Gen. Mark Milley’s Wrongful Jan. 6 Overclassification

Classifying information because it’s politically sensitive, as Gen. Milley did, undermines the public trust on which the entire system of national security secrecy rests.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

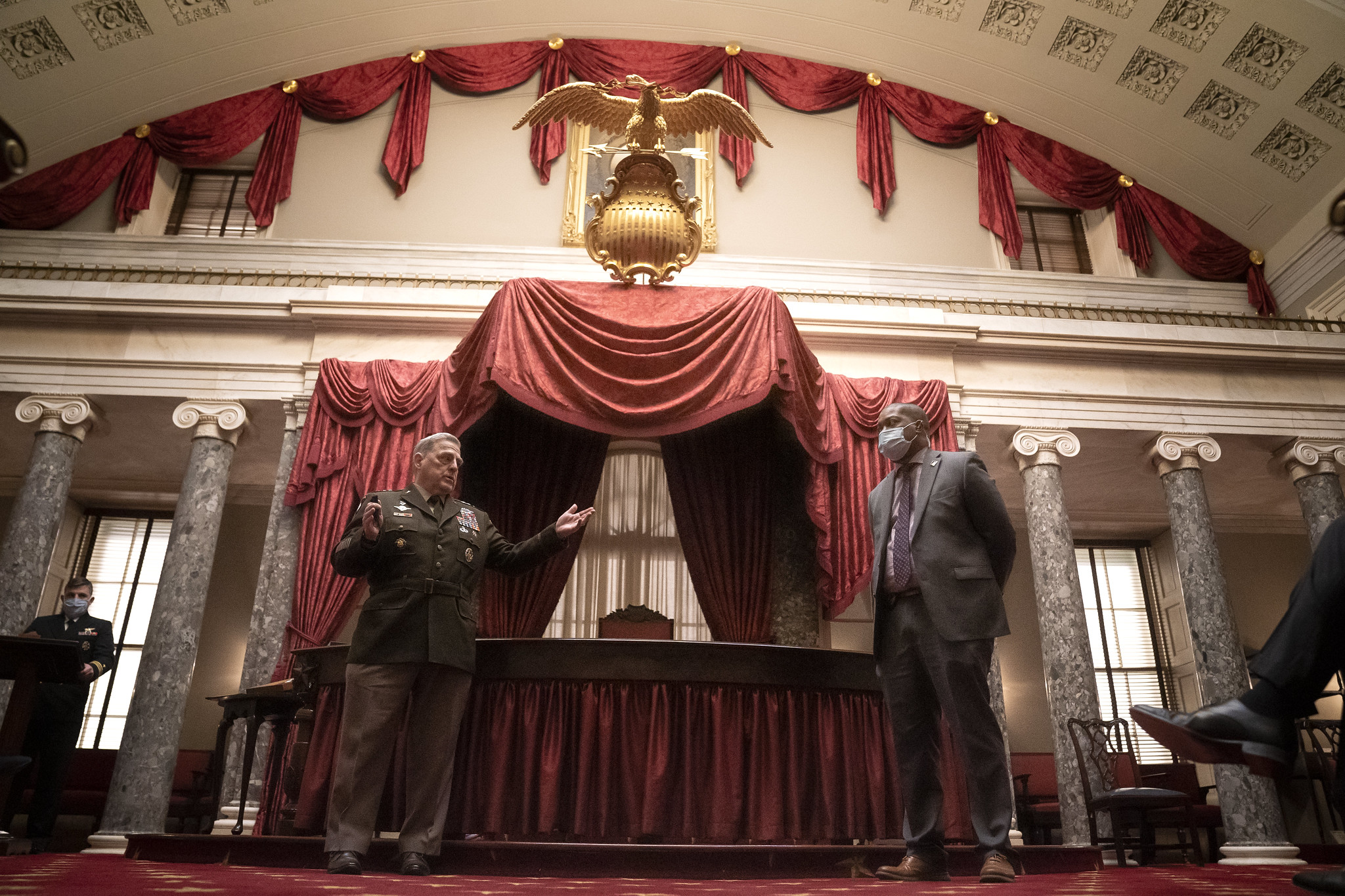

As the Jan. 6 committee released its final report and materials, it exposed norm-breaking in surprising places. Take the conduct of Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley, who testified that he had generated several timelines of the Pentagon’s conduct on Jan. 6, 2021, by assembling the relevant records and classifying them, even though, as he told the committee, “almost all of the substance is ... not classified”:

On this timeline, it’s actually classified, but, again, almost all of the substance is ... not classified. The document—I classified the document at the beginning of this process by telling my staff to gather up all the documents, freeze-frame everything, notes, everything and, you know, classify it. And we actually classified it at a pretty high level, and we put it on JWICS, the top secret stuff. It’s not that the substance is classified. It was[.] I wanted to make sure that this stuff was only going to go [to] people who appropriately needed to see it, like yourselves. We’ll take care of that. We can get this stuff properly processed and unclassified so that you can have it … for whatever you need to do.

