The First Test for Chief Justice Roberts? McConnell’s Organizing Resolution for Impeachment

How the chief justice deals with the question of whether the Senate will hear new evidence and testimony could illuminate how aggressive a role he intends to play throughout the trial.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

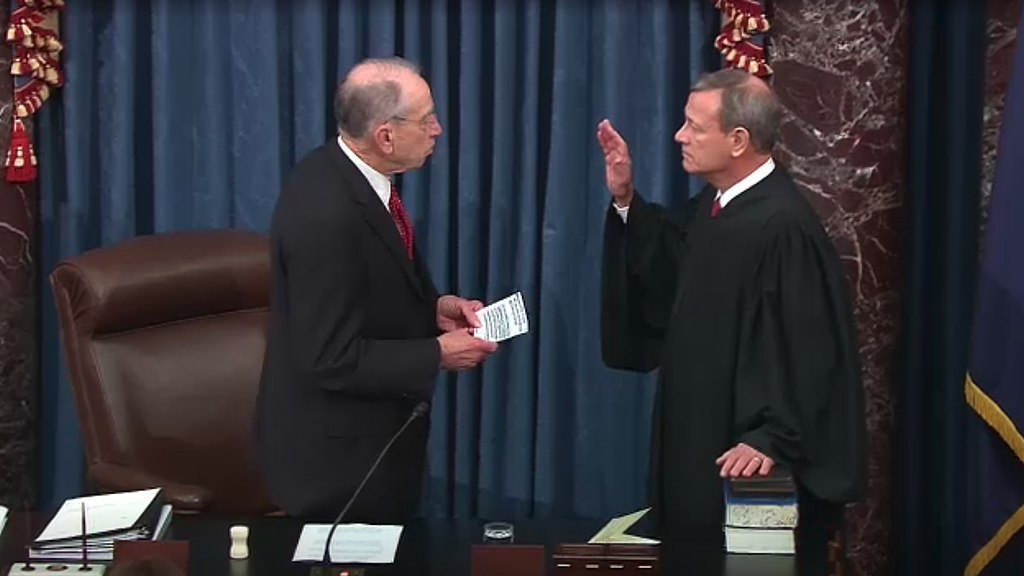

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi has passed the articles of impeachment to the Senate, the senators have sworn their oaths, and the impeachment trial of President Trump is set to begin on Jan. 21. But many things remain unresolved—among them, whether and to what extent the Senate will hear “new” evidence and testimony that was not a part of the House’s impeachment inquiry. And that question could end up speaking directly to another issue: how aggressive a role Chief Justice John Roberts will play in presiding over the Senate trial.

The House voted on the two articles of impeachment on Dec. 19 and voted on Jan. 15 to transmit them to the Senate. In the meantime, documents and statements from Lev Parnas—the indicted associate of Trump’s lawyer and fixer Rudy Giuliani—were released, implicating the president directly in efforts to obtain dirt on and investigations of the Bidens. In early January, the New York Times reported on behind-the-scenes consternation and haggling of executive branch officials over the legal consequences of the president’s decision to hold back $391 million worth of military assistance the Ukrainian military needed in its fight against Russian-backed separatists. That reporting, and related revelations concerning communications between the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Pentagon, makes clear that the decision to withhold the aid came from the president himself. And on Jan. 16, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a legal decision finding that OMB violated the Impoundment Control Act when it withheld from obligation the portion of Ukraine assistance funds appropriated to the Department of Defense.

But will senators get to consider any of this during the trial itself? The Rules of Procedure and Practice in the Senate When Sitting on Impeachment Trials do not directly address the issue of new evidence or new testimony. Rather, they simply provide that the House managers present their case, that the president or his counsel respond, and that the presiding officer (in this case, Roberts)

may rule on all questions of evidence including, but not limited to, questions of relevancy, materiality, and redundancy of evidence and incidental questions, which ruling shall stand as the judgment of the Senate, unless some member of the Senate shall ask that a formal vote be taken thereon, in which case it shall be submitted to the Senate for decision without debate; or he may at his option, in the first instance, submit any such question to a vote of the members of the Senate. Upon all such questions the vote shall be taken in accordance with the Standing Rules of the Senate.

