Four Hearings and a Funding Stream

A dispatch from Judge Cannon’s hearings on special counsel funding, modifying Trump’s bond conditions, attorney-client privilege, and Trump’s challenges to the validity of the warrant.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

June 24, 2024

It’s a Monday morning, June 24, at the federal courthouse in Fort Pierce, Florida. The Supreme Court hasn’t yet ruled in the immunity matter—or even in the Fischer case. So pretend you don’t know anything about that. Yeah, yeah, this dispatch has taken a little while. You want it faster? Then you spend a week in Fort Pierce as Judge Aileen Cannon holds a string of day-long hearings and write 17,000 cumulative words on those hearings yourself.

So, yeah, in this dispatch it’s last Monday morning, June 24, and Judge Cannon is set to hold yet more hearings on motions related to Donald Trump’s criminal prosecution in the Southern District of Florida. On Friday, she heard arguments on the legality of Special Counsel Jack Smith’s appointment. On the agenda today: the legality of the special counsel’s funding stream.

At 10:00 a.m. sharp, it’s “all rise” time as Judge Cannon enters the courtroom.

The parties introduce themselves. For the Special Counsel’s Office, it’s Jay Bratt and James Pearce, who are seated at the counsel’s table on the right-hand side of the room. Their boss, Special Counsel Jack Smith, is seated in a chair a few feet behind them. In the gallery, I spot other long-time members of the special counsel’s team, including Julie Edelstein, a counterintelligence and Espionage Act expert, and Michael Thakur, a Miami-based federal prosecutor.

On the defense side, it’s Emil Bove, Todd Blanche, Kendra Wharton, and Lazaro Fields on behalf of Trump. The former president’s co-defendant, Waltine Nauta, is represented today by Stanley Woodward and Sasha Dadan. As for Trump’s other co-defendant, Carlos De Oliveira, it’s Donald Morrell and John Irving.

Judge Cannon explains that she scheduled today’s hearing for argument on the second half of Trump’s motion to toss out his criminal charges based on the allegedly unlawful appointment and funding of the Special Counsel’s Office. While Judge Cannon heard argument on Friday regarding the portion of that motion that relates to the Constitution’s Appointments Clause, the subject of today’s hearing is the Appropriations Clause, which states that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” In other words: The Appropriations Clause establishes that the payment of money from the Treasury must be authorized by statute.

To be sure, the Justice Department has funded the special counsel’s work under the auspices of a statute, called the Department of Justice Appropriations Act of 1988. Specifically, when paying Smith’s expenses, the Justice Department has relied on a “permanent indefinite appropriation,” which the act established to “pay all necessary expenses of investigations and prosecutions by independent counsel appointed pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 591 et seq. or other law” (emphasis added).

In the motion that is the subject of today’s hearing, however, Trump contends that the Justice Department improperly relied on the permanent appropriation. In support of that argument, Trump’s brief points out that Smith is not an “independent counsel appointed pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 591”—a reference to the now-lapsed independent counsel law, which established a procedure by which a panel of federal judges would appoint a special prosecutor at the request of the attorney general.

The crux of Trump’s motion, however, rests on the idea that Smith also doesn’t qualify for the permanent appropriation because he is not an “independent counsel” appointed pursuant to some “other law.” He claims that Smith was not appointed pursuant to “other law” because the attorney general lacks statutory authority to appoint a special counsel. What’s more, Trump’s motion asserts that Smith is not an “independent” counsel as contemplated by the appropriations statute.

All of which leads Trump to conclude that the permanent appropriation does not apply to Smith, that the Justice Department violated the Appropriations Clause by drawing funds from the permanent appropriation to fund Smith’s work, and that the charges against Trump should be dismissed.

Judge Cannon, for her part, set aside half a day to hear arguments on this aspect of Trump’s motion. Later this afternoon, the parties are set to argue over the special counsel’s motion to modify Trump’s bond conditions.

Now, the judge directs her attention to Bove. Mr. Bove, she says, will you be arguing today.

Yes, Your Honor, Bove confirms. He hurries to the lectern.

When he arrives, Bove asserts that the Special Counsel’s Office should not have accessed the permanent indefinite appropriation and should not have access to it going forward. He argues that there are two flaws in the government’s brief opposing Trump’s motion.

First, Bove addresses the government’s statutory interpretation argument. In its brief, the Special Counsel’s Office argues that the text of the appropriations statute applies to the special counsel’s work because Smith is an “independent counsel” appointed by “other law.” Bove, however, tells Judge Cannon that the government asks the court to adopt a “strained” interpretation of the statute’s text.

The second problem, Bove continues, is that the government’s arguments on the appropriations issue are in “irreconcilable tension” with its arguments on the Appointments Clause issue that was the subject of Friday’s hearing. He’s alluding to the fact that the government, during Friday’s hearing, emphasized the degree to which the attorney general can supervise or direct the special counsel’s work. At the same time, the government’s brief on the Appropriations Clause challenge contends that the special counsel is truly “independent” as that term is used in the appropriations statute.

Bove doesn’t mention that the same criticism could be leveled at his own arguments: On Friday, Bove argued that the special counsel is subject to little oversight by the attorney general. Today, he intends to argue that the special counsel is not “independent” enough to access the permanent appropriation.

Turning now to the text of the appropriations statute, Bove reminds Judge Cannon that his arguments are focused on the idea that Smith is not an “independent counsel” appointed pursuant to “other law.” With respect to the phrase “other law,” Bove says his argument relies on the statutory authorization issues discussed during Friday’s hearing. The idea is that the attorney general doesn’t hold statutory authority to appoint a special counsel and, as such, that Smith was not appointed pursuant to “other law” as required by the appropriations act.

Judge Cannon interjects: Would you agree that your “other law” argument on the appropriations issue “travels together” with your arguments regarding the attorney general’s appointment authority? In other words: The judge wants to know if Bove’s “other law” argument necessarily depends on how she rules on the issue of the attorney general’s appointment authority.

Yes, Your Honor, Bove replies. And to that end, we would incorporate our arguments discussed during Friday’s hearing.

Judge Cannon then asks Bove to address the issue of “standing” raised in the government’s brief. She’s talking about the special counsel’s argument that Trump does not have “standing” to seek dismissal of his charges based on the source of the money used to fund Smith’s work. Generally, “standing” refers to the idea that courts only adjudicate a claim if the challenged action caused injury to the litigant. In its brief, the government argues that the special counsel’s reliance on the permanent indefinite appropriation did not injure or prejudice Trump. According to the government, the indictment was not caused by the identity of the funding mechanism because the Justice Department could have funded the special counsel’s work through an alternative appropriations mechanism.

What is the cognizable injury suffered here? Judge Cannon asks.

Bove identifies the relevant injury as the “imminent threat” to Trump’s personal liberty that will result if he is convicted. He points to a U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit case, United States v. McIntosh, in which the court held that a potential conviction constitutes a justiciable injury for standing purposes.

Next, Judge Cannon clarifies how Bove’s argument relates to the Appropriations Clause. In the special counsel’s brief, she observes, there’s a suggestion that you aren’t actually raising a constitutional challenge. Are you in fact bringing a challenge under the Appropriations Clause?

After Bove confirms that he is indeed relying on the Appropriation Clause, Judge Cannon interjects: Your argument is that under the Appropriations Clause the payment of money has to be authorized by statute, but in this case it was not, so that violates the Appropriations Clause?

Correct, Bove replies.

Having clarified the substance of Bove’s argument, Judge Cannon turns to the structure of the permanent indefinite appropriation. Is there a cap on the funding? she inquires.

No, Bove says, there’s no cap on the funding. And that’s one reason why, from a separation of powers perspective, to be very “wary” of who can access this funding and why, especially in the context of a criminal defendant with important rights in a proceeding like this. And that’s why the court should take a “hard look” at the issue being raised here.

Judge Cannon follows up: Are you familiar with any authority on the constitutionality of a “fully unbound” appropriation? Wasn’t there a cap in the CFPB case? she asks.

The latter question is a reference to the Supreme Court’s decision in Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. Community Financial Services Association of America, in which the court upheld the constitutionality of the funding structure of a regulatory agency, the CFPB. When Congress established the CFPB in 2010, it created a mechanism by which the agency would be funded that is independent of the annual congressional appropriations process. Instead, Congress authorized the CFPB to draw from the Federal Reserve System an amount that its director deems “reasonably necessary” to carry out the agency’s work—so long as that sum did not exceed an inflation-adjusted cap. After a group of litigants challenged this funding arrangement, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that the CFPB’s financial independence violates the Appropriations Clause and the “constitutional separation of powers.” The Supreme Court disagreed, holding that the funding statute satisfies the Appropriations Clause because it authorizes expenditures from a specified source of public money for designated purposes.

