Giuliani Cannot Rely on Attorney-Client Privilege to Avoid Congressional Testimony

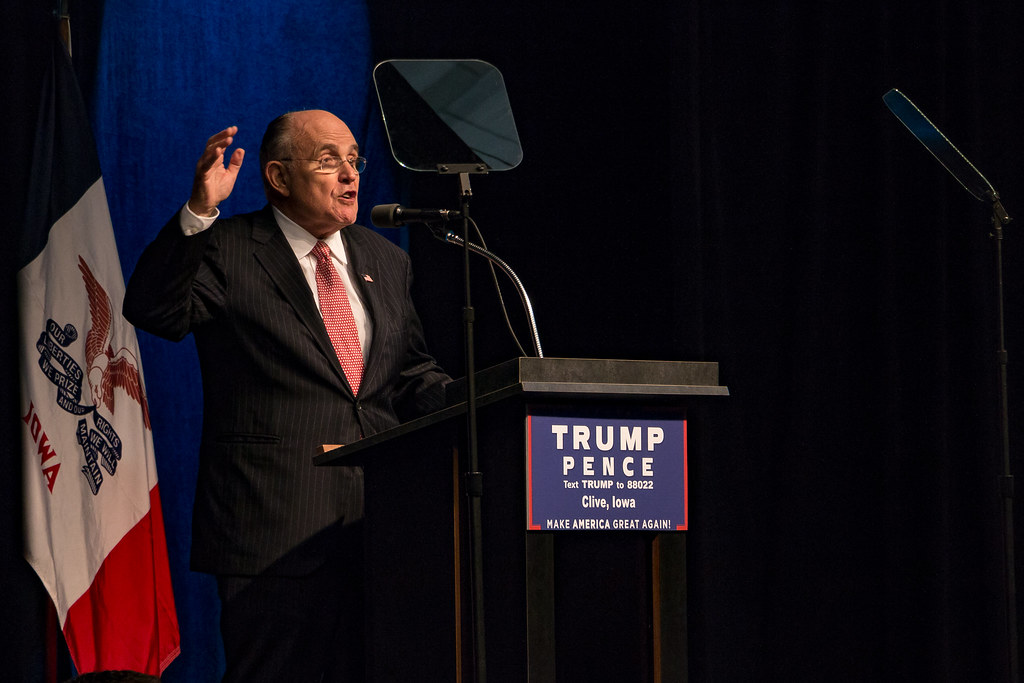

As the House of Representatives launches its impeachment inquiry with a focus on President Trump’s efforts to pressure Ukraine, the question has been raised whether the president’s personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, will testify before Congress. According to CNN, Giuliani has said that he would need to consult with Trump before testifying before Congress because of the attorney-client privilege.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

As the House of Representatives launches its impeachment inquiry with a focus on President Trump’s efforts to pressure Ukraine, the question has been raised whether the president’s personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, will testify before Congress. According to CNN, Giuliani has said that he would need to consult with Trump before testifying before Congress because of the attorney-client privilege. This reflects a fundamental misapprehension of how the attorney-client privilege might apply in these circumstances—and, indeed, whether it could provide a bulwark against compelled congressional testimony at all.

At the outset, it is unclear that much of the information of interest to Congress regarding Giuliani’s conduct would even potentially be subject to the attorney-client privilege. The privilege exists to protect the confidential communication between a client and an attorney made for the purpose of obtaining legal advice. It does not protect, for instance, communications your attorney may have had with, say, foreign government officials—or, for that matter, with U.S. government officials.

And, of course, the privilege wouldn’t reach communications where Giuliani was not acting in his capacity as a lawyer providing legal advice. Yet Giuliani himself just told The Atlantic regarding his work in Ukraine, “I’m not acting as a lawyer. I’m acting as someone who has devoted most of his life to straightening out government.” And the conduct at issue—pushing arguments about potential corruption to foreign officials—does not appear to involve providing confidential legal advice. It is not even clear that Giuliani’s conduct constitutes legal work performed in his capacity as Trump’s attorney, even if it were charitably viewed as something other than political campaign work.

Nor does the course of dealing, so far as it is presently known, suggest that Trump was conveying confidences to Giuliani for the purpose of receiving legal advice from him, rather than directing him to undertake other (nonlegal) activities on the president’s behalf. Directives of this sort, of course, would not be privileged. Indeed, it is not clear what legal advice the president would have needed regarding corruption in Ukraine, at least prior to recent developments. So reasonable minds might question whether any of the communications between the president and Giuliani are protected by the privilege, much less information regarding Giuliani’s other conduct and interactions with third parties.

But even positing for the sake of argument that there may be some communications on the Ukraine issues that might potentially be subject to the privilege, those residual “privileged” communications would have little protection against compelled congressional testimony.

First, it is Congress’s long-standing position that the attorney-client privilege does not afford protection against compelled congressional testimony. Although Congress may consider claims of attorney-client privilege at its discretion, it does not recognize the common law privilege as a bar to compelled disclosure. Rather, it has consistently taken the position that it can insist that privileged communications be disclosed. Consistent with this position, a committee that calls Giuliani for testimony can simply direct him to answer if he were to attempt to assert attorney-client privilege, and can hold him in contempt if he does not comply.

Second, attorney-client privilege can be waived. Under the third-party waiver doctrine, disclosure of privileged communications to a third party typically effects a waiver of the privilege. And in order to prevent the use of the privilege as both a sword and a shield at the same time, the subject-matter waiver doctrine holds that any waiver of the attorney-client privilege generally extends to the entire subject matter to which the disclosed communication related, not just the specific communication disclosed. To the extent that the efforts with Ukraine at issue here appear to involve a large number of people, and in light of the fact that both the president and Giuliani have been publicly discussing those efforts, there may be good arguments that there has been a waiver as to some, if not all, of the communications.

Third, there is a crime-fraud exception to the attorney-client privilege. Communications seeking advice related to the current or future commission of a crime, rather than the consequences of past actions, are not protected by the privilege. In light of the substantial questions that have been raised as to whether these events contain a violation of campaign finance law, or indeed another crime, it is possible that this too might preclude an assertion of the privilege.

If the attorney-client privilege is not available to Giuliani, what about executive privilege? The administration has recently claimed that executive privilege can shield the president’s communications even with some individuals outside the executive branch. But even setting aside questions about whether such an extension of the privilege is supportable, there is a separate reason it cannot be available here: Giuliani represents Trump in the president’s personal capacity, not his official capacity.

Executive privilege, of course, exists to protect the president’s ability to perform his constitutionally assigned—that is, official—functions. Indeed, two circuit courts considering similar privilege and waiver questions during the Whitewater investigations found the divergence of interests between personal capacity and official capacity representations to be significant. It is not clear how it would be possible here to reconcile Giuliani’s obligations as a lawyer for the president in his personal capacity, on the one hand, with the limitation of executive privilege to circumstances where it is necessary to protect the president’s ability to effectively perform his constitutional functions, on the other. As these two cases make clear, representing the president in his personal capacity involves a different set of interests and concerns than the official, governmental decision-making processes executive privilege is designed to protect.

Thus, to the extent Giuliani has been relying on privilege as a way to avoid testifying before Congress, he may need to think again.