Great Power Competition and Internal Politics in Asia, Then and Now

International rivalries can draw powerful states into local political disputes—sometimes with disastrous consequences—but the United States and China can avoid the mistakes of the Cold War.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

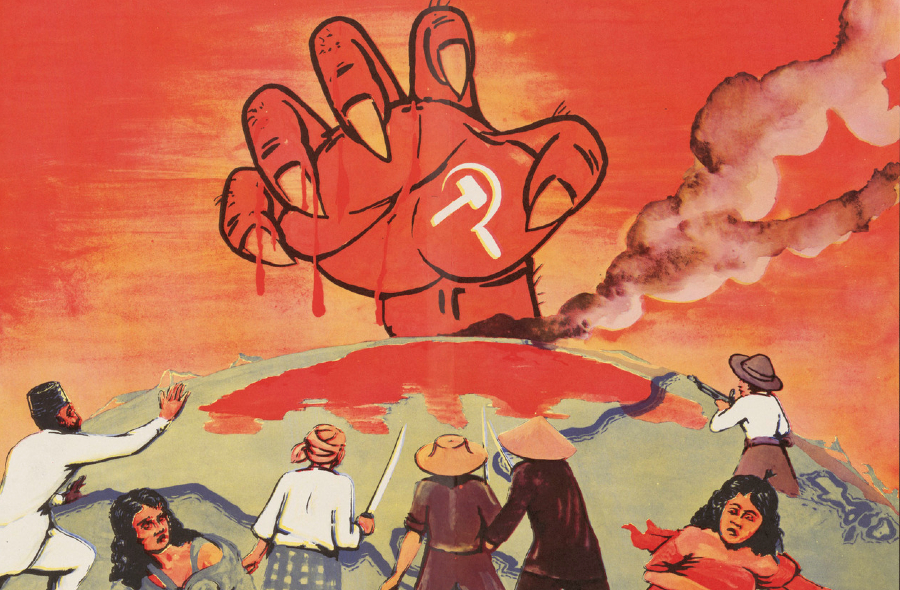

Editor’s Note: As the U.S.-China rivalry increases, worries abound that a new Cold War will develop. For Asia, this concern is particularly ominous, as the Cold War there contributed to numerous bloody internal conflicts. Paul Staniland of the University of Chicago examines this period to draw lessons for how the region may respond to U.S.-China tension and how policymakers should consider the interplay between internal crises and foreign policy goals.

Daniel Byman

***

Competition between the United States and China in Asia has generated ongoing discussion about whether Asia’s present will resemble its Cold War past. In one key area, the contemporary period is—at least so far—much less dangerous. From the 1940s through the 1980s, Asia’s Cold War intertwined major power rivalry with intense local struggles for power and influence. Domestic political competition was frequently embedded within and connected to external geopolitics, producing complex, and often violent, outcomes.

Classic questions of strategy and statecraft could not be cleanly separated from internal political struggles for power, legitimacy, and control. The “authoritarian Leviathans” of Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia deployed anti-communism at home and abroad. Marxist-Leninist regimes with strong ties to the Soviet Union, China, or both emerged and consolidated in Laos and Vietnam. Militaries in Thailand and Pakistan mobilized Cold War fears and U.S. support to protect their political power. South Vietnam, Laos, Afghanistan, and Cambodia experienced extraordinary levels of instability and civil war, with internal armed actors closely linked to, though not fully controlled by, external players. The Sino-Soviet split and India-China competition also influenced the internal politics of states in the region.

This fusing of the global and local was not universal—India was comparatively insulated from these Cold War currents, for instance—but it helped to spur extraordinary levels of violence and political instability from 1946 until the mid-1970s in Southeast Asia, and then the fragmentation of Afghanistan and its spillover in the 1980s.

From the mid-1970s, as civil wars reduced in intensity, governments stabilized, and the Cold War ended, much of Asia became more stable, more prosperous, and a closer approximation of the “billiard ball” model of coherent sovereign states interacting with one another (if crosscut by growing commercial exchange). Regimes consolidated themselves through varying blends of revolutionary or counterrevolutionary state-building, international backing, and ethno-nationalist and ideological projects. At the same time, development, democratization, or both further stabilized many polities compared with the early decades of the Cold War.

The post-Cold War environment was therefore radically different from what had come before. While today’s U.S.-China competition over technology and the balance of military power is enormously important, the region has lacked the distinctively destabilizing dynamics of 1946-1989. That period will not mechanistically repeat itself; large-scale internal warfare and violent instability in particular seem far less likely now than during the Cold War.

Nevertheless, intensifying U.S.-China rivalry has the potential to become a live issue in domestic politics across Asia. Analysts, scholars, and policymakers need to be attentive to the unpredictability and complexity that result from the interactions of local politics and geopolitical rivalry.