Ahead of today’s hearing, Judge Cannon issued a sua sponte order that instructed the parties to submit supplemental briefs addressing the impact of the CFPB case on Trump’s claim that the special counsel is not lawfully funded. The lack of a cap on the special counsel’s “permanent indefinite appropriation” did not feature prominently in Trump’s supplemental briefing. But it has, apparently, piqued the interest of Judge Cannon.

Now Bove, responding to Judge Cannon’s inquiries on this point, says that yes, the funds the CFPB can draw from the Federal Reserve are limited by a percentage-based cap.

How does that play into your argument?

It highlights the separation of powers problem, Bove contends. The Special Counsel’s Office is able to access an indefinite, infinite budget to fund at least two prosecutions in different districts. There’s no check on the scope of what’s going on here, he asserts.

Moving on, Bove turns to his statutory interpretation argument. He focuses, first, on the phrase “other law” in the appropriations statute. According to Bove, the government’s position is that the Reno regulations—the Justice Department’s regulations that govern the appointment, oversight, and removal of a special counsel—can serve as “other law” for purposes of the appropriations statute.

But that argument is foreclosed to the government, Bove contends. On Friday, the Special Counsel’s Office claimed that the attorney general has sufficient supervision over the special counsel because the Reno regulations can be rescinded at any time. But that means the Reno regulations are not “other law” as that term is used in the statute, Bove continues. He says that the regulations were carved out from the usual notice-and-comment process under the Administrative Procedures Act, which establishes a procedure by which the public can opine on a proposed regulation or rescission before the agency’s decision is finalized. When Attorney General Janet Reno exempted the special counsel regulations from that process in 1999, her reasoning relied in part on the idea that the special counsel regulations are not “substantive” rules.

Bove, citing a Supreme Court case called Chrysler Corp. v. Brown, explains that only substantive agency rules have the “force of law.” As such, he concludes that under Chrysler “these regulations cannot be ‘other law’ for purposes of the appropriation.”

Anything further on the “other law” argument? asks Judge Cannon.

No, judge, Bove answers.

Now Judge Cannon wants to talk about remedies. You’re seeking dismissal here, she observes, but I don’t understand your motion to be seeking any sort of injunction on continued spending. Is that correct?

That’s correct, Bove replies.

Judge Cannon then turns to the other statutory interpretation argument in Trump’s motion: that the special counsel does not qualify as an “independent counsel” within the meaning of the appropriations statute. In support of that argument, the brief compares the degree of independence of an independent counsel appointed under the now-defunct independent counsel law to the degree of independence afforded to the special counsel under the current regulatory framework. Are you still persisting in the position that there’s a mismatch in the degree of independence? Judge Cannon wonders aloud.

There’s a mismatch, Bove asserts, and an “irreconcilable difference” between the government’s position on independence under the Appointments Clause and the Appropriations Clause. On Friday, they said that the special counsel is not independent of the attorney general. But today, he continues, they have to say that the special counsel is independent to access the appropriation. Our position is that both cannot be true, he says.

Judge Cannon wants Bove to be more specific. Setting aside that potential tension for a moment, what is the comparison? If you were to do a side-by-side of the special counsel regulations versus the independent counsel act, what are the differences between the two with respect to the degree of independence?

Bove rattles off a list of several reasons why, in his view, the Reno regulations afford a lesser degree of independence to special counsels compared to the independent counsel law. For one thing, he says, under the independent counsel law, a panel of judges selected the special prosecutor. But under the Reno regulations, the attorney general decides. What’s more, he notes that under the old law, an independent counsel was empowered with the “full scope of the authority of the attorney general.” By contrast, under the Reno regulations, this authority is restricted to the authority of a United States Attorney. The attorney general under the current regulatory regime can also review action by the special counsel and decide that such action “should not be pursued,” he says.

If this sounds inconsistent with what Bove argued during Friday’s hearing on the Appointments Clause, that’s because it is.

And Judge Cannon, for her part, wants an explanation. But you've argued that the special counsel is taking inconsistent positions, she tells Bove. Aren’t you just doing the same thing, but flip-flopped? For your Appropriations Clause argument, you want to say there is insufficient independence. But with respect to the question of whether the special counsel is a superior or inferior officer under the Appointments Clause, you’re taking the opposite view.

Bove explains that Trump’s “principal” argument is his Appointments Clause argument. And with respect to the Appropriations Clause, he says, we’re very focused on the “other law” language in the statute. That interpretation is consistent with our Appointments Clause arguments, Bove continues. “This is our alternative argument.”

Judge Cannon clarifies: But with respect to the degree of independence, what I’m hearing is that it’s an alternative argument to the principal submission, which is that there is no “other law” by which the special counsel was lawfully appointed. Is that correct?

Correct.

With that clarification behind him, Bove further elaborates on the distinctions between the degree of independence under the Reno regulations versus the now-lapsed independent counsel law. Previously, he explains, independent counsels were only required to comply with written policies of the Justice Department. But according to Bove, the Reno regulations expanded that language to cover “rules, regulations, procedures, practices, and policies.” He adds that the removal provisions under the independent counsel law did not “contemplate removal over disagreements between the attorney general and the special counsel relating to how a case should proceed.” The Reno regulations, by contrast, do contemplate removal related to how prosecutorial discretion should be exercised.

Bove wraps up by reminding Judge Cannon of the “bottom line”: Under the Appropriations Clause, for the separation of powers to operate “as it must,” the special counsel can only draw an appropriation where his conduct and his activities meet the text of what the statute authorized. “And because there is no ‘other law,’ and because for purposes of this motion we also think that independence is a real problem, this appropriation should not be accessed,” he concludes.

“Thank you, Mr. Bove,” Judge Cannon says. “Let me hear from counsel for the special counsel.”

Pearce, who also argued the Appointments Clause issue last week, strides to the lectern to argue on behalf of the government.

“Consistent with longstanding Department of Justice practice,” Pearce begins, “the government has funded the Special Counsel through a congressionally-enacted permanent indefinite appropriation.” Under the plain terms of that statute, Pearce continues, the special counsel is an “independent counsel” appointed by “other law,” including 28 § 515(b) and 533(1), as discussed “extensively” last week.

Judge Cannon interjects: So you agree that the “other law” is a statutory law that you’ve pointed to elsewhere?

We do, Pearce replies. I think I heard my friend on the other side suggest that we’re relying on the Reno regulations, Pearce says. “We think it is statutory law.”

And you agree this is a “limitless” appropriation? Judge Cannon asks.

Pearce confirms the appropriation “does have that function.”

Judge Cannon follows up by asking Pearce if he can point her to any comparable “limitless” appropriation?

Pearce, for his part, is prepared to answer this question. He points to a document published by the Government Accountability Office (GAO)—called the “Handbook on Federal Appropriations Law.” The Handbook, he says, defines a “permanent indefinite appropriation,” explaining that it is not limited by time or amount. And it provides some examples, Pearce says, including 31 U.S.C. § 1304 and 31 U.S.C. § 1322(b)(2).

Sensing that Judge Cannon seems to be concerned by the lack of a cap on the special counsel’s funding stream, Pearce addresses the CFPB decision. I don’t read the Supreme Court’s decision in the CFPB case to rely on the fact that the appropriation was subject to an inflation-adjusted cap, he says. The court described the cap “by way of background,” but it only identified “source” and “purpose” as what’s required for a statute to comply with the Appropriations Clause.

Judge Cannon doesn’t seem to agree. “Well, the thrust of that decision does seem to be repeatedly focused on the existence of a cap.” That does “play into” the majority’s rationale, she says.

Pearce moves on to his statutory interpretation argument. He says it really “boils down” to this: “What is an independent counsel?” The authorities, Pearce says, all answer that question in the affirmative: the special counsel is an “independent counsel” as that term is used in the appropriations statute. In support of this argument, he cites regulations, GAO reports, judicial decisions in other jurisdictions, and the “longstanding practice of the Department funding eight special counsels under this appropriation with congressional acquiescence.”

Before Pearce can continue, the judge cuts him off. “The doctrine of congressional acquiescence is not the most robust doctrine, I think case law would indicate,” she says. So can we just focus on the “other law” language in the statute? I take your position to be that your arguments carry over completely from the Appointments Clause context, she says. Is that right?

Yes, Pearce confirms. And I have no reason to repeat those arguments here, unless the court wants to hear them again, he adds.

“No, no, that’s okay.”

Judge Cannon turns to the subject of the special counsel’s expenditures. “Now, I noticed there were some reports on the special counsel’s web page indicating the expenditures for six months,” she says. Is it the regular practice to issue expenditure reports covering a six-month period?

Yes, that’s my understanding, Pearce replies. The reports typically cover a six-month period, though the precise timing as to when they are released may vary, he says. He adds that the latest report ends in March 2024, though it hasn’t been made public yet.

How long does it take for the reports to become public? Because we’re in June now, Judge Cannon observes.

