Green Lights and Red Lines: Responding to Iran’s Election Hacking

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: The hacking of the Trump campaign is only the latest aggressive cyber move Tehran has made in recent years. My CSIS colleague Emily Harding describes Iran’s various efforts to penetrate U.S. systems and recommends better defense and a more aggressive U.S. response to Iran’s attempts to undermine U.S. democracy.

Daniel Byman

***

The pattern is familiar: A hostile foreign power with an agenda hacks into a campaign system, steals information that could be compromising, and spreads it. Moscow hacked the Hillary Clinton campaign and leaked compromising information in 2016; now, eight years on, Iran has effectively copied the playbook. This is the new normal, but Iran’s use of the tactic is also something markedly new in its own right. After a decade conducting increasingly aggressive cyber activity, Iran has now fully emerged as a real and present cyber threat.

The Trump campaign alleged on Aug. 10 that Iran had used a sophisticated spearphish to invade its systems and steal sensitive information, most prominently a research document on the vulnerabilities of Trump’s new running mate, J.D. Vance. Within days, the FBI announced it was investigating not only this reported attack on the Trump campaign but also attacks on the Democratic campaign. Then, with blistering speed by government standards, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Administration, and the FBI put out a joint statement on Aug. 19 directly attributing the attack on the Trump campaign to Iran and stating that the U.S. intelligence community “is confident that the Iranians have through social engineering and other efforts sought access to individuals with direct access to the Presidential campaigns of both political parties.”

Iran played to its strengths in this effort. The hackers first targeted someone close to the Trump campaign—allegedly Roger Stone—and then used that trusted person’s email to send an infected message to the campaign itself. Someone in the campaign recognizes a trusted party, clicks, and Iran is in the system. This is a playbook Tehran and its affiliates have used extensively against a wide range of targets, from internal dissidents to think tanks in D.C. Tehran-affiliated actors have invested time and resources into complex social engineering attacks, in which the attackers convincingly mimic a trusted entity.

Iran emerged as a rising cyber power starting around 2012. That year, the BBC blamed Iran for disrupting its Persian language service, and an Iranian-government affiliated hacker attacked Saudi Aramco, infecting control systems and damaging 30,000 computers. Over the next decade, Iran conducted espionage via the cyber domain against targets ranging from banks to governments to the defense corporations. At times, Iranian cyberattackers’ actions were intentionally destructive, like when they attacked casinos owned by Sheldon Adelson in retaliation for the latter’s blithe suggestion that the United States nuke the Iranian desert as a negotiating tactic. Many attacks, like their November 2023 hack of water systems inside the United States, were meant to send a splashy message: We will come after those who support Israel and who defy Iran.

