The FTC Ups the Ante for Federal Privacy Legislation

The FTC has a complex and uncertain road ahead with its proposed rulemaking.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The Federal Trade Commission’s ambitious and diffuse advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) on “commercial surveillance and data security” comes against the backdrop of progress on privacy legislation in Congress. It was issued just three weeks after the House Committee on Energy & Commerce passed the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) and two weeks after the Senate counterpart approved two bills on strengthening privacy for children and teens. These bills would address many issues raised in the FTC’s ANPRM.

This context loomed large to FTC commissioners, who expressed differing views on the effect their proceeding could have on the passage of legislation. I once worried policymakers might think FTC action would forestall any need for congressional action, but now a comprehensive federal law to protect information privacy is a live possibility and the realities of the FTC proceeding bring home that legislation is a swifter, surer, and more comprehensive course.

The FTC has a complex and uncertain road ahead with its rulemaking. The rulemaking must follow the detailed and time-consuming steps to develop a supporting record required by Section 18 (b) of the Federal Trade Commission Act (codified at 15 U.S.C. § 57a). And even then, the outcome of the ANPRM is clouded by uncertainties about the scope of the rulemaking and its vulnerability to a federal judiciary increasingly antagonistic toward administrative authority. Privacy legislation may face some legal challenges, but these would not be as all-encompassing as challenges to FTC privacy regulations. By contrast, if the ADPAA is enacted, most of the law would go into effect 180 days from enactment, with regulations and guidance from the FTC in place and an individual right to sue for violations applicable within two years

I have long thought the FTC has been too timid about exercising its authority to adopt regulations to specify unfair as well as deceptive practices in information privacy. Given the challenges of doing so and the contingencies of legislation, I believe the FTC is right to begin the process. As FTC Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter explained her vote for the ANPRM: “The worst outcome … is not that we get started and then Congress passes a law; it is that we never get started and Congress never passes a law.” But if I had to put all my eggs in one basket, I’d stick with legislation.

This post explains why. Law firms and others have analyzed the ANPRM for its content, legal authority, and path forward more fully. I leave it to others like former FTC Consumer Protection Bureau chief Jessica Rich and colleagues at Kelley Drye & Warren; Kirk Nahra and Wilmer Hale; Omer Tene of Goodwin; and Jim Dempsey in Lawfare to explore these other aspects of the ANPRM. Below I focus more specifically on why FTC rulemaking is a poor substitute for comprehensive federal privacy legislation.