“That is something that is, I think, outside of our office’s control,” Pearce responds. He isn’t entirely sure, but he “thinks” the GAO may be involved in some capacity with respect to when the expenditure reports are publicly released. Looking at reports from previous special counsels, sometimes it has taken as long as a year, he says. But for this special counsel, I think it is “considerably less” of a period than that.

Judge Cannon follows up: What is the review process? “I know the regulations reference the initial establishment of a budget and review by the Attorney General,” she says. “But what is the continuing review process for the budget proposals and the expenditures?”

Pearce, who came prepared to argue a statutory interpretation question, is less prepared to discuss the minutiae of budget review practices. I don’t know precisely, he replies, other than “what I understand to be generally accepted accounting practices” to track the funds and to make sure that they are enumerated for purposes of identifying an expenditure.

Judge Cannon now directs Pearce’s attention to the “actual expenditures” in the special counsel’s expenditure reports. “There is one from the period of November 18 of 2022 through March of 2023, which lists the ‘Total SCO Expenditures’ at $5.4 million,” she notes. “And then if you refer further down in the report, there’s a reference to ‘DOJ component expenses’ for another $3.8 million, again, for the six-month period.”

I just have a clarifying factual question about these expenses, the judge continues. Is the $3.81 million for “DOJ component expenses” also being paid for through the permanent indefinite appropriation?

“Top line answer: I don’t know,” Pearce replies. I believe everything is paid for from the permanent appropriation, he explains, with the caveat that there are some individuals—Pearce included—who are “on detail” from other parts of the Justice Department. “I believe those individuals are funded by their existing components, but I don’t want to say I’m certain about that,” he adds.

I’m just trying to get a sense, monetarily, for the expenditures during that six-month period, Judge Cannon explains. The report says, “Total SCO Expenditures: 5.4 million.” But is it more like $9 million when you include the expenditures for the Justice Department component expenses that are also being paid for by the permanent indefinite appropriation?

I’m not sure, Pearce says. We can certainly give the court something supplementally to enumerate with more precision, he says. But I don’t know the answer.

“I think it would be helpful, since these are public documents,” Judge Cannon replies. I’m just trying to understand what the “full universe” of expenditures looks like, she explains. “Since this is an Appropriations Clause challenge, I do think it provides some helpful context for the amount of money that is actually being spent.”

“I think that’s fair,” Pearce says. But just to be clear, he continues cautiously, I’m not aware of any case in which a court has found that the total amount of the expenditure is relevant to an Appropriations Clause challenge.

Before he can continue, Judge Cannon interrupts: “But when it’s limitless, I think there is a separation of powers concern that one needs to take a look at.”

Pearce tries to say something else, but the judge fires back: “Don’t interrupt, please.”

Pearce apologizes and then asks Judge Cannon for permission to respond. She allows it.

So I agree, Pearce says, that the separation of powers issue you have just described is “absolutely” the thrust of the Fifth Circuit’s opinion in the CFPB case, which the Supreme Court then reversed. I read the Supreme Court’s decision as saying that the court is focused on whether the statute identifies the “source” and “purpose” of the appropriation, he says.

Well, the Supreme Court didn’t have occasion to address the remedy in CFPB because it found a lawful appropriation, Judge Cannon replies. Would you agree with that?

“I would certainly agree that there was no cause to address remedy there,” Pearce says.

Judge Cannon pivots. You’ve mentioned in your opposition brief that the department could readily fund the special counsel’s work through an alternative source, she says. “I wanted to give you an opportunity to identify what that other alternative would be.”

Speaking at a “high level of generality,” Pearce replies that the Justice Department has appropriated over a billion dollars in the 2023 appropriations cycle. And I can represent to the court that the government “is prepared” to use money that is appropriated to the Department of Justice to fund the work of the special counsel, he says.

And what are your views, if any, about prior expenditures? Judge Cannon asks. Elaborating on this question, she explains that she wants to know what to do about prior expenditures if there is “a need to tap an alternative funding source.”

“Retrospectively, there should be no effect or change whatsoever,” Pearce replies. Citing Supreme Court precedent, he explains that the court has suggested in various contexts that “you don’t look retrospectively to try to undo acts that have [already] happened.”

Next, Judge Cannon directs Pearce to address one argument raised in the government’s brief, which suggests that Trump’s motion doesn’t present a constitutional challenge to begin with.

Pearce replies that he “doesn’t see a whole lot turning on the answer to this question one way or another.” In our view, they have raised a statutory interpretation question and, thus, a statutory issue.

But that’s what I want to develop here, Judge Cannon interjects. “I mean, how is it not a constitutional challenge, when you have the Appropriations Clause requiring or indicating that no money shall be drawn from the Treasury but in consequence of appropriations made by law?” And you have Supreme Court cases saying that, in assessing this question, a court must determine whether payment of money was authorized by a statute. That's the argument being raised here, she asserts. So how is it not a constitutional challenge?

Pearce reiterates that he doesn’t want to “fight this too much” because he doesn’t think much turns on it.

But that response doesn’t satisfy Judge Cannon, who now appears visibly irritated with Pearce. Do you have “any basis” to believe that it’s not a constitutional challenge? “I haven’t heard anything in your presentation to dissuade from the view that it is, in fact, a constitutional challenge,” she adds.

Again, Pearce replies, “it’s not a hill on which I feel inclined to die.”

For now, at least, this appeases the judge. Well, I certainly don’t want that to happen, Mr. Pearce, she says. Then: “You’re doing a very fine job arguing.”

Pearce returns, at long last, to one of the key issues actually raised in Trump’s motion: whether the special counsel constitutes an “independent counsel” under the appropriations statute. Judge Cannon, for her part, asks Pearce to address how the special counsel’s degree of independence under the “removal provisions” in the Reno regulations versus the removal provisions in the independent counsel law.

Both provide that the attorney general can remove a special counsel “for cause,” Pearce explains. He doesn’t think there’s any difference between the two in that respect. But unlike the old statutory framework, the attorney general under the current regulatory regime also has the power to unilaterally modify or rescind the special counsel regulations, he says. I don’t think that means there is no independence, Pearce continues. “It just makes sure that the attorney general is, in fact, the principal officer supervising and overseeing the special counsel.”

Are you aware of any occasion in which a special counsel regulation has been rescinded? Judge Cannon asks.

“I am not aware of that, no.”

Okay, the judge replies. She points out that there’s a “lot of reliance on history and historical practice” in the special counsel’s filings. But “in reality,” has a regulation like this ever actually been rescinded? Is it, really, a sort of “illusory possibility”?

I don’t think that’s correct, Pearce asserts. He then argues that what happens “in reality” is not the relevant question in determining whether an officer is a principal or inferior. It’s not a question of whether there was an exercise of potential powers, he says. Instead, courts look to the statutory or regulatory framework and ask how power is structured between the relevant institutional actors.

Though this hearing is ostensibly about Trump’s appropriations argument, Judge Cannon now seems to have her mind on the Appointments Clause issue. She follows up by observing that the government’s brief uses the term “regulatory special counsel.” And I have seen that term in some of the materials, she says. What does that mean, a “regulatory special counsel”?

I think that’s actually a misnomer, Pearce replies. He explains that the term is used to differentiate between a prosecutor who had been appointed under the independent counsel law versus a prosecutor who had been appointed under the attorney general’s independent statutory authority and who operated under regulations established by the Justice Department. But while a “regulatory special counsel” governed the Justice Department’s regulations, Pearce explains, the appointment and the regulations were backed up by statutory authority. Specifically, he cites the statutes discussed during Friday’s hearing: 28 U.S.C. § 515(b) and 28 U.S.C. § 533.

“Well, it’s just interesting,” Judge Cannon says with some skepticism. “I mean, why would you call them a regulatory special counsel? It just kind of begs the question: Well, where is the statutory authority if we’re describing them as such?”

I think the question you just asked is why I think it’s a misnomer, Pearce replies.

“But maybe it’s telling,” Judge Cannon shoots back.

Observing this exchange from my seat in the gallery, I wonder what shorthand Judge Cannon would use instead of “regulatory special counsel.” In my view, “special counsel operating under regulations promulgated by the attorney general pursuant to his statutory authority under 28 U.S.C. § 515 and 28 U.S.C. § 533, etc.” just doesn’t have the same ring to it.

Moving on, Judge Cannon asks Pearce what he has to say to Bove’s suggestion that there is an “inherent tension” between the government’s arguments on the Appointments Clause and its arguments regarding the appropriations issue.

I think it’s a tension that affects “both sides,” Pearce says. Citing an article written by Brett Kavanaugh before he joined the Supreme Court, Pearce explains that there has long been an inherent tension in striking the balance between accountability and independence for special counsels. Balancing the need for independence without giving a special counsel “free reign” is the concern that ultimately led to the lapse of the independent counsel law, he says.

Now Judge Cannon announces that she has a quick “case law follow-up” regarding the Appointments Clause issue. “Are you familiar or aware of any circuit case law addressing whether a U.S. attorney is a superior or inferior officer?”

