Grab 'em by the Constitution: Trump and the Justice Department

I hate to say "I told you so," but gosh, I told you so.

A few months ago, during Trump's ascendancy in the GOP primaries, I wrote a piece about his likely impact on and abuse of the powers of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

I hate to say "I told you so," but gosh, I told you so.

A few months ago, during Trump's ascendancy in the GOP primaries, I wrote a piece about his likely impact on and abuse of the powers of the U.S. Department of Justice.

In response to this piece, I received an email that had no parallel in the prior history of this site: an actual request for an ethics opinion from a career DOJ lawyer about the propriety of continuing to serve in the Justice Department under a President Trump. I responded to it here.

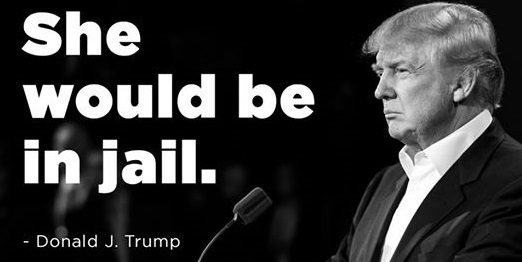

The premise of this whole discussion was that we should take Trump seriously when he promises to use the powers of the U.S. federal government, particularly its routine criminal enforcement powers, to do things that are grossly improper. Last night at the second presidential debate, as if to emphasize this point, Trump specifically promised to use the law enforcement authorities of his office to go after his opponent, Hillary Clinton:

In my opinion, the people that have been long-term workers at the FBI are furious. There has never been anything like this, where e-mails—and you get a subpoena, you get a subpoena, and after getting the subpoena, you delete 33,000 e-mails, and then you acid wash them or bleach them, as you would say, very expensive process.

So we're going to get a special prosecutor, and we're going to look into it, because you know what? People have been—their lives have been destroyed for doing one-fifth of what you've done. And it's a disgrace. And honestly, you ought to be ashamed of yourself.

RADDATZ: Secretary Clinton, I want to follow up on that.

(CROSSTALK)

RADDATZ: I'm going to let you talk about e-mails.

CLINTON: ... because everything he just said is absolutely false, but I'm not surprised.

TRUMP: Oh, really?

CLINTON: In the first debate...

(LAUGHTER)

RADDATZ: And really, the audience needs to calm down here.

CLINTON: ... I told people that it would be impossible to be fact-checking Donald all the time. I'd never get to talk about anything I want to do and how we're going to really make lives better for people.

So, once again, go to HillaryClinton.com. We have literally Trump—you can fact check him in real time. Last time at the first debate, we had millions of people fact checking, so I expect we'll have millions more fact checking, because, you know, it is—it's just awfully good that someone with the temperament of Donald Trump is not in charge of the law in our country.

TRUMP:

This was not a slip of the tongue or a slip of Trump's id. I know this because it is not the first time Trump has said things like this. Back in June, Trump appeared on CBS's Face the Nation, where he had the following exchange with host John Dickerson in which he both pronounced Clinton guilty of crimes and declared that he would have her investigated and prosecuted for them:

DICKERSON: You said Hillary Clinton should go to jail. If the FBI, which is investigating, if there's no indictment, will your attorney general go after her?

TRUMP: OK. So, I have spoken to, and I have watched and I have read many, many lawyers on the subject, so-called neutral lawyers, OK, not even on one side or the other, neutral lawyers. Everyone of them, without a doubt, said that what she did is far worse than what other people did, like General Petraeus, who essentially got a two-year jail term.

General Petraeus and others have been treated—their lives have been in a sense destroyed. She keeps campaigning. What she did is a criminal situation. She wasn't supposed to do that with the server and the emails all of the other.

Now, I rely on the lawyers. These are good lawyers. These are professional lawyers. These are lawyers that know what they're talking about and know—are very well-versed on what they did. They say she's guilty as hell.

DICKERSON: But it sounds like you were making promise for your attorney general that, if you were elected, this is one of the things—this is a commitment you were making.

TRUMP: That's true, yes.

DICKERSON: It's a commitment to have your attorney general...

TRUMP: Certainly have my—very fair, but I would have my attorney general look at it.

DICKERSON: Even if the investigation...

(CROSSTALK)

TRUMP: You know you have a five and maybe even a six-year statute of limitation.

DICKERSON: But even if the current investigations don't find anything, you would have your attorney general go back at it?

TRUMP: Yes, I would, because everyone knows that she's guilty. Now, I would say this: She's guilty. But I would let my attorney general make that determination. Maybe they would disagree. And I would let that person make the determination.

It is worth emphasizing that a President Trump would certainly have the raw constitutional authority to do what he is promising here.

The attorney general serves at the pleasure of the president and thus can be directed to do as the president pleases. He can be fired if he does not do so and replaced with someone who will. The president also has the authority to have the attorney general name a special prosecutor. Assuming, perhaps charitably, that Trump's promise to jail Clinton is a promise to do so only after she is indicted and convicted of crimes, he has the power to do that too, provided that the special prosecutor he has named or the attorney general he directs can actually make and prove a case against her. I have serious doubts that there is any such case to make, given that FBI Director James Comey has said flatly that "no reasonable prosecutor" would bring a criminal against Clinton. But let's be clear that Trump here is not promising to do anything the president lacks the constitutional authority to do.

Yet Trump's comments induced horror among many commentators—and rightly so. The reason? His promise tramples on a number of cherished norms in the relationship between the Justice Department and the White House and in the conduct of the Justice Department itself. These norms restrict presidential and departmental behavior far more than the bare bones strictures of the Constitution. They are part of our constitutional fabric and rooted in important constitutional values. But our mode of enforcing them is not legal. It is political. It is a matter of our deepest expectations of the presidency and the Justice Department.