Milley is right about the Joint Worldwide Intelligence Communication System, or JWICS. It’s a network for intelligence classified as top secret—the highest standard classification level, reserved by executive order for secrets whose compromise would “cause exceptionally grave damage to the national security.”

Milley is also right in recognizing that the records he moved to JWICS could not remotely meet the requirements for storage on that system. Despite that, Milley ordered them to be classified and moved onto the classified network to keep them from leaking—to make sure that the Pentagon and those investigating Jan. 6 would control the story.

By now, this story should sound eerily familiar. In 2019, President Trump held a phone call with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy of Ukraine. The call was immediately controversial inside the administration, and White House staff quickly restricted access to the call’s transcript by moving it to a server designed to protect highly classified intelligence activities. That move attracted press attention that was harsh, breathless, and extensive—even though such transcripts are usually classified, just not at a level that justifies use of the intelligence activity server. Former CIA Director Leon Panetta said that the use of a top-secret system was “clearly an indication that they were at least thinking of a cover-up if not, in fact, doing that. It’s a very serious matter because this is evidence of wrongdoing.” After considerable delay, the Trump White House released the transcript publicly, and one official acknowledged that it had been a mistake to move the transcript to a highly classified system.

That was the right answer. Overclassifying government records because of their political sensitivity is a direct violation of the executive order that governs classification. The order, signed by President Obama, says, “In no case shall information be classified in order to prevent or delay the release of information that does not require protection in the interest of national security.”

This is an important principle. Classifying information because it’s politically sensitive, however appealing it may be to government officials in the moment, undermines the public trust on which the entire system of national security secrecy rests.

But even setting aside the principle of the thing, overclassification is not a victimless crime. Take Milley’s decision to withhold records of the Pentagon’s response to Jan. 6. It raises serious questions that the chairman wasn’t asked in his testimony and that haven’t been answered since.

First, how long was this material locked up? Milley testified on Nov. 17, 2021, almost a year after Jan. 6, and he gave a clear impression that he was disclosing the Pentagon timelines and their underlying information for the first time.

Second, who was entitled to earlier access to the information he withheld? By the time of his testimony, many Jan. 6 defendants had already been charged. Many had already pleaded guilty. With exceptions I’ll get to, criminal defendants have a right to know about government records that would help them to defend themselves. It is not far-fetched to think that the overclassified records would have helped some of these defendants. To take one example, some defendants urged their compatriots to prepare for violence on that day. In an effort to take some of the sting out of their statements, many are claiming that they expected violence not from their allies but from their opponents on the left. This claim would be bolstered by evidence, referenced by Milley, including records showing that national security officials saw a serious risk of antifa and BLM attacks on Jan. 6, particularly the national security adviser’s belief that “the greatest threat is going to come from Antifa and Black Lives Matter assaulting the protesters.”

Third, did Milley’s overclassification of these records deprive the defendants of access to this information? We don’t know who else knew about the records. In general, the Justice Department would not be expected to search classified records for exculpatory information, so it may matter when the prosecutors learned about the records. Also relevant is how closely Justice worked with Defense. The obligation to search for exculpatory evidence may be limited to agencies that are part of the prosecution team. In arguing that the Pentagon should be seen as part of the Jan. 6 prosecutors’ team, though, defense counsel will no doubt point out just how eager Milley was to give the data to “people like” the Jan. 6 investigators—and how thoroughly the committee’s criminal referrals have mixed the fruits of its investigation with those of the Justice Department’s.

Fourth, what about Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests? There are no doubt boatloads of FOIA requests about Jan. 6 pending with the Defense Department. Were the overclassified records excluded from FOIA responses? FOIA doesn’t generally apply to properly classified records. But these are not properly classified. As Milley makes clear, “almost all” of the substance of the material isn’t classified at all. Did his overclassification of this information delay disclosure of important insights about the Pentagon’s actions on Jan. 6?

We don’t have answers to those questions, but we deserve them.

I frequently defend broad national security authorities for government. That’s because I’ve seen some of the threats the government faces. But if it wants to keep those authorities in a time of deepening public suspicion, the government must show that it has internal checks and real accountability to prevent abuse.