Pearce tells the judge about a Supreme Court case, Myers v. United States, in which the Court says that some version of a “district attorney”—at that time, something like a modern U.S. attorney—is an inferior officer. Additionally, Pearce notes a First Circuit case called United States v. Hilario and a Ninth Circuit case called United States v. Gant.

Judge Cannon wonders aloud what she should make of the various statutes that require, for example, U.S. attorneys and the solicitor general to go through the presidential nomination and Senate confirmation process. What to make of that statutory congressional judgment for such high-level individuals? she asks.

That’s Congress playing an oversight role that it is entitled to do, Pearce says. In the Federalist Papers, he continues, Alexander Hamilton discusses how that kind of process can “produce better officers.” Congress could be of the view that requiring an officer to go through the confirmation process produces better-quality officers, he says. “But that doesn’t transform it into a constitutional requirement; it is statutory.”

There has been some discussion about “congressional acquiescence,” Judge Cannon observes. The idea, she explains, is that congressional judgments can serve as a dispositive signal about the constitutional status of an officer. And Congress has repeatedly subjected certain positions to a confirmation process, she continues. Would we then reach the inference that someone tantamount to that position would also, necessarily, have to go through that same procedure?

That isn’t the test for whether an officer is a principal or inferior officer, Pearce responds. He then reiterates that Congress could believe that subjecting individuals to the confirmation process leads to “better quality” officers. But ultimately, he concludes, that doesn’t define the scope of the constitutional question.

That’s all I have, Judge Cannon announces. “Thank you, Mr. Pearce.”

Bove paces to the lectern to deliver a rebuttal on behalf of Trump. Addressing the issue of the appropriate remedy, he first directs Judge Cannon’s attention to the concurring opinion of Judge Edith Jones in a case from the Fifth Circuit, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. All American Check Cashing, Inc. In that concurrence, Bove says, Judge Jones walks through “all of the different types of ways” that a separation of powers problem can bear on what the appropriate remedy is.

The Supreme Court didn’t have the occasion to address the appropriate remedy in the CFPB case, according to Bove. Here, we have a very different situation than what happened in CFPB, he asserts. This case involves a very specific special counsel taking actions against a defendant who is “very much aggrieved” by the imminent threat to his liberty. And the type of relief we are seeking—dismissal—is appropriate based on what Judge Jones said in All American Check Cashing, he says.

Bove then turns to the government’s argument that it could rely on an alternative appropriation to fund Trump’s prosecution. “It's difficult for me to imagine how that is a basis to resolve this motion, and I think what it really does is highlight the separation of powers issues that we’re talking about,” he says. The Special Counsel’s Office should not be able to say, hypothetically, that there are other appropriations that they may be able to access, Bove complains. He continues: I think there would be a “very strong political response” if the Justice Department decided to use an alternative appropriation. Congress would have a response, and we might have to file another motion, he warns.

Lastly, Bove acknowledges that Judge Cannon asked about the “inherent tension” between the arguments he put forward on Friday and the arguments he made today regarding the special counsel’s degree of independence. Our position, he claims, is that more oversight from Congress is required for the “extraordinary things” that are going on in this prosecution. According to Bove, that could mean oversight on the front end, as contemplated for principal officers, or it could be based on a real appropriations process. The government’s position, by contrast, is that “much less” is required—and that is a “disrespectful and unacceptable” way to deal with the separation of powers issues implicated here, Bove concludes.

Thank you, Judge Cannon says once Bove wraps up. That will conclude our arguments this morning on the motion to dismiss, she announces. She adds that court will resume at 3 p.m. to discuss the bond modification motion. “I wish you all a pleasant lunch,” Judge Cannon says before she departs.

* * *

After lunch, the parties are back in Judge Cannon’s courtroom for a hearing on the government’s motion to modify Trump’s bond conditions.

The Special Counsel’s Office filed the motion last month, after Trump claimed in a social media post that “Crooked Joe Biden’s DOJ” had “AUTHORIZED THE FBI TO USE DEADLY (LETHAL) FORCE” during the court-authorized search at Mar-a-Lago in August 2022. That same week, Trump made similar public statements in which he asserted that law enforcement “WAS AUTHORIZED TO SHOOT ME” and that agents involved in the search were “locked & loaded ready to take me out & put my family in danger.”

Citing those statements as well as other “false” or “misleading” remarks, the special counsel’s motion argues that Trump’s rhetoric exposes law enforcement witnesses to “risk of threats, violence, and harassment.” As such, the government wants Judge Cannon to modify Trump’s conditions of release to prohibit him from making statements that pose a “significant, imminent, and foreseeable danger to law enforcement agents participating in the investigation and prosecution of this case.”

Trump’s legal team opposes the motion, calling it a “naked effort to impose totalitarian censorship.”

Now, as a court officer brings us to order at 3:00 p.m., Judge Cannon takes her seat at the bench to conduct a hearing on the matter.

Directing her attention to the table where prosecutors representing the Special Counsel’s Office are seated, Judge Cannon asks who will be taking the lead on arguing the motion.

In reply, Jay Bratt announces that his colleague, David Harbach, will argue the motion. But before he does so, Bratt says that Pearce would like to correct a representation he made during his argument this morning. The judge allows it, and Pearce strides to the lectern.

Briefly, Pearce reminds Judge Cannon that she asked some questions about the special counsel’s expenditure report. Pearce continues: “To the extent that I said or suggested that attorneys working at the Special Counsel’s Office on detail from other components of the Justice Department were paid by their home components, that was not accurate.” They are paid by the permanent indefinite appropriation.

With that correction in the record, Pearce turns the floor over to Harbach.

Before Harbach begins his argument, however, Judge Cannon wants to know if the Special Counsel’s Office wishes to “supplement the record on the motion.” Harbach replies that there are a couple Truth Social posts he may bring to her attention during his argument today that were not cited in prior briefing.

Well, for me to make any use of additional material, I would have to see it physically, Judge Cannon replies. And, presumably, you have made those posts available to the other side, she says. “But as far as I’m concerned, I’m operating off of the record as it exists today, and I haven’t heard any motion for either live witness testimony or supplementation of the record.”

Harbach proceeds to the substance of his argument. “The Special Counsel’s Office filed this motion to modify Mr. Trump’s bail conditions for one purpose only, only one; and that is to protect law enforcement witnesses who are involved in this particular case,” he begins.

Judge Cannon asks Harbach to clarify the “legal framework” for the motion.

Harbach, in response, explains that there are two “sources of authority” under which Judge Cannon could amend Trump’s bail conditions. The first is the Bail Reform Act, which permits modification of Trump’s conditions to “reasonably assure … the safety of any other person or the community.” The second, Harbach says, is the court’s “inherent authority” to protect the integrity of the proceedings.

If the court grants the requested relief under the Bail Reform Act, Harbach says, then that would “necessarily eliminate” any First Amendment concerns that would be a part of the court’s analysis if it were to amend Trump’s conditions under its “inherent authority.” The reason why, Harbach explains, is that under the Bail Reform Act the court would have to find that the condition is “reasonably necessary” to assure the safety of the community. And that would take it out “of the land of First Amendment Concern,” according to Harbach.

Judge Cannon doesn’t sound convinced. Do you have any case law that proceeds in the way you have just described? In other words, by virtue of a finding of reasonable necessity, your First Amendment concerns, at least some of them, fall away?

Well, no, Harbach replies. But I will tell you what we haven’t found: A case where a court has conducted a First Amendment analysis after finding that a restriction on speech is “reasonably necessary” to assure the safety of the community. That’s consistent with our view that a separate First Amendment analysis wouldn’t be necessary.

Having clarified the “legal framework,” Harbach returns to the substance of his argument. “I think we can all agree—or we should be able to all agree—that defendants in criminal cases should not be permitted to make statements that pose a significant, imminent, and foreseeable danger to any witnesses in the case,” he says.

Here, Harbach continues, the court must decide whether the condition the government proposed is reasonably necessary. And to that end, “I think it’s important to point out that we’re not operating on a blank slate here.” He emphasizes that “every court” that has examined this question has “recognized the threat” caused by the long-standing and well-documented dynamic between Trump’s comments, particularly on social media, and the predictable response from some of his supporters. Harbach then cites, by way of example, an attack in Cleveland, Ohio, which occurred in the wake of the Aug. 8, 2022, search of Mar-a-Lago.

Judge Cannon interjects: Just so I understand, all the names of law enforcement witnesses in this case are redacted in public court filings, correct?

Harbach replies that yes, the names should be redacted pursuant to prior orders issued by Judge Cannon.

The Bail Reform Act requires me to look at the “least restrictive” conditions, Judge Cannon notes. If those names have been shielded from public view, shouldn’t that be a consideration in trying to determine whether their safety could be harmed? she asks.

