The Fourth Quadrant—the Unknown Knowns

Unknown knowns pose the most difficult problems for people and nations to address.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

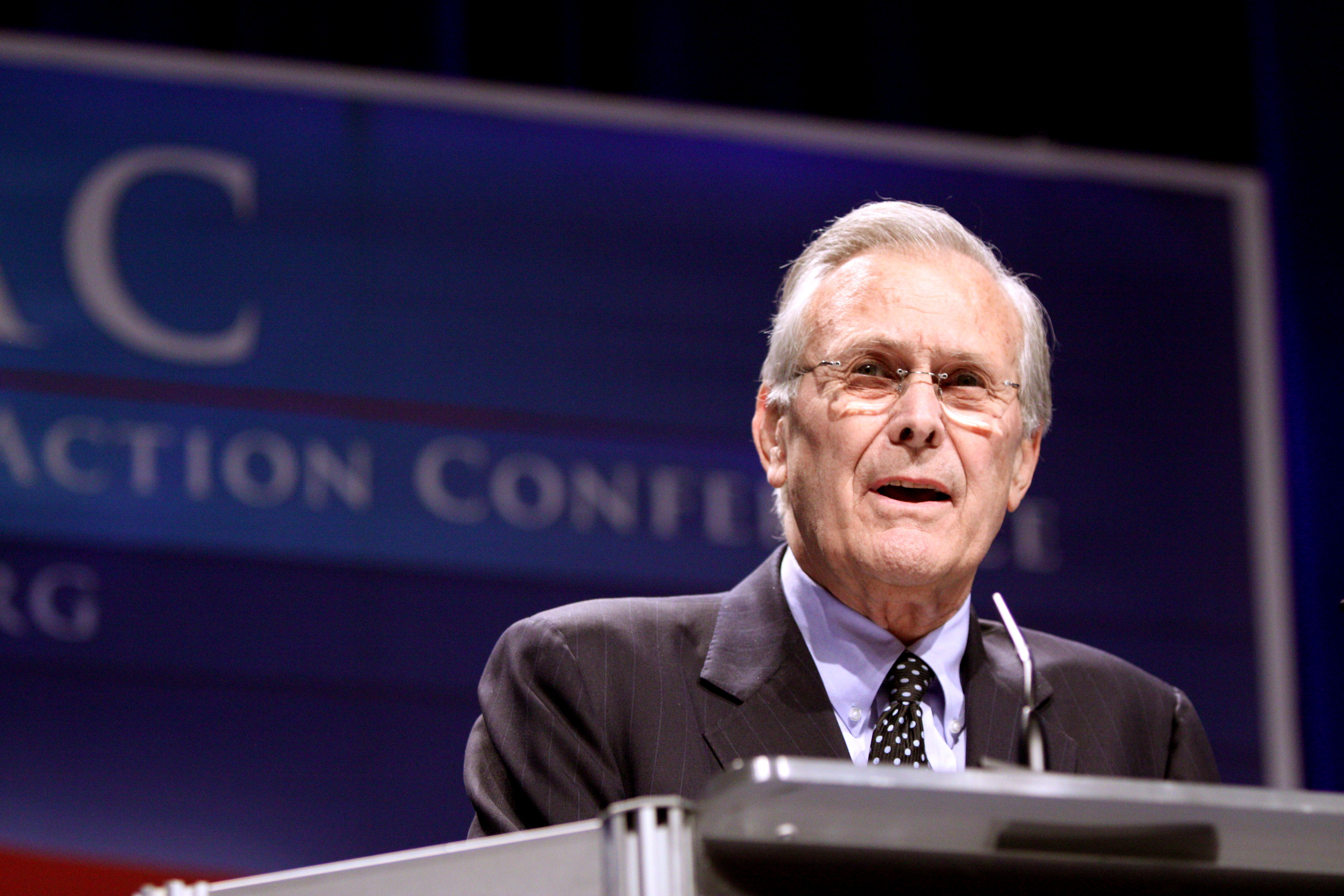

With the recent passing of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, it’s worth revisiting one of his most famous commentaries. In a news conference on Feb. 12, 2012, he said:

Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.

At the time, he was referring to intelligence reports stating that there was no evidence of a direct link between Baghdad and terrorist organizations seeking weapons of mass destruction, but Rumsfeld’s words have been cited widely as an epistemological characterization about knowledge in general.

But it is quite noteworthy that Rumsfeld omitted the obvious fourth category—unknown knowns—and contrary to his statement that it is “unknown unknowns” that tend to be the most difficult ones, I would suggest that unknown knowns pose the most difficult problems for people and nations to address.

What is an unknown known? Logic would suggest it is something that is “known” in some sense of that term, but that is, for all practical purposes, unknown at the time that it is needed. Things once known but now forgotten, things known but deliberately ignored, things that are known but that people wish were not true, and things once seen as scary, but no longer seen as such, all might qualify as unknown knowns.

Here are some examples of this phenomenon:

- The public “knows” that two-factor authentication is more secure than one-factor authentication, but the latter is still much more common than the former.

- Every major cybersecurity incident is bad enough to be a wake-up call for the nation. But mostly, nothing changes afterward as the immediate memories of the incident fade.

- What was a violent invasion of the Capitol to stop the certification of the Electoral College vote is now remembered by some as the actions of overly boisterous tourists.

- The United States saw the Soviets get bogged down in Afghanistan starting in 1979 for more than a decade, and we cheered. And then we did the same thing in 2001, only we stayed for twice as long.

- The U.S. judges the actions of other nations based on their potential to threaten U.S. interests but believes its own actions should be judged by its rhetoric about those actions regarding what they are intended to accomplish.

What is it about unknown knowns that makes them the most difficult problems to address? I believe it is the fact that, by definition, they are not a matter of factual or analytical or intellectual discovery. Science and the scientific method collectively do a pretty good job of producing reliable information (what might be called knowledge), at least as compared to individual human perception. Unknown knowns, by contrast, are driven not by knowledge but instead by human failings—and, as yet, neither science nor any other method of inquiry has developed particularly good methods for consistently ameliorating those failings.