The Former National Security Adviser’s Sentencing Hearing: Flynncompetent Judging

Neither Michael Flynn nor Special Counsel Robert Mueller can be happy with the judge’s performance at yesterday’s sentencing hearing—and the public shouldn’t be either.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

A number of years ago, a group of singing lawyers put together an excellent parody song about the egomania of federal district judges. Set to the tune of the old Turtles song “Happy Together,” it opens: “Imagine me as God—I do. I think about it day and night. It feels so right to be a federal district judge and know that I’m appointed forever.”

L’Affaire Russe has long presented the American public with a master class in bad defense lawyering and white-collar subjects and targets run amok. The Dec. 19 sentencing hearing for disgraced former national security adviser Michael Flynn added a new element to the syllabus: bad judging.

Federal District Judge Emmet Sullivan, responding to some legitimate provocations, went on a grossly inappropriate rant that ultimately had the effect of bullying a defendant into deferring his sentencing—even though both the defendant and the prosecution were ready to proceed to sentencing and, indeed, even though there was no dispute between them as to what sentence the defendant should receive. Judge Sullivan’s irritation is understandable under the circumstances, and aspects of his reaction were reasonable, even constructive. But as the hearing wore on, Judge Sullivan looked more and more like the judge featured in the song, who triumphs: “I’m a federal judge and I’m smarter than you—for all my life. I can do whatever I want to do—for all my life.” He delivered a series of cringe-worthy lines, which he then had to retract. Neither Flynn nor Special Counsel Robert Mueller can be happy with what emerged—and the public shouldn’t be either.

The background to Wednesday’s hearing has two major elements—neither of which was mentioned explicitly at the hearing but both of which, we suspect, lurked in the shadows. The first was the case of George Papadopoulos, who—like Flynn—pleaded guilty to making false statements to the FBI in its early investigation of L’Affaire Russe. Papadopoulos played a double game at sentencing. In court, he expressed remorse for his actions, and Judge Randolph Moss gave him a sentence at the low end of the guidelines range, which suggests anything from no jail time to six months in jail for a first offense. Having received his sentence of 14 days in prison, however, Papadopoulos went on a media spree of conspiracy theorizing, suggesting that he would withdraw his guilty plea after discovering that he had been set up by the government, seeking to delay his time in prison, and, after that failed and he served his sentence, announcing the publication of a memoir with the auspicious title “Deep State Target.” He began this media spree earlier, truth be told—he first hinted a desire to withdraw from his plea agreement over the summer—but he kept quiet in the week before sentencing. Then he cut loose. Having declared in court that he took responsibility for his actions, Papadopoulos publicly portrayed himself as having been set up.

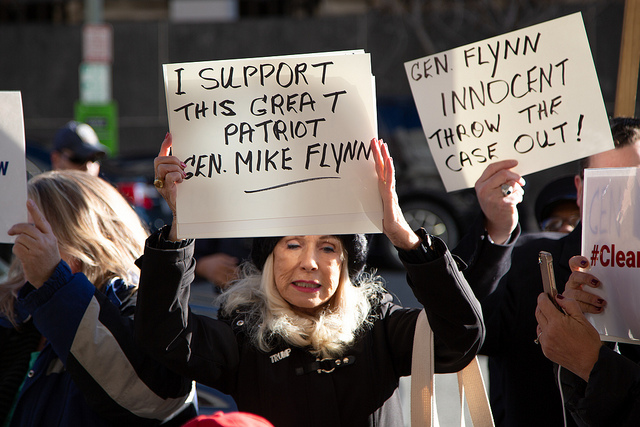

The second element was the conspiracy theorizing that developed around Flynn himself. The facts of the Flynn case aren’t actually complicated. There are some mysteries remaining—such as why he lied to the FBI—but there is no ambiguity about what happened. That, however, has not stopped a rash of conspiracy theories from erupting among President Trump’s supporters about how Flynn was set up, how he was lured into a “perjury trap” and how the FBI knew he wasn’t lying but proceeded anyway. Trump himself has gotten into the game, tweeting that the FBI “want[s] to scare everybody into making up stories that are not true by catching them in the smallest of misstatements” and, the day before Flynn’s sentencing, that it would be “interesting to see what he has to say, despite tremendous pressure being put on him … There was no Collusion!”

Until Dec. 11, when his lawyers filed his sentencing memorandum, Flynn himself had not played this game. He cooperated with Mueller’s investigation seriously, the Mueller team has made clear, and he did so without any evident side games. But in the sentencing memo, Flynn’s lawyers tried to play it both ways. They emphasized Flynn’s cooperation. Yet they also argued that the FBI agents sent by then-Deputy Director Andrew McCabe had not warned Flynn of the criminal penalty for making false statements to law enforcement; suggested that McCabe had dissuaded Flynn from having a lawyer present; and hinted coyly that Mueller’s dismissal of FBI agent Peter Strzok, who interviewed Flynn, for the appearance of bias over anti-Trump texts should have some kind of bearing on the legitimacy of Flynn’s plea. The sentencing memo played off a long-running conspiracy theory that Flynn had been entrapped and set off a firestorm of speculation on the pro-Trump right.