That is true, Harbach says, but there are a few reasons why it should not “remotely” carry the day. For one thing, he tells the judge, there are a small number of agents whose names are already public. They were “doxxed” publicly, multiple times, in the wake of the execution of the search warrant.

Judge Cannon can’t understand how that’s relevant. Okay, she says, but this motion was brought on the basis of statement that the defendant made in May of 2024. So how far back do you submit we should go to determine whether you’ve made your evidentiary showing? Because what you’ve just said relates to the potential release of agent names in 2022.

Harbach stresses that the timing of when the agents were doxxed is immaterial for this part of the analysis. The point is that the names are out there, he says.

“But there still needs to be a connection between the alleged dangerous comments and risk to safety,” Judge Cannon says.

Then the judge asks Harbach if he knows how the names of agents involved in the search “got released.” And do you have any evidence to suggest that it was caused by any of the defendants in this case or any other “defense participants”?

Harbach hesitates before he responds. “My only hesitation,” he explains, “is the prospect that this person might be a defense witness.” We do know the identity of the person who did this, he says, and it was “definitely” not the defendants or their lawyers. But agents or associates or—

Judge Cannon cuts him off: “Well, if that’s the case, there are legal means, presumably, to address doxxing.” So, she wonders aloud, why would that carry over to an analysis about whether a bail modification is warranted at this juncture?

Harbach tries to explain that he only brought up the doxxing issue in response to Judge Cannon’s suggestion that the fact that agent names have been redacted means that there is no need for a bail condition modification. And I’m trying to explain why the fact of redaction is not a “least restrictive means” that “remotely” accomplishes the objective of assuring safety, he says.

Harbach and Judge Cannon have been talking past one another throughout the former’s argument. And Harbach, at this point, sounds exasperated.

“Mr. Harbach, I don’t appreciate your tone,” Judge Cannon snaps. “I think we’ve been here before, and I would expect decorum in this courtroom at all times,” she says. “If you’re unable to do that, then I’m sure one of your colleagues can take up this motion.”

Yes, Your Honor, Harbach replies.

Moving on, Harbach tells Judge Cannon that there’s a “there’s a reason we sought this relief when we did.” It was a result of Trump’s statements during the week of May 21, 2024, he says. Then: “In our view, they are significant. They are dangerous. They present an imminent and foreseeable danger to the FBI witnesses in this case, and it will not suffice to say that, if their names come out at trial, we will at that point seek some other means to protect them.”

Now Judge Cannon turns back to the issue she raised earlier regarding the First Amendment analysis. Harbach contends that a First Amendment analysis is not necessary for speech that is curtailed because it is “reasonably necessary” to protect the safety of the community. But Judge Cannon isn’t so sure.

“That's a little bit different than incitement to violence, calls for violence, true threats…the sort of traditional core, unprotected speech,” she says. She wants to make sure that “we’re not falling too far away from those traditional categories as described by courts.”

Harbach replies that Trump is a criminal defendant whose rights are more limited than the average citizen’s. Then, turning to the specific statements made by Trump during the week of May 21, he says that “the government is at a loss to conceive of any possible reason why Mr. Trump would suggest something so flagrantly false, inflammatory, and inviting of retributive violence.”

Judge Cannon, for her part, wants to know what “evidence” Harbach has to suggest that violence has been threatened or resulted from these statements.

For one thing, Harbach replies, these statements weren’t made in a vacuum. The statements were made in a context that “every court” to consider it has concluded exists. “Namely, that the statements that Mr. Trump puts out on social media are read, digested, and ultimately result in all sorts of terrible things, threats, violence, and so forth,” he says. What’s more, Harbach continues, Trump “knows it.”

Before Harbach wraps up, he addresses whether the requested modification is the “least restrictive” condition to protect safety. In arguing that it is the least restrictive alternative, Harbach says that the judge presiding over Trump’s federal case in D.C. warned the parties about speech that would affect the integrity of the proceedings. That didn’t work, he stresses, which resulted in the necessity of instituting the gag order in that case in the first place. “So we think Your Honor could certainly take something from that in thinking about least restrictive alternatives,” he says.

Harbach is done, but before he goes, he offers an apology to Judge Cannon. “I just want to apologize about earlier. I didn't mean to be unprofessional. I’m sorry about that,” he says.

Now Todd Blanche is at the lectern to argue on behalf of Trump. If you look at the public statements cited by the government, Blanche says, there is no “actual connection” between those statements and a “significant, imminent, and foreseeable danger to law enforcement.” These attacks are “very clearly” against President Biden, according to Blanche. And if you look at the actual posts, there is no threat to FBI agents and there is no incitement to violence, he emphasizes.

There is much discussed about the fact that they were armed, and whether that’s normal or typical or standard practice, Blanche continues. It is true it is standard practice, he admits, “but that doesn’t mean that it was right.” As Blanche tells it, Trump still has the right to raise his hand and say: “I was the President of the United States. You raided Mar-a-Lago. It’s protected by the United States Secret Service agents with guns. Why did you do this? Why didn’t you make a different decision and not go in armed?”

Judge Cannon asks if Blanche thinks a separate First Amendment analysis is necessary in the context of the Bail Reform Act.

The analysis necessarily includes a First Amendment analysis, Blanche replies. Further, he says, in determining whether the modification is “reasonably necessary,” it matters that the names of law enforcement witnesses have been redacted. And while it is true that some of the witnesses associated with the search at Mar-a-Lago may testify at trial, “courts are perfectly suited to handle those issues along the way.” So, for that reason, it’s not an “imminent” or “foreseeable” danger, Blanche contends. He adds that there is “absolutely” no evidence of a connection between Trump’s statements and FBI agents “supposedly” having their life at risk.

President Trump has “no desire” for anything bad to ever happen to law enforcement, Blanche asserts. The fact that there were agents who were doxxed is “horrible.” But the doxxing cannot be used by the court to impose this new condition, he says. Blanche then notes that there are “ways to deal with people that are doing things like that,” including a “whole host” of criminal statutes that criminalize threats and harassment.

Blanche reminds Judge Cannon that Trump is running for president. The voters of this country have a “right” to listen to what he says, according to Blanche. And he should not have a condition imposed that would allow his bail to be revoked for saying something true: that “Biden’s DOJ authorized deadly force against President Trump” during the “Mar-a-Lago raid.” Under this new bail condition, Blanche says, if the special counsel believes that Trump says something that violates that condition during the upcoming presidential debate, then the special counsel could “go to a judge in Atlanta and get an arrest warrant for President Trump.” And it could happen “ex parte,” so “potentially we wouldn’t even know that it was happening.”

Finally, Blanche touches on what he calls the “vagueness” of the proposed condition. The special counsel has labeled it as “narrowly tailored,” but that’s simply “not true,” Blanche complains. It would be “extremely chilling” on Trump’s speech, he says, and simply limiting it to law enforcement witnesses doesn’t help because there are “a lot” of law enforcement officials involved in this prosecution.

Blanche is done, and Harbach pops up from his seat to deliver rebuttal on behalf of the Special Counsel’s Office. First, he says, there would be no “chilling” effect on Trump’s political speech because statements that fall under the proposed condition could not properly be termed “campaign speech.”

Next, Harbach addresses Blanche’s argument that there is no “causal link” between Trump’s statements and violence or threats against law enforcement. “You don’t have to wait for something terrible to happen in order to impose a condition like this,” he tells Judge Cannon.

Harbach wraps up and returns to his seat at the counsel’s table. Judge Cannon, for her part, announces that she will allow the parties to file supplemental evidence in support of the motion until June 26.

“That concludes our argument on this motion,” Judge Cannon announces.

June 25, 2024

It’s almost 11:00 a.m. in Fort Pierce, Florida, the following day, and the parties in United States v. Trump are back in court for another hearing before Judge Aileen Cannon.

Today, two hearings are scheduled on Trump’s “Motion for Relief Relating to the Mar-a-Lago Raid and Unlawful Piercing of Attorney-Client Privilege.” The first session—on Trump’s effort to suppress the notes of his former attorney, Evan Corcoran—is closed to the public and the press. The second session—on Trump’s challenges to the validity of the warrant that authorized the August 2022 search at Mar-a-Lago—is set to commence later this afternoon.

All of which is why, as the first hearing kicks off in Judge Cannon’s air-conditioned courtroom, the journalists are standing outside the courthouse, baking under the Florida sun.

By 1:00 p.m., the journalists—some of us still glistening with sweat—have rejoined the parties in Judge Cannon’s courtroom for the public portion of today’s proceedings. The judge, seated behind the bench, announces that she will now hear arguments on the remaining aspects of Trump’s motion.