We have already seen early glimmers of this dynamic—with very different manifestations. In the Solomon Islands, the government’s 2019 change in diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the People’s Republic of China intersected with complex internal political divisions, contributing to violence in late 2021. In Nepal earlier this year, political parties competitively mobilized around a Millennium Challenge Corporation agreement. China, India, and the United States have all devoted substantial effort to engaging with political forces in the country. In Indonesia in 2019 and Malaysia in 2018, the issue of Chinese capital and labor were deployed by politicians in general elections, tapping into deep ethnic and religious cleavages within these countries. Sri Lanka’s recurrent crises have created incentives and opportunities for China, India, and the United States to seek influence in the strategic island. None of this is purely reducible to foreign policy, but all of these politics have become, in various ways, linked to external rivalries.

Internal conflicts in Afghanistan and Myanmar may also become arenas of competition among outside powers. Even after the Taliban’s seizure of power, Afghanistan continues to be a site of political violence that is of deep interest to external states. Myanmar’s bloody civil war shows no sign of ending any time soon. China has been supporting the military regime and restraining a set of ethnic armed groups from turning against the government, increasing the potential for an anti-China cleavage to grow in prominence within Myanmar. Even before the 2021 coup, there had been nationalist backlash against Chinese projects. In Pakistan, Chinese support for infrastructure projects led to Chinese nationals being targeted by Baluch insurgents.

Major powers may be increasingly motivated to influence the balance of domestic power in countries around the region to shape these states’ foreign policy alignments. There will certainly be many opportunities for them to do so. In the face of this emerging landscape, the experience of the Cold War provides some useful lessons for today.

Notably, geopolitical competition and local politics can overlap in a variety of ways. Geopolitics may be relatively easily connected to salient internal political divisions. For instance, Taomo Zhou shows how relations between Indonesia and China in the 1950s and 1960s “inevitably intersected with communal politics and ethnic tensions” over the position of ethnic Chinese in Indonesian politics and society. During the Cold War, the domestic power of the Thai military was “inextricably linked” to the United States through the support it received as part of Washington’s containment policy.

Political entrepreneurs may also find ways to link seemingly unrelated political cleavages. For instance, they can highlight the consequences of different international alignments for the regional, ethnic, or partisan distribution of domestic resources. A government’s perceived reliance on external powers may make foreign policy a rallying cry for opposition groups seeking to topple or weaken the incumbent, even if this was not previously a major political issue. Moments of crisis can yield unexpected alliances and new incentives to either play up or downplay international politics. There is a dynamic, contingent element to these politics that can create surprises.

This produces an analytical challenge: trying to assess the depth and commitment of domestic players’ political power and goals. In several Cold War cases, external policymakers fundamentally misjudged key domestic actors. For instance, the Eisenhower administration’s choice to back regional rebels in Indonesia in 1958 was driven by remarkably incorrect assessments of the power of Indonesian communists and the political position of the Indonesian military. Similarly, in the 1950s and 1960s, the United States became involved in trying to manage and manipulate domestic politics in Laos—to disastrous effect.

Sweeping generalizations about the motivations of domestic political players are untenable. Sometimes local actors play the “foreign policy card” opportunistically or have little genuine interest in the geopolitical rivalries of outside powers. Assuming that the contours of international competition can be mapped straightforwardly onto a domestic context is often profoundly misleading, ignoring what local actors value in favor of artificially assigning them labels. Sometimes, however, these actors are in fact highly motivated to pursue a twinned domestic and international agenda: Ho Chi Minh was genuinely both a nationalist and a communist, and the Khmer Rouge were deadly serious about their political project, both within Cambodia and toward Vietnam.

One useful approach to deal with this problem is to stress-test assumptions about the political goals of domestic actors and explore what implications change if different assumptions are substituted. How do assessments change if a local actors’ perceived commitments to a broader geopolitical objective tighten or loosen? What specific pieces of empirical evidence would allow a more confident adjudication of alignment preferences? Subjecting these evaluations to meaningful scrutiny and rigor can reduce the odds of deep miscalculations.

During the Cold War there was a recurring temptation for external states to intervene in foreign crises in the hope of creating or forestalling decisive shifts in domestic political power. This is a very dangerous way of approaching the questions of when and how to engage: Short time-horizons and apocalyptic thinking can easily lead to overreactions and bad judgments. The perception of crisis can lead to hasty reactions that mire outsiders in costly entanglements while further destabilizing domestic political situations.

Political order in contemporary Asia is not as tenuous or fluid as in the 1940s or 1960s, so major powers should take a longer, calmer view. Most domestic political players in the region have substantial autonomy from outside states. They are generally driven by internal concerns that are not purely reducible to, even if they intersect with, a binary China-U.S. (or sometimes India-China) choice. There certainly may be moments during which it makes sense to become deeply involved in local political maneuvering. In general, however, long time-horizons, analytical respect for the autonomy and power of local actors, and consistency in engagement are likely to be more prudent guides for foreign policy.

Studying the overlap between the global and domestic requires paying careful attention to how local actors are framing their political competition, both in specific moments and over a longer period of time. Overreacting to short-term rhetoric can lead analysts astray unless placed in a broader context: What may seem like taking a clear side in geopolitical contests may in fact be only the latest oscillation in a long pattern of shifts. Detailed local information is essential, rather than relying on hot-take headlines or geopolitical narratives that do not align with what is happening on the ground.