At the hearing, Flynn lawyer Robert Kelner argued that Flynn had not been attempting to cast doubt on the integrity of the plea:

The principal reason we raised these points in the brief was to attempt to distinguish the two cases in which the special counsel’s investigation has resulted in incarceration, the Papadopoulos and Van der Zwaan cases in which the special counsel has pointed out as aggravating factors the fact that those defendants had been warned and the fact that those defendants did have counsel and lied anyway, and we felt it was important for the court that those aggravating circumstances do not exist in this case relevant to sentencing.

But Gen. Flynn has been, I think, clear from the beginning and will be clear again that he fully accepts responsibility, stands by his guilty plea, which was made based on knowing and willful conduct.

We did think there was information produced in the Brady process that Your Honor might want to see, and that was relevant strictly to the question of the history and circumstances of the case for sentencing purposes.

This explanation notwithstanding, under the circumstances it was not crazy for Judge Sullivan to wonder whether Flynn was pulling a Papadopoulos: saying one thing in court, getting a light sentence and then going on public relations offensive as a purported victim. Likely sharpening Judge Sullivan’s problem was the fact Flynn had pleaded before a different judge, who then recused. So Flynn’s colloquy in which he took responsibility for the crime for which Sullivan was sentencing him had taken place both more than a year ago and before someone else.

Under these circumstances, it is understandable that the judge would be concerned with preventing Flynn from talking out of both sides of his mouth. And Judge Sullivan’s initial step to stop that from happening was reasonable. Flynn’s briefing, he said, “concerned the Court, as he raised issues that may affect or call into question his guilty plea and, at the very least, maybe his acceptance of responsibility. As such, the Court concludes that it must now first ask Mr. Flynn certain questions to ensure that he entered his guilty plea knowingly, voluntarily, intelligently, and with fulsome and satisfactory advice of counsel.”

So Judge Sullivan made Flynn do just that. Under oath, he effectively redid Flynn’s plea colloquy, making the defendant address on the record each of the following questions:

- “Do you wish to challenge the circumstances on which you were interviewed by the FBI?”

- “Do you understand that by maintaining your guilty plea and continuing with sentencing, you will give up your right forever to challenge the circumstances under which you were interviewed?”

- “Do you have any concerns that you entered your guilty plea before you or your attorneys were able to review information that could have been helpful to your defense?”

- “At the time of your Jan. 24, 2017 interview with the FBI, were you not aware that lying to FBI investigators was a federal crime?”

- “Do you seek an opportunity to withdraw your plea in light of [new] revelations” referred to in your brief?

- “Are you satisfied with the services provided by your attorneys?”

- “Do you want the court to consider appointing an independent attorney for you in this case to give you a second opinion?”

- “Do you feel that you were competent and capable of entering into a guilty plea when you [pleaded] guilty on Dec. 1, 2017?”

- “Do you understand the nature of the charges against you[,] the consequences of pleading guilty?”

- “Are you continuing to accept responsibility for your false statements?”

- “Do you still want to plead guilty, or do you want me to postpone this matter, give you a chance to speak with your attorneys further, either in the courtroom or privately at their office or elsewhere, and pick another day for a status conference?”

Flynn answered all of these questions in a fashion consistent with his plea, pulling the rug out from under the conspiracy theorists. Judge Sullivan then went on to question his lawyers:

- “Do you have any concerns that potential Brady material”—that is, exculpatory evidence material to the defendant’s guilt or innocence under Brady v. Maryland—"or other relevant material was not provided to you?”

- “Do you contend that Mr. Flynn is entitled to any additional information that has not been provided to you?”

- “Do you wish to seek any additional information before moving forward to sentencing?”

- “Do you believe the FBI had a legal obligation to warn Mr. Flynn that lying to the FBI was a federal crime?”

- “Is it your contention that Mr. Flynn was entrapped by the FBI?”

- “Do you believe Mr. Flynn’s rights were violated by the fact that he did not have a lawyer present for the interview?”

- “Do you believe his rights were violated by the fact that he may have been dissuaded from having a lawyer present for the interview?”

- “Is it your contention that any misconduct by a member of the FBI raises any degree of doubt that Mr. Flynn intentionally lied to the FBI?”

Kelner answered all of these questions in the negative. “And you’re not asking for a postponement to give more time to whether you wish to file a motion to attempt to withdraw Mr. Flynn’s plea of guilty?” asked the judge.

Responded Kelner: “We have no intention and the defendant has no intention to withdraw the guilty plea, and we’re certainly not asking Your Honor to consider that. We’re ready to proceed to sentencing.”

On this basis, Judge Sullivan declared, “I conclude that there was and remains to be a factual basis for Mr. Flynn’s plea of guilty. As such, there’s no reason to reject his guilty plea and I’ll, therefore, move on to the sentencing phase.”