Those “remaining aspects” on the agenda relate to Trump’s effort to suppress evidence or dismiss his charges based on alleged defects in the warrant application or the warrant itself. With respect to the latter, Trump claims that language contained in the warrant does not satisfy the Fourth Amendment’s requirement that it describe with particularity the place to be searched and the items to be seized. With respect to the former, Trump’s motion argues that an affidavit filed in support of the warrant application contains omissions or misrepresentations that could have affected the magistrate judge’s probable cause determination. To substantiate those claims, the motion requests a “Franks hearing”—that is, an evidentiary hearing during which Trump’s defense counsel could question law enforcement witnesses or present evidence to support the contention that the warrant should not have been issued.

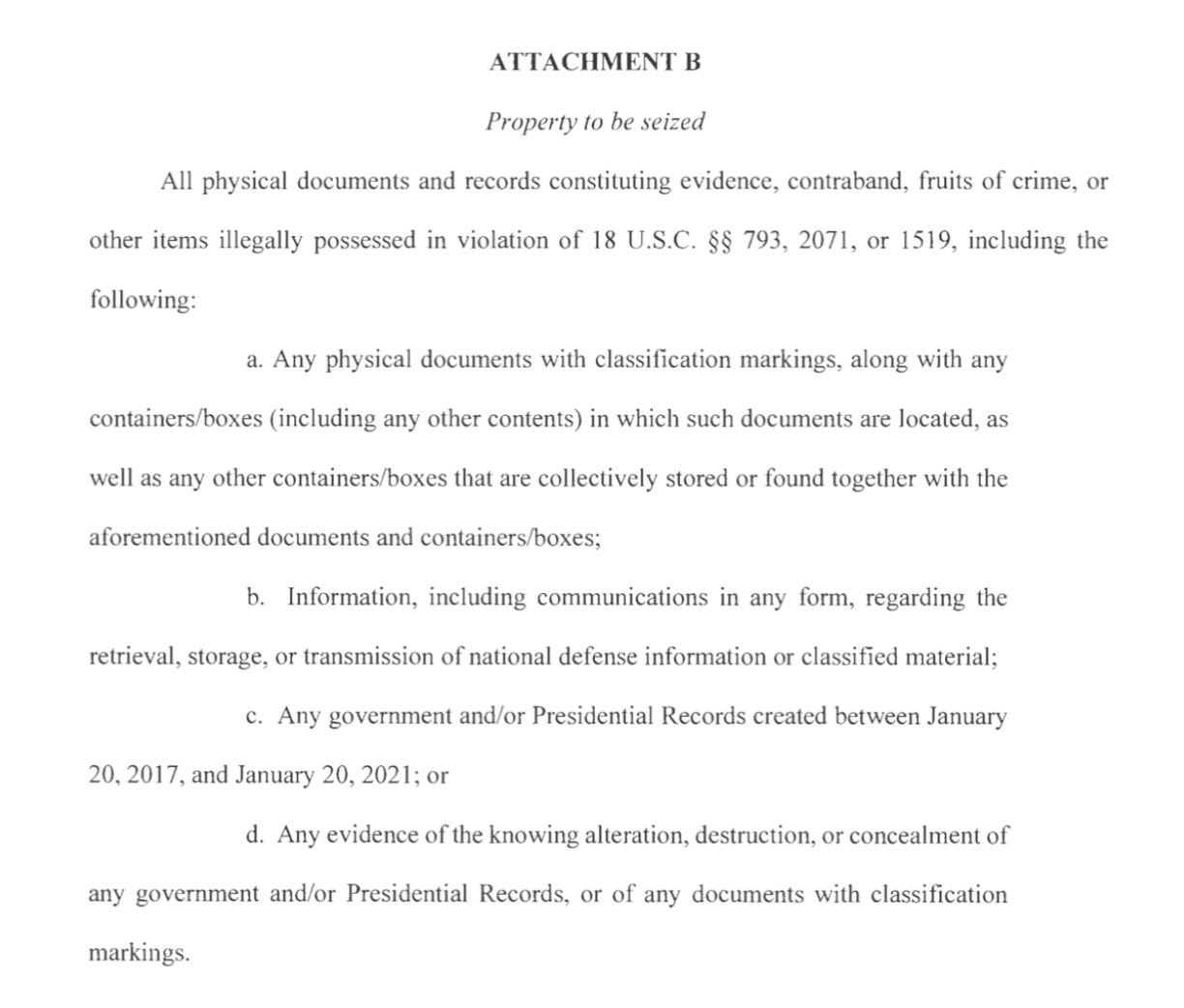

All of which brings Bove to the lectern to argue the motion on behalf of Trump. He kicks things off by addressing Trump’s argument that the warrant is not sufficiently particular. The first defect is contained in Attachment B of the warrant, which describes the property to be seized.

During our prior civil litigation before this court, Bove says, Your Honor found that the agents who executed the warrant used Attachment B to seize “personal effects” without evidentiary value. Why did that happen? he wonders aloud. I think part of the reason, he continues, is that the warrant itself didn’t provide sufficient specificity with respect to what could be seized. And “that starts with the introductory language of Attachment B,” which authorized the seizure of “all evidence” of certain statutory violations. But the warrant itself did not describe or summarize those statutes in any way, Bove claims.

What more needed to be contained in Attachment B? Judge Cannon asks.

Bove replies that the warrant sh0uld have included descriptions of what it means to violate the enumerated statutes or “non-legalese” language the agents could use that offers some guidance.

Judge Cannon doesn’t sound convinced. Why isn’t it enough that subsection (a) says “any physical documents with classification markings?”

That’s not a restriction on the introductory language I’m discussing, Bove responds.

“Right, but it has to be read in context,” Judge Cannon observes.

Moving on, Bove argues that it was “inappropriate” to include language referring to “national defense information” in Attachment B.

Judge Cannon wonders aloud why that would be “inappropriate.” I mean, it’s a “critical term in the decisional law” for the relevant statute under which Trump is now charged, she says.

But the term “national defense information” is “virtually contentless” on its face, Bove replies. And the government felt that it was necessary to define that term in the warrant application, yet it wasn’t defined in the warrant for the searching agents, he says.

Do you have any case law suggesting that for the purpose of itemizing property to be seized a warrant must include the equivalent, essentially, of a “legal brief” that describes each essential element of an offense? Judge Cannon queries.

No, but that’s not our argument, either. It doesn’t need to be “element by element,” but some guidance is necessary. And our position is that “national defense information” should not have been included because it doesn’t provide sufficient guidance to the agents who participated in the search.

Next, Bove contends that another phrase in Attachment B—"government and/or Presidential Records”—is “overly broad.” These terms are ambiguous, Bove argues. And it’s again an instance in which the government felt compelled to provide definitions for the magistrate in the warrant application, but the searching agents were not similarly provided with that guidance.

Judge Cannon follows up: Were the agents who participated in the search directed to review the full affidavit prior to executing the search?

“I think that’s a fact question that requires a hearing, judge. It’s not something that can be resolved on the face of these papers.”

I think there’s some reference to that in the operational plan developed by the FBI prior to the search, Judge Cannon notes.

Bove concedes that there is some reference to that in the operational plan. “But that’s a document about what people contemplated beforehand,” he says. Bove thinks that whether the agents actually followed that instruction is a disputed fact that would have to be established at a hearing.

Focusing specifically on the term “presidential records,” Bove asserts that there are “complexities” associated with this term—complexities that FBI agents executing a search at a former President’s home are in “no position” to assess. He points out, for example, that the definition of “presidential records” under 44 U.S.C. § 2201 excludes extra copies of documents. Based on that exclusion, the presidential records” is not one that the agents who conducted the search could apply “on the fly” simply by looking at a document.

