Getting the Drop in Cyberspace

Gen. Mark Milley, recently confirmed by the Senate as the next chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, will soon ascend to that position after the current chairman, Gen. Joseph Dunford, retires this fall. In testimony during his confirmation hearing, Milley argued that in cyberspace, peace can be achieved through strength: “We have to have those offensive capabilities ...

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Gen. Mark Milley, recently confirmed by the Senate as the next chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, will soon ascend to that position after the current chairman, Gen. Joseph Dunford, retires this fall. In testimony during his confirmation hearing, Milley argued that in cyberspace, peace can be achieved through strength: “We have to have those offensive capabilities ... and in the theory of deterrence, if [adversaries] know that we have an incredible offensive capability, then that should deter them from conducting attacks on us in cyber.”

I call this the Cartwright Conjecture, after one of its early proponents, Gen. James Cartwright, who pushed it in 2011. Proponents of offense-assisted defense do not deny the role of defense. But they do elevate the priority of offense, believing a new approach is overdue. Proponents believe that more action will not only yield defensive benefits but may just be the most impactful approach ever taken. This is a risky proposition—and, to make matters worse, there is little evidence that it is actually true.

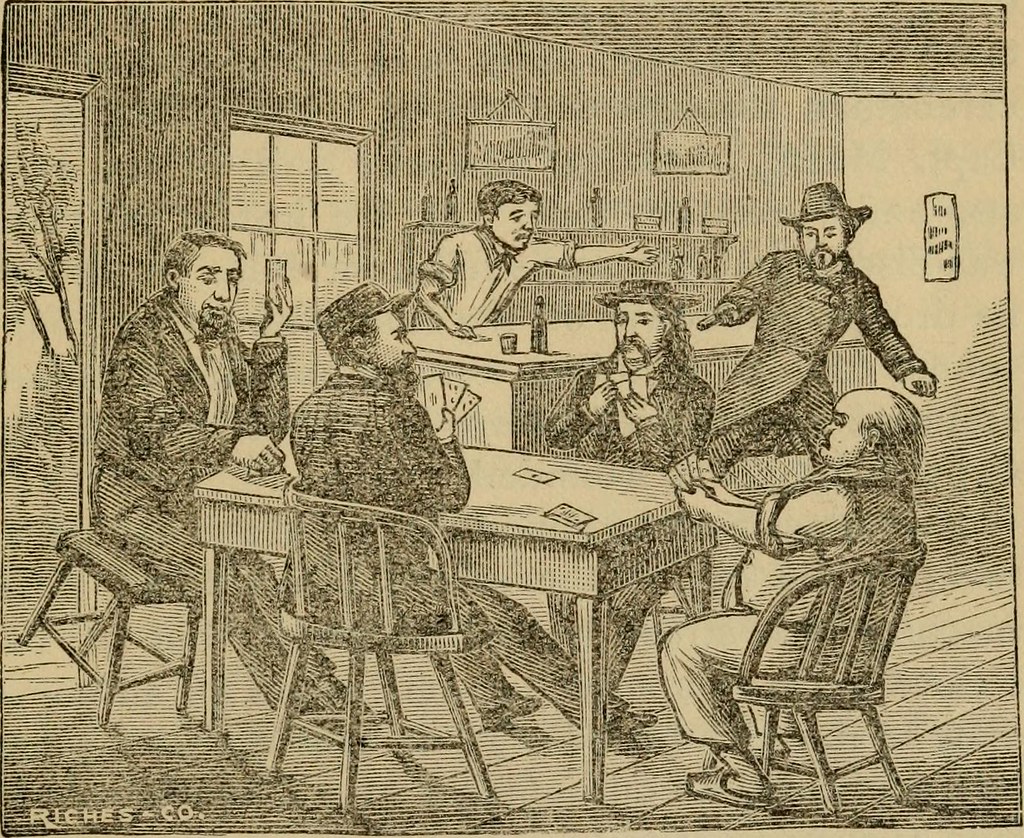

To understand why it is risky, let’s take a detour to Deadwood, South Dakota, in 1876. Wild Bill Hickock, the legendary gunfighter of the Wild West, was famously shot in the head from behind while playing poker in Deadwood. His killer, Crooked Nose Jack McCall, shouted “take that” before he pulled the trigger. McCall’s actions were cowardly but understandable, given that he was facing a murderer who boasted of the hundreds of men he’d killed and who never missed a shot. There are key lessons for the new U.S. cyber strategy built on “defending forward” and deterrence. Cyber defense is hard. There are at least a dozen reasons why the attackers have held most of the advantages for decades. For the typical person online, and even for Fortune 500 companies, there’s nothing for it but to try to put in the effort and money to be as secure as possible. It isn’t cheap; JPMorgan Chase reportedly spends at least $600 million annually for cybersecurity.

