A Few Words in Defense of Resignation

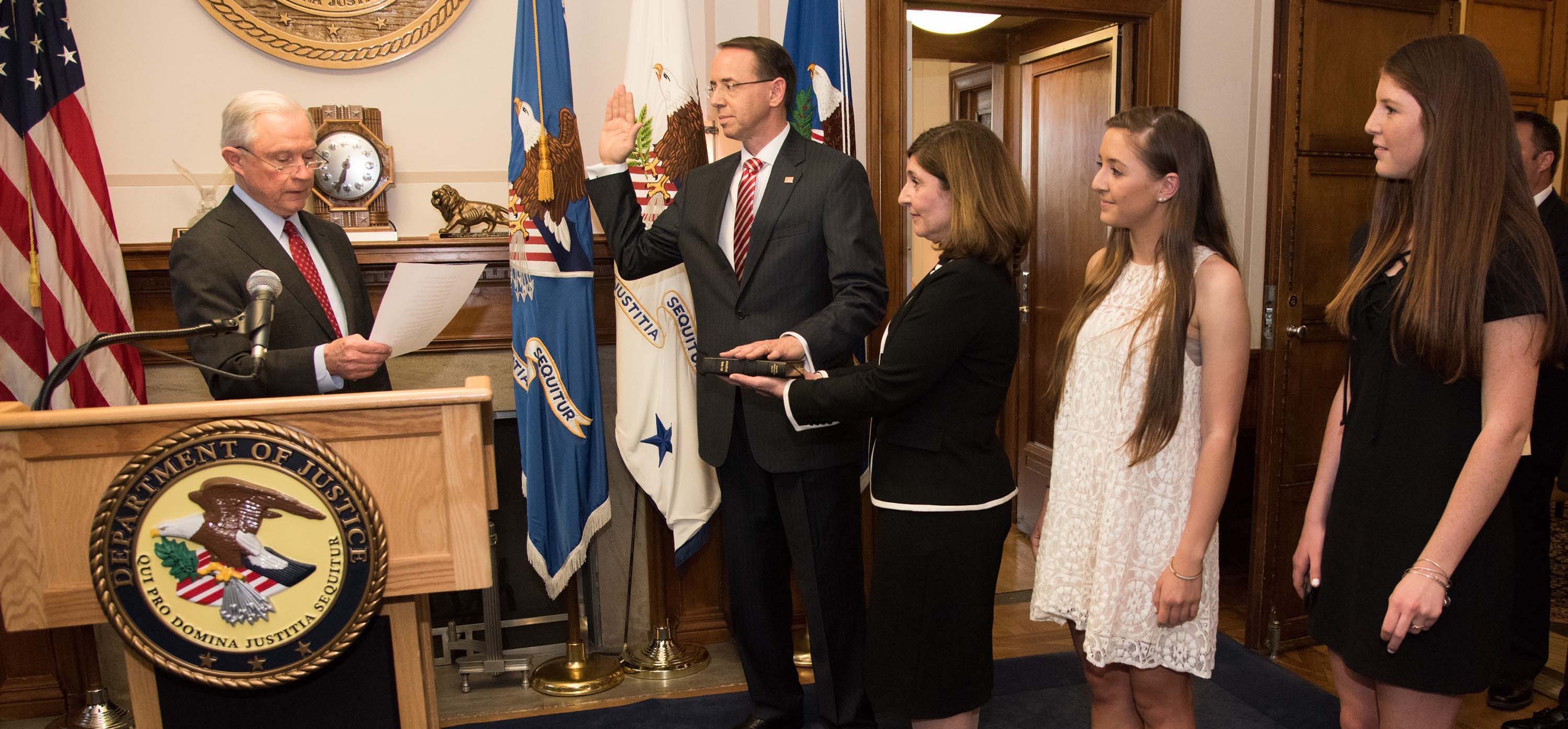

Last week, after the President took the opportunity of an interview with the New York Times to attack the Department of Justice’s leadership, I suggested that Attorney General Jeff Sessions and Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein should jointly resign.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Last week, after the President took the opportunity of an interview with the New York Times to attack the Department of Justice’s leadership, I suggested that Attorney General Jeff Sessions and Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein should jointly resign. Sessions and Rosenstein, I argued, should step down “together [issuing] a strong statement in defense of the integrity of federal law enforcement, the men and women who carry it out, and the processes under which they work.”