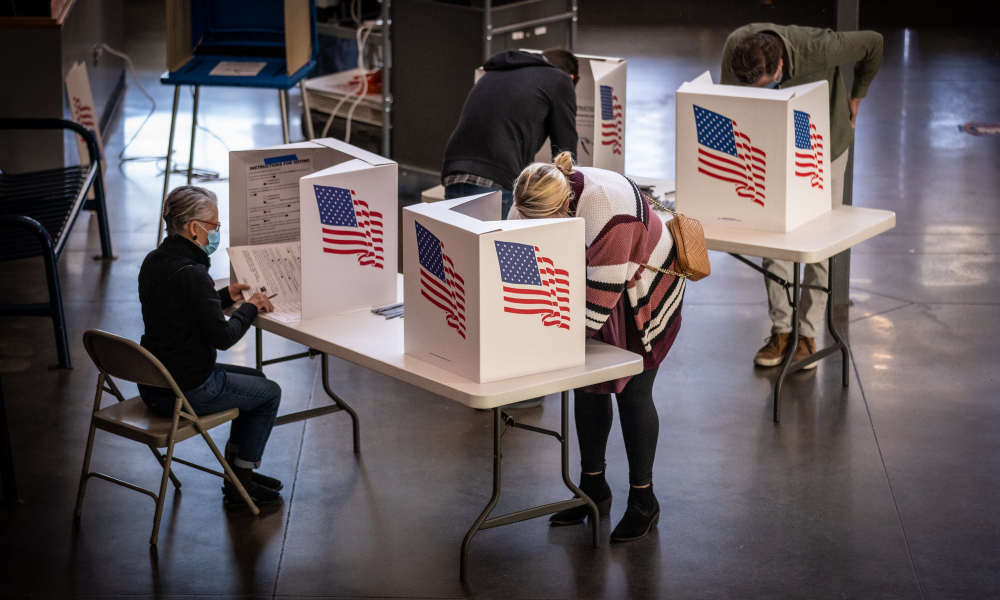

The attack on the Trump campaign is not the first time Iran has attempted to interfere in a presidential election. In 2020, Iranian-sponsored hackers compromised a state voter website. Then, posing as a far-right group, they emailed Democratic voters, threatening violence if they did not vote for Trump. They also sent Facebook messages and emails to Republican members of Congress and the Trump campaign, claiming to be volunteers for the Proud Boys. The messages claimed that Democrats were going to use “serious security vulnerabilities” in voter registration websites to “edit mail-in ballots or even register non-existent voters.” These messages included a video claiming to portray the fraudulent casting of ballots via the Federal Voting Assistance Program for military and overseas voters.

This effort was caught quickly and exposed before it could do damage. But it demonstrated both Iran’s will to undermine Americans’ faith in their election systems and also the capability to use domestic flash points, like the Proud Boys, as a wedge.

The extent of Iranian efforts for 2024 has yet to be revealed—the FBI’s investigation may take months—but the election will happen Nov. 5 no matter what. Policy cannot wait for the criminal justice system’s slow wheels to turn. Urgent action is needed.

There are two answers to the problem of a hostile power attempting to manipulate U.S. elections. The first is defense, and the steps are painfully obvious. Campaigns have to be aware of the threat and on guard for attacks. That is easier said than done: The infiltration of the Democratic National Committee in 2016 hinged on a typo in an email. The target of the spearphish, campaign chairman John Podesta, was justifiably suspicious of the email and forwarded it to information technology (IT) for closer inspection. However, along with doing the right things, like sending Podesta the right link for resetting his password and telling him to set up two-factor authentication, the IT staff made a crucial mistake. They wrote back to Podesta “this is a legitimate email” when they meant “illegitimate.” So rather than use the safe link that IT sent, Podesta clicked.

Tech companies, including Microsoft and Google, have created tools to make this job slightly easier for campaigns, providing additional protections for email accounts of likely targets. But campaigns may need to do more. If they are collecting sensitive or embarrassing information about potential candidates for high office, they may want to steal a page from the intelligence community’s book and use air gapped systems or stand-alone enclaves for sensitive documents.

The second answer is far more difficult. The current U.S. government must establish clear warnings and tangible consequences for foreign powers that attempt to interfere in U.S. elections. Policymakers who have been in discussions about how to do this know that attribution is frequently slow or low confidence, leading to hesitation rather than a quick response. Barring physical destruction from the hack, the policy default is often deescalation or symbolic punishment, which is often meted out as more sanctions on an already heavily sanctioned entity. Domestic politics are also a serious concern. The current administration does not want to be seen as interfering in the election themselves for fear of inadvertently undermining faith in elections, and this was one of the main arguments the Obama administration made in 2016 in defense of its lack of action.

All these cautions are legitimate. But doing nothing is also a policy, and in the case of election interference, it is perhaps the worst policy. Not reacting gives the adversary a green light to keep interfering. If there is no cost to the malicious activity, why not push the boundary? Since the exposure of Russia’s interference in 2016, for which it experienced few consequences, we have seen China and Iran also put a toe in those waters, and Russia has continued to swim. There is little indication this problem will simply fade. Instead, with the proliferation of artificial intelligence, more actors will be able to cheaply and effectively engage in their own efforts, and more sophisticated actors will be able to dramatically expand their reach.

The Biden administration should make clear that interference in the election is a true red line—no matter which campaign is targeted or who benefits. The Biden administration should threaten real consequences and then restore the credibility of U.S. red lines through action. The response to the Iran hack could be a true tit-for-tat: Iran just had an election, and surely the U.S. government collected sensitive information about the candidates. Declassify and release it, ensuring it lands inside Iran’s borders. Embarrassment is a far greater threat to Tehran’s closed authoritarian society than it is to Washington. Some observers may argue that now is the wrong time to push back on Iran, given the tense situation with Israel. They would be wrong. Iran must realize that the United States will not coddle and cajole it into a more responsible posture on the world stage. Especially when it comes to core national values, like a free and fair election—something Iran knows little about—U.S. resolve must be unbending and its tolerance for this sort of meddling gone.