But governments, unlike private entities, have other options. Given that the United States has the best cyber offense in the world, it has long been tempted to use that power to improve its defense. National Security Adviser John Bolton is among those pushing for more cyber offense, loosening the rules so that, in his words, “our hands are not tied” anymore. The United States, Bolton declared in September 2018, “will respond offensively as well as defensively” and will use offensive cyber operations to impose costs on adversaries and create “structures of deterrence.” In line with this approach, the military now has reduced operational constraints to pursue its strategy of “defending forward to intercept and halt cyber threats,” including responding with (counter)offensive measures. This could include, for example, disrupting an Iranian botnet attacking U.S. financial targets or causing friction by undermining Russian espionage infrastructure so that they spend more time defending themselves, rather than spying on us.

Yet U.S. cyber defenses are not just bad but appalling. This mismatch of offense and defense is just one more reason that the strategy that “the best defense is a good offense,” as Sen. Richard Blumenthal put it to Milley, is especially risky. The pressures to strike early could become an imperative when facing cyber-strong but technology-dependent countries like the United States. After all, U.S. leadership has actively emphasized its fear that a cyber Pearl Harbor attack would “paralyze and shock the nation,” to quote former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta.

Sixty years ago, during the Cold War, the preferred plan of Strategic Air Command (SAC) was to maximize striking potential by basing nuclear-armed bombers as close as possible to the Soviet Union. Albert Wohlstetter wrote in a RAND Corp. report that this invited a surprise attack: The bombers and tankers parked on those bases would be both existentially threatening to the Soviet Union and themselves vulnerable to a Soviet nuclear attack. They were also positioned so close to the Soviet Union that adequate warning of such an attack would be unlikely. The combination of a terrifying offense and weak defense would create perverse incentives for the Soviet leadership to launch a disarming strike as early as possible in any crisis. The only winning move would have been to strike first, before the SAC force itself could launch to deliver its own killing blow.

This is what ties the death of Wild Bill Hickock to international relations theory. In cyberspace as in Deadwood, some adversaries will choose the surprise attack rather than waiting to face off with the deadliest gunfighter around. Indeed, the more the gunfighter improves on and boasts about his deadliness, the more he brandishes his pistols, the more incentive there is to get the drop on him, especially if a fight seems inevitable anyhow.

Moreover, there is little evidence that having exquisite offensive cyber forces deters attacks. In fact, the most direct evidence available only demonstrates that the U.S. is deterred by others’ capabilities, not the other way around. This is, of course, not the kind of deterrence the U.S. wants. During debates over how to respond to Russian election interference in 2016, the White House reportedly took several response options off the table because of Russian capabilities and fear of escalation. It is not clear, though, that adversaries feel the same pressure.

After Stuxnet and the Snowden revelations, what adversaries can possibly doubt the power of U.S. cyber capabilities? And yet, years later, the White House still complains that “adversaries have increased the frequency and sophistication of their malicious cyber activities.”

Indeed, there is evidence that the power of U.S. offensive capabilities has not deterred threats but, instead, has done the opposite. Iran became a far more serious cyber threat after Stuxnet. For the U.S. to have the “incredible offensive capability” described by Milley may only invite adversaries to drastically improve the size of their own cyber commands and their cyber arsenals.

Gen. Paul Nakasone, head of U.S. Cyber Command, might disagree with Milley: Nakasone recently wrote that “[u]nlike the nuclear realm, where our strategic advantage or power comes from possessing a capability or weapons system, in cyberspace it’s the use of cyber capabilities that is strategically consequential” (emphasis added). This represents a fundamentally different view than Milley’s: Peace and stability do not come through strength itself, but through the use of that strength. The gun can’t stay in the holster; it must be drawn and used. Success therefore comes from the cumulative effects of the struggle of U.S. cyber forces against those of Iran, Russia, North Korea and China, and the active emplacement of malicious implants in targets those states value. This isn’t deterrence but warfighting, albeit without the war (or, at least, without the war just yet).To reduce the risk, the U.S. needs a new strategic goal. The current U.S. strategies insist on achieving both stability and superiority. But the U.S. cannot reserve the unilateral right to a cyber first strike. Cyber strategies are more likely to be successful if they focus on stability, rather than deterrence, as the primary goal.

A focus on stability can directly reduce miscalculation and mistake and crisis stability, including the pressures to attack first. Stability can be met through a wide range of means, not just cyber and other military capabilities but also transparency and confidence-building measures. At the same time, when deterrence is the primary goal, as it is now in U.S. strategy, there is no obvious upper limit to the number of cyber forces required.

From Wild Bill to Wohlstetter, the U.S. should learn the lesson of the risks of a fearsome offense paired with a weak defense. Using offensive forces to improve defenses may be satisfying and might even work in the short term. But if adversaries feel a war with the United States is coming, a more fearsome cyber offense makes it more likely they will go Deadwood on the U.S. before Cyber Command can bring its big guns to bear.

.jpg?sfvrsn=b3d4eb92_7)