Had the judge stopped there and actually proceeded to sentence Flynn, the hearing would have been a good day’s work. Judge Sullivan had managed to create a strong record rebutting nearly every aspect of the conspiracy theories around the Flynn interview. And while the conspiracy theories would remain—conspiracy theories always remain—the record would make it difficult for Flynn to participate in propagating them.

But Judge Sullivan did not stop there. He first turned to the government and asked whether Flynn was still cooperating, extracting the statement from the special counsel’s office that it was still a “possibility” that Flynn’s further cooperation would be necessary. This seemed to bother the judge, because—as he put it—courts don’t normally proceed to sentencing until cooperation is complete. He did not seem mollified by the assurance from the special counsel’s office that Flynn had provided the overwhelming majority of the cooperation the government could expect of him already. When prosecutor Brandon Van Grack pointed out that Flynn’s cooperation had been essential to the indictment the day before of two of his former business partners as unregistered Turkish agents in the Eastern District of Virginia, Judge Sullivan turned around and asked whether Flynn himself could have been charged in that indictment. Van Grack agreed that he could have been and acknowledged that Flynn’s testimony might be necessary in that case. “So if you proceed to sentencing today,” he said to Flynn, “the Court will have to impose a sentence without fully understanding the true extent and nature of your assistance. Do you understand that?” Flynn said that he did.

And that is where the hearing really went off the rails. Because Judge Sullivan then proceeded to begin what can only be read as a sustained effort to pressure Flynn into delaying his sentencing. He warned him that “the sentence the Court imposes today, if sentencing proceeds, may not be the sentence that you would receive after your cooperation ends.” He then all but explicitly warned Flynn that if sentencing proceeded, he would impose jail time—over the recommendation of prosecutors. “I’m going to be frank with you,” he said. “This crime is very serious. As I stated, it involves false statements to the Federal Bureau of Investigation agents on the premises of the White House ... by a high-ranking security officer….” He would listen to the extenuating factors, he said, “but I’m also going to take into consideration the aggravating circumstances, and the aggravating circumstances are serious.” Judge Sullivan said that he was “not hiding my disgust, my disdain for this criminal offense.”

Having essentially threatened the defendant with jail time if he proceeded to sentencing on schedule, Judge Sullivan then turned to Van Grack and compounded the impropriety. First he demanded to know whether the underlying conduct about which Flynn had pleaded guilty could have been charged as a separate offense; Van Grack acknowledged that it could be construed as a Logan Act violation but said that the government didn’t consider seriously such a charge.

The judge then bizarrely asked whether Flynn’s conduct was “treasonous.” Van Grack, perhaps taken off guard, blandly declared that treason “was not something that we were considering in terms of charging the defendant.” But Judge Sullivan pushed: “Hypothetically, could he have been charged with treason?” The judge later insisted that he hadn’t been suggesting Flynn had committed treason and, indeed, acknowledged that he “couldn’t tell you what the elements [of the offense] are anyway.” That latter point was clear enough, since treason—as a legal matter—is defined in the Constitution and requires a state of war. Van Grack later had to clarify that the “government has no reason to believe that the defendant committed treason” and has “no concerns with the respect to the issue of treason.”

When Kelner had the temerity to compare Flynn’s case to that of Gen. David Petraeus, Judge Sullivan again went rogue, saying he didn’t agree with the decision to let Petraeus plead to a misdemeanor—before then acknowledging that he didn’t know all the facts of the case. Later in the hearing, he did it again, declaring that “I don’t agree with the Petraeus sentence”—before backtracking and allowing, “Maybe there were extenuating circumstances. I don’t know. It’s none of my business, but it’s just my opinion.”

By the time Judge Sullivan was done with these displays, it was clear to Flynn’s counsel that proceeding to sentencing as planned was too dangerous. So Kelner capitulated: “We are prepared to take Your Honor up on the suggestion of delaying sentencing so that he can eke out the last modicum of cooperation in the [Eastern District of Virginia] case to be in the best position to argue to the Court the great value of his cooperation."

What had begun as a laudable effort debunk conspiracy theories ended as rank judicial bullying of a defendant in the presence of no dispute as to outcome between that defendant and his prosecutors.

The redeeming factor in this judicial ego trip is that it likely won’t matter much. Flynn has cooperated to Mueller’s satisfaction after all. Sullivan may well prove less generous to him than another judge might have in sentencing, or he may find, as Kelner clearly hopes, that the additional months will cool down his temper. But it won’t affect the larger progression of the Russia investigation.

It was, however, a flamboyant display of exactly how district court judges shouldn’t act, a display of the attitude parodied in the federal district judge song: “My decisions cannot be questioned by you: I'm always right! And my wise discretion is never abused—for all of my life!”

Lawyers practicing before courts have to hide their disdain for such behavior. Singing parodists and legal commentators do not.