The Long, Tortuous Road of Rulemaking

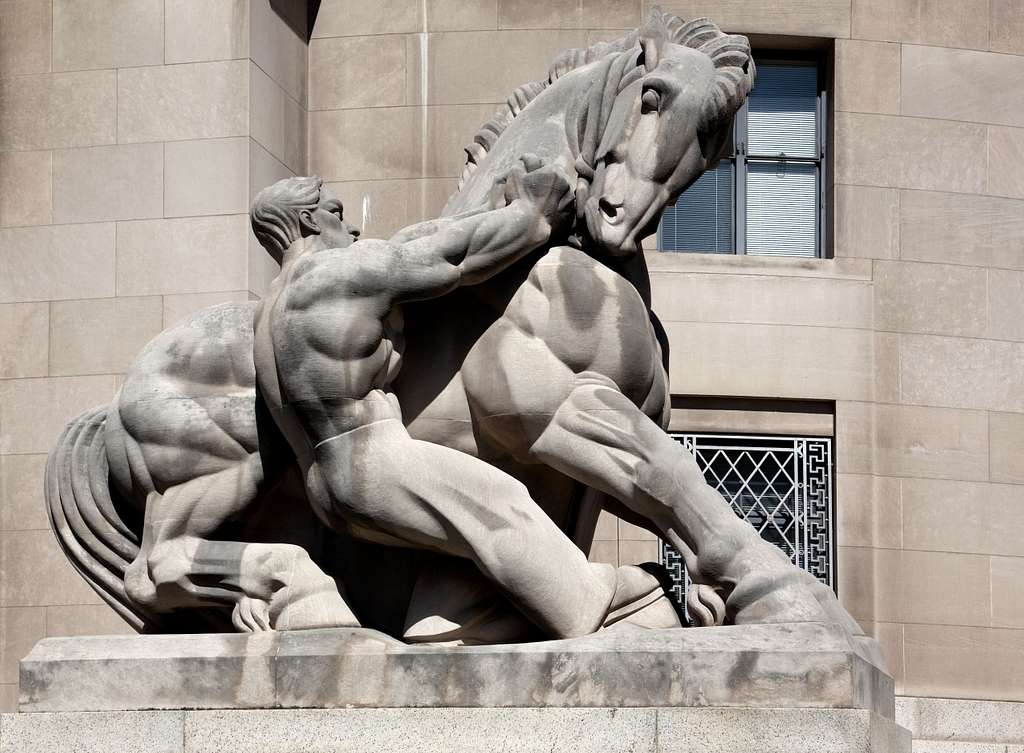

FTC Chair Lina Khan correctly described the ANPRM as “the beginning” in “an extensive series of procedural steps” required to adopt trade regulations. These requirements are outlined in Section 18(b) of the FTC Act, originally adopted in the Magnuson-Moss Act of 1976 with the initial step of advance notice of proposed rulemaking added by the Federal Trade Commission Improvements Act of 1980. There are several additional steps in the process, as illustrated in Figure 1, from the International Association of Privacy Professionals (open this link for a larger view).

Figure 1. Depiction of “FTC Privacy Rulemaking: The Steps to Get There,” produced by IAPP and originally appearing in the IAPP resource center.

Notably, unlike most rulemaking, “MagMoss” rulemaking must include “informal hearings.” These can become more formal on-the-record hearings with cross-examination of witnesses if the commission finds it needs to resolve disputed issues of material fact as well as additional notice rulemaking and public comment.

Until earlier this year, the last time the FTC initiated rulemaking through these MagMoss procedures was in 1980. The average timeline for adopting rules in earlier MagMoss rulemakings was 5.57 years (involving narrower practices and sectors than the FTC faces in the privacy rulemaking). At that rate, the FTC will be hard-pressed to arrive at any final privacy rules within the current presidential term. A change of party in the White House would result in a leadership that could change direction, and a change in Congress could bring the Congressional Review Act into play, enabling Congress to repeal newly-adopted rules.

And when and if the FTC reaches a final rule, it will face the near-certain prospect of judicial review. In June, the Supreme Court provided appellate judges with a neutron bomb against agency regulations with its decision in West Virginia v. EPA. The court articulated a “major questions” doctrine, constraining congressional delegation to administrative agencies in “extraordinary cases” without an unusually clear and precise grant of authority. The Magnuson-Moss Act is a more specific grant of authority than the Administrative Procedure Act rule at issue in the West Virginia case, but a court may read its numerous checks on the FTC authority through a similar lens. Most of the commentary on the ANPRM linked above sees a shadow of West Virginia over it.

All of these hurdles and uncertainties loom large in light of the extraordinary sweep of the FTC’s ANPRM. It invites comment on virtually every issue that touches on information privacy and does so with emphasis on potential harms of digital data use, especially when it comes to artificial intelligence and algorithmic decision-making of all kinds. While the ANPRM is more sparse about potential benefits, it does invite comments on these, consistent with Magnuson-Moss requirements for the use of FTC unfairness authority.

Ultimately, the commission will have to narrow its expansive and amorphous set of issues in the course of the iterative process ahead. In turn, whether any rules implicate the major questions doctrine will depend on their scope, the record developed throughout the process, and the extent to which the commission can link that record to widespread unfair and deceptive acts within its existing authority.

The ANPRM and Federal Legislation

When FTC Acting Chair Rebecca Slaughter initiated groundwork for rulemaking early in 2021, Congress appeared deadlocked on privacy legislation. In turn, the FTC looked like an alternative path to strengthen information privacy protections. That initially appeared to be the direction the Biden administration was taking with its July 2021 executive order on promoting competition. This order seemed to task privacy regulation to the FTC, calling out the impact of data aggregation on the economic power of large platforms without mentioning privacy but requesting the FTC to consider rulemaking on “unfair data collection and surveillance practices that may damage competition, consumer autonomy, and consumer privacy[.]”

With the ANPRM, the FTC is now moving ahead on this request. In the meantime, though, the landscape has shifted. Members of Congress have reached bipartisan agreement on several privacy bills, and the ADPPA has advanced. In the 2022 State of the Union address, President Biden said, “It’s time to strengthen privacy protections” and called on Congress to pass legislation to ban targeted advertising to children. The White House has been paying attention to the progress of negotiations on comprehensive privacy legislation.