So imagine that, as part of their case, the House managers seek to present new information obtained since the articles of impeachment were passed in the House. It would appear that under these rules, it would be up to the president’s defense counsel to object to evidence presented or testimony sought by the House managers. It would then be up to Chief Justice Roberts to decide how to handle it, and his decision could be overruled by the senators themselves.

If Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has his way, no new evidence would be allowed. One question that will arise—as early as Tuesday—is whether Roberts agrees and how, exactly, he will handle the issue as the presiding officer.

Press reports indicate that McConnell is seeking to pass an organizing resolution similar to the one passed unanimously in the Senate on Jan. 8, 1999, ahead of the Clinton impeachment trial. Democratic leadership in the Senate has not agreed to support any such resolution. The Senate will not consider such a resolution until Jan. 21, the day the trial begins, and McConnell has said he will not reveal the text of the resolution until next week.

The 1999 resolution was specific that the House had “until 12 noon on January 13” (the day before arguments began) to file “the record” and that “the record” would specifically consist of “those publicly available materials that have been submitted to or produced by the House Judiciary Committee, including transcripts of public hearings or mark-ups and any materials printed by the House of Representatives or the House Judiciary Committee pursuant to House Resolutions 525 and 581.” In other words, only materials that were an official part of the House record would be considered as the initial Senate record. The resolution goes on to specify that “[s]uch record will be submitted into evidence, printed and made available to Senators” (emphasis added). The House and the president had until 5 p.m. on Jan. 11 to file any motions permitted under the impeachment rules except for “motions to subpoena witnesses or to present any evidence not in the record.” Arguments on such motions could begin on Jan. 13, following which the Senate “shall deliberate and vote on any such motions.”

The Clinton resolution states that “[t]he presentation [by the House managers] shall be limited to argument from the record” (emphasis added). Thereafter, the president’s defense team presentation must be “with reference to the House presentation.” Senators then had an opportunity to question the parties via written submissions to the chief justice. Only after these phases were complete was it in order to make a motion to dismiss, as outlined by the impeachment rules, or a motion to subpoena witnesses and to present any evidence “not in the record.”

So if McConnell is able to pass an analogous resolution, the House managers would be prohibited from presenting new evidence. And the Senate majority leader has indicated he has 51 Republican votes to pass his resolution. But there is a question of whether such a resolution alters the existing Senate rules regarding impeachments. Normally 67 votes would be required to invoke cloture on debate—halting any filibustering and forcing senators to a vote—on a proposal to change the Senate rules.

This was not a live issue back in 1999, because the organizing resolution was agreed to unanimously. This time around, as Ed Kilgore points out, Democrats may argue that McConnell is trying to amend the rules and seek to force a vote at the 67-vote threshold. On the one hand, the resolution is not literally making amendments to the rules, and the Senate’s record of the vote on the 1999 resolution indicates it needed only 51 votes to succeed. But clearly, on a substantive level, such terms alter and constrain the bare-bones format laid out in the existing rules.

Here’s how this might play out: McConnell would introduce the organizing resolution and seek to pass it with 51 votes. If efforts to amend the resolution are unsuccessful, a Democratic senator would then make a point of order on the basis that 67 votes are required. And it would then be up to Roberts to rule on the point of order—presumably with the advice of the Senate parliamentarian, who will be at his side throughout the trial.

How Roberts handles this issue will likely be the first glimpse of what we can expect from Roberts in the trial going forward. He could rule with vigor—or timidity. Senators could accept the ruling—or any one senator could ask for a formal vote. Alternatively, Roberts could put the vote to members of the Senate without making a ruling or recommendation.

There has been a great deal of speculation on what role Roberts intends to play in the Senate trial. Will he engage actively, like Chief Justice Salmon Chase in the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson, or will he largely sit back and let the Senate do as it wishes, like Chief Justice William Rehnquist during Bill Clinton’s trial? Perhaps, thanks to McConnell, we may have an answer to that question as soon as the trial begins.