One of these norms is that the Justice Department doesn't use the criminal enforcement powers of the federal government to go after the administration's political opponents. This is the idea of impartial justice. But don't kid yourself. The Constitution does not require impartial justice. The president has enormous discretion—which, put more crudely, means that we expect him to discriminate. One possible basis for this discrimination is how much he likes or dislikes you. Most people have committed crimes if you look hard enough to find them. What prevents administrations from focusing on the crimes of their opponents, rather than the most serious crimes committed by whomever, is nothing more than the institutional expectations we have of the executive branch—and it has of itself. These expectations sound less in law than they do in decency and civic virtue. What Trump is promising here is precisely war on that decency and civic virtue.

Now, to his credit, he's being quite open about it: He's saying that a major law enforcement priority of his administration would be the prosecution of his opponent for acts the Justice Department and FBI have already investigated and found either non-criminal or not warranting action. "It is here," said Justice Robert Jackson while still attorney general, "that law enforcement becomes personal, and the real crime becomes that of being unpopular with the predominant or governing group, being attached to the wrong political views, or being personally obnoxious to or in the way of the prosecutor himself."

Another norm Trump's promises assault is the notion that while the Justice Department is part of the administration and the President is thus entitled to set policy priorities for it, the White House does not involve itself in or direct specific law enforcement operations or decisions. People don't believe this, but it really is true; it's a norm that guides the Justice Department across administrations of both parties. The President rightly decides whether drug enforcement or terrorism or child pornography or guns or financial crimes are enforcement priorities on which he thinks it important to focus. But when it comes to investigating or indicting someone, the White House generally makes a point of not getting involved—even in the highest-stakes cases. How did President Obama handle the decision of whether or not Khalid Sheikh Mohammad should be tried in federal court or in a military commission, to cite one example of interest to readers of Lawfare? At least initially, as Daniel Klaidman reports in his book Kill or Capture, he didn't:

On the Fourth of July, Obama and Holder stood together on the White House roof terrace watching fireworks explode over the National Mall, the Lincoln and Washington Monuments aglow at either end. Holder was flush with pride. He was the country's first black attorney general, standing with its first African American president, both guardians of the Constitution, presiding over a White House celebration of Independence Day. But he wasn't going to waste a rare moment alone with the president. He had come with an agenda, and told the president that he was thinking about prosecuting KSM in federal court. Obama had simply acknowledged that he would defer to Holder on the matter: "It's your call, you're the attorney general."

Obama only got involved and reversed Holder, when it became clear that the political system would not sit still for a 9/11 trial in New York.

When the White House does get involved in day-to-day Justice Department business, bad things happen. Remember the U.S. attorneys scandal from the late Bush administration? It was about exactly this separation. But that was small potatoes—the mere dismissal of U.S. attorneys who weren't sufficiently on board administration enforcement priorities. It mostly didn't involve interventions in specific enforcement matters, much less anything so grotesque as an instruction to investigate or prosecute political opponents. That was amateur hour compared to what Trump is proposing.

Still another norm, one sometimes honored in the breach, is that senior law enforcement officials are not supposed to publicly presume someone's guilt. It is always wrong for the President to pronounce someone guilty who has not yet been charged. It is even wrong for the President, or the attorney general for that matter, to declare that someone is guilty who has been charged but not yet convicted. Look at any press release announcing a Justice Department indictment and you'll find language like this: "An indictment is merely a formal charge that a defendant has committed a violation of criminal laws and every defendant is presumed innocent until, and unless, proven guilty."

The press is similarly quite disciplined on this point as well, using the word "allegedly" as a matter of principle before factual claims where a defendant has not yet been convicted. Journalists do this not because they believe, in many cases, that there is any factual doubt about the defendant's conduct but because it's a core value of our system that we do not impute guilt until either a defendant has acknowledged it or that guilt has been proven in court beyond a reasonable doubt to the satisfaction of a jury.

When Trump declares that Clinton would "be in jail" if he were president and that "everyone knows she's guilty," by contrast, he's doing violence to the presumption of innocence every bit as much as he does when he declares guilty the now-cleared men convicted in the Central Park jogger case. In both instances, Trump's conduct is made worse by the fact that these matters were exhaustively investigated, and prosecutors concluded that the evidence simply does not support the position Trump nonetheless holds.

Trump's promise both in the debate and in the CBS interview is a threefer that violates all of these norms at the same time: It's a promise of an overtly political prosecution, directed from the White House, and with a public presumption of guilt declared in advance by the president.

This is Putin-Erdogan territory, folks. It's toxic stuff.

And it's a reminder of how much of our constitutional system does not reside in the Constitution itself but in the hearts of the people who take an oath to it. It's a reminder as well that without the norms of civic decency in which we encase the Constitution, the document itself will not save us.

If we vote for a tyrant, we will get a form of tyranny.

ADDENDUM: Former DOJ Civil Division head and Acting Attorney General Peter Keisler emailed me with the following important point I should have thought of myself in writing this piece:

In addition to the three important norms you explain such a statement violates, there’s a fourth: this wasn’t an action by a sitting President, but a campaign promise to take such action by a candidate. So on top of the fact that this would be a deeply improper action for any President to take, we also have the specter of someone running for office asking people to vote for him based on a promise to investigate and jail a particular person—having a national referendum over (in part) whether someone should be prosecuted. One could debate whether it’s better or worse to have prosecutorial decisions corrupted by the White House or by being subject to a popular vote, but worst of all is to have both.