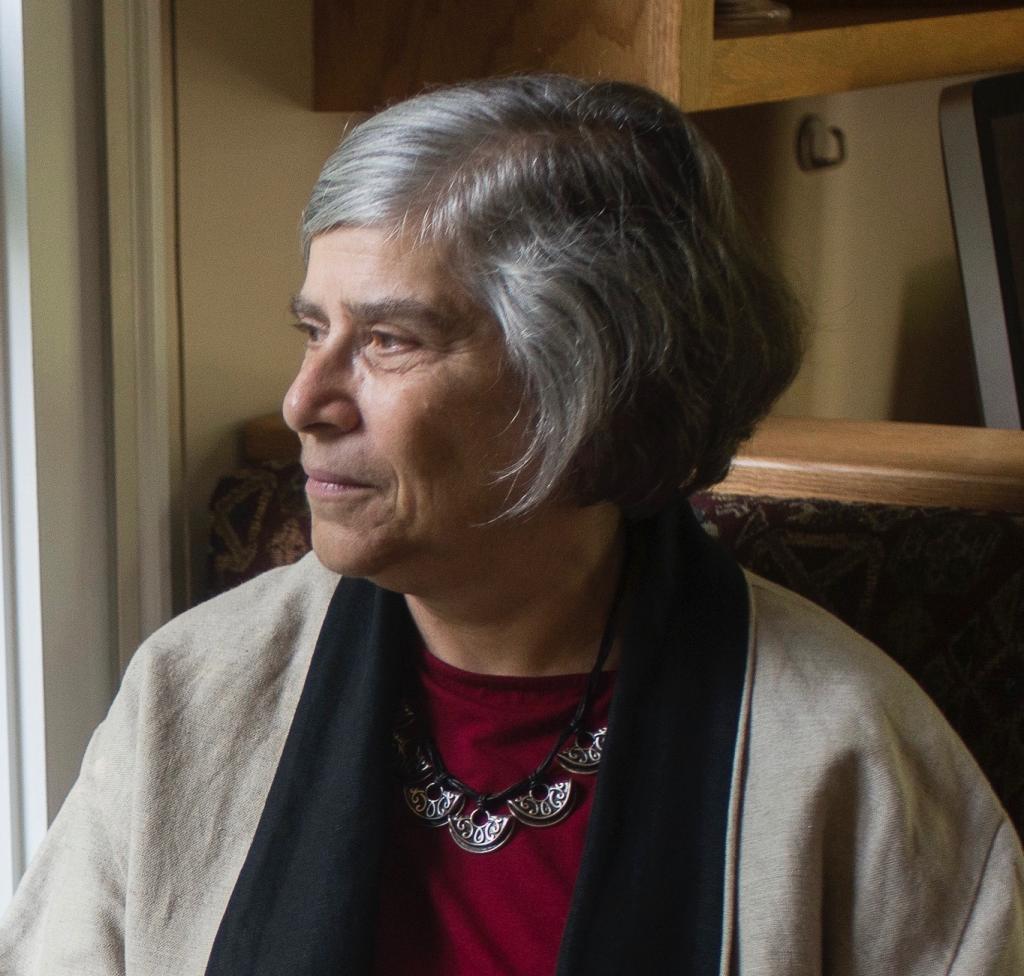

Author’s note: Despite appearing under my byline, this post actually represents the work of a larger group. The “Keys Under Doormats: Mandating Insecurity” group includes Harold Abelson, Ross Anderson, Steven M. Bellovin, Josh Benaloh, Matt Blaze, Whitfield Diffie, John Gilmore, Matthew Green, Susan Landau, Peter G. Neumann, Ronald L. Rivest, Jeffrey I. Schiller, Bruce Schneier, Michael A. Specter, and Daniel J.Weitzner, who jointly authored the report last year.

In August, Matt Tait reported in Lawfare on Apple's announcement of a system (Cloud Key Vault) that lets iPhone users store information on Apple servers, protected by a Hardware Security Module (HSM) in such a way that no one besides the user can gain access (not even Apple itself). According to Tait, that reopens the "going dark" debate over giving law enforcement exceptional access to stored information; he claims that it circumvents many of the objections raised by the security and privacy communities. As authors of a report, Keys Under Doormats, which studied the vulnerabilities of exceptional access systems, we commented earlier on Lawfare that Cloud Key Vault does not actually provide exceptional access.

Tait has now replied by suggesting that a modification of Apple’s system could do so. His suggestion is that the phone would contain a packet of information enabling decryption of its contents at Apple. Tait has proposed a new special device (the “AKV vault”) to handle this decryption function. When law enforcement obtains an encrypted phone, it would extract the information packet and take it to Apple for decryption.

One of the important features of Apple’s original proposal is that only the end-user can use it to recover her device. It's thus of limited value to law enforcement or hackers. But turn this CKV into Tait’s AKV, and it immediately becomes a target. The AKV can instantly break any device to which you have physical access. State level actors can be expected to coerce an AKV technician to obtain such a prize. What’s more, once an AKV has been built, a government can coerce Apple to hand one over and use it to break phones in their possession, or break into it to extract the master keys. And history shows that the security provided by HSMs is rarely perfect.

This leads to the issue of jurisdiction. If the AKV is located in the United States, does that mean that only the U.S. Government gets access to any device while the government of China will not? Will China insist that devices sold in China use an AKV in China?

These arguments should sound familiar, as they are some of the arguments we have been making all along. Apple’s CKV is certainly an interesting development, but because it doesn’t provide exceptional access, it doesn’t have the hard problems around jurisdiction and control. But introduce exceptional access, that pesky “back door” and the problems come back. The fundamental issues have not changed.

With security architectures, the devil is in the details. We encourage Tait and others to explore his suggestion to specify an exceptional access architecture in enough detail to be rigorously evaluated by the security community.

.jpeg?sfvrsn=f6228483_10)