FTC commissioners are conscious that the ADPPA addresses many of the issues raised in their proceeding. In their statements on the ANPRM, each commissioner reaffirmed support for privacy legislation in general or supported the ADPPA specifically, and expressed cognizance of the legislation’s potential effect on the proceeding or of the proceeding on passage of the legislation:

- Chair Lina Khan called recent steps to pass privacy legislation “highly encouraging” and said that if legislation is passed, the FTC “would be able to reassess the value-add of this effort and whether continuing it is a sound use of resources.”

- Commissioner Slaughter said she “welcomes” congressional progress on legislation but that the FTC should not wait to see if Congress acts. She later told a webinar that she hopes the bill passes.

- Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya gave a ringing endorsement of the ADPPA. He called it “the strongest bill that has ever been this close to passing,” said he hopes it does pass “soon,” and called out the bill’s chief sponsors for a “formidable and promising” accomplishment so far. He added that “[s]hould the ADPPA pass, I will not vote for any rule that overlaps with it” and that “[t]here are no grounds to point to in this process as reason to delay passage of that legislation.”

- Commissioner Noah Phillips, in a broadside against what he saw as breadth and lack of specific focus in the ANPRM, said it should be up to Congress and not the FTC to resolve many of the policy issues, that he is “heartened to see Congress considering just such a law today, and hope[s] this Commission process does nothing to upset that consideration.”

- Commissioner Christine Wilson, a strong supporter of privacy legislation who previously indicated she might entertain rulemaking on privacy, also praised the ADPPA: “I am heartened that Congress is now considering a bipartisan, bicameral bill that employs a sound, comprehensive, and nuanced approach to consumer privacy and data security. … [A]nd I hope to see this become law.” Like Bedoya, she name-checked the bill’s sponsors for their work, and she called out legislation on children in addition. Wilson attributed her vote against the ANPRM primarily to this support out of “grave” concern “that opponents of the bill will use the ANPRM as an excuse to derail the ADPPA.”

Some forces could derail the ADPPA, but I no longer see the prospect of FTC rulemaking as one of them. Leaders of the Commerce committees in both houses, as well as their members, have invested too much and gotten too close to leave the contours of privacy rules to the agency. And even the most sweeping FTC rules could not include major elements of legislation like preemption of state laws and a private right of action.

Reconciling FTC Rulemaking and Federal Legislation

Congress can “derail” the FTC rulemaking by enacting privacy legislation. This would obviate much of the rulemaking and give the agency a new set of tasks to provide required rules and guidance, carry out prescribed restructuring, and gear up for new enforcement responsibilities. These would certainly narrow its focus.

Congress can also help by being clearer about its reinforcement of agency authority and resources. It should be specific about the amount of funds authorized. The ADPPA has a provision (Section 407) that authorizes appropriation of “such sums as may be necessary to carry out” the law; by contrast, a privacy bill by Sens. Roger Wicker, R-Miss., and Marsha Blackburn, R-Tenn., specified an appropriation of $100 million. While such a provision does not guarantee appropriation of such an amount, it would make clear Congress’s intention to provide resources to go along with additional authority and would answer critics (including the California Privacy Protection Agency and its allies) who say the FTC does not have the established capacity to carry out ADPPA enforcement mandates.

Ultimately, if enacted in this Congress, legislation like the ADPPA could affect information privacy practices sooner and with greater stability than FTC regulations. Even more significantly, federal legislation could also preempt states’ comprehensive privacy laws and provide individuals a right to sue for violations, which even the broadest conceivable FTC regulations could not.

While my Brookings colleague Mark MacCarthy and I have different assessments of the relative prospects for legislation and rulemaking, we agree that the agency should not wait. If Congress does enact legislation, the rulemaking process allows plenty of time and checkpoints to change course, as FTC Chair Khan stipulates. And, as Kirk Nahra and colleagues put it, the rulemaking would offer “at least a backstop” if legislation fails. Though rulemaking is a poor substitute for legislation, it can improve the current losing game in which neither individuals nor the law can keep up with the pace and scope of data collection.

.jpeg?sfvrsn=f6228483_10)