Responding over the next two days, Jack Goldsmith argued that while “one or both men would be justified in resigning” given the president’s public vote of no confidence, “the resignation of the top two officials in DOJ would throw DOJ into more of a crisis than it already is in.” In his view—their role in Comey’s firing aside—Sessions and Rosenstein’s service has so far protected the Justice Department’s “independence and integrity at a time when those things are under attack by the President.” And the independence of federal law enforcement, he argued, is best protected “by maintaining independence in practice” through honorable service, rather than through resignation.

Jack returned to the question of resignations yesterday. “The only thing for the men and women of the Justice Department to do,” he wrote, “is to keep doing their jobs well until they get fired. That is the way to serve the American people in upholding the rule of law in the face of a president bent on trying to destroy it.”

What Jack has said publicly, a number of other people have also urged on me privately. If Sessions and Rosenstein were to walk away tomorrow, they would leave a vacuum at the top of the Justice Department that Trump would be free to fill or exploit. Associate Attorney General Rachel Brand would become acting attorney general, but she wouldn’t be in a materially different position from either Sessions or Rosenstein with respect to a president who has no apparent regard for the independence of law enforcement. The President would also be free to name a new attorney general and deputy attorney general more to his choosing—perhaps people who, assuming he could get them confirmed, would either pressure or remove Robert Mueller at the president’s will. As Jack put it, it’s perfectly possible that “resignations in protest of Sessions' departure would only make matters worse.”

The attacks from the president have continued. On Monday and Tuesday morning, he took to Twitter to further air his grievances against the Justice Department—and against his attorney general in particular. Trump described Sessions as “beleaguered” and demanded twice that he investigate Hillary Clinton and her campaign. He declared that the attorney general has “taken a VERY weak position on Hillary Clinton crimes” and on the leaking of classified information. To polish things off, he also took a shot at Acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe.

Trump reiterated his dismay over Sessions’ decision to recuse himself from the Russia investigation and his failure to be “tougher” on “the leaks from the intelligence agencies” in remarks in the White House Rose Garden on Tuesday, but he held back from outright calling for his resignation. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal the same afternoon, he downplayed Sessions’s early endorsement of his candidacy and declared himself “very disappointed in Jeff Sessions.” Of potentially removing the attorney general from office, he said: “I’m just looking at it.”

So far, anyway, Sessions and Rosenstein are both following Jack’s advice, not mine. ABC News reports that Sessions has “no plans” to resign, and allies of the attorney general have said that “he’s not going anywhere.” Speaking at the NAACP’s annual convention, meanwhile, Rosenstein held back from criticizing the president, choosing to cite his inaugural address approvingly instead.

I have been thinking since I wrote my initial piece about the question that Jack raises: Why is resignation better than staying in place and doing the job independently in practice while taking the president’s verbal slings and arrows? Shouldn’t we demand of Sessions and Rosenstein that they man the ship honorably until the day they are given an improper order—or until the day Trump fires them? Shouldn’t we demand that Rosenstein remain in place to protect Mueller’s investigation—for which Trump blames him? And shouldn’t we prefer that Sessions remain in place so that Trump cannot replace him with a loyalist who is not recused and can, as the President apparently wishes, use his office to stymie Mueller’s efforts?

The short answer to these questions is that I’m not certain that resignation is the right course—in other words, that I have charted the better course than Jack has. There are, indeed, real dangers to resignation.

But I also think it is worth considering the real dangers of law enforcement leadership’s remaining in place in situations like this.

Let me confess at the outset that part of my reaction in favor of resignation was driven by an emotional response: the grotesque offense to the personal dignity of Sessions and Rosenstein that the President has given over the past week. Whatever one thinks of the conduct of either man—and I have certainly been critical—they are human beings, and the President of the United States, at whose pleasure they serve, is telling lies about them in public and through them about the men and women who serve under them. This emotional response was undoubtedly on display when I wrote after the Times interview that "If Attorney General Jeff Sessions does not resign this morning, it will reflect nothing more or less than a lack of self respect on his part—a willingness to hold office even with the overt disdain of the President of the United States, at whose pleasure he serves, nakedly on the record." If my boss ever did that to me, even if he or she were not the President and I were not a cabinet secretary, wild horses couldn't make me show up for work the next day. But I acknowledge that the unwillingness to suffer such public humiliation might actually be a sign of weakness on my part—that Sessions and Rosenstein here may be attempting something honorable by tolerating more than I would to protect people beneath them.

The trouble is that remaining in office does not merely demean the individual dignity of the attorney general and the deputy attorney general when the President whines about the attorney general’s compliance with Justice Department recusal rules; when he attacks the attorney general for not investigating a political opponent; when he openly suggests that the Justice Department’s leadership should act in his personal interests; or when he suggests that the deputy attorney general is biased against him as a result of previous service as U.S. attorney in a Democratic-majority city. These are also degradations of the institutional offices these men hold. And continuing to hold those offices in silence when the president says these things them permits that degradation to go unchallenged—both before the workforce and before the public.

To the workforce, this sort of rope-a-doping by the department’s leadership might provide a short-term protection against political interference in an investigation, and I don’t diminish the importance of that protection. Rosenstein and Sessions (who is recused, in any event) may by tolerating belittling by the President to allow their investigators and prosecutors to do their work unmolested. But the long-term cost is the corrosion of the norm not merely that investigators and prosecutors are ultimately protected from White House interference on investigative matters, but that presidential attempts at such interference are themselves unacceptable. To allow the Justice Department and FBI workforces to witness on an ongoing basis the president hectoring, threatening to fire, and belittling the attorney general and deputy attorney general is to allow them to witness also the degradation of the independent law enforcement function itself. For the departmental leadership to tolerate the repeated statements by the president of his expectation that their function is nothing more elevated than that of agents of his political power and protection is, at some level, to accede to the acceptability of those statements. Even if in practice, in the short term, law enforcement functions independently as a result, accepting this characterization of its function has to socialize over time the way people at the relevant agencies understand the jobs they are doing. It will drive honest people away, prevent good people from coming on board, and over time it will influence the way many people think about their work.

Perhaps even more important than the message that leadership's rope-a-doping sends to law enforcement officers is the message it sends to the public about law enforcement. For the public to see this kind of presidential behavior towards the attorney general and the deputy attorney general, for the public to see both men tolerate it, and for the public to see there be no consequences for it will, again over time, make it acceptable behavior. That’s the way political norms change—the way old norms get discarded and the way new ones develop. If it’s okay for the president to criticize the attorney general for recusing when it’s not convenient for his interests for the attorney general to do so, then why is not okay for him to demand as a condition of appointment that the attorney general promise not to recuse? And why is it not okay for a prospective attorney general to comply with such a demand? If it’s okay for the President to tweet that his political opponent should be investigated, why is it not okay for the attorney general to investigate those the President says should be criminally investigated? Why is it not okay for the President to order up such an investigation?

I’m not a fan of slippery slope arguments, as a general matter, but if any slope has ever been slippery, it is a slope in which we expect law enforcement leadership to rope-a-dope intolerable presidential demands but keep itself pure of compliance with those demands. If law enforcement leadership tolerates presidential behavior of this sort today and contents itself with passively resisting Trump’s demands, we should expect that the leadership of tomorrow will comply with those same demands.

Finally, resignations can have an important value as a forcing function. As long as members of Congress can deny that we face, as Jack puts it, “a kamikaze president” who is “bent on destroying the authority of the Justice Department,” they will remain in the relative comfort of denial and inaction. By contrast, if Sessions and Rosenstein were both to resign, particularly in conjunction with one another and particularly in combination with strong statements of the impossibility of ethical and independent law enforcement under the conditions the President has created, that would make continued denial much more difficult. Jack wrote yesterday that “The crazier Trump gets with law enforcement, the more the pressure will rise on Congress to do something more about it.” I agree. But when law enforcement leadership absorbs the craziness and carries on as though it were not happening, it actually relieves the pressure. It allows Congress to avert its gaze for longer.

In the end, more important than the question of resignation or not resignation is the question of whether or not law enforcement leadership will speak out loudly on behalf of independent law enforcement or suffer in silence. On this point, Jack and I agree completely: “Attorney General Sessions could and should speak out sharply against the President and in defense of the integrity of his Department.” The consequences of doing so would likely be, as Jack makes clear, to hasten Sessions’s removal. So the end result might well be the same. But whether the defense of independent law enforcement comes in the form of a resignation or the courting of a dismissal, it needs to happen. Minding the ship in silence until the president throws you overboard is not the right answer.