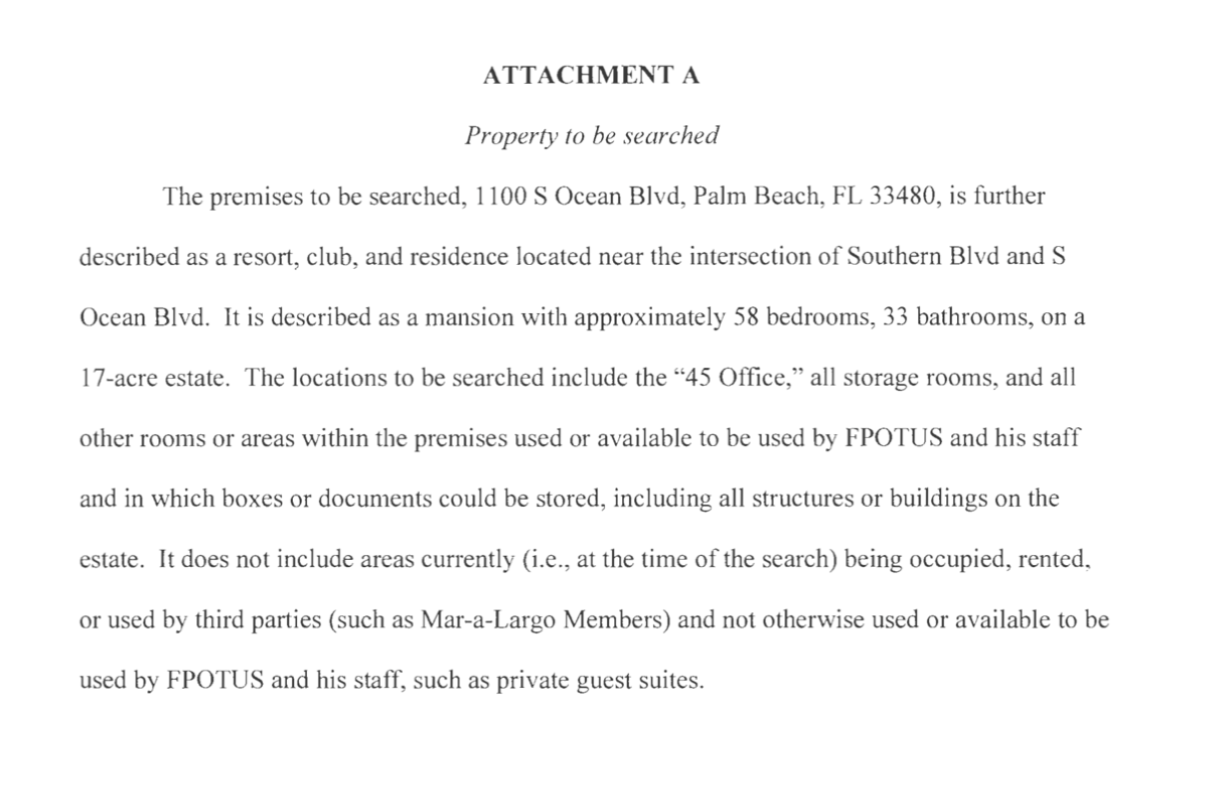

Bove then turns to Attachment A, which is the part of the warrant that describes the places to be searched.

“Taking a look at the warrant application, we think that it established probable cause with respect to the six locations that we identified in our brief,” he says. He lists the six locations: the White and Gold Ballroom, the storage room, the anteroom to the storage room, “the President’s residential suite,” Pine Hall, and Trump’s office. “At most,” Bove stresses, the search warrant application established probable cause to search only these areas. But Attachment A, he explains, conferred an “unacceptable amount of discretion” on the agents with respect to the areas to be searched. The area to be searched as described in the attachment includes rooms, for example, that are “used or available to be used by FPOTUS and his staff.”

The Fourth Amendment, Bove stresses, requires that agents not be permitted to go “rummaging.” And that is “the issue here” when you look at Attachment A, which “authorizes a search of the entire property when the application only speaks to specific areas.”

To illustrate his allegation that agents went “rummaging” through Mar-a-Lago, Bove claims that the agents “searched and photographed the First Lady’s bedroom.” And they searched the bedroom of the president’s youngest son, he says. “They purported to look for classified documents in a gym and in a kitchen,” Bove complains.

Were any items recovered from those locations? the judge inquires.

Not to my knowledge, Bove responds.

Judge Cannon: So what’s the prejudice if no evidence was seized as result?

“The legal claim is that there was an impermissibly broad search that hit rooms all over Mar-a-Lago that there was not probable cause to search, and that the overbreadth of that search violated President Trump's rights,” Bove explains. And there are “factual questions” about the scope and manner of the search that bear on the suppression remedy, he adds.

Judge Cannon: You would agree that the paperwork, though, is a sort of thing that can be located anywhere?

Generally speaking, yes, Bove concedes. But here, there was “no evidence” that someone had stored documents bearing classification markings in the room “where the president’s son kept his Peloton bike.”

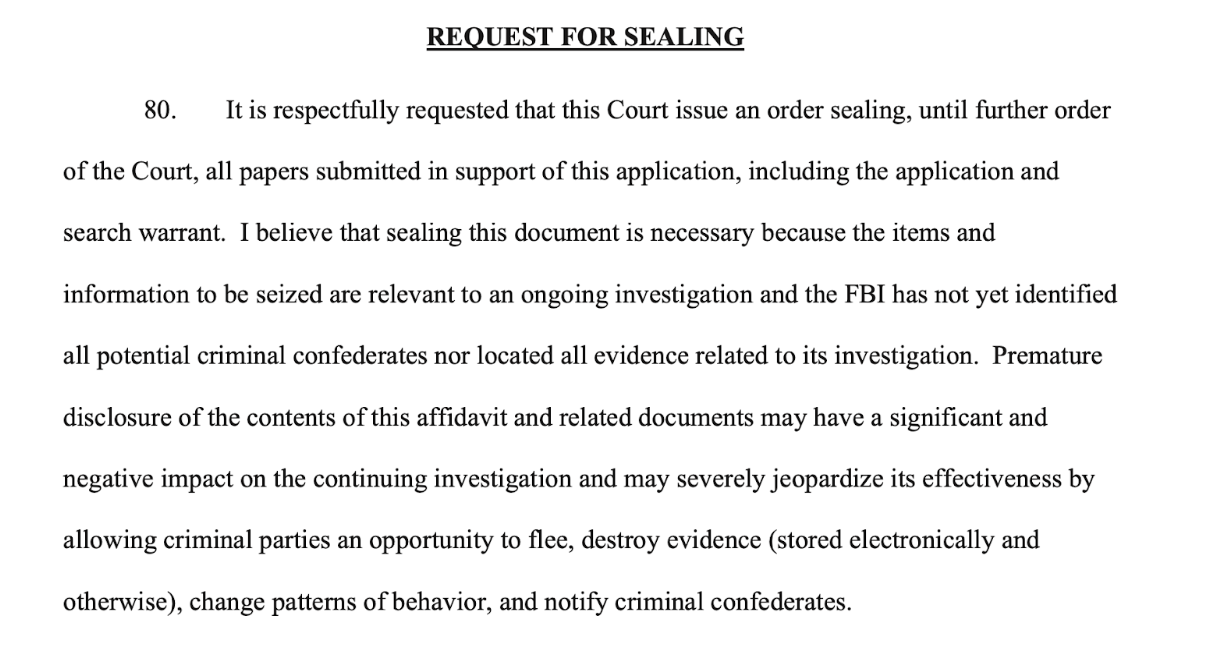

Bove next addresses Trump’s request for a Franks hearing. We have identified a series of omissions and misrepresentations in the affidavit that was filed with the warrant application, he says. We think that those misrepresentations or omissions would have affected the probable cause determination and that a hearing is necessary to look at the mental state of the agents, he explains.

Turning to the content of the alleged misrepresentations or omissions, Bove says that there is “some evidence” that FBI personnel did not think that a search pursuant to a warrant was necessary and that it was inconsistent with historical practice. He points to congressional testimony of a retired FBI agent, Steven D’Antuono, who at the time of the search was the assistant director in charge at the Washington field office. D’Antuono’s testimony shows that at least some FBI personnel were of the view that a consent search, as opposed to a search pursuant to a warrant, would have been the preferable course of action.

Judge Cannon interjects: But why would that matter legally?

In Bove’s view, it matters because in paragraph 80 of the supporting affidavit the affiant swore that premature disclosure of the materials related to the warrant application would have a “significant negative impact” on the continuing investigation. But D’Antuono’s testimony shows that there’s a “factual dispute” about whether that statement was accurate.

But this paragraph of the affidavit concerns a request to seal the warrant materials, Judge Cannon observes. Does that really go to the probable cause determination?

“They made representations in this affidavit about whether or not it was safe to be storing the types of documents that they allege existed at Mar-a-Lago under those circumstances,” Bove replies. And so a representation about risks to destruction of evidence and flight is relevant to what the judge is considering, he says.

Bove pivots to the alleged “omissions” in the affidavit. The affidavit does not mention, first, that the president of the United States is not required to maintain security clearance, he says. And, second, it omits the fact that Trump, while he was in office, received classified security briefings at Mar-a-Lago.

Judge Cannon pushes back on this: But how would that have changed anything? She notes that the government’s theory is that Trump retained classified documents post-presidency. “The key is post-presidency,” she says.

Bove, for his part, argues that Trump’s ability to receive classified materials and briefings during his presidency bears on the question of intent post-presidency. That’s why it should have been included in the affidavit, he says.

The next omission, Bove says, has some “overlap” with the argument he earlier presented on the particularity requirement. He points out that the affidavit omits the “decisional case law” related to the Presidential Records Act—namely, case law related to the president’s discretion to identify and designate presidential versus personal records.

Why do you think that would have made a difference in the probable cause determination? Judge Cannon asks.

Because the magistrate judge would have understood that the president is able to designate records as personal and, understanding that, would not have authorized agents to go into Mar-a-Lago to seize purported presidential records.

“Even if they bore classification markings?” Judge Cannon queries.

I think that could be a different argument, Bove replies. But agents seized pieces of paper “anywhere near” a document bearing classification markings. And so that is part of our argument about why this search was executed in an unconstitutional way, he says.

Taken together, Bove says that the omissions and misrepresentation he has detailed during his argument warrant fact-finding by way of a Franks hearing. It appears that he is done, and Judge Cannon says that she’ll hear from the Special Counsel’s Office next. But Bove says he wants to address one further issue: The “good-faith” exception to the exclusionary rule. He’s referring to the idea that, even if Judge Cannon finds that alleged flaws in the warrant materials violated the Fourth Amendment, evidence obtained as a result of the search will not be suppressed if law enforcement had a reasonable, good-faith basis to rely on the warrant.

Citing the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Leon, Bove says that the good-faith analysis in this case requires fact-finding of some sort. Leon, he says, mentions that “all of the circumstances” may be taken into account in evaluating the application of the good-faith exception. What more, he continues, the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Herring states that those circumstances frequently include an officer’s “knowledge and experience.”

Bove goes on to argue that “knowledge and experience” of the searching agents is “very relevant” here because they were asked to apply terms like “national defense information.” Our view, Bove contends, is that “one way or another” the government has an obligation to conduct a reasonable search, whether that’s through training and experience in the national security space, the instructions given to the searching agents, or the face of the warrant itself.

Judge Cannon doesn’t sound impressed with this argument. “It just seems like you’re making policy arguments about training and experience, and it seems far afield from the legal inquiry whether the affidavit itself contained the essential elements to meet the probable cause standard,” she responds. “I’m unclear as far as what you think should have been included in the affidavit or what was in there that shouldn’t have been in there from a good-faith perspective.”

Bove tries to clarify: The point, he says, is that there are “all kinds of things that bear on the manner in which this search was executed.” These factual disputes have to be “resolved,” he says, before the court could find that the exclusionary rule doesn’t apply under Leon. The government can’t ask you to look past the Fourth Amendment issues we’ve talked about and ask you to apply Leon without a hearing, he urges. And it’s their showing to make, he concludes.

With that, Bove is done. Now it’s David Harbach’s turn to deliver a rebuttal on behalf of the Special Counsel’s Office.

Harbach first addresses the latter part of Bove’s argument. He tells Judge Cannon that Bove’s argument “conflated” the necessity of a hearing under “the Franks rubric” and the necessity of a hearing under the Leon good-faith requirement. Those are “separate silos,” according to Harbach.

Focusing on what’s required under the Franks framework, Harbach reminds Judge Cannon that a defendant must “make a substantial preliminary showing that the affiant made false statements” and, furthermore, “that the affiant did so either intentionally or with reckless disregard for the truth.” He adds that the defendant must also show that, absent these misrepresentations or omissions, probable cause would have been lacking. So, Harbach stresses, it’s not a question of “good faith.”

Harbach turns to the substance of the alleged misrepresentations or omissions cited by Bove. As Your Honor already pointed out, Harbach says, the alleged misrepresentation in paragraph 80 appears in the section of the affidavit related to the government’s request to seal the documents. In our view, he continues, this “utterly undercuts” the notion that this had anything to do with probable cause.

Next, Harbach addresses the “omissions” related to Trump’s ability to receive classified briefings without security clearance during his presidency. He explains that at the time the search warrant application was made, the government included a letter from one of Trump’s attorneys in the application packet. The letter, he says, articulated various theories, including theories regarding the president’s authority to declassify.

This matters because the inclusion of that letter in the application before the magistrate judge is inconsistent with the idea that the affiant intended to mislead the court, Harbach contends. And the text of the search warrant actually mentions this letter, he says, so “there is no way that they could make their required showing about intent to deceive or reckless disregard for the truth.”

What’s more, Harbach continues, whatever authorization Trump had as president doesn’t matter because the conduct was post-presidency. For that reason, it doesn’t affect the probable cause analysis.

Regarding the omission of the definition of personal records under the Presidential Records Act, Harbach again cites the letter from Trump’s counsel that the government included in the warrant application packet. According to Harbach, Trump’s counsel in that letter did not make the argument that the Presidential Records Act operated in a way that authorized the president to retain classified information. That proves the point that Trump did not come up with this defense until more than a year and a half later, he says.

Moving on to the particularity requirement, Harbach points out that Bove seemed to concede that the warrant established probable cause to search Mar-a-Lago in six areas. But the warrant plainly doesn’t limit the search to those six areas, he says. And that was “particularly appropriate here” because “it’s a big property” and the items the agents were looking for—papers, documents—”are quite small.”

It’s true that the face of the warrant set limits on the breadth of the search, Harbach acknowledges. It did not, for example, allow agents to go into places that Trump didn’t have access to. But “Mr. Trump did have access to his wife’s quarters, to his son’s quarters.” For that reason, Harbach contends, there was “nothing remotely inappropriate about the agents searching those places.”

Judge Cannon interjects: Was there any evidence to suggest that documents with classified markings would have been located in the bedroom of the former president’s child? Or was there any evidence to suggest that the boxes moved to the child’s room?

No, no direct evidence of that, Harbach replies. But we know the boxes moved. “I mean, at one point the boxes were in a shower in a bathroom.” Harbach adds that nothing was seized from that location. But, he says, it would have been “irresponsible” for the agents not to search there given that it was plainly within the scope of the warrant.

Judge Cannon follows up by asking Harbach to clarify where information with classification markings was ultimately found. He replies that they were found in two locations: the storage room and the former president’s office.

Continuing his argument on the particularity requirement, Harbach pivots to Bove’s argument that the statute did not provide sufficient guidance on statutory terms like “presidential records” or “national defense information.” “It cant be that a search warrant is required to include, you know, a legal brief or a mini dissertation about the elements of offenses in order to make a warrant sufficiently particular,” Harbach tells Judge Cannon.

Finally, Harbach discusses the applicability of the good-faith exception and the extent to which an evidentiary hearing is required under Leon. Even if the court were to conclude that the warrant is not sufficiently particular, he says, then the question is whether the warrant was “so facially deficient that the executing officers cannot reasonably presume it to be valid.”

And while Trump argues that the FBI conducted the search in an “egregious fashion,” Harbach claims that there was nothing egregious about it. Further, he says, Trump cannot assert that there was “politically motivated animus” behind the search as a way to justify an evidentiary hearing. Citing the Supreme Court’s decision in Herring, he notes that the legal analysis under the good-faith exception is an objective one. It’s not an inquiry into a law enforcement officer’s subjective intent. So ultimately, Harbach concludes, Trump’s claims regarding the manner of the search of the allegations of animus do not bear on the question before the court, which is whether the language in the warrant satisfies the particularity requirement.

Judge Cannon thanks Harbach, who returns to his seat. Bove strides back to the lectern to offer a few points in response.

He clarifies that Trump “does not concede” that there was probable cause for the six areas at Mar-a-Lago he mentioned earlier. “My point is just that, with respect to those locations, there is at least references to them in the warrant application.”

Next, Bove notes that Harbach said there was nothing “egregious” about the manner in which the search was conducted. But the fact that Trump has put forward evidence that is “in tension” with that assertion requires a hearing, he contends. And Bove complains that the government has not been “straightforward” with Judge Cannon about whether and to what extent communications exist between FBI agents that might reflect political animus. That would be relevant to the good-faith exception, he argues.

Judge Cannon pushes back: Your challenge is a particularity challenge, she says, which means I look at the affidavit and determine if it’s particular enough. “And it seems like it is, based on the case law that’s been submitted.” I have a hard time seeing what more language needed to be included in either attachment A or B, she tells Bove.

Bove is done, and Judge Cannon is clearly ready to wrap up at this point. But Harbach, not willing to let Bove have the last word, asks the judge if he can briefly respond. Judge Cannon says she’ll give him “30 seconds.”

Harbach, who is clearly frustrated, addresses Bove’s claim that “political animus” is relevant to the application of the good-faith exception. The Herring case, he reminds the judge, sets out an objective test. And it’s not “just some case law.” It’s an opinion of the Supreme Court authored by a chief justice of the United States—

Before he can finish his sentence, Judge Cannon cuts him off. “I don’t want to get into this sort of tit-for-tat thing. I understand it’s an objective test.”

Harbach moves on. The last thing I would like to say is about the defense’s effort to “hijack” this hearing, he begins.

Again, Judge Cannon cuts him off: “There’s no hijacking going on.” Do you have any legal authority you’d like to discuss?

Harbach, undeterred, says that he has a “factual point” he’d like to raise about the “tactics” of the defense.

What does it concern? Judge Cannon says hesitantly.

“It concerns the defense’s repeated attempts to use hearings like this to import allegations that have nothing to do with what is before the court.”

Harbach starts to say something else, but the judge has heard enough. All right, let’s conclude, she says.

Harbach is undeterred: “It’s not fair,” he practically shouts.

“I will be concluding this hearing,” Judge Cannon repeats. “The motion is taken under advisement,” she announces before she hurriedly